полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 370, May 16, 1829

A taste for figs marked the progress of refinement in the Roman empire. In Cato's time, but six sorts of figs were known; in Pliny's, twenty-nine. The sexual system of plants, seems first to have been observed in the fig tree; whose artificial impregnation is taught by Pliny, under the name of caprification.

In modern times, the esteem for figs has been still more widely diffused.

When Charles the Fifth visited Holland, in 1540, a Dutch merchant sent him a plate of figs, as the greatest delicacy which Ziriksee could offer.

H.B.AALNWICK FREEMEN

Alnwick, in Northumberland, is remarkable for the peculiar manner of making freemen. Those to be made free, or as the saying is, to leap well, assemble in the market place early on St. Mark's day on horseback, with every man a sword by his side, dressed in white, all with white night caps, attended by four chamberlains mounted and armed in the same manner. Hence they proceed with music to a large, dirty pool, called Freeman's Well, where they dismount, and draw up in a body, and then rush through the mud as fast as they can. As the water is generally very foul, they come out in a dirty condition; but after taking a dram, they put on dry clothes, remount their horses, and ride full gallop round the confines of the town, when they return, sword in hand, and are met by women decorated with ribands, bells, &c. ringing and dancing. These are called timber vasts. The houses of the new freemen are, on this day, distinguished by a holly bush, as a signal for their friends to assemble and make merry.

This ridiculous ceremony is attributed to King John, who being mired in the well, as a punishment for not mending the road, made the above custom a part of the charter of the town.

H.B.ATHE ANECDOTE GALLERY

DOCTOR PARR

How many a fine mind has been lost to mankind by the want of some propitious accident, to lead it to a proper channel; to prevent its current from "turning awry and losing the name of action!" We know not whether the story of Newton's apple be true, but it may serve for an illustration, and if that apple had not fallen, where would have been his Principia? If the Lady Egerton had not missed her way in a wood, Milton might have spent the time in which he wrote "Comus," in writing "Accidence of Grammar;" and if Ellwood, the quaker, had not asked him what he could say on "Paradise Regained," that beautiful poem (so greatly underrated) would have been lost to us.

Samuel Parr was born at Harrow-on-the-Hill, June 15 (o.s.) 1747. He was the son of Samuel Parr, a surgeon and apothecary of that place, and through him immediately descended from several considerable scholars, and remotely (as one of his biographers, Mr. Field, asserts) from Sir W. Parr, who lived in the reign of Edward IV., and whose granddaughter was Queen Catharine Parr, of famous memory. It does not appear from Parr's writings (as far as we remember) that he laid claim to this high ancestry; yet the name of Catharine, which he gave to one of his daughters, may be imagined to imply as much. His mother, whose maiden name was Mignard, was of the family of the celebrated painter. It was the accident of Parr's birthplace that, probably, laid the foundation of his fame, for to the school of his native village, then one of the most flourishing in England, he was sent in his sixth year; whilst, under other circumstances, it is likely that he would have been condemned to an ordinary education and his father's business. So many seeds is Nature constantly and secretly scattering, in order that one may fall upon a spot that shall foster it into a a plant. In his boyhood, he is described by his sister, Mrs. Bowyear, as studious after his kind, delighting in Mother Goose and the Seven Champions, and not partaking much in the sports usual to such an age. He had a very early inclination for the church, and the elements of that taste for ecclesiastical pomp, which distinguished him in after life, appeared when he was not more than nine or ten years old. He would put on one of his father's shirts for a surplice, (till Mr. Sanders, the vicar, supplied him, as Hannah did his namesake, with a little gown and cassock;) he would then read the church service to his sister and cousins, after they had been duly summoned by a bell tied to the banisters; preach them a sermon, which his congregation was apt to think, in those days, somewhat of the longest; and even, in spite of his father's remonstrances, would bury a bird or a kitten (Parr had always a great fondness for animals) with the rites of Christian burial. Samuel was his mother's darling; she indulged all his whims, consulted his appetite, and provided hot suppers for him almost from his cradle. He was her only son, and was at this time very fair and well-favoured. Providence, however, foreseeing that at all events vanity was to be a large ingredient in Parr's composition, sent him, in its mercy, a fit of small-pox; and, with the same intent, perhaps, deprived him of a parent, who was killing her son's character by kindness. Parr never was a boy, says, somewhere, his friend and school-fellow, Dr. Bennet. When he was about nine years old, Dr. Allen saw him sitting on the churchyard gate at Harrow, with great gravity, whilst his school-fellows were all at play. "Sam. why don't you play with the others?" cried Allen. "Do not you know, sir," said he, with vast solemnity, "that I am to be a parson?" And Parr himself used to tell of Sir W. Jones, another of his school-fellows, that as they were one day walking together near Harrow, Jones suddenly stopped short, and, looking hard at him, cried out, "Parr, if you should have the good luck to live forty years, you may stand a chance of overtaking your face." Between Bennet, Parr, and Jones, the closest intimacy was formed; and though occasionally tried, it continued to the last. Sir W. Jones, indeed, was soon carried, by the tide of events, far away from the other two, and Dr. Bennet quickly shot a-head of poor Parr in the race of life, and rose to the Irish bench.

