полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 374, June 6, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 13, No. 374, June 6, 1829

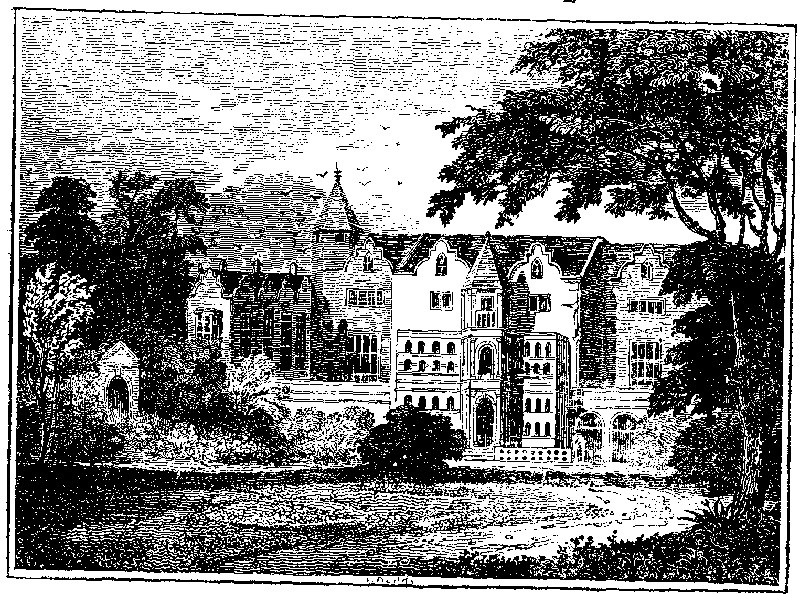

HOLLAND HOUSE, KENSINGTON

Since the time of William III., who was the first royal tenant of the palace, Kensington has been a place of considerable interest, as the residence and resort of many celebrated men. The palace, however, possesses little historical attraction; but, among the mansions of the parish, Holland House merits especial notice.

Holland House takes its name from Henry Rich, Earl of Holland, and was built by his father-in-law, Sir Walter Cope, in the year 1607, of the architecture of which period it affords an excellent specimen. Its general form is that of an half H. The Earl of Holland greatly improved the house. The stone piers at the entrance of the court (over which are the arms of Rich, quartering Bouldry and impaling Cope) were designed by Inigo Jones. The internal decorations were by Francis Cleyne. One chamber, called the Gilt Room, which still remains in its original state, exhibits a very favourable specimen of the artist's abilities; the wainscot is in compartments, ornamented with cross crosslets and fleurs de-lis charges, in the arms of Rich and Cope, whose coats are introduced, entire, at the corner of the room, with a punning motto, alluding to the name of Rich, Ditior est qui se. Over the chimneys are some emblematical paintings, done (as the Earl of Orford observes) in a style and not unworthy of Parmegiane. The Earl of Holland was twice made a prisoner in his own house, first by King Charles, in 1633, upon occasion of his challenging Lord Weston; and a second time, by command of the parliament, after the unsuccessful issue of his attempt to restore the king, in August, 1648. The Earl, who was a conspicuous character during the whole of Charles's reign, and frequently in employments of considerable trust, appears to have been very wavering in his politics, and of an irritable disposition. In 1638, we find him retired to his house at Kensington, in disgust, because he was not made Lord Admiral. At the eve of the civil war, he was employed against the Scots; when the army was disbanded, having received some new cause of offence, he retired again to Kensington, where, according to Lord Clarendon, he was visited by all the disaffected members of parliament, who held frequent meetings at Holland House. Some time afterwards, when the civil war was at its height, he joined the king's party at Oxford; but, meeting with a cool reception, returned again to the parliament. In August 6, 1647, "the members of the parliament who were driven from Westminster by tumults, met General Fairfax at Holland House, and subscribed to the declaration of the army, and a further declaration, approving of and joining with the army, in all their late proceedings, making null all acts passed by the members since July 6." (Clarendon.)– The Earl of Holland's desertion of the royal cause, is to be attributed, perhaps, to his known enmity towards Lord Strafford; he gave, nevertheless, the best proof of his attachment to monarchy, by making a bold, though rash attempt, to restore his master. After a valiant stand against an unequal force, near Kingston upon Thames, he was obliged to quit the field, but was soon after taken prisoner, and suffered death upon the scaffold. His corpse was sent to Kensington, and interred in the family vault there, March 10, 1649. In the July following, Lambert, then general of the army, fixed his headquarters at Holland House. It was soon afterwards restored to the Countess of Holland. When theatres were shut up by the Puritans, plays were acted privately at the houses of the nobility, who made collections for the actors. Holland House is particularly mentioned, as having been used occasionally for this purpose.

