полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 346, December 13, 1828

EPIGRAM

From the Greek Anthology, (Author unknown.)BY THE REV. W. SHEPHERDIf at the bottom of the cask,Be left of wine a little flask,It soon grows acid:—so when man,Living through Life's most lengthened span.His joys all drain'd or turn'd to tears,Sinks to the lees of fourscore years,And sees approach Death's darksome hour—No wonder if he's somewhat sour!The Winter's Wreath.PORTRAIT PAINTING

The good portrait painter always flatters; for it is his business, not, indeed, to alter and amend features, complexion, or mien, but to select and fix (which it demands genius and sense to do) the best appearance which these ever do wear. Happy the creature of sense and passion who has always with him that self which he could take pleasure in contemplating! Happy—to pass graver considerations—the fair one whose countenance continues as youthful as her attire! When Queen Elizabeth's wrinkles waxed deep and many, it is reported that an unfortunate master of the mint incurred disgrace by a too faithful shilling; the die was broken, and only one mutilated impression is now in existence. Her maids of honour took the hint, and were thenceforth careful that no fragment of looking-glass should remain in any room of the palace. In fact, the lion-hearted lady had not heart to look herself in the face for the last twenty years of her life; but we nowhere learn that she quarrelled with Holbein's portraitures of her youth, or those of her stately prime of viraginity by De Heere and Zucchero.

He who has "neither done things worthy to be written, nor written things worthy to be read," takes the trouble of transmitting his portrait to posterity to very little purpose. If the picture be a bad one, it will soon find its way to the garret; if good, as a work of art, it will perpetuate the fame, probably the name, indeed, of the artist alone. These are the obscurorum virorum imagines which, as Walpole said, "are christened commonly in galleries, like children at the Foundling Hospital, by chance"—Q. Rev.

LOSING A SHOE AND A DINNER

As Ozias Linley, Sheridan's brother-in-law, was one morning setting out on horseback for his curacy, a few miles from Norwich, his horse threw off one of his shoes. A lady, who observed the accident, thought it might impede Mr. Linley's journey, and seeing that he himself was unconscious of it, politely reminded him that one of his horse's shoes had just come off. "Thank you, madam," replied Linley; "will you then have the goodness to put it on for me?"

Linley one day received a card to dine with the late archbishop of Canterbury, who was then bishop of Norwich. Careless into what hole or corner he threw his invitations, he soon lost sight of the card, and forgot it altogether. A year revolved, when, on wiping the dust from some papers he had stuck on the glass over the chimney, the bishop's invitation for a certain day in the month (he did not think of the year one instant,) stared him full in the face, and taking it for granted that it was a recent one, he dressed himself on the appointed day, and proceeded to the palace. But his diocesan was not in London, a circumstance of which, though a matter of some notoriety to the clergy of the diocese, he was quite unconscious; and he returned dinnerless home.

SENTIMENT AND APPETITE

We remember an amiable enthusiast, a worshiper of nature after the manner of Rousseau, who, being melted into feelings of universal philanthropy by the softness and serenity of a spring morning, resolved, that for that day, at least, no injured animal should pollute his board; and having recorded his vow, walked six miles to gain a hamlet, famous for fish dinners, where, without an idea of breaking his sentimental engagement, he regaled himself on a small matter of crimped cod and oyster sauce—Q. Rev.

FORTIFICATION

The walls of Tenchira, in Africa, form one of the most perfect remaining specimens of ancient fortification. They are a mile and a half in circuit, defended by 26 quadrangular towers, and admitting no entrance but by two opposite gates.

MEDIOCRITY, in poetry, is intolerable to gods and to booksellers, and to all intermediate beings.

SONNET TO THE CAMELLA JAPONICA

BY W. ROSCOE, ESQSay, what impels me, pure and spotless flower,To view thee with a secret sympathy?—Is there some living spirit shrined in thee?That, as thou bloom'st within my humble bower,Endows thee with some strange, mysteriouspower,Waking high thoughts?—As there perchancemight beSome angel-form of truth and purity,Whose hallowed presence shared my lonely hour?—Yes, lovely flower, 'tis not thy virgin glow,Thy petals whiter than descending snow,Nor all the charms thy velvet folds display;'Tis the soft image of some beaming mind,By grace adorn'd, by elegance refin'd,That o'er my heart thus holds its silent sway.The Winter's Wreath.PIGS

One day when Giotto, the painter, was taking his Sunday walk, in his best attire, with a party of friends, at Florence, and was in the midst of a long story, some pigs passed suddenly by, and one of them, running between the painter's legs, threw him down. When he got on his legs again, instead of swearing a terrible oath at the pig on the Lord's day, as a graver man might have done, he observed, laughing, "People say these beasts are stupid, but they seem to me to have some sense of justice, for I have earned several thousands of crowns with their bristles, but I never gave one of them even a ladleful of soup in my life."—Lanzi.

