Полная версия

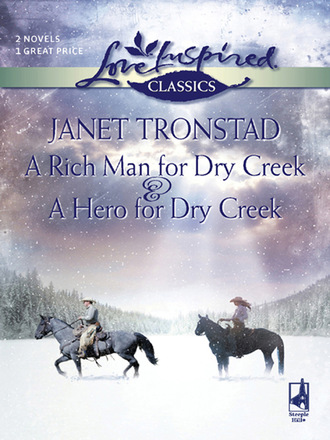

A Rich Man For Dry Creek And A Hero For Dry Creek

He walked away wearing an old pair of denim jeans and a flannel shirt. The only thing expensive about his clothes had been his tennis shoes. He had no car. No cell phone. A dozen twenty-dollar bills, but no credit cards.

He still remembered how good it felt.

That day he left behind Robert Buckwalter III and became simply Bob. He rolled the name around on his lips again. Bob. He liked the sound of it. It was friendly in a way Robert could never be.

Robert had intended to spend a week alone in the desert at some flea-bitten motel along the highway so that he could return to his parties with more enthusiasm. He certainly didn’t intend to be stuck as Bob. He was merely cleansing his palate, not giving up the rich life he enjoyed.

But that first day he discovered Bob was the kind of guy people talked to. Robert was amazed. He’d never realized until then that people didn’t talk to him; they mostly just told amusing stories and agreed with everything he said.

They were, he concluded in astonishment, handling him. How could he have not noticed?

He didn’t have friends, he realized. He had groupies.

An old man in a beat-up truck had given Robert a ride south out of Tucson and invited him to share supper. Supper had been spicy beans and warm rice with a toaster pastry for dessert. The plate he used had been an old pie tin and the glass had been a jelly jar. The fork he ate with had a tine missing.

But the whole meal had been given in kindness and it tasted very good. When it was finished, the old man offered him a job earning twenty-five dollars a day chopping wood for his winter’s supply.

Robert had been about to refuse. He had enough money in his pocket for meals and a cheap hotel. He didn’t need a charity job. But something in the man’s eyes tipped him off and instead he looked at the woodpile and saw it was empty except for a few scrub branches.

The old man couldn’t chop anymore. He needed help. Robert offered to chop some wood to repay the man for supper.

One meal led to the next and the woodpile grew. Robert’s days found a rhythm. He slept in a camper shell by one of the old sheds on the man’s property. The nights were a deep quiet and he slept more peacefully than he ever remembered.

Each morning he woke up to the disgruntled crowing of a red rooster he’d nicknamed Charlie. Charlie had no trouble making his opinions known; he had never learned to bow down to the opinions of the rich. He didn’t even respect the opinions of nature. He seemed to be particularly unhappy with the sun each morning.

Robert didn’t want to chop wood in the chill of the early morning—and especially not with Charlie strutting around. Robert had never seen anything as cranky as that red bird in the morning. You’d think the morning had come up as a personal insult to the rooster. At least Charlie took it that way.

So, instead of listening to Charlie, Robert would jog down the hard-packed dirt road for several miles. He aimed himself in the general direction of the mountains even though they were so far away he’d never get there by running. But he liked to look at them anyway.

His morning run took him past two run-down houses with an astonishing assortment of children spilling out of each. Toddlers. Teens. Boys. Girls. One morning some of the children started to follow him on his run. Before the end of the week, a dozen kids were trailing after him and he was carrying the smallest in a backpack he made from a blanket.

It took a full week for them all to tell him their names.

It was the second week before Robert noticed most of them were running in thin sandals and slippers.

Robert almost scolded them for not dressing right for running, when he realized they were wearing the only shoes they had. The next morning he brought some old newspaper with him and had the kids each make a drawing of their right foot for him.

Later that day he hitchhiked to the nearest post office and sent an overnight package to his secretary ordering fourteen pairs of designer tennis shoes just like his.

The shoes arrived on a Monday.

It was Thursday before Robert saw the children were all limping and he realized he had forgotten socks. How blind could he be? He’d realized then just how removed he’d always been from the needs of others.

He gave money, but it was other people on his staff who actually worried about the arrangements. He, himself, paid very little attention to the needs of others. His contribution was reduced to a dollar sign. It was a picture of himself that he didn’t particularly like.