The next remarkable circumstance in the history of Holland House, is the residence of Addison, who became possessed of it in 1716, by his marriage with Charlotte, Countess Dowager of Warwick and Holland. It is said that he did not add much to his happiness by this alliance; for one of his biographers, rather laconically observes, that "Holland House is a large mansion, but it cannot contain Mr. Addison, the Countess of Warwick, and one guest, Peace." Mr. Addison was appointed Secretary of State, in 1717, and died at Holland House, June 17, 1719. Addison had been tutor to the young earl, and anxiously, but in vain, endeavoured to check the licentiousness of his manners. As a last effort, he requested him to come into his room when he lay at the point of death, hoping that the solemnity of the scene might work upon his feelings. When his pupil came to receive his last commands, he told him that he had sent for him to see how a Christian could die; to which Tickell thus alludes:—

He taught us how to live; and oh! too highA price for knowledge, taught us how to die!On the death of this young nobleman, in 1721, unmarried, his estates devolved to the father of Lord Kensington, (maternally descended from Robert Rich, Earl of Warwick.) who sold Holland House, about 1762, to the Right Hon. Henry Fox, afterwards Lord Holland, the early years of whose patriotic son, the late C.J. Fox, were passed chiefly at this mansion; and his nephew, the present Lord Holland, is now owner of the estate.

The apartments of Holland House, are, generally, capacious and well proportioned. The library is about 105 feet in length, and the collection of books is worthy of the well known literary taste of the noble proprietor. Here also are several fine busts by Nollekens, and a valuable collection of pictures by Sir Godfrey Kneller, Sir Joshua Reynolds, &c. two fine landscapes by Salvator Rosa, and a collection of exquisite miniatures.

The grounds include about 300 acres, of which about 63 acres are disposed into pleasure gardens, &c. Mr. Rogers, the amiable poet, is a constant visiter at Holland House; and the noble host, with Maecenas-like taste, has placed over a rural seat, the following lines, from respect to the author of the "Pleasures of Memory:"—

Here ROGERS sat—and here for ever dwellWith me, those Pleasures which he sang so well.Holland House and its park-like grounds is, perhaps, the most picturesque domain in the vicinity of the metropolis, although it will soon be surrounded with brick and mortar proportions.

FIELD OF FORTY STEPS

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)I should feel obliged if you could give some account of the story attached to the Brothers' Steps, a spot thus called, which formerly existed in one of the fields behind Montague House. The local tradition says, that two brothers fought there on account of a lady, who sat by and witnessed the combat, and that the conflict ended in the death of both; but the names of the parties have never been mentioned. The steps existed behind the spot where Mortimer Market now stands, and not as Miss Porter says, in her novel of the Field of Forty Steps, at the end of Upper Montague Street. In her story, Miss Porter departs entirely from the local tradition.

H.S. SIDNEY.

