полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 550, June 2, 1832

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 19, No. 550, June 2, 1832

RARE ARCTIC BIRDS

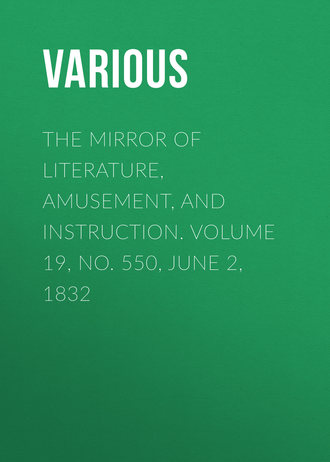

THE WHITE-HORNED OWL

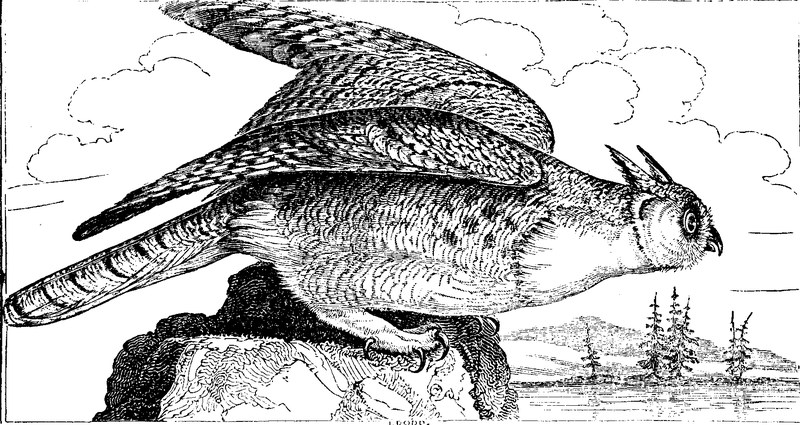

THE COCK OF THE PLAINS

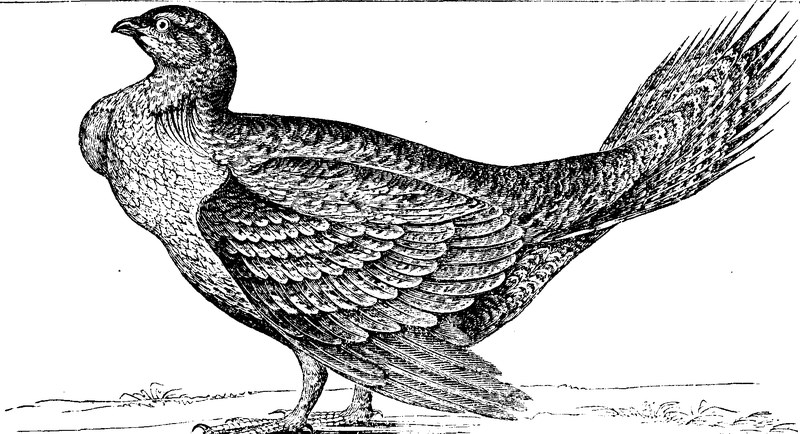

LEGS AND FEET OF THE MOUNTAIN GROUSE.

Few of the results of recent expeditions of discovery have been so interesting to the public as their contributions to zoological history. Many important additions to geographical science have also been made by these journeys into countries hitherto unexplored, or but imperfectly known by Europeans; but the interest is not of that attractive character which is more or less attached to the natural history of these districts. The great delight that we take in the latter species of knowledge is referable to the curiosity we feel respecting the inhabitants of a country after we have once been assured of its existence. Our first inquiries naturally enough relate to the tenants of our own species; we then ask what description of quadrupeds are found over its plains, and how far they enlarge or circumscribe the enjoyments and liberty of sovereign man; the birds that warble in its groves, the insects that flutter in its breeze, the fish that tenant its seas, rivers, and lakes, and the plants that wave in wild luxuriance on its hills and dales; and by comparing all these varieties with the natural characteristics of our own country, and contrasting their differences with others, we are enabled, in some degree, to appreciate, by the linked gradations, the order and harmony that reign throughout nature—the minute beauty of parts which are so essential to the perfection of the grand whole.