Unfortunately, others still had a fascination with his wealth and the tabloids fed their interest.

Too bad he wasn’t still living in the camper shell with Charlie, Robert thought. Charlie might like being in the tabloids.

Robert had discovered he didn’t like being in tabloids. In fact, he could honestly say he hated it more than Charlie hated the morning.

Robert removed the phone from his pocket and pushed the redial button. He wondered how much it would cost to kill the story.

Not that it mattered. Whatever it was, he already knew he’d pay it.

Chapter Two

R obert Buckwalter didn’t ordinarily notice the stars in the sky. But, standing still, holding the cell phone in his right hand, he looked up and blinked. Montana had a blackness to the nights that calmed him. He’d spent too much time in cities with all their noise and lights.

All of the commotion stopped a man from thinking.

And he needed to think his way out of this situation. Money wasn’t enough this time.

Jenny’s sister had crumbled when she realized who was on the other end of the phone. Robert had not even needed to be stern. The young woman confessed why she’d called her sister and apologized for asking questions.

She was contrite. She was abashed.

She was useless.

Robert had groaned inside when he found out why the young woman had called. He had dreaded the bachelor list even before his five months in Arizona. What sane man wouldn’t?

The bachelor list winners might as well enroll in a circus freak show. No one left them an ounce of privacy. Or dignity. Last year he’d been number seventeen. Some tabloid had printed the sizes of all one hundred men’s underwear. Ten different women had actually sent him silk boxers with their names screened on them.

And the letters! He had over a hundred letters from strange women asking him to marry them.

Just imagine if he was in the number one spot. They might as well shoot him now before his mailman filed for workmen’s compensation because of the backache from delivering those letters—a fair number of which would come with a string-tied package. Somehow the packages with string on them always included baked goods. Chocolate-chip cookies. Plum bread. One enterprising woman had shipped a pot roast in a gallon-size zipper bag because some tabloid story had mentioned he liked beef.

And the underwear givers and the cookie bakers were not even the worst of the lot. The more aggressive called on the telephone and demanded to talk to him. They wouldn’t take no for an answer. They knew how to dodge every polite refusal. His secretary was likely to quit this time around.

Maybe he should hire Charlie to take those calls.

Robert, himself, wasn’t interested in a wife that came from a list.

It was old-fashioned, but Robert knew if he ever did marry it would be a real marriage. One that lasted a lifetime. Not one based on lists or money. Odd as it sounded, he’d realized in his five months away that he wanted a wife who would want a simple home with him. Without servants and expensive antiques. Someone who would want him to mow the lawn and take out the trash. Someone who would talk to him and not just quietly pretend to find whatever he was talking about fascinating enough for both of them.

A woman like that probably didn’t even read the tabloids. She certainly wouldn’t mail him a pot roast or a pair of boxers if she didn’t know him.

No, if Robert ever wanted to live a normal Bob-like life, he needed to start it now. He needed to get off the list.

The trouble was he didn’t trust the young woman he’d spoken with to simply tell her editors that Robert Buckwalter thanked them very much for thinking of him, but could they please think of someone else for their bachelor list.

Fortunately, Robert knew one thing and that was the celebrity world. He’d been forced to learn how it worked. He knew stories were killed every day and that lists could go up in smoke with the wrong move.

As Robert saw it, he had one chance to change things and that was to make himself very unpopular. He needed to do something that would alienate women everywhere. He’d asked the woman and she’d confessed that the list was to be released on February 29. Leap Year’s Day. Women’s choice. It was already February 20. He needed to act fast.

First, a victim must be found. He found that nothing set off women better than mistreatment of one of their own. And Jenny, the chef, must know about the action so she could tell her sister who would then tell her employers. That should get his name thrown off the list and into the trash.

Robert felt better already. All he had to do was be obnoxious. His feet were still sore, but he was sure he could be sufficiently unpleasant to raise some eyebrows.

Confident that his troubles would soon be over, Robert slipped the cell phone back into the pocket of his overcoat and started to whistle.

He was almost cheerful when he stepped back into the kitchen. It wouldn’t be too hard. Before long his reputation would be back where it belonged—in tatters.