These three challenged one another to trials of skill in the imitation of popular authors—they wrote and acted a play together—they got up mock councils, and harangues, and combats, after the manner of the classical heroes of antiquity, and under their names—till, at the age of fourteen, Parr being now at the head of the school, was removed from it and placed in his father's shop.

The doctor must have found in the course of his practice, that there are some pills which will not go down—and this was one. Parr began to criticize the Latin of his father's prescriptions, instead of "making the mixture;" and was not prepared for that kind of Greek with which old Fuller's doctor was imbued, who, on being asked why it was called a Hectic fever, "Because," saith he, "of an hecking cough which ever attendeth that disease." Accordingly, Parr having in vain tried to reconcile himself to the "uttering of mortal drugs" for three years, was at length suffered to follow his own devices, and in 1765, was admitted of Emmanuel College, Cambridge. Dr. Farmer was at that time tutor. Of this proficient in black letter (he was one of the earliest, and perhaps the cleverest, of his tribe) we are told by Archdeacon Butler, in a note, that he was a man of such singular indolence, as to neglect sending in the young men's accounts, and is supposed to have burnt large sums of money, by putting into the fire unopened letters, which contained remittances, conveyed remonstrances, and required answers.

At college Parr remained about fourteen months, when his resources were cut off by the sudden death of his father. On balancing his accounts, three pounds seventeen shillings appeared to be all his worldly wealth; and it has been asserted by one of the many persons who have contributed their quota to the memorabilia of Parr, that had he been aware beforehand of possessing so considerable a sum, he would have continued longer in an university which he quitted with a heavy heart, and which he was ever proud to acknowledge as his literary nursing-mother. It is melancholy to reflect on the numbers of young men who squander the opportunities afforded them at Cambridge, and Oxford, without a thought; "casting the pearl away, like the Aethiop," while, at the very moment, many are the sons of genius and poverty, who, with Parr, are struggling in vain to hold fast their chance of the learning, and the rewards of learning, to be gained there, and which would be to them instead of house and land. Thus were Parr's hopes again nipped in the bud, and those years, (the most valuable of all, perhaps, for the formation of character,) the latter years of school and college life, were to him a blank. Meanwhile Dr. Sumner, then master of Harrow, offered him the situation of his first assistant. With this Parr closed; he took deacon's orders in 1769; and five years passed away, as usefully and happily spent as any which he lived to see. It was while he was under-master of Harrow that he lost his cousin, Frank Parr, then a recently elected Fellow of King's College. Parr loved him as a brother; and, though himself receiving a salary of only fifty pounds a year, and, as he says, and as may be well believed, "then very poor," he cheerfully undertook for Frank, by way of making his death-bed more comfortable, the payment of all his Cambridge debts, which proved to be two hundred and twenty-three pounds; a promise which, it is needless to say, he faithfully kept, besides settling an annuity of five pounds upon his mother.