The last overland expedition to the Polar sea, under the command of Captain Sir John Franklin, was peculiarly fortunate in the collection of objects of natural history, which indeed were too numerous for the limits of an appendix, such as had appeared with the narratives of previous expeditions. Hence the number of the specimens warranted their publication in a separate form, under the able superintendance of Dr. Richardson, surgeon and naturalist to the expedition, aided by Mr. Swainson. The great expense of the requisite embellishment of the ornithological portion, however, threatened a formidable obstacle to its completeness; but this was met by a liberal grant of one thousand pounds by the British Government, to be applied solely towards the expense of the engravings—the present being the first zoological work ever published with the sterling assistance of His Majesty's Treasury. The first part of this truly great national work appeared some time since, with 28 spirited figures of Mammalia, from drawings by Landseer; the entomological and botanical parts are preparing for publication; and that of The Birds, (to which we are indebted for the annexed Cuts,) has very recently appeared.1

Dr. Richardson, with zealous attachment to his pursuits, passed seven summers and five winters surrounded by the objects he has described with such fidelity. He is, therefore, not a mere book naturalist, but he has studied the habits and zoological details of the living animals; Mr. Swainson having assisted the Doctor in the systematic arrangement and production of the plates. Their descriptions include all the birds hitherto found over an immense expanse of country of the 49th parallel of latitude, and east of the Rocky Mountains, which lie much nearer to the Pacific Coast than to the eastern shore of America: many of these birds being, for the first time, made known to ornithologists. We have selected two of the most singular in their conformation: one from the Owls, which are numerous and beautiful; and the other from the Grouse, of which ten fine species are described.2

THE ARCTIC, OR WHITE-HORNED OWL,

Strix (Bubo) Arctica, SWAINSON.

This very beautiful owl appears to be rare, only one specimen having been seen by the members of the Expedition. It was observed flying at mid-day in the immediate vicinity of Carlton House, and was brought down with an arrow by an Indian boy. Dr. Richardson could obtain no information respecting its habits.

From Mr. Swainson's minute description we learn that the colour of the bill and claws is blueish black. The face is white, and a band of blackish-brown and white crosses the throat. The egrets or ear feathers are tipped with blackish-brown, the inner webs being white varied with wood-brown. The whole of the back is marked with undulated lines or fine bars of dark umber-brown, alternating with white: on the greater wing coverts the white is replaced by pale wood-brown. The primary and secondary feathers are wood-brown, margined inwards with white. They are crossed by umber-brown bars on both webs, the intervening spaces being finely speckled with the same. On the tertiary feathers, the wood-brown is mostly replaced by white. The tail-feathers are white, deeply tinged inwards by wood-brown, and crossed by bars of umber-brown; the tips are white. The chin is white. The throat is crossed by the band already mentioned, behind which there is a large space of pure snow white, that is bounded on the breast by blotches of liver-brown situated on the tips of the feathers. The belly and long plumage of the flanks are white, crossed by narrow bars of dark brown. The under tail coverts, thighs, and feet are pure white. The linings of the wings are pure white with the exception of a brown spot on the tips of the great interior coverts. The bill is strong, curved from the base, moderately compressed towards the tip, with a very obtuse ridge. The facial disk is small, and incomplete above the orbit. The egrets are more than two inches long, each composed of six or seven feathers, and situate behind the upper end of the black band bounding the face. The folded wings fall about three inches and a half short of the tail, which is rounded, the outer feathers being an inch shorter than the central ones. The plumage of the sides of the belly is long, and hangs down over the thighs. The thigh feathers are very downy, but are not long. The tarsi are rather long, and the toes are moderately long; they are clothed to the roots of the nails by a close coat of hairy feathers. The claws are strong, sharp, and very much curved.