ITALIAN IMPROVISATRI

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)Allow me permission, if consistent with the regulations of your interesting miscellany, to submit to you a literary problem. We are informed that there exists, at the present day, in Italy, a set of persons called "improvisatri," who pretend to recite original poetry of a superior order, composed on the spur of the moment. An extraordinary account appeared a short time back in a well known Scotch magazine, of a female improvisatrice, which may have met your notice. Now I entertain considerable doubt of the truth of these pretensions; not that I question the veracity of those who have visited Italy and make the assertion: they believe what they relate, but are, I conceive, grossly deceived. There is something, no doubt, truly inspiring in the air of Italy:

For wheresoe'er they turn their ravish'd eyes,Gay gilded scenes and shining prospects rise,Poetic fields encompass them around,And still they seem to tread on classic ground;For there the muse so oft her harp has strung,That not a mountain rears its head unsung:Renown'd inverse each shady thicket grows,And ev'ry stream in heav'nly numbers flows.Notwithstanding this beautiful description, my scepticism will not allow me to believe in these miraculous genii.

Lord Byron mentions these improvisatri, in his "Beppo," but not in a way that leads me to suppose, he considered them capable of original poetry. Mr. Addison, in his account of Italy, says, "I cannot forbear mentioning a custom at Venice, which they tell me is peculiar to the common people of this country, of singing stanzas out of Tasso. They are set to a pretty solemn tune, and when one begins in any part of the poet, it is odds, but he will be answered by somebody else that overhears him; so that sometimes you have ten or a dozen in the neighbourhood of one another, taking verse after verse, and running on with the poem as far as their memories will carry them."

I am, therefore, inclined to think these "improvisatri" are mere reciters of the great Italian poets. It is probable that the persons who give us these extraordinary accounts of Italian genius, are unacquainted with the literature of that country, and of course cannot detect the imposition.

In Goldsmith's poem, entitled "Retaliation," a line occurs, which is to me unintelligible, at least a part of it. That poet concludes his ironical eulogium on Edmund Burke, thus:—

"In short 'twas his fate, unemployed, or in place, sir,To eat mutton cold, and cut blocks with a razor."The cutting blocks with a razor, I think is obvious enough, but, what is meant by eating mutton cold? I should be obliged by a solution.—HEN. B.

I'LL COME TO YOUR BALL

(For the Mirror.)I'll come to your Ball—dearest Emma,(I had nearly forgotten to say)Provided no awkward dilemmaShould happen to keep me away:For I burn with impatience to see you,All our hopes, all our joys to recall,And you'll find I've no wishes to flee you,When next I shall come to your Ball.Strange men, stranger things, and strange citiesI have seen since I parted from you,But your beauty, your love, and your wit isA charm that has still held me true,And tho' mighty has been the temptation,Your image prevail'd over all,And I still held the fond adorationFor one I must meet at the Ball.I have knelt at the shrine of a Donna,And languish'd for months in her train,But still I was whisper'd by honour,And came to my senses again,When I thought of the vows I had plighted,And the stars that I once used to callAs my witnesses—could I have slighted?Her I long to behold at the Ball.You say that my nature is altered,"I've forgotten the how and the when,That my voice which was best when it faltered"Is rough by my converse with men:Believe me that still you will find meOf lovers the truest of all,And the spell that has bound still shall bind me,And I'll come, dearest girl, to your Ball.I have waded through battle fields gory,To my country and honour been true,And my name has been famous in story,But dear Emma, it all was for you.I've longed when my troubles were over,Unhurt by the bay'net or ball.To forget I was ever "a rover,"And claim you my bride at your Ball.CLARENCE.THE SANJAC-SHERIF, OR STANDARD OF MAHOMET

(For the Mirror.)This standard, which is an object of peculiar reverence among the Mussulman, was originally the curtain of the chamber door of Mahomet's favourite wife. It is kept as the Palladium of the empire, and no infidel can look upon it with impunity. It is carried out of Constantinople to battle in cases of emergency, in great solemnity, before the Sultan, and its return is hailed by all the people of the capital going out to meet it. The Caaba, or black stone of Mecca is also much revered by the Turks; it is placed in the Temple, and is expected to be endowed with speech at the day of judgment, for the purpose of declaring the names of those pious Mussulmen who have really performed the pilgrimage to Mecca, and poured forth their devotions at the shrine of the prophet.—INA.