TURKISH FIREMEN

The firemen of Constantinople are accused of sometimes discharging oil from their engines instead of water.

SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

FLIES

Cruelty to animals is a subject which has deservedly attracted parliamentary investigation. It is not beneath the dignity of a Christian legislator to prevent the unnecessary sufferings of the meanest of created things; and a law which is dictated by humanity can surely be no disgrace to the statute-book. Who that has witnessed the barbarous and unmanly sports of the cock-pit and the stake—the fiendlike ingenuity displayed by the lord of the creation in teaching his dependents to torture, mangle, and destroy each other for his own amusement—the cruelties of the greedy and savage task-master towards the dumb labourer whose strength has decayed in his service—or the sufferings of the helpless brute that drags with pain and difficulty its maimed carcass to Smithfield—what reasonable being that has witnessed all or any of this, will venture to affirm that interference is officious and uncalled for? Yet it is certain that Mr. Martin acted properly and wisely in excluding flies from the operation of his act—well knowing, as he must have done, that the feeling of the majority was decidedly averse from affording parliamentary countenance and immunity to those descendants of the victims of Domitian's just indignation; although it is understood that such a provision would have been cordially supported by the advocates for universal toleration. The simple question for consideration would be, whether the conduct and principles of the insect species have undergone such a material change as to entitle them to new and extraordinary enactments in their favour? Have they entirely divested themselves of their licentious and predatory habits, and learnt now for the first time to distinguish between right and wrong? Do they understand what it is to commit sacrilege? To intrude into the sanctum sanctorum of the meat-safe? To rifle and defile the half roseate, half lily-white charms of a virgin ham? To touch with unhallowed proboscis the immaculate lip of beauty, the unprotected scalp of old age, the savoury glories of the kitchen? To invade with the most reckless indifference, and the most wanton malice, the siesta of the alderman or the philosopher? To this we answer in the eloquent and emphatic language of the late Mr. Canning—No! Unamiable and unconciliating monsters! The wildest and most ferocious inhabitants of the desert may be reclaimed from their savage nature, and taught to become the peaceful denizens of a menagerie—but ye are altogether untractable and untameable. Gratitude and sense of shame, the better parts of instinct, have never yet interposed their sacred influence to prevent the commission of one treacherous or unbecoming action of yours. The holy rites of hospitality are by you abused and set at naught; and the very roof which shelters you is desecrated with the marks of your irreverential contempt for all things human and divine. Would that—(and the wish is expressed more in sorrow than in anger)—would that your entire species were condensed into one enormous bluebottle, that we might crush you all at a single swoop!

Many, calling themselves philanthropists and Christians, have omitted to squash a fly when they had an opportunity of so doing; nay, some of these people have even been known to go the length of writing verses on the occasion, in which they applaud themselves for their own humane disposition, and congratulate the object of their mistaken mercy on its narrow escape from impending fate. There is nothing more wanting than to propose the establishment of a Royal Humane Society for the resuscitation of flies apparently drowned or suffocated. Can it possibly be imagined by the man who has succeeded after infinite pains in rescuing a greedy and intrusive insect from a gin-and-watery grave in his own vile potations, that he has thereby consulted the happiness of his fellow creatures, or promoted the cause of decency, cleanliness, good order, and domestic comfort? Let him watch the career of the mischievous little demon which he has thus been the means of restoring to the world, when he might have arrested its progress for ever. Observe the stout and respectable gentleman, loved, honoured, and esteemed in all the various relations of father, husband, friend, citizen, and Christian, who is on cushioned sofa composing himself for his wonted nap, after a dinner in substance and quantity of the most satisfactory description, and not untempered by a modicum of old port. His amiable partner, with that refined delicacy and sense of decorum peculiar to the female sex, has already withdrawn with her infant progeny, leaving her good man, as she fondly imagines, to enjoy the sweets of uninterrupted repose. At one moment we behold him slumbering softly as an infant—"so tranquil, helpless, stirless, and unmoved;" in the next, we remark with surprise sundry violent twitches and contortions of the limbs, as though the sleeper were under the operation of galvanism, or suffering from the pangs of a guilty conscience. Of what hidden crime does the memory thus agitate him—breaking in upon that rest which should steep the senses in forgetfulness of the world and its cares? On a sudden he starts from his couch with an appearance of frenzy!—his nostrils dilated, his eyes gleaming with immoderate excitation—an incipient curse quivering on his lips, and every vein swelling—every muscle tense with fearful and passionate energy of purpose. Is he possessed with a devil, or does he meditate suicide, that his manner is so wild and hurried? With impetuous velocity he rushes to the window, and beneath his vehement but futile strokes, aimed at a scarcely visible, and certainly impalpable object, the fragile glass flies into fragments, the source of future colds and curtain lectures without number. The immediate author of so much mischief, it is true, is the diminutive vampire which is now making its escape with cold-blooded indifference through a very considerable fracture in one of the panes; but surely the person who saved from destruction, and may thus be considered to have given existence to the cause of all this loss of temper and of property, cannot conscientiously affirm that his withers are unwrung! Mercy and forbearance are very great virtues when exercised with proper discretion; but man owes a paramount duty to society, with which none of the weaknesses, however amiable, of his nature should be allowed to interfere. It is no mercy to pardon and let loose upon the community one who, having already been convicted of manifold delinquencies, only waits a convenient season for adding to the catalogue of his crimes; and what is larceny, or felony, or even treason, compared with the perpetration of the outrages above attempted to be described?—We pause for a reply.

Summer is a most delectable—a most glorious season. We, who are fond of basking as a lizard, and whose inward spirit dances and exults like a very mote in the sun-beam, always hail its approach with rapture; but our anticipations of bright and serene days—of blue, cloudless, and transparent skies—of shadows the deeper from intensity of surrounding light—of yellow corn-fields, listless rambles, and lassitude rejoicing in green and sunny banks—are allayed by this one consideration, that

Waked by the summer ray, the reptile youngCome winged abroad. From every chinkAnd secret corner, where they slept awayThe wintry storms; by myriads forth at once,Swarming they pour.Go where you will, it is not possible to escape these "winged reptiles." They abound exceedingly in all sunny spots; nor in the shady lane do they not haunt every bush, and lie perdu under every leaf, thence sallying forth on the luckless wight who presumes to molest their "solitary reign;" they hang with deliberate importunity over the path of the sauntering pedestrian, and fly with the flying horseman, like the black cares (that is to say, blue devils) described by the Roman lyrist. Within doors they infest, harpy-like, the dinner-table—

Diripiuntque dapes, contactuque omnia foedantImmundo—and hover in impending clouds over the sugar basin at tea; in the pantry it is buz; in the dairy it is buz; in the kitchen it is buz; one loud, long-continued, and monotonous buz! Having little other occupation than that of propagating their species, the natural consequence, as we may learn from Mr. Malthus, is that their numbers increase in a frightfully progressive ratio from year to year; and it has at length become absolutely necessary that some decisive measures should be adopted to counteract the growing evil.

Upon the whole, he would not, perhaps, be considered to speak rashly or unadvisedly, who should affirm, that no earthly creature, of the same insignificant character and pretensions, is the agent of nearly so much mischief as the fly.—What a blessed order of things would immediately ensue, if every one of them was to be entirely swept away from the face of the earth! This most wished-for event, we fear, it will never be our lot to witness; but it may be permitted to a sincere patriot, in his benevolent and enthusiastic zeal for the well-being of his country, to indulge in aspirations that are tinged with a shade of extravagance. With respect, however, to the above mentioned vermin, the idea of their total annihilation may not be altogether chimerical. We know that the extirpation of wolves from England was accomplished by the commutation of an annual tribute for a certain number of their heads; and it is well worth the consideration of the legislature, whether, by adopting a somewhat similar principle, they may not rid the British dominions of an equally great and crying nuisance. The noble Duke, now at the head of his Majesty's Government, has it in his power to add another ray to his illustrious name, to secure the approbation and gratitude of all classes of the community, and to render his ministry for ever memorable, by the accomplishment of so desirable an object. In the mean time, let the Society of Arts offer their next large gold medal to the person who shall invent the most ingenious and destructive fly-trap. A certain quantity of quassia might be distributed gratis at Apothecaries' Hall, as vaccinatory matter is at the Cow-pox Hospital, with very considerable effect; and an act of parliament should be passed without delay, declaring the wilful destruction of a spider to be felony.—Blackwood's Magazine.