The length of the bird from the tip of the bill to the end of the tail is 21 inches 6 lines; and the length of the longest quill feather is 12 inches six lines.

THE COCK OF THE PLAINS,

Tetrao, 3 (Centrocercus,) Urophasianus,

SWAINSON.

This bird, which was first mentioned by Lewis and Clark,4 has since become well known to the fur traders that frequent the banks of the Colombia. Several specimens have been sent to England by the agents of the Hudson's Bay Company. Mr. David Douglas has published the following account of the manners of the species, the only one hitherto given.

"The flight of these birds is slow, unsteady, and affords but little amusement to the sportsman. From the disproportionately small, convex, thin-quilled, wing,—so thin, that a vacant space, half as broad as a quill appears between each,—the flight may be said to be a sort of fluttering more than any thing else: the bird giving two or three claps of the wings in quick succession, at the same time hurriedly rising; then shooting or floating, swinging from side to side, gradually falling, and thus producing a clapping, whirring sound. When started, the voice is 'cuck, cuck, cuck,' like the common pheasant. They pair in March and April. The love-song is a confined, grating, but not offensively disagreeable, tone,—something that we can imitate, but have a difficulty in expressing—'Hurr-hurr—hurr-r-r-r hoo,' ending in a deep hollow tone, not unlike the sound produced by blowing into a large reed. Nest on the ground, under the shade of Purshia and Artemisia, or near streams, among Phalaris arundinacea, carefully constructed of dry grass, and slender twigs. Eggs from thirteen to seventeen, about the size of those of a common fowl, of a wood-brown colour, with irregular chocolate blotches on the thick end. The young leave the nest a few hours after they are hatched. In the summer and autumn months these birds are seen in small troops, and in winter and spring in flocks of several hundreds. Plentiful through the barren arid plains of the river Colombia; also in the interior of North California. They do not exist on the banks of the river Missouri; nor have they been seen in any place east of the Rocky Mountains."

The general colour of the upper plumage is light hair-brown, mottled and variegated with dark umber-brown and yellowish-white. The under plumage is white and unspotted on the breast and part of the body; but dark umber-brown, approaching to black, on the lower hall of the body, and part of the flanks; the latter towards the vent are marked as on the upper plumage. The under tail coverts are black, broadly tipped with white. The feathers of the thighs and tarsi are light hair-brown, mottled with darker lines. The throat and region of the head is varied with blackish on a white ground. The shafts of all the feathers on the breast are black, rigid, and look like hairs; but those of the scale-like feathers of the sides are white and thicker. The bill and toes are blackish. The bill is thick and strong: the ridge is advanced to a remarkable extent towards the front, and divides the thickset feathers which cover the nostrils by a convex ridge of three quarters of an inch long. This is a very peculiar and important character, since it plainly indicates the analogy of this form to Ramphastos, Buceros,5 and numerous other rasorial types. On each side the breast, the present specimen exhibits two prominent naked protuberances, as in the female bust, perfectly destitute of hair or feathers. On each side of these protuberances, and higher up on the neck, is a tuft of feathers, having their shafts considerably elongated and naked, gently curved, and tipped with a pencil of a few black radii; they are placed much behind the naked protuberances, and do not appear intended to cover them when not inflated. On the sides of the neck, and across the breast, below the protuberances, the feathers are particularly short, rigid, and acute, laying over each other with the same compactness and regularity as the scales of a fish, excepting that their extremities are not rounded, but acutely pointed. Lower down the breast these feathers, however, begin to assume more of the ordinary shape; but the shafts still remain very thick and rigid, while each is terminated by a slender, naked filament, hornlike, shining, and somewhat flattened towards the end, where there are a few obsolete radii. The wings in proportion to the size of the bird, are very short; the lesser quills ending in a point. The tail is rather lengthened and considerably rounded, each feather lanceolate, and gradually attenuated to a fine point. The tarsi are somewhat elevated, thickly clothed with feathers to the base of the toes, and over the membrane which connects them. The length of this bird Mr. Swainson thinks to have been 25 inches. The female bird, it should be added, has neither the scale-like feathers nor projecting shafts of the male.