EATING

Abridged from Mr. Richards's Treatise on Nervous DisordersThe object of eating ought not to be, exclusively, the satisfying of the appetite. It is true that the sensation of hunger admonishes us, and indeed, incites us to supply the wants of the body; and that the abatement of this sensation betokens that such want has been supplied; so far the satisfying of the appetite is a matter of consideration; but a prudent person will observe the mode in which the appetite is best satisfied, and the frame, at the same time, most abundantly nourished, for this ought to be the chief object of feeding. There is much truth in the homely adage, that "what is one man's meat is another man's poison," and a person who has been muscled1 will, if he wishes to enjoy his health, rigidly eschew that piscatory poison. So, also, will an individual with a bilious habit avoid fat pork; and those whose stomachs are flatulent will not inordinately indulge in vegetables. Captain Barclay, whose knowledge in such matters was as extensive as that of most persons, informs us that our health, vigour, and activity must depend upon our diet and exercise.

A leading rule in diet, is never to overload the stomach; indeed, restriction as to quantity is far more important than any rule as to quality. It is bad, at all times, to distend the stomach too much; for it is a rule in the animal economy, that if any of the muscular cavities, as the stomach, heart, bowels, or bladder, be too much distended, their tone is weakened, and their powers considerably impaired.

The consideration of diet might be rendered very simple, if people would but make it so; but from the volumes which have been recently written on diet and digestion, we might gather the alarming information that nearly every thing we eat is pernicious. Far be it from me to adopt such a discouraging theory. My object is rather to point out what is good, than to stigmatize what is bad—to afford the patient, if I can, the means of comfort and enjoyment, and not to tell him of his sufferings, or of the means of increasing them.

To "eat a little and often," is a rule frequently followed, because it is in accordance with our feelings; but it is a very bad rule, and fraught with infinite mischief. Before the food is half digested, the irritable nerves of the upper part of the stomach will produce a sensation of "craving;" but, it is sufficiently evident that, to satisfy this "craving," by taking food, is only to obtain a temporary relief, and not always even that, at the expense of subsequent suffering. There can be no wisdom in putting more food into the stomach than it can possibly digest; and, as all regularity is most conducive to health, it is better that the food should be taken at stated periods. I do not by any means interdict the use of meat; on the contrary, fresh meat, especially beef and mutton, affords great nutriment in a small compass. "Remember," says Dr. Kitchiner, "that an ounce of beef contains the essence of many pounds of hay, turnips, and other vegetables;" and, we should bear in mind, also, that no meat arrives at perfection that is not full-grown. Beef and mutton are consequently better than veal or lamb, or "nice young pork." To these such vegetables may be added, as are easy of digestion, and such as usually "agree" with the individual. If, however, the stomach and bowels be very irritable, and their powers much impaired—if the tongue be dry, and its edges more than commonly red, vegetable diet ought to be considerably restricted. Peas, beans, the different kinds of greens, and all raw fruits, should be avoided, and potatoes, properly boiled, with turnips and carrots, ought to constitute the only varieties. I have seen the skins of peas, the stringy fibres of greens, and the seeds of raspberries and strawberries, pass through the bowels no further changed, than by their exposure to maceration; and it is not necessary to point out the irritation which their progress must have produced, as they passed over the excited and irritable surface of the alimentary canal.

