Полная версия

The Giver von Lois Lowry. Textanalyse und Interpretation. Königs Erläuterungen Spezial

The 1990s saw in SF as well as in most other genres of pop culture media an increased presence of women working in fields which had usually been associated with men. While there had always been women writers of science fiction, including some of the most admired and respected writers in the field (notably Octavia Butler 1947–2006 and Ursula LeGuin 1929–2018), and the creator of the genre was a woman (Mary Shelley, with Frankenstein in 1818), the genre of science fiction has always been widely viewed as something by and for boys. During the 1990s this changed dramatically.

Lois Lowry’s venture into science fiction came in the early 1990s: she had never written in the genre before. Her approach to science fiction is not particularly true to the genre, and it is only when she began to expand on the world of The Giver with the sequels, years later, that she seems to have concentrated more and put more thought into the structures and systems of her imagined future world.

But her novel arrived at a time when young adults – teenagers – were being increasingly discovered and targeted as customers and readers. So The Giver could be marketed and sold as a children’s book, or, as they were then becoming known, as YA fiction, rather than as science fiction.

The processes of hybridisation which were changing pop music and mainstream cinema were having a different effect in the world of literature. Books were being marketed in an increasingly sophisticated way, echoing the traditional marketing of pop music for particular audiences (the most important American music charts, for example, have long been subdivided into categories like “rock”, “country” and “R&B”, targeting the different relevant audiences specifically).

The pressure for publishers and booksellers to market new books to existing target audiences has always resulted in a large amount of generic fiction – books which are written to fulfil existing expectations on the part of the reader. Many of the YA dystopian fantasies which have appeared since the huge success of Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games (2008–2010) have been little more than attempts to sell as similar a story as possible to the same readers, for example, and J. R. R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (1937–1949) created an entire genre, with literally hundreds of authors in the years since working in exactly the same style and using exactly the same themes and storylines.

Lowry’s The Giver is an unusual example of a book which has ancestors – Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) is an obvious one – without being an attempt to reproduce or imitate, and which has been both critically acclaimed and wildly popular, and yet has not produced imitations. Its contemporary background is interesting but actually less relevant to the book itself than is frequently the case, in particular for dystopias or SF, both being genres which by their very nature often tend to reflect on the environment in which they were created. As she explains in her Newbery Medal acceptance speech in 1994, the roots of The Giver go much further back than the contemporary world in which she wrote it – 1990s America – into her childhood in Japan and through the 1950s and 1970s[3]. The success of The Giver can be attributed in part to increasingly sophisticated marketing processes which allowed it to benefit from the growing exploitation of the YA fiction target audience, but its enduring power and success have to do with the fact that it is a book rooted in a much deeper past than the USA of the 1990s.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