THE CORONATION OF INEZ DE CASTRO. 7

BY MRS. HEMANS"Tableau, aú l'Amour fait alliance avec la Tombe; union redoubtable de la mort et de la vie." MADAME DE STAEL.

There was music on the midnight;From a royal fane it roll'd,And a mighty bell, each pause between,Sternly and slowly toll'd.Strange was their mingling in the sky,It hush'd the listener's breath;For the music spoke of triumph high,The lonely bell, of death.There was hurrying through the midnight:—A sound of many feet;But they fell with a muffled fearfulness,Along the shadowy street;And softer, fainter, grew their tread,As it near'd the Minster-gate,Whence broad and solemn light was shedFrom a scene of royal state.Full glow'd the strong red radianceIn the centre of the nave,Where the folds of a purple canopySweep down in many a wave;Loading the marble pavement oldWith a weight of gorgeous gloom;For something lay 'midst their fretted gold,Like a shadow of the tomb.And within that rich pavilionHigh on a glittering throne,A woman's form sat silently,Midst the glare of light alone.Her Jewell'd robes fell strangely still—The drapery on her breastSeem'd with no pulse beneath to thrill,So stone-like was its rest.But a peal of lordly musicShook e'en the dust below,When the burning gold of the diademWas set on her pallid brow!Then died away that haughty sound,And from th' encircling band,Stept Prince and Chief, 'midst the hush profound,With homage to her hand.Why pass'd a faint cold shudderingOver each martial frame,As one by one, to touch that hand,Noble and leader came?Was not the settled aspect fair?Did not a queenly grace,Under the parted ebon hair.Sit on the pale still face?Death, Death! canst thou be lovelyUnto the eye of Life?Is not each pulse of the quick high breastWith thy cold mien at strife?—It was a strange and fearful sight,The crown upon that head,The glorious robes and the blaze of light,All gather'd round the Dead!And beside her stood in silenceOne with a brow as pale,And white lips rigidly compress'd,Lest the strong heart should fail;King Pedro with a jealous eyeWatching the homage doneBy the land's flower and chivalryTo her, his martyr'd one.But on the face he look'd notWhich once his star had been:To every form his glance was turn'd,Save of the breathless queen;Though something, won from the grare's embrace,Of her beauty still was there,Its hues were all of that shadowy place,'Twas not for him to bear.Alas! the crown, the sceptre,The treasures of the earth,And the priceless love that pour'd those gifts,Alike of wasted worth!The rites are closed—bear back the DeadUnto the chamber deep,Lay down again the royal head,Dust with the dust to sleep.There is music on the midnight—A requiem sad and slow.As the mourners through the sounding aisleIn dark procession go,And the ring of state, and the starry crown,And all the rich array,Are borne to the house of silence down,With her, that queen of clay.And tearlessly and firmly,King Pedro led the train—But his face was wrapt in his folding robe,When they lower'd the dust again.—'Tis hush'd at last, the tomb above,Hymns die, and steps depart:Who call'd thee strong as Death, O Love?Mightier thou wert and art!New Monthly Magazine.ART THOU THE MAID?

Art thou the maid from whose blue eyeMine drank such deep delight?Was thine that voice of melodyWhich charm'd the silent night?I fain would think thou art not sheWho hung upon mine arm,When love was yet a mystery,A sweet, resistless charm.It seemed to me as though the spellOn both alike were cast;I prayed but in thy sight to dwell,For thee, to breathe my last.Mine inmost secret soul was thine,Thou wert enthroned therein,Like sculptured saint in holy shrine,All free from guile and sin.And, heaven forgive! I did adoreWith more than pilgrim's zeal;And then thy smile–But oh! no more!No more may I reveal.Enough—we're parted–Both must ownThe accursed power of gold.I wander through the world alone;Thou hast been bought and sold.Blackwood's Magazine.It would be a very pleasant thing, if literary productions could be submitted to something like chemical analysis,—if we could separate the merit of a book, as we can the magnesia of Epsom salts, by a simple practical application of the doctrine of affinities.