The CLAW is that of the PILEATED WOODPECKER, (Picus Dryotomus) Pileatus, SWAINSON, which has much less power than the claw of the typical Woodpecker; the anterior toe (i.e. middle toe,) being longer and stronger than the posterior—a structure the very reverse of that which characterizes the typical species.

LEGS AND FEET of the ROCKY MOUNTAIN SPOTTED GROUSE, (Tetrao Franklinii, DOUGLAS,) which are thickly covered with long and hair-like feathers. The bird inhabits the valleys of the Rocky Mountains from the sources of the Missouri to those of the Mackenzie, and Mr. Douglas informed Dr. Richardson that it is sparingly seen on the elevated platforms which skirt the snowy peaks of Mount Hood, Mount St. Helens, and Mount Baker. He adds, "It runs over the shattered rocks, and among the brushwood with amazing speed, and only uses its wings as a last effort to escape."

The birds of North America include about 320 species. They are divided into migratory and resident; though comparatively few in the fur countries are strictly entitled to be called resident. The raven and Canadian and short-billed jays were the only species recognised as being equally numerous at their breeding-places in winter and summer. Many of the species which raise two or more broods within the United States rear only one in the fur countries, the shortness of the summer not admitting of their doing more. We have mentioned the number and beauty of the hawks and owls. The white-headed eagle inhabits the fur countries as well as the United States. The melody of the song-birds is described to be exquisite. The verdant lawns and cultivated glades of Europe fail in producing that exhilaration and joyous buoyancy of mind which travellers have experienced in treading the Arctic wilds of America, when their snowy covering had just been replaced by an infant but vigorous vegetation. The duck family are, however, the birds of the greatest importance, as they furnish, in certain seasons of the year, in many extensive districts, almost the only article of food that can be procured. The arrival of the water-fowl, it is said, marks the commencement of spring and diffuses as much joy among the wandering hunters of the Arctic regions, as the harvest or vintage in more genial climates. The period of their emigration southwards again, in large flocks, at the close of summer, is another season of plenty bountifully granted to the natives, and enabling them to encounter the rigour and privations of a northern winter.

Dr. Richardson acknowledges the liberal assistance afforded him by the Hudson's Bay Company, in the collection of specimens. Indeed, to this public-spirited body are we indebted for our earliest systematic knowledge of the Hudson's Bay birds. The reader may likewise witness a few living evidences of the Company's liberality, in the fine collection of eagles and owls presented by them to the Zoological Society, and exhibiting in the Gardens in the Regent's Park. Such devotion to the advancement of science cannot be too proudly perpetuated in the history of a society established for commercial objects.

SONNET

TO H–C. ON MY FRIEND H– S– BEING IN LOVE WITH HER(For the Mirror.)Thou that art like the sun, that on its way,Across the cloudless distance of the skiesGives pleasure to us all—no rivalriesLessen'ng the love we bear it—as a dayOf shower-glad April or the month of May,Thou that art cheerful—see yon youth that liesWeeping for want of sunshine from thine eyes,And hope that thou canst only give him—say:"Sweet youth, and art thou weeping for a heartAll passion, joy, and gladness—come unto me,Oft by the evening sunset thou shalt woo me,And as thou hast the gentleness and artOr rather truth-kind nature thou mayst tear itFrom all its other likings, win and wear it."J.H.H.MRS. HEMANS