In 1771, when Parr was in his twenty-fifth year, Dr. Sumner was suddenly carried off by apoplexy. Parr now became a candidate for the head mastership of Harrow, founding his claims on being born in the town, educated at the school, and for some years one of the assistants. The governors, however, preferred Dr. Benjamin Heath, an antagonist by whom it was no disgrace to be beaten, and whose personal merit Parr himself allowed to justify their choice. A rebellion among the boys, many of whom took Parr's part, ensued; and in an evil hour he threw up his situation of assistant, and withdrew to Stanmore, a village a very few miles from Harrow. Here he was followed by forty of the young rebels, and with this stock in trade he proceeded to set up a school on his own account. This, Dr. Johnstone thinks, was the crisis of Parr's life. The die had turned up against him, and the disappointment, with its immediate consequences, gave a complexion to his future fortunes, character, and comfort. He had already mounted a full-bottomed wig when he stood for Harrow, anxious, as it should seem, to give his face a still further chance of keeping its start. He now began to ride on a black saddle, and bore in his hand a long wand with an ivory head, like a crosier in high prelatical pomp. His neighbours, who wondered what it could all mean, had scarcely time to identify him with his pontificals, before they saw him stalking along the street in a dirty, striped dressing-gown. A wife was all that was now wanted to complete the establishment at Stanmore, and accordingly Miss Jane Marsingale, a lady of an ancient Yorkshire family, was provided for him, (Parr, like Hooker, appears to have courted by proxy, and with about the same success,) and so Stanmore was set a going as the rival of Harrow. These were fearful odds, and it came to pass, that in spite of "Attic symposia," and groves of Academus, and the enacting of a Greek play, and the perpetual recitation of the fragment in praise of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, the establishment at Stanmore declined, and at the end of five years, Parr was not sorry to accept the mastership of an endowed school at Colchester. To Colchester, therefore, he removed with his wife and a daughter in the spring of 1777. Here he took priest's orders at the hands of Bishop Lowth, and found society congenial to him in Dr. Foster, a kindred whig, and in Thomas Twining, a kindred scholar.

YOUNG NAPOLEON

This poor boy, whose destiny has suffered so remarkable a change, appears to have been a child of great promise, both for intelligence and goodness of heart. The anecdotes concerning him are of the most pleasing kind. From the time that he knew how to speak, he became, like most children, a great questioner. He loved, above every thing, to watch the people walking in the garden and in the court of the Tuileries, over which his windows looked. There was always a crowd of people assembled there to see him. Having remarked that many of the persons who entered the palace, had rolls of paper under their arms, he desired to know of his gouvernante what that meant. He was told that they were unfortunate people, who came to ask some favour of his papa. From this moment he shouted and wept whenever he saw a petition pass, and was not to be satisfied till it was brought to him; and he never failed to present himself, every day at breakfast, all those which he had collected in the course of the day before. It may be easily supposed, that when this practice was known to the public, the child was never at a loss for petitions.

He saw one day under his windows a woman in mourning who held by the hand a little boy about four years old, also in mourning. This little fellow had in his hand a petition which he held up from a distance to the young prince. The boy would know why this poor, little one was clothed all in black. His governess answered that it was, no doubt, because his papa was dead. He manifested a strong desire to talk with the child.—Madame Montesquieu, who seized every occasion of developing his sensibility, consented, and gave an order that he should be brought in with his mother. She was a widow whose husband had been killed in the last campaign, and finding herself without resources, had petitioned the emperor for a pension. The young Napoleon took the petition and promised to deliver it to his papa. The next morning he made up his ordinary packet of petitions, but the one in which he took a particular interest he kept separate, and after putting the mass into the hands of the emperor according to custom; "Papa," said he, "here is the petition of a very unfortunate little boy; you are the cause of his father's dying, and now he has nothing. Give him a pension, I beg." Napoleon took up his son and embraced him tenderly, gave him the pension, which he antedated, and caused the patent to be made out in the course of the day.—Translated from the French.—Westminster Review.