All he needed to do was find a woman to persecute.

Robert stepped into the kitchen to find it empty of everything except steam. He walked over to the stove and looked into one of the big lobster pots. It was empty, as well.

Good, he thought to himself in satisfaction, the party was starting. An audience would be helpful for what he needed to do.

The dining room of the café had been turned into a girl’s dressing room and Robert walked quickly through the haze of perfume. Makeup was scattered over the table closest to the door and several pairs of high heels were lined up along the right wall.

Robert stopped in front of the mirror taped to the inside of the door and ran a comb through his own hair. He brushed a few snowflakes off the shoulders of his overcoat. The overcoat was black. His suit underneath was black. Each cost more than most men made in a month.

Robert nodded at his reflection with satisfaction; he looked good. Every man should look good on his way to his own public scandal.

The first bite of the cold when he stepped out the front door made him step even faster. The café was just down the gravel road from the barn where the party was to be held and the space between was full of old cars and trucks. This part of Montana certainly wasn’t prosperous, he thought as he spied the old cattle truck that was parked next to the bus his mother had rented to haul all the teenagers around.

He nodded to an old man who was weaving between the cars with a bottle of beer in his hand.

“Coming to the party?” Robert looked closer at the man.

“Ain’t been invited.” The man’s beaten face looked anxious in the moonlight.

“Everyone’s invited,” Robert said firmly. The old man looked like he could use a good meal that didn’t slide down from the neck of a brown bottle. “What’s your name?”

The old man looked startled. Robert didn’t blame him. He was startled himself. Since when had he cared about the names of poor old men?

“Gossett.”

“Well, Mr. Gossett, I hope you’ll come have some dinner with us.”

“I ain’t dressed for it.”

The man was wearing a beige cardigan sweater covered with what looked like cat hair and a thermal undershirt that had a yellow ring around the band. His neck was scrawny and his eyes were bloodshot. His denim jeans had grease stains on the knees. Only the man’s boots looked new.

“This will set you up,” Robert said as he took off his overcoat and offered it to the old man. “Put that on and you’ll be right in fashion.”

Warm, too, Robert thought to himself.

The man’s startled look turned to alarm. “You with the Feds?”

“The who?”

“The FBI. They don’t think I seen them. But they’re here. Sneaking around in the dark. Watching me.”

“They’re not watching you,” Robert said gently as he offered the coat again. “I’ve heard there’s been some cattle rustling reported. Interstate stuff. It’s been going on for some time and they can’t get a handle on it. That’s why they’re here. It’s just the cattle. It’s nothing for you to worry about.”

Robert knew the FBI was in Dry Creek. One of their agents had questioned Jenny and himself when they’d landed with the lobsters out near Garth Elkton’s ranch the other night.

“You know who they think done it?” the man asked, leaning so close that Robert got a strong whiff of alcohol. “The rustling?”

“No, I don’t think they know yet.” Robert wondered if he should insist the man come into the warmth of the barn. With the amount of alcohol the man was drinking, it was dangerous for him to be out in the freezing temperatures. “You’re sure you don’t want to borrow the coat? You’d be welcome to eat with us.”

The man carefully set his bottle of beer on the hood of an old car before reaching out toward the coat. “I might just get me a little bit of something. It sure smells good.”

The two men walked inside the barn together.

The old man headed toward the table set up with appetizers. Robert resisted the urge to go over and visit his carrot flowers. Instead he looked around for the woman he needed.

There was a sea of taffeta and silk. Young teenage girls with heavy lipstick and strappy high heels. Farm wives with sweaters over their simple long dresses. A couple of women who looked unattached.

And, of course, the chef.

If he had his choice, Robert would persecute the chef. If for no other reason than to rattle her calm and make her take off that hairnet of hers. It was a party. She could loosen up. But the only thing he could think to do was to kiss her, and that certainly wasn’t outrageous. The media would just think he’d taken another in a long line of girlfriends. They’d yawn in his face.

No, he needed something shocking.

He looked over the teenagers and settled on the youngest one. His kissing her would raise the hackles of the tabloid world. She looked to be little more than a child, no more than twelve. Women all across the country would raise their handbags in unison to clip him a good one and he’d deserve it.