(To the Editor.)I have just been perusing in No. 16, of Chambers's Edinburgh Journal, a short and incorrect sketch of that highly-gifted and moral poetess, Mrs. Hemans, "who," the writer says, "first came into public notice about twelve or fourteen years ago;" whereas, her literary career commenced as far back as the year 1809, in an elegantly printed quarto of poems, which were highly spoken of by the present T. Roscoe, Esq. and were dedicated by permission to his late Majesty, when Prince Regent. Permit me to say that this accomplished daughter of the Muse is a native of Denbighshire, North Wales, and was born at the family mansion named "Grwych," about one and a half mile distant from Abergele; and at the period of her first appearance as an authoress, she had not, I think, reached her thirteenth year. I had the pleasure of then being her neighbour, and our Appenine mansion, the Signal Station, at Cave Hill, has been more than once enlivened by Lady, then Miss Felicia Dorothea Browne's society, accompanied by her excellent mother. She has since married – Hemans, Esq., then an Adjutant in the army. A great number of her pieces have appeared in the Monthly Magazine, as well as the New Monthly, and although a pleasing pensiveness and sombre cast of mind seem to pervade her beautifully mental pictures, she was, I may say, noted in her youth for the buoyancy and sprightliness of her conversation and manner, which made her the delight and charm of every society with which she mixed. She likewise (I think in the same year) published an animated poem upon the valour of Spain and her patriotic ally, England. Instead of Mrs. H. residing, as the writer of the above memoir observes, chiefly in London, she has passed the principal years of her life since her removal from Grwych, at a pleasant dwelling, termed "Rose Cottage," near the city of St. Asaph. The Editor of the Edinburgh Journal is again wrong in saying that her "Songs of the Affections," and the "Records of Woman," are understood to have had a very limited circulation, whereas, in the space of two years, they have reached a third and fourth edition.

The Author of A Tradesman's Lays.

MASSENA'S TOMB

PERE LA CHAISE, PARIS(For the Mirror.)"The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power,And all that beauty, all that wealth, ere gave,Await alike the inevitable hour,The paths of glory lead but to the grave!"GRAY.Rest Soldier! not the trumpet's peal,Can break the hallow'd silence here;For ling'ring footsteps only steal,To weep the mourner's bitter tear.Sad trophied "city of the dead!"Far around are night dews weeping;And cypresses their branches spread,Where the fair and brave are sleeping.Affection brings her wreath of willow,And fondly decks the funeral stone,The cold, damp earth she makes her pillow,And only hears the night-wind's moan.And hoary age, hath laid him down,With the weary weight of years upon him!And youth, in his spring morning flown,Ere life's cold hues had shadow'd on him.Beauty, hath joined the assembly here,With marble brow, and close-shut eye,And pallid lip,—while o'er her bier,The dirge was chanted mournfully.And roses bloom on many a grave,With lilies fair, and violets blue,And willows their green branches wave,Shedding pale evening's tears of dew.Round many a tomb that flow'ret springs,"Forget me not"—the tale it tells,Vainly the fond appeal it bringsTo Death's domain, where silence dwells!Long years, "with all their deeds," may roll,Ere the cold clay, its cell forsaking,Shall join the disembodied soul,When the last morning's dawn is breaking! Kirton Lindsey. ANNE R.THE WRITINGS OF BURKE

(For the Mirror.)Of all the great men of his age, there were few who attained to the celebrity of Edmund Burke; there were many, however, who deserved it more and whom a more adverse fortune compelled to languish in comparative obscurity. That Burke was a man of wonderful talent it would be in vain to deny, and indeed such denial would be only a proof of our own ignorance and bad taste; but his strength was that of imagination merely,—his genius was not sufficiently counterbalanced by judgment, and he has been at all times ranked as an elegant rather than a nervous writer. In his oratory, as well us his literary composition, he was too much addicted to a florid phraseology, and his hearers, during his lifetime, as well as his readers now, were often driven to consider his meaning, and not unfrequently to make one out for themselves. This style of declamation has been not unaptly called "splendid nonsense," and it was after a display of this sort from Burke, that one of his audience made this pithy exclamation: "It is all very well, but I should like to hear it over again, that I might consider the sense." Burke also dealt in paradoxes occasionally; in short, he will seldom satisfy a careful reader, and his most ardent admirers have been known to confess themselves rather pleased than edified by his works. By way of specimen, as to the remarks we have ventured to make, we shall endeavour to take to pieces the following sophism, for a sophism we cannot help considering it:—

"Duties are not voluntary; duty and will are even contradictory terms."—"Men have an extreme disrelish to be told of their duty; this is, of course, because every duty is a limitation of power."