THE SKETCH-BOOK

COWES REGATTA

A SCENE IN THE ISLE OF WIGHT(For the Mirror.)The crowded yachts were anchor'd in the roads,To view the contest for a kingly prize;Voluptuous beauty smil'd on Britain's lords,And fashion dazzled with her thousand dyes;And far away the rival barks were seen,(The ample wind expanding every sail)To climb the billows of the watery green,As stream'd their pennons on the favouring gale:The victor vessel gain'd the sovereign boon;The gothic palace and the gay saloon,Begemm'd with eyes that pierc'd the hiding veil,Echoed to music and its merry gleeAnd cannon roll'd its thunder o'er the sea,To greet that vessel for her gallant sail.Sonnets on Isle of Wight SceneryTo those readers of the MIRROR who have not witnessed an Isle of Wight Regatta, a description of that fête may not be uninteresting. From the days assigned to the nautical contest, we will select that on which his Majesty's Cup was sailed for, on Monday, the 13th of August, 1827, as the most copious illustration of the scene; beginning with Newport, the fons et origo of the "doings" of that remembered day. Dramatically speaking, the scene High-street, the time "we may suppose near ten o'clock," A.M.; all silent as the woods which skirt the river Medina, so that to hazard a gloomy analogy, you might presume that some plague had swept away the population from the sunny streets; the deathlike calm being only broken by the sounds of sundry sashes, lifted by the dust-exterminating housemaid; or the clattering of the boots and spurs of some lonely ensign issuing from the portals of the Literary Institution, condemned to lounge away his hours in High-street. The solitary adjuncts of the deserted promenade may be comprised in the loitering waiter at the Bugle, amusing himself with his watch-chain, and anxiously listening for the roll of some welcome carriage—the sullen urchin, reluctantly wending his way to school, whilst

"His eyesAre with his heart, and that is far away;"amidst the assemblage of yachts and boats, and dukes and lords, and oranges and gingerbread, at Cowes Regatta.

But where is all Newport? Why, on the road to Cowes, to be sure; for who dreams of staying at home on the day of sailing for the King's Cup? If the "courteous reader" will accompany us, we will descant on the scenery presented on the road, as well as the numerous vehicles and thronging pedestrians will permit us. Leaving the town-like extent of the Albany Barracks, the prospect on the left is the Medina, graced with gently gliding boats and barges, and skirted by fine woods. Opposite is the wood-embosomed village of Whippingham, from which peers the "time-worn tower" of the little church. Passing another romantic hamlet (Northwood) the river approaching its mighty mother, the sea, widens into laky breadth; and here the prospect is almost incomparable. On a lofty and woody hill stands the fine modern castellated residence of John Nash, Esq. an erection worthy of the baronial era, lifting its ponderous turrets in the gleaming sunshine; and on another elevation contiguous to the sea, is the castle of the eccentric Lord Henry Seymour, a venerable pile of antique beauty. Here the spectator, however critical in landscape scenery, cannot fail to be gratified; the blended and harmonizing shades of wood, rock, and water; the diversities of architecture, displayed in castle, cottage, and villa; the far-off heights of St. George's and St. Catherine's overtopping the valley; the fine harbour of Cowes, filled with the sails of divers countries, and studded with anchored yachts, decked in their distinguishing flags; and around, the illimitable waters of the ocean encircling the island, form an interesting coup d'oeil of scenery which might almost rival the imaginary magnificence of Arcadia.

Approaching Cowes by the rural by-road adjoining Northwood Park, the residence of George Ward, Esq. the ocean scenery is sublimely beautiful. In the distance is seen the opposite shores, with Calshot Castle, backed by the New Forest, and one side of it, divided by Southampton Water, and the woods of Netley Abbey. Here we descried the contending yachts, ploughing their way in the direction of the Needles; but as our acquaintance with the sailing regulations of the Royal Yacht Club will not admit of our awarding the precedence to one or the other, we will descend from the elevation of Northwood, amidst the din of music from the Club House, and the hum of promenaders on the beach, and ensconce ourselves in the snug parlour of "mine host" Paddy White, whom we used to denominate the Falstaff of the island. Though from the land of shillelaghs and whiskey, Paddy is entirely devoid of that gunpowder temperament which characterizes his country; and his genuine humour, ample obesity, and originality of delivery, entitle him to honourable identification with "Sir John." Now, by the soul of Momus! who ever beheld a woe-begone face at Paddy White's? Even our own, remarkable for "loathed melancholy," has changed its moody contour into the lineaments of mirth, while listening to him. View him holding forth to his auditors between the intervening whiffs of his soothing pipe, and you see written in wreaths of humour on his jolly countenance, the spirit of Falstaff's interrogatory, "What, shall I not take mine ease at mine inn?" The most serious moods he evinces are, when after detailing the local chronology of Cowes, and relating the obituary of "the bar," consisting of the deaths of dram-drinking landladies, and dropsical landlords, he pathetically relaxes the rotundity of his cheeks, and exclaims, "Poor Tom! he was a good un." But we must to the beach, and glance at the motley concourse assembled to behold the nautical contest.