AN ESKDALE ANECDOTE

Extract of a Letter from the Ettrick ShepherdI chanced to be on a weeks' visit to a kind friend, a farmer in Eskdale-muir, who thought meet to have a party every day at dinner, and mostly the same party. Our libations were certainly carried rather to an extremity, but our merriment corresponded therewith. There was one morning, indeed, that several of the gentlemen were considerably hurt, and there were marks of blood on the plaster, but no one could tell what had happened. It appeared that there had been a quarrel, but none of us knew what about, or who it was that fought.

But the most amusing part of the ploy (and a very amusing part it was) regarded a half hogshead of ale, that was standing in the lobby to clear for bottling. On the very first forenoon, our thirst was so excessive, that the farmer contrived to insert a spigot into this huge cask, and really such a treasure I think was hardly ever opened to a set of poor thirsty spirits. Morning, noon, and night, we were running with jugs to this rich fountain, and handing the delicious beverage about to lips that glowed with fervour and delight. In a few days, however, it wore so low, that before any would come, one was always obliged to hold it up behind; and, finally, it ran dry.

On the very morning after that, the farmer came in with a wild raised look. "Gentlemen," said he, "get your hats—haste ye—an' let us gang an' tak a lang wauk, for my mother an' the lasses are on a-scrubbing a whole floorfu' o' bottles; an' as I cam by, I heard her speaking about getting the ale bottled the day."

THE SKETCH-BOOK

CREATING WANTS

An old, but a true StoryI was bred a linen-draper, and went into business with better than a thousand pounds. I married the daughter of a country tradesman, who had received a boarding-school education. When I married I had been in business five years, and was in the way of soon accumulating a fortune. I was never out of my shop before it was shut up, and was remarked by my friends as being a steady young man, with a turn for business.

I used to dine in the parlour, where I could have an eye upon the shop; but my new acquaintances told me this was extremely ungenteel; that if I had no confidence in my men I should get others; that a thief would be a thief, watch him how I would, and that I was now too forward in the world to be a slave to the shop.

From being constantly in my shop from seven in the morning till eight in the evening, I lay in bed till nine, and took a comfortable breakfast before I made my appearance below. Things, however, went on very well—I bowed to my best customers, and attended closely to my business while I was in it, trade went on briskly, and the only effect of this acquaintance was the necessity of letting our friends see that we were getting above the world, by selling some of our old-fashioned furniture, and replacing it with that which was more genteel, and introducing wine at dinner when we had company.

As our business increased, our friends told us it would be extremely genteel to take a lodging in summer just at the outskirts of the city, where we might retire in the evening when shop was shut, and return to it next morning after breakfast; for as we lived in a close part of the town, fresh air was necessary to our health; and though, before I had this airy lodging, I breathed very well in town, yet indulging in the fresh air, I was soon sensible of all the stench and closeness of the metropolis; and I must own I began to relish a glass of wine after dinner as well when alone as when in company: I did not find myself the worse in circumstances for this lodging; but I did not find I grew richer, and we had no money to lay by.

We soon found out that a lodging so near town was smothered with dust, and smelt too much of London air, therefore I took a small house we had seen about five miles from town, near an acquaintance we had made, and thought it imprudent to sleep from home every night, and that it would be better for my business to be in town all the week, and go to this house on Saturday, and continue there until Monday; but one excuse or other often found me there on Tuesday. Coach-hire backward and forwards, and carriage of parcels, generally cost us seven or eight shillings a week; and as a one-horse chaise would be attended with very little more expense, and removing to a further distance, seeing the expense would be saved by not having our house full of company on Sunday, which was always the case, being so near town; besides the exercise would be beneficial, for I was growing corpulent with good living and idleness. Accordingly we removed to the distance of fifteen miles from town, into a better house, because there was a large garden adjoining it, and a field for the horse. It afforded abundance of fruit, and fruit was good for scorbutic and plethoric habits, our table would be furnished at less expense, and fifteen miles was but an hour's ride more than seven miles.