Robert went over to the buffet table. He’d look less threatening if he had one of those plastic cups in his hand. After all, he wanted to kiss the girl, not have her pass out in terror. She might be wearing lipstick, but twelve was still awfully young.

He nodded to the older woman behind the table. “I’ll have some champagne.”

The woman looked at him blankly. “I think there’s punch in the bowl.”

Robert looked over and saw the punch. It was pink.

“I don’t suppose there’s any bottled water?”

The woman shook her head no. “There might be coffee later.”

Robert nodded. He’d have to do this empty-handed. He walked over to the girl. She was leaning against the side of the barn and watching the other kids sort through some old records. Now who had those relics? He couldn’t remember ever seeing records played. Not with cassettes and CDs available.

“Know any musicians?”

The girl looked up and shook her head shyly. “Do you?”

Robert nodded. He’d be able to score a few points with this one. “Name a group and I probably know them.”

He realized when he said it that it was true. The world of the truly famous was pathetically small.

“Elvis,” the girl named softly.

“Elvis is dead.”

“I thought maybe you had known him. When you were young.”

Robert wondered if he’d fallen down a time warp. “How old do you think I am?”

The girl shrugged. “He’s my favorite is all.”

“He’ll always be the King,” Robert agreed gently. Maybe this girl wasn’t the one, after all. Her eyes reminded him of Bambi. He didn’t want to see the confusion in them that would surely come if a man as old as Elvis kissed her.

“You got a camera?” he asked instead.

“A disposable one.”

“Do me a favor and take a few pictures of me tonight. I’ll tell you when.”

“Sure.”

Robert nodded his thanks. Tabloids loved pictures like that and even sweet-eyed Bambis needed a college fund. Somebody might as well get some good out of tonight.

The lights in the barn were subdued and the whole place seemed to smell of butter and steam. Long tables were set up in the back of the barn and covered with white cotton tablecloths. Stacks of heavy plates, the kind found in truck stops, stood at the end of each table.

Several teams of ranch hands were holding big trays with a towel draped over steaming lobsters. Robert frowned at the men. Why hadn’t Jenny asked him to help? He’d had to practically demand a knife and some carrots earlier.

Jenny put a dozen silver tongs down on the head table and blessed Mrs. Buckwalter for requesting that they be brought to Dry Creek along with dozens of tiny silver lobster picks. Even Jenny wasn’t sure she’d tackle the lobster dinner with plastic forks and no tongs. “Can someone go back and get the last pan of butter?”

“I’ll do it.”

Jenny stopped arranging the tongs and looked up in panic. It was Robert Buckwalter. “But you can’t—I mean you don’t need to—”

“Well, someone needs to.”

“I can do it myself,” Jenny said. She could at least try to remember the difference in their social standing. He was, after all, her employer’s son. “You don’t want to spill butter on that suit. It looks expensive.” Jenny took a deep breath and smiled. Her sister owed her for this one. “I mean, it’s a tuxedo, isn’t it? Good enough to wear to a wedding.”

“Tonight’s a special occasion.”

“Aren’t they all?” She struggled upstream. “These receptions—nothing brings out the good suits like a reception or a wedding.”

Robert nodded. “Or a funeral.”

Jenny started to sweat. Being a news source was more difficult than one would think. “Funerals and weddings. Sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference.”

Robert looked at her like she’d lost her mind.

“I mean sometimes weddings get off to a rocky start.” Boy, did her sister owe her.

Robert nodded. “I suppose so.”

“Been to any weddings lately?”

Robert shrugged. “Not for a while. I’ve been away from the social scene.”

“Oh?” Jenny looked up brightly. Now they were getting somewhere.

“Haven’t missed it.” Robert looked toward the barn door. “It won’t take me a minute to run back to the café and get that butter.”

Jenny nodded in defeat. “It’s on the back of the stove. Be sure and use a pot holder.” She suddenly remembered to whom she was talking. “That’s a padded square of cloth. It’ll be on the counter.”

“I know what a pot holder is.” Robert didn’t add that he hadn’t known until five months ago.

Jenny stood with her back to the tables and watched Robert walk out of the barn. He was limping. Now she wondered why a man who had spent five months resting would be limping.