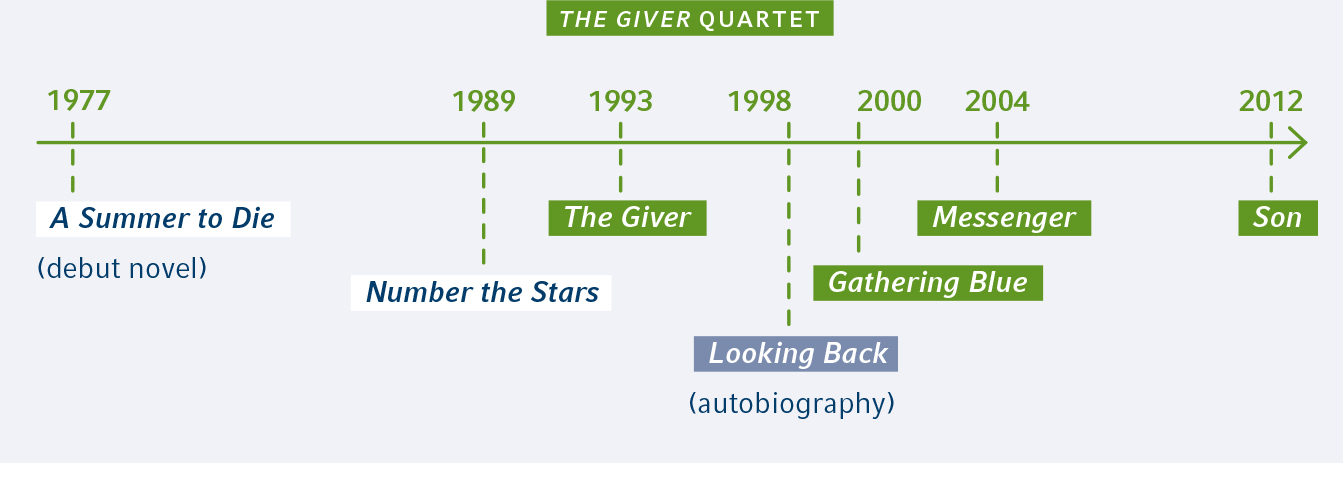

Lowry has written more than 40 books for children and young adults. She has won and been nominated for many prizes for her work, including the most prestigious awards in the field of children’s literature, including the Hans Christian Andersen Award and the Newbery Medal (twice). Her most famous, popular and acclaimed books are The Giver (1993) and Number the Stars (1989).

Many of her books have been multi-volume series, like The Giver, which became a quartet, and the Anastasia series for younger readers, with nine books written between 1979 and 1995. She has also written several stand-alones and an autobiography. Her most recent book was Gooney Bird and all her Charms (2014), the sixth title in the Gooney Bird series for younger readers.

Lois Lowry has written too many books to present them all in this study guide, but here is an overview of a few of her most important published titles.

The Giver Quartet

Lowry says of the “sequel” to The Giver that she imagined a world “of the future […] one that had regressed instead of leaping forward technologically as the world of The Giver has”[4]. All of the books are set in the same world, but each one has a different protagonist.

She has often been asked why she waited so long – or why it took so long – to continue the story begun in The Giver. In her Newbery Medal acceptance speech she uses the metaphor of a river and its tributary streams to describe the accumulation of ideas and inspirations for a story[5]. When asked about the last book in The Giver quartet, she uses a cooking metaphor:

”I very often have things brewing for a long time... It’s as if on another stove somewhere, in another house, a soup or a stew is cooking, and from time to time I tend to it and toss in a different herb or sprinkle some pepper into the pot and let it return to its simmer. The book that is now called Son (for years it had no title) was like that. It was there, it was Gabe’s story, it was started, and it needed time to simmer.”[6]

Gathering Blue (2000)

Kira is a girl born with a deformed leg. The society she lives in gets rid of its weak or disabled members. Normally she would have been sent to the Field, where she would have become a victim of The Beasts, but she has a talent for embroidery and begins to learn the art of dyeing colours. The only colour no one knows how to make is blue, which has been lost. She learns more about the secrets of the world around her (like Jonas in The Giver). The end of the book includes hints that a boy from another community has blue eyes (an implied reference to Jonas).

Messenger (2004)

This book follows the story of a character from Gathering Blue called Matt (or Matty) who is a Messenger, carrying news and messages between settlements. He is a friend of Kira’s in the earlier book. In Messenger we learn that Jonas has survived and is Leader of a community, and that Gabe is also still alive. It is set roughly eight years after the events of The Giver.

Son (2012)

When asked why she decided to write Son, Lois Lowry said that it was because so many readers had asked her what had become of Gabe, the baby from The Giver[7]. So Son is about Gabe, although the larger part of the book is mostly about his Birthmother Claire. The story is told in three parts, ‘Before’, ‘Between’ and ‘Beyond’, covering the time from Claire’s pregnancy with Gabe (who is actually called Thirty Six) at the age of 14 to Gabe as a young man, with special powers, who must defeat an evil force (the Trademaster) to save his mother.

Other titles

Autobiography: Looking Back (1998); revised and expanded 2016

A Summer to Die (1977): This debut novel was obviously a very personal and intimate project for Lowry. It was her first published novel, and was inspired by the death from cancer of her elder sister at the age of 28. The story is similar: the protagonist, Meg, is the younger sister of Molly, who dies of leukaemia. The book is about families, grief, and how to find love and comfort in loss and suffering.

Number the Stars (1989): Next to The Giver, this is probably Lowry’s most famous and acclaimed book. Told from the perspective of a teenage girl, it is an historical YA novel about the escape of a Jewish family from Copenhagen, Denmark, during the Nazi occupation in World War 2. It was the first of Lowry’s books to win the prestigious Newbery Medal (the other being The Giver). The title is a reference to Psalm 147 in the Bible[8]. It remains one of the bestselling children’s books of all time[9]. It was widely praised by critics and has been adapted for the stage several times. A film production is also planned.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Lowry’s inspirations and sources for The Giver were her own memories and her thoughts about how memory works. The other major themes of conflict and individualism are also drawn from her own experience and thoughts about life. In her 1994 Newbery Medal acceptance speech, Lowry gave an unusually detailed and thoughtful account of the accumulated inspirations and origins of the book.

In her acceptance speech when she was awarded the Newbery Medal[10] for the second time in 1994, Lois Lowry spoke in detail about things from her own life which had influenced The Giver. She uses a river as a metaphor for a life, for the accumulation of memories and influences, and for the idea of the past and the passage of time itself. She quotes from The Giver, a scene where Jonas looks at a river and “the history it contained … there was an Elsewhere from which it came, and an Elsewhere to which it was going”[11]. She then uses this idea of “Jonas looking into the river and realizing that it carries with it everything that has come from an Elsewhere” as an expression of “the origins of this book”. Staying with the river metaphor, Lowry says that the individual memories she is about to discuss are like tributaries (small streams which flow into a river to increase it in size) which have contributed not only to the river of her life, but to the river which was the creative process which became/gave birth to The Giver.

It is relatively unusual for a writer to talk so openly and in such detail about the specific events, feelings and situations which contributed to creating something. This is not just because of shyness or a desire for privacy or wanting to cultivate an aura of mystery: it is probably very often also just because a lot of writers aren’t able to precisely identify where and how their ideas developed and grew, and what the original seeds of an idea actually were. Lowry’s Newbery Medal acceptance speech is therefore an interesting and rare example of a writer talking very openly and in great detail about the specific details of how an idea grew over the years to become a novel.

Pay attention to the repeated mantra of “comfortable, familiar, safe” throughout the speech: this is something Lois Lowry has identified as a common thread throughout all these memories, and which is one key to The Giver.

These are the memories and inspirations Lois Lory talks about in her 1994 acceptance speech:

When she was 11 years old in 1948, Lois moved with her family to Tokyo in Japan. They lived in an entirely American environment. Later as an adult she asked her mother why they hadn’t tried to interact more with Japanese people and learn more about the culture and the country, and her mother is surprised. “She said that we lived where we did because it was comfortable. It was familiar. It was safe.” Driven by curiosity, 11-year old Lois rode her bike out of the American area into another part of Tokyo, where she was overwhelmed by the sensory input from what was an entirely new and alien world for her, with all the different smells, sights, colours, sounds and different impressions of a foreign culture. As a girl, Lois would often leave the American area to walk around and soak up the culture and the different environment. Though she rarely has contact with people during her short trips through Tokyo, until one time a woman touches her hair and says something which Lois as a child misunderstands to mean “I don’t like you”, but which she later realises was actually a compliment on her hair, saying “it’s pretty”. Lowry says that this moment of miscommunication was an extremely important memory for her. She says: “Perhaps this is where the river starts”, meaning that in her use of the river as a metaphor for her life and the origins of The Giver, this could be the oldest memory which eventually led to the book being written.

In the mid-1950s Lois is at college. She remembers how she and the other girls in the dorm (shared student accommodation) were all basically alike – they dressed and behaved the same, they had the same habits and routines and style. One girl was different, however, “somehow alien, and that makes us uncomfortable”. Lois and her friends are unsure how to deal with someone who is different, so “we react with a kind of mindless cruelty … we ignore her. We pretend that she doesn’t exist. … Somehow, by shutting her out, we make ourselves feel comfortable, familiar, safe.” She describes this memory, which returns to her again and again over the years and which is “profoundly remorseful”, as being another tributary entering the growing river.

The face of the painter on the cover of the US anniversary edition.

© Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

In 1979 Lois is working as a journalist and is sent to write an article about a painter who lives on a remote island off the coast of Maine. In talking to the painter she learns that his capacity for seeing colour is much greater than her own. She takes a photograph of him which she keeps above her desk. Years later she learns that he has gone blind. She wishes at times “that he could have somehow magically given me the capacity to see the way he did”. This is evidently a key moment in the development of the idea which became The Giver.

In 1989 she goes to Germany because one of her sons is getting married there. The ceremony is in German, which she doesn’t understand, but one section is in English, and she reflects on how “we are all each other’s people now”. The sense of community and oneness, Sameness, even, is present here in this memory: “Can you feel that this memory, too, is a stream that is now entering the river?”

Later, her father is in his late 80s and in a nursing home. He is surrounded by photographs of his family, and at one point he points to Lois’ older sister Helen, who had died very young of cancer, and says that he can’t remember what happened to her. “We can forget pain, I think. And it is comfortable to do so. But I also wonder briefly: is it safe to do that, to forget? That uncertainty pours itself into the river of thoughts which will become the book.”

In 1991 she is giving a talk about her book Number the Stars (about the Holocaust) and a woman in the audience asks her “Why do we have to tell this Holocaust thing over and over? Is it really necessary?” She replies to the woman by quoting her German daughter-in-law, who says: “No one knows better than we Germans that we must tell this again and again.” But later, Lowry says, she played Devil’s advocate by asking herself; wouldn’t it actually be “a more comfortable world” if the Holocaust was forgotten? “And I remember once again how comfortable, familiar and safe my parents had sought to make my childhood by shielding me from ELSEWHERE. But I remember, too, that my response had been to open the gate again and again.” This is another key to the growth of the story and themes of The Giver.

The next memory is of her having lunch with her daughter in a pub. A news story comes on the TV about a mass shooting incident having just occurred: when she hears that it’s in another state, far away from where they’re sitting, she’s relieved. Her daughter is shocked by her reaction. “How comfortable I made myself feel for a moment, by reducing my own realm of caring to my own familiar neighbourhood. How safe I deluded myself into feeling.” This is another important tributary to the river, which is “turbulent by now, and clogged with memories and thoughts and ideas that begin to mesh and intertwine. The river begins to seek a place to spill over.”

These are the memories that Lowry identified as having contributed to the creation of the book. It is worth remembering that for most of the time period covered here, with the exception of her childhood, she was working as a professional writer: she was writing and publishing stories the whole time, and while doing so, over many, many years, this one story was growing and becoming more complex and full in the back of her mind.

We can see here how she has arrived at the heart of the book, the whole point about the dangers of Sameness and Jonas’s understanding that denying negatives automatically means denying positives – no rain, no sun, no grief, no joy.

The next point Lois Lowry makes is about the ambiguous ending to the book. Remember that this speech was given years before she started writing the sequels to The Giver, which necessarily push the ending of the book in one firm direction. She mentions several different interpretations of the ending which readers had told her about. She says that some have seen it as being a “circular journey. The truth that we go out and come back, and that what we have come back to is changed, and so are we. Perhaps I have been travelling in a circle too”.[12]

She then talks about what her circular journey has been. She says “Here are the things I’ve come back to”, and lists:

Her daughter, who had been so horrified by her reaction to the mass shooting, was the first person to read the manuscript of The Giver.

The “different” girl from college is happily living with another woman now.

Her son and German daughter-in-law now have a daughter, “who will be the receiver of all of their memories”.

The photograph she took of the old painter she interviewed who went blind was used as the cover for the first edition of the book in the USA (see p. 26).

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

The Giver is organised in 23 numbered chapters. The book is short, so the chapters are also quite compact. Here is a brief synopsis of the major events and developments in each chapter, with the page number of the beginning of the chapter provided.

The first seven chapters can be treated as a kind of introduction to this strange world.

The plot begins in chapter eight, when Jonas is selected as the new Receiver of Memory.

We will look more at the structure and organisation of the narrative of The Giver in the chapter in this study guide on 3.3 Structure (p. 42).

1 (p. 9)

Jonas is nearly 12 years old. He is returning home on his bicycle. At home he has dinner with his family (parents and younger sister Lily) and they go through a ritual of talking in turn about their feelings. He is feeling apprehensive about the approaching Ceremony of Twelve.

2 (p. 16)

At dinner, Jonas’ father reminisces about his own childhood and tells Jonas what he can expect from the coming Ceremony of Twelve.

3 (p. 23)

Jonas’ father brings a baby home to care for, one with pale eyes like Jonas. Lily is excited and talks about potential Assignments. Jonas recalls an incident at school where he had been publicly shamed for taking an apple, and thinks about why the apple had caught his attention: he had seen it change in some way he can’t describe while he and Asher had been tossing it back and forth.

4 (p. 28)

Jonas goes to do his volunteer work, and looks for his friend Asher. He finds him working at the House of the Old. Jonas, Asher and another Eleven called Fiona are helping to care for the elderly (“the Old”). The woman Jonas is helping, called Larissa, tells him about a release they had celebrated that morning.

5 (p. 34)

The family’s morning begins with the ritual of Dream-telling, and Jonas tells his family about a vaguely disturbing dream he had had about the girl Fiona. The dream has sexual connotations, with Jonas’ strongest impression being “wanting” (p. 35) the girl, and he doesn’t understand this and feels awkward and uncomfortable. Jonas’ parents tell him he has experienced “the Stirrings” (first sexual feelings of desire). The Stirrings must be reported – which he has done – and treated with pills. His mother gives him a pill and tells him he will now be taking them for the rest of his life. Jonas is on the one hand proud to now be taking the pills like everyone else above a certain age, but he also in a way misses the warm and exciting feelings of sexual desire which he had briefly experienced in his dream.

6 (p. 38)

This important chapter contains a lot of useful information about the rituals, terminology and structures of the community, in particular the way in which family units are organised and children are integrated at the different stages of their lives into the community.

On the first day of the Ceremony the entire community attends the rituals of the children, from newborns being assigned to their new family units through to children aged eight getting their new jackets.

The second day includes the Ceremony of Twelve, which Jonas will participate in. He is nervous beforehand and waits impatiently through the Ceremonies of ages Nine to Eleven. He and Asher talk briefly about a story of a man who didn’t like his Assignment and left to join another community: Asher says he asked to go Elsewhere and was released.

7 (p. 45)

At the Ceremony of Twelves, Jonas is number 19 in the line and waits while the other Elevens are given their Assignments. His friend Asher is assigned Assistant Director of Recreation. Fiona is one place ahead of Jonas and is assigned Caretaker of the Old, which Jonas had expected. But instead of 19, the Chief Elder then calls up number 20, and Jonas is left sitting alone without being called for an Assignment.

8 (p. 51)

Jonas is embarrassed and frightened and the rest of the community is confused by what has happened. The Chief Elder apologises to everyone, including Jonas, and then says that he has not been Assigned, he has been selected – to become the next Receiver of Memory. She says that the Elders have been watching Jonas with this goal in mind for years now, and that the last potential Receiver turned out to be something of a disaster. She lists the qualities that a Receiver must possess, and which they see in Jonas, as intelligence, integrity, courage and wisdom – and a fifth quality, which is only called the Capacity to See Beyond.

Jonas is unnerved and wants to tell them they made a mistake, but when he looks at the community he again has the sensation he had as a child with the apple (see pp. 25–26), and he feels things change.

9 (p. 56)

Jonas notices that people treat him slightly differently afterwards. His parents are uncomfortable when he asks them what happened with the last person to be selected as Receiver, and what went wrong.

Like everyone else in the Ceremony, Jonas has been given instructions for his new role in the community: but he has a list of eight instructions which will immediately change his life. Some of his instructions directly contradict everything he has been taught, such as number 8, “You may lie”. This instruction, more than the others, disturbs him.