All this was plausible, and I soon found myself under the necessity of keeping a gardener; so that every cabbage that I before put on my table for one penny cost me one shilling, and I bought my dessert at the dearest hand; but I was in it—I found myself happy—in a profusion of fruit, and a blight was little less than death to me.

This new acquired want, now introduced all the expensive modes of having fruit in spite of either blasts or blights. I built myself a small hot house, and it was only the addition of a chaldron or two of coals; the gardener was the same, and we had the pride of putting on our table a pine-apple occasionally, when our acquaintance were contented with the exhibition of a melon.

From this expense we soon got into a fresh one. As we often out-staid Monday in the country, it was thought prudent that I should go to town on Monday by myself, and return in the evening; this being too much for one horse, a second-hand chariot might be purchased for a little more than what the one-horse chaise would sell for; the field was large enough for two horses; going to town in summer in an open carriage was choking ourselves with dust, burning our faces, and the number of carriages on the road made driving dangerous; besides, having now a genteel acquaintance in the neighbourhood, there was no paying a visit in a one-horse chaise. Another horse would be but very little addition in expense; we had a good coach-house, and the gardener would drive. All this seemed true. I fell into the scheme; but soon found that the wheels were so often going that the gardener could not act in both capacities; whilst he was driving the chariot, the hot-house was neglected; the consequence was, that I hired a coachman. The chariot brought on the necessity of a footman—a better acquaintance—wax candles—Sherry—Madeira—French Wines, &c. In short, I grew so fond of these indulgencies that they became WANTS, and I was unhappy when in town and out of the reach of them.

All this would have done very well if I had not had a business to mind; but the misfortune was, that it took me off from trade—unsettled my thoughts; my shopmen were too much left to themselves, they were negligent of my business, and plundered me of my property. I drew too often upon the till—made no reserve for the wholesale dealers and manufacturers—could not answer their demands upon me—and became—Bankrupt.

Reduced now to live upon a chop and a draught of porter, I feel my wants more than ever; my wife's genteel notions having upset her, she has lost her spirits. We do little but upbraid each other, and I am become despicable in my own opinion, and ridiculous in that of others. I once was happy, but now am miserable.

THE GATHERER

GUDE NEWS

Copied from an inscription over the fireplace of a public-house in Edinburgh, the frequent resort of BurnsWillie Christie tells them wha dinna ken, that he has a public house, first door down Libbertown Wynd, in the Lawn Market, whaur he keeps the best o' stuff; gude nappy Yill frae the best o' Bruars in big bottels an' wee anes, an' Porter frae Lunnon o' a' sorts; Whuske as gude as in the Toun, an o' a' strength, an' for cheapness ekwall to ony that's gaun. Jinger Beer in wee bottells at Tippence, an' Sma' Beer for three bawbees the twa bottels out of the house, an' a penny the bottel in.

N.B. Toddy cheap an' unco' gude if 'tis his ain mackin.

S.HEPIGRAM

Whilst Mary kissed her infant care,"You like my lip," she cried, "my dear."The smiling child, though half afraid,Thus to her beauteous mother said:"With me, mamma, oh, do not quarrel,I thought your lip had been my coral."E.A.WAN EXPLETIVE

A newspaper tells us that an old woman died April 26, at Wolverhampton, aged 150 years.

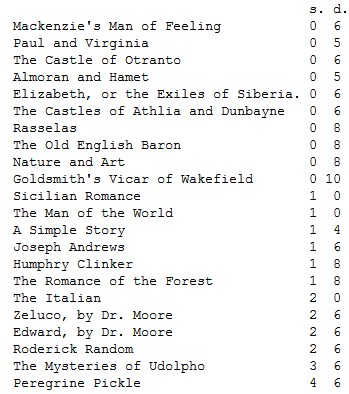

LIMBIRD'S EDITIONof the Following Novels is already Published:

1

The above brief account of a veritable old English Manor House, transcribed from a few rough notes, taken at the period of personal observation, is now supplied by the writer as an article entitled "The Siege of Sawston," appears this month, in that clever and amusing work The United Service Journal.