“Handsome, isn’t he?”

Jenny turned to look at the woman standing next to her. Mrs. Hargrove was one of the people in Dry Creek that Jenny liked the best. She’d organized the apron brigade for Jenny, using aprons from the church. Towel aprons. Frilly aprons. Patched aprons. They’d used them all.

“You’re pretty good-looking yourself,” Jenny said.

The older woman had worn a gingham cotton dress every other time Jenny had seen her. Tonight she was in a silk mauve dress with a strand of pearls around her neck. A lemon scent floated around her.

“Maybe he’ll ask you to dance,” Jenny continued. Mrs. Hargrove had said earlier that this was the first dance she’d attended since her husband died two years ago.

“Me?” Mrs. Hargrove laughed. “I was thinking he’d ask you to dance.”

“No time. I’ll be busy with the food.”

“Not when the dancing starts.”

“No, by then I’ll be busy with the pots and pans—washing dishes.”

“Goodness, no! The dishes can wait. Tomorrow’s soon enough for that. We’ll all pitch in then. That’s the way it’s done here. I might even ask old man Gossett to help us. Be good for him to get out. You’d be doing him a favor.”

Jenny had a sudden wish that she could dance. “But I’m not dressed for a party.”

Mrs. Hargrove shrugged. “I’ll bet there’s a few more dresses at the café.”

The women of Dry Creek had loaned their old prom dresses and bridesmaids dresses to the teenage girls from Seattle. For most of the girls, this was the first time in their lives they had worn a formal dress.

“He’s back,” the older woman announced.

Robert Buckwalter entered the barn doorway and stood for a moment. Jenny could see the blackness of the outside air. Snowflakes were scattered on his head and shoulders. His hands were carefully wrapped around the handle of the saucepan he was holding. He hesitated in the doorway as though he was shy, unsure of his place among the guests. His shyness, combined with the perfect balance of his face almost took her breath away. Maybe he did deserve to be the number one bachelor.

He certainly didn’t deserve to carry the butter.

“Here, let me get that.” Jenny wiped her hands on her apron and started toward him. The steam from the lobsters had made her hands clammy. “You shouldn’t have to—”

“I can carry a pan of butter.”

“Of course.” Jenny stopped. Of course he could. Why in the world was she so nervous around the man? It must be her sister. Making him sound so mysterious. Just because he was rich, it didn’t mean he wasn’t just a regular kind of a guy, too. He just had more change in his pockets than most.

“Dinner’s almost ready.” Jenny turned to talk again with Mrs. Hargrove.

The regular guy walked around her toward the table.

“Then your troubles for the evening will be over,” Mrs. Hargrove said kindly as she put a hand on Jenny’s arm. “We’re so grateful for all the work you’ve done, dear.”

Robert frowned as he set the saucepan on the table. If dinner was coming soon, he had work to do fast. He suspected people were always more easily shocked on an empty stomach. Plus, after dinner, the sounds of those records playing would mask his attempts at being outrageous.

He’d given some thought to his dilemma while outside and he’d decided age could go two ways. Instead of focusing on someone young like Bambi, he could try someone old enough to be his grandmother.

“Ah, there you are.” Robert turned back to Mrs. Hargrove. He understood she was the Sunday school teacher for most of the little people in Dry Creek. She should be thoroughly offended by a kiss from a strange man. Everyone else should be shocked, too.

He looked around for Bambi and called her over. There’d be no point in rattling the people of Dry Creek if he couldn’t shake up the rest of the country, too.

“Yes?” Mrs. Hargrove looked up at him. Her eyes were bright with curiosity. Her cheeks were pink. She must be seventy years old. She looked like every cookie-lover’s picture of Grandma.

Robert dove right in. “I love you.”

“Why, I love you, too.” She beamed back.

“What?” Robert stalled. This wasn’t the way it was supposed to go.

“I love all of God’s children,” Mrs. Hargrove continued. “They say that’s how Christians will know each other. By the love they have for others. I John 4:7. Does this mean you’re a Christian?”

“Well, no, I—I mean I’m not opposed to Christianity.” Robert started to sweat in earnest. How had God gotten into this? “Don’t really even know much about it—”