полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 402, Supplementary Number (1829)

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 14, No. 402, Supplementary Number (1829)

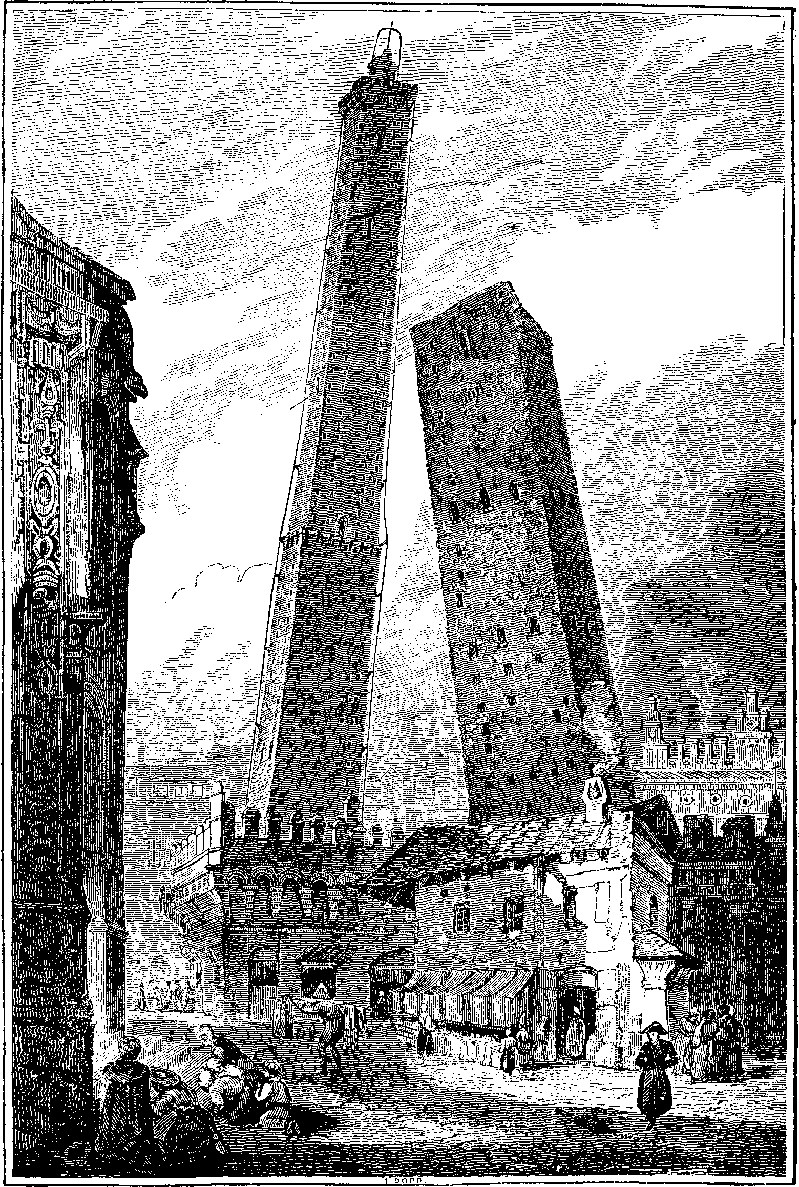

The Leaning Towers of Bologna

The Landscape Annual

LONDON AND PARIS, 1830MAGNIFIQUE! SUPERBE! will be the exclamation of the Parisians on beholding the Plates of this Work, at the Publishers, in the Gallerie Vivienne, and equally enthusiastic will be the admiration of all Londoners whilst inspecting them in Cheapside. The second title, "The Tourist in Italy and Switzerland," implies the contents of the volume far better than the first. There are twenty-five Plates, each nearly as large as one of our pages, by various engravers, and all from drawings, by Mr. Prout. The subjects are as follow:—Geneva, Lausanne, Chillon, Bridge of St. Maurice, Lavey, Martigny, Sion, Visp, Domo d'Ossola, Castle of Anghiera, Milan Cathedral, Lake of Como, Como, Verona, Vicenza, Padua, Petrarch's House at Arqua, the Rialto at Venice, Ducal Palace at ditto, Palace of the Two Foscari, ditto; Bridge of Sighs, ditto; Old Ducal Palace at Ferrara, Bologna, Ponte Sisto, Rome, Fish Market, Ruins, ditto, and a Vignette of Constantine's Arch.

The Descriptions are from the elegant pen of Thomas Roscoe, Esq. By permission, of the proprietor we have selected one of the plates, and a portion of its accompanying description.