These two sentences are taken from different parts of the writings of Burke, but they are the same in tendency, though not in expression; they imply simply, that duty is a restraint, and that our duties and our inclinations call us different roads. Let us first consider what the term "duty" signifies. From Johnson we get this explanation of it: "What we are bound to do by the impulse of nature, the dictates of law, or the voice of reason." Now, to take these three cases as they stand, nature has surely ordained everything for our advantage, and therefore in obeying her, we have rather an accession than a diminution of power; with respect to ourselves, the calls of nature are even agreeable to us; and as far as our duties concern others, men seem in general to perform their natural duties willingly, such as a duty to a child, a parent, &c. Then with regard to the duties imposed on us by law, many of these appear indeed at first to be great and unnecessary restraints, but if we examine the matter, we shall find that very few laws have been framed that have not rather good than evil for their object. Society doubtless imposes many restrictions on its members, but it also confers far greater comparative advantages in lieu of them, so that if we were fairly to weigh the benefits received, against the losses sustained, we should find law to be a blessing, without which we could not exist in any real comfort; and we should see clearly then it gives power and elevates, rather than shackles or debases us. As to these legal duties being voluntary with all men, every day proves that they are not; but with all reasonable persons they must be, for we ought surely to perform that willingly, which is not only intended, but actually is, for our good. It is the perverse nature of man, that looks on the dark side of things, and forgetting the ultimate advantage to be derived, considers only the partial and trivial annoyances that necessarily attend its completion. The duties dictated by reason are the only duties that remain: it is difficult to separate these entirely from natural duties; perhaps I may be allowed to call "Prayer" or "Thanksgiving to God" a reasonable duty, (for it is not a natural one, or the brutes would practise it in common with ourselves.) Now this is a duty, that if it is performed at all, is performed voluntarily, for it is clearly in a man's own choice to do it or not, there being no compulsory power to enforce prayer; as to this duty being a limitation of power, its observance does indeed imply a state of dependence, and is an indirect admission that we are creatures at the disposal of another; but that is not exactly the point; it is no limitation of power in this sense; it takes away no power we were before possessed of.

F.

THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

BRITISH WARRIORS

The second volume of the Rev. Mr. Gleig's Lives of the most eminent British, Military Commanders, (and the 28th No. of the Cabinet Cyclopædia,) contains Peterborough and Wolfe, and concludes Marlborough. The latter is very copious, and perhaps more detailed than we expected to find it. We subjoin an extract describing the last days of

Marlborough.

"The stream of public events has hurried us on so rapidly, that we have found little leisure to record those domestic trials, to which, in common with the rest of his species, the great Marlborough was subject. One of these, the death of the young and promising Marquess of Blandford, was a blow which the duke felt severely when it overtook him, and which to the last he ceased not to deplore. Another bereavement he suffered on the 22nd of March, 1714, by the premature decease of his daughter, Lady Bridgewater, in the twenty-sixth year of her age. Lady Bridgewater was an amiable and an accomplished woman, imbued with a profound sense of religion, and beloved both by her parents and her husband. But she possessed not the same influence over the former, which her sister Anne, Countess of Sunderland, exercised, on no occasion for evil, on every occasion for a good purpose. Of the society of this excellent woman, who had devoted herself since his return to dull the edge of political asperity, and to control the capricious temper of her mother, Marlborough was likewise deprived. After bearing with Christian fortitude a painful and lingering illness, she was attacked, in the beginning of April, 1716, with a pleurisy, against which her enfeebled constitution proved unable to oppose itself, and on the 15th she died, at the early age of twenty-eight. Like Rachel weeping for her children, Marlborough refused to be comforted. He withdrew to the retirement of Holywell, that he might indulge his sorrow unseen; and there became first afflicted by that melancholy distemper, under which first his mind and eventually his body sunk.