Was there ever a happier scene than Cowes presented on that day? But to begin with the splendid patrons of the festival, we must turn our eyes to the elegant Club House, built at the expense of George Ward, Esq. Before it are arranged the numerous and efficient band of the Irish Fusileers, and behind them, standing in graceful groups, are many of the illustrious members of the club. That elderly personage, arrayed in ship habiliments, is the noble Commodore, Lord Yarborough; he is in conversation with the blithe and mustachioed Earl of Belfast. To the right of them is the Marquess of Anglesey, in marine metamorphose; his face bespeaking the polished noble, whilst his dress betokens the gallant sea captain. There is the fine portly figure of Lord Grantham, bowing to George Ward, Esq.; who, in quakerlike coat and homely gaiters, with an umbrella beneath his arm, presents a fine picture of a speculator "on 'Change." To the left is Richard Stephens, Esq., Secretary to the Royal Yacht Club, and Master of the Ceremonies. He is engaged in the enviable task of introducing a party of ladies to view the richly-adorned cups; and the smile of gallantry which plays upon his countenance belies the versatility of his talent, which can blow a storm on the officers of a Custom House cutter more to be dreaded than the blusterings of old Boreas. That beautiful Gothic villa adjoining the Club House, late the residence of the Marquess of Anglesey, is occupied by the ladies of some of the noble members of the club, forming as elegant and fashionable a circle as any ball-room in the metropolis would be proud to boast of. But it is time to speak of the crowd on the beach—lords and ladies—peers and plebeians—civilians and soldiers—swells and sailors—respectable tradesmen and men of no trade—coaches and carriages, and "last, not least," the Bards of the Regatta—

"Eternal blessings be upon their heads!The poets—"singing the deeds of the contested day in strains neither Doric nor Sapphic, but in such rhythm and measure as Aristotle has overlooked in the compilation of his Poetic Rules; and to such music as might raise the shade of Handel from its "cerements." Surely the Earl of Belfast must feel himself highly flattered by the vocal compliment—

"And as for the Earl of Belfast, he's a nobleman outright,They all say this, both high and low, all through the Iley Wight."Reverting to the aquatic scenery, the most prominent object amidst the "myriad convoy," is the Commodore's fine ship, the Falcon, 351 tons, lying out a mile and a half to sea. Contrasting her proportions with the numerous yachts around her, we might compare her commanding appearance to that of some mountain giant, seated on a precipice, and watching the trial for mastery amongst a crowd of pigmies below. Her state cabin has been decorated in a style of magnificence for a ball in the evening, at which 200 of the nobility and gentry are expected to be present. But all eyes are anxiously turned to the race. "Huzza for the Arrow," is the acclamation from the crowd; and certain enough the swift Arrow, of 85 tons, Joseph Weld, Esq., has left her opponents, even the favourite Miranda spreads all sail in vain—the Arrow flies too swiftly, outstripping the Therese, 112 tons; the Menai, 163 tons; the Swallow, 124 tons; the Scorpion, 110 tons; the Pearl, 113 tons; the Dolphin, 58 tons; and the Harriet, 112 tons. Now she nears the starting vessel, gliding swiftly round it—the cannons on the battlements of Cowes Castle proclaim the victory—the music breaks forth "with its voluptuous swell," amidst the applause of the multitude,—and his Majesty's Cup is awarded to the Arrow.