The Gatherer

A snapper up of unconsidered trifles.SHAKSPEARE.A GOOD FELLOW

The secretary of a literary society being requested to draw up "a definition of a good fellow," applied to the members of the club, individually, for such hints as they could furnish, when, he received the following:—

Mr. Golightly.—A good fellow is one who rides blood horses, drives four-in-hand, speaks when he's spoken to, sings when he's asked, always turns his back on a dun, and never on a friend.

Mr. Le Blanc.—A good fellow is one who studies deep, reads trigonometry, and burns love songs; has a most cordial aversion for dancing and D'Egville, and would rather encounter a cannon than a fancy ball.

Hon. G. Montgomery.—A good fellow is one who abhors moralists and mathematics, and adores the classics and Caroline Mowbray.

Sir T. Wentworth.—A good fellow is one who attends the Fox-dinners, who goes to the Indies to purchase independence, and would rather encounter a buffalo than a boroughmonger.

Mr. M. Sterling.—A good fellow is a good neighbour, a good citizen, a good relation; in short, a good man.

Mr. M. Farlane.—A good fellow is a bonnie braw John Hielandman.

Mr. O'Connor.—A good fellow is one who talks loud and swears louder; cares little about learning, and less about his neckcloth; loves whiskey, patronizes bargemen, and wears nails in his shoes.

Mr. Musgrave.—A good fellow is prime—flash—and bang-up.

Mr. Burton.—A good fellow is one who knows "what's what," keeps accounts, and studies Cocker.

Mr. Rowley.—A good fellow likes turtle and cold punch, drinks Port when he can't get Champagne, and dines on mutton with Sir Robert, when he can't get venison at my lord's.

Mr. Lozell.—A good fellow is something compounded of the preceding.

Mr. Oakley.—A good fellow is something perfectly different from the preceding,—or Mr. Oakley is an ass.

MERCHANT TAILORS' SCHOOL

At Merchant Tailors' School, what timeOld Bishop held the rod,The boys rehearsed the old man's rhymeWhilst he would smile and nod.Apart I view'd a little childWho join'd not in the game:His face was what mammas call mildAnd fathers dull and tame.Pitying the boy, I thus address'dThe pedagogue of verse—"Why doth he not, Sir, like the rest,Your epigrams rehearse?""Sir!" answered thus the aged man,"He's not in Nature's debt;His ears so tight are seal'd, he can-Not learn his alphabet.""Why not?" I cried:—whereat to meHe spoke in minor clef—"He cannot learn his A, B, C,Because he's D, E, F."New Monthly Magazine.ROYAL LEARNING

The king of Persia made many inquiries of Sir Harford Jones respecting America, saying, "What sort of a place is it? How do you get at it? Is it underground, or how?"

COMPLIMENT MAL—APROPOS

Napoleon was once present at the performance of one of Pasiello's operas, in which was introduced an air by Cimarosa. Pasiello was in the box with the emperor, and received many compliments during the evening. At length, when the air by Cimarosa was played, the emperor turned round, and taking Pasiello by the hand, exclaimed, "By my faith, my friend, the man who has composed that air, may proclaim himself the greatest composer in Europe." "It is Cimarosa's," feebly articulated Pasiello. "I am sorry for it; but I cannot recall what I have said."

A gentleman taking an apartment, said to the landlady, "I assure you, madam, I never left a lodging but my landlady shed tears." She answered, "I hope it was not, Sir, because you went away without paying."

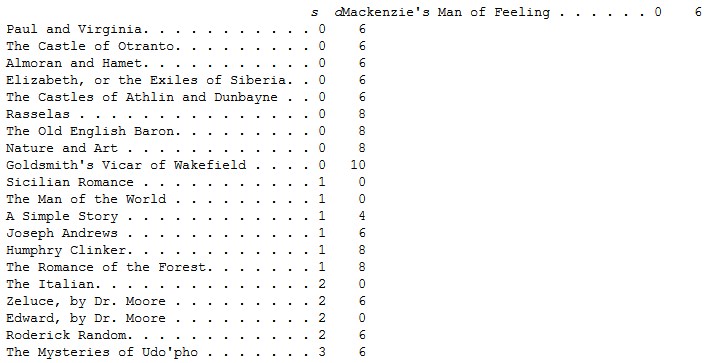

LOMBIRD'S EDITION OF THE Following Novels are already Published:

1

Scotorum cumulos flevit glacialis Ierne. CLAUDIAN.