BOLOGNA,"Celebrated alike in arts and in letters, Bologna, 'the mother of studies,' presents numerous objects of interest to the amateur and to the scholar. The halls which were trod by Lanfranc and Irnerius, and the ceilings which glow with the colours of Guido and the Carracci, can never be neglected by any to whom learning and taste are dear.

"The external appearance of Bologna is singular and striking. The principal streets display lofty arcades, and the churches, which are very numerous, confer upon the city a highly architectural character. But the most remarkable edifices in Bologna are the watch-towers, represented in the engraving. During the twelfth century, when the cities of Italy, 'tutte piene di tirranni,' were rivals in arms as afterwards in arts, watch-towers of considerable elevation were frequently erected. In Venice, in Pisa, in Cremona, in Modena, and in Florence these singular structures yet remain; but none are more remarkable than the towers of the Asinelli and Garisenda in Bologna. The former, according to one chronicler, was built in 1109, while other authorities assign it to the year 1119. The Garisenda tower, constructed a few years later, has been immortalized in the verse of Dante.

"When the poet and his guide are snatched up by the huge Antaeus, the bard compares the stooping stature of the giant to the tower of the Garisenda, which, as the spectator stands at its base while the clouds are sailing from the quarter to which it inclines, appears to be falling upon his head,

"'As appearsThe tower of Cariaenda from beneathWhere it doth lean, if chance a passing cloudSo sail across that opposite it hangs;Such then Antaeus seem'd, as at mine easeI mark'd him stooping.'"The tower of the Asinelli rises the height of about 350 feet, and is said to be three feet and a half out of the perpendicular. The adventurous traveller may ascend to the top by a laborious staircase of 500 steps. Those steps were trod by the late amiable and excellent Sir James Edward Smith, who has described the view presented at the summit. 'The day was unfavourable for a view; but we could well distinguish Imola, Ferrara and Modena, as well as the hills about Verona, Mount Baldus, &c., seeming to rise abruptly from the dead flat which extends on three sides of Bologna. On the south are some very pleasant hills stuck with villas.' The Garisenda tower, erected probably by the family of the Garidendi, is about 130 feet in height, and inclines as much as eight feet from the perpendicular. It has been conjectured that these towers were originally constructed as they now appear; but it is difficult to give credit to such a supposition.

"According to Montfaucon, the celebrated antiquary, the leaning of these towers has been occasioned by the sinking of the earth. 'We several times observed the tower called Asinelli, and the other near it, named Garisenda. The latter of them stoops so much that a perpendicular, let fall from the top, will be seven feet from the bottom of it; and, as appears upon examination, when this tower bowed, a great part of it went to ruin, because the ground that side that inclined stood on was not so firm as the other, which may be said of all other towers that lean so; for besides these two here mentioned, the tower for the bells of St. Mary Zobenica, at Venice, leans considerably to one side. So also at Ravenna, I took notice of another stooping tower occasioned by the ground on that side giving way a little. In the way from Ferrara to Venice, where the soil is marshy, we see a structure of great antiquity leaning to one side. We might easily produce other instances of this nature. When the whole structure of the Garisenda stooped, much of it fell, as appears by the top of it.

"Bologna, like most of the cities of Italy, has been the seat of many tragical incidents, affording such rich materials for her novelists. Amongst others, is one which we give in the words of the excellent critic by whom it is related. 'The family Geremie of Bologna were at the head of the Guelphs, and that of the Lambertazzi of the Ghibbelines, who formed an opposition by no means despicable to the domineering party. Bonifazio Geremei and Imelda Lambertazzi, forgetting the feuds of their families, fell passionately in love with each other, and Imelda received her lover into her house. This coming to her brothers' knowledge, they rushed into the room where the two lovers were, and Imelda could scarcely escape, whilst one of the brothers plunged a dagger, poisoned after the Saracen fashion, into Bonifazio's breast, whose body was thrown into some concealed part of the house and covered with rubbish. Imelda hastened to him, following the tracks of his blood, as soon as the brothers were gone; found him, and supposing him not quite dead, generously, as our own Queen Eleanor had done about the same time, sucked the poison from the bleeding wound, the only remedy which could possibly save his life; but it was too late: Imelda's attendants found her a corpse, embracing that of her beloved Bonifazio.'"

The success of the Landscape Annual is very far from problematical. All our travelled nobility and people of fortune will buy it to refresh their acquaintance with the beautiful scenes it includes; and it is hardly possible to imagine a more agreeable book-companion on the journey itself.

LITERARY SOUVENIR

(Concluded from Supplement, page 336.)

The poetry of the Souvenir is, as usual, for the most part excellent. Among the best pieces are The Dying Mother to her Infant, by Caroline Bowles; Bring back the chain, by the authoress of the "Sorrows of Rosalie;" and The Birth-day, by N.P. Willis, a popular American writer. There are likewise some very graceful and touching pieces by Mr. Watts, the editor, one of which will be found in our next number. There are too some pleasant attempts at humorous relief; but "Vanity Fair" is a very poor attempt at jingling rhyme. We quote one of these light pieces for the sake of adding variety to our sheet:

WHERE IS MISS MYRTLE?

AIR—Sweet Kitty CloverWhere is Miss Myrtle? can any one tell?Where is she gone, where is she gone?She flirts with another, I know very well;And I—am left all alone!She flies to the window when Arundel rings:She's all over smiles when Lord Archibald sings;It's plain that her Cupid has two pair of wings;Where is she gone, where is she gone?Her love and my love are different things:And I—am left all alone!I brought her, one morning, a rose for her browWhere is she gone, where is she gone?She told me such horrors were never worn now:And I—am left all alone!But I saw her at night with a rose in her hair,And I guess who it came from,—of course I don't care!We all know that girls are as false us they're fair;Where is she gone, where is she gone?I'm sure the lieutenant's a horrible bear;And I—am left all alone!Whenever we go on the Downs for a ride,Where is she gone, where is she gone?She looks for another to trot by her side:And I—am left all alone!And whenever I take her down stairs from a ball,She nods to some puppy to put on her shawl:I'm a peaceable man, and I don't like a brawl:Where is she gone, where is she gone?But I would give a trifle to horsewhip them all:And I—am left all alone!She tells me her mother belongs to the sect,Where is she gone, where is she gone?Which holds that all waltzing is quite incorrect:And I—am left all alone!But a fire's in my heart and a fire's in my brain,When she waltzes away with Sir Phelim O'Shane;I don't think I ever can ask her again:Where is she gone, where is she gone?And, lord! since the summer she's grown very plain,And I—am left all alone!She said that she liked me a twelvemonth ago!Where is she gone, where is she gone?And how should I guess that she'd torture me so!And I—am left all alone!Some day she'll find out it was not very wiseTo laugh at the breath of a true lover's sighs:After all, Fanny Myrtle is not such a prize;Where is she gone, where is she gone?Louisa Dalrymple has exquisite eyes:And I'll be—no longer alone!Mr. Praed has an exquisite poem, "Memory;" and we had nearly passed by a song by Mr. T. Moore.

Alone beneath the moon I roved,And thought how oft in hours gone by,I heard my Mary say she lovedTo look upon a moonlight sky!The day had been one lengthened shower,Till moonlight came, with lustre meek,To light up every weeping flower,Like smiles upon a mourner's cheek.I called to mind from Eastern booksA thought that could not leave me soon:—"The moon on many a night-flower looks,The night-flower sees no other moon."And thus I thought our fortune's run,For many a lover sighs to thee;While oh! I feel there is but one,One Mary in the world for me!The illustrations are almost unexceptionably good; the gems in this way being Mrs. Siddons, as Lady Macbeth, by C. Rolls, after Harlowe: the face is perhaps the most intellectual piece of engraving ever seen; the sublime effect in so small a space is truly surprising. A Portrait, by W. Danforth, after Leslie, ranks next; and the beauty and variety of the remainder of the prints are so great as to prevent our individualizing them to the reader. Taken altogether, they form one of the finest Annual Galleries or Collections.

THE KEEPSAKE

Without going into a dreamy discussion on the literature of this work, we venture to say it has rather retrograded from, than improved upon the volume of last year. Great and titled names only furnish the gilt: and this fact is now so generally understood, that readers are no longer deceived by them, in the quality of the gingerbread. Mr. Watts is so convinced of this fact, that he has given the cut direct to many titled authors; and, for aught we know, he has produced as good a volume this year as on any former occasion. The proprietor of the Keepsake appears to think otherwise; and his editor has accordingly produced a book of very meagre interest, though of mightier pretensions than his rivals. Months ago we were told by announcement, paragraph and advertisement, of a tragedy, The House of Aspen, by Sir Walter Scott, which now turns out to be as dull an affair as any known in these days of dramatic poverty and theatrical ups and downs. Sir Walter, in an advertisement of great modesty, dated April 1, says, that "being of too small a size of consequence for a separate publication, the piece is sent as a contribution to the Keepsake, where its demerits may be hidden amid the beauties of more valuable articles." The piece has been adapted to a minor stage with some effect, but nothing higher than a melodrama. We have neither room nor inclination to extract a scene, but one of the metrical pieces has tempted us:—

Sweet shone the sun on the fair Lake of Toro,Weak were the whispers that waved the dark wood,As a fair maiden bewilder'd in sorrow,Sigh'd to the breezes and wept to the flood."Saints from the mansion of bliss lowly bending,Virgin, that hear'st the poor suppliant's cry,Grant my petition, in anguish ascending.My Frederick restore, or let Eleanor die."Distant and faint were the sounds of the battle,With the breezes they rise, with the breezes they fail,Till the shout, and the groan, and the conflict's dread rattle,And the chase's wild clamour came loading the gale.Breathless she gaz'd through the woodland so dreary,Slowly approaching, a warrior was seen;Life's ebbing tide mark'd his footstep so weary,Cleft was his helmet, and woe was his mien."Save thee, fair maid, for our armies are flying;Save thee, fair maid, for thy guardian is low;Cold on yon heath thy bold Frederick is lying,Fast through the woodland approaches the foe."Two of the best stories are The Bride, by Theodore Hook, and the Shooting Star, an Irish tale, by Lord Nugent; and a Dialogue for the year 2310, by the author of Granby, has considerable smartness. The scene is in London, where one of the speakers has just arrived "from out of Scotland; breakfasted this morning at Edinburgh, and have not been in town above a couple of hours. The roads are dreadfully heavy now: conceive my having been seven hours and a half coming from Edinburgh to London." Killing between four and five thousand head of game in one day is shooting ill; and one of the party has a gun which would give twenty-seven discharges in a minute, and mine would give only twenty-five. I really must change my maker. Have you seen the last new invention, the hydro-potassian lock?" Hunting machines, that would fly like balloons over a ten-foot wall—A candidate for the Circumnavigation Club, who has been four times round the world in his own, yacht—A point of bad taste to make a morning call by daylight—Dining at twelve P.M.—A spring-door with a self-acting knocker, which gives a treble knock, and is opened by a steam porter in livery—A chair mounting from the hall, through the ceiling, into the drawing room—Talking to a lady two miles off through a telescope, till one's fingers ache—A callisthenic academy for the children of pauper operatives—An automaton note-writer—A lady professing ignorance of Almack's, "a club where Swift and Johnson used to meet, but I don't profess to be an antiquarian"—"Love and Algebra," one of the common scientific novels thumbed by coal-heavers and orange-women, very well for the common people—Every thing is taught them now by means of scientific novels: such as "Geological Atoms, or the Adventures of a Dustman"—Doubted very much whether English wheat is fit for any thing but the brute creation—Dark times of the 19th century—Six-hourly and half-daily newspapers—"apropos, as the hackney-coachmen say"—Turkey, one of the southern provinces of Russia—His Majesty Jonathan III. of Washington—The Emperor of India—The Burmese Republic—English the language of three-fourths of Asia, nine-tenths of North America, half Africa, and all the insular states in the South Seas—and England, that little kingdom, with a population of not more than forty millions, has had the honour of colonizing half the globe; but "these countries are our colonies no longer." Such are a few of the wonders of 2130! In the Dialogue is an admirable joke with a scientific street-sweeper and a learned beggar, who pleads necessitas non habet legem, and "embraces the profession of an operative mendicant." But here is a morceau:

Lady D.—Ah! Lord A.! Mr. C.! most unexpected persons both! I heard only yesterday that one of you was in Greenland, and the other in Africa. What false reports they circulate!

Lord A.—The reports were true not long ago, and I believe we returned about the same time. You, Lady D., have been also travelling, I believe.

Lady D.—Yes, we were out of England in the winter. Our physician commanded a warmer climate for Lord D. so we took a villa on the Niger, and afterwards spent a short time at Sackatoo.

Mr. C.—I suppose you found it full of English?

Lady D.—Oh, quite full—and such a set! We knew hardly any of them. In fact, we did not go there for society. We met a few pleasant people, Australians; the Abershaws, the Hardy Vauxes, and Sir William and Lady Soames.

Mr. C.—Did you go by the new Tangier and Timbuctoo road?

Lady D.—Yes, we did, and we found it excellent. By the bye, Lord A., to digress to a different latitude, how did you succeed in your last excursion to the North Pole?

Lord A.—To tell you the truth, extremely ill; we had most improvidently taken with us scarcely enough of the solvent to work our way through the ice, and our concentrated essence of caloric was found to be of a very inferior quality. I shall try again next summer.

Lady D.—I believe we shall go to Spitzbergen ourselves.

Lord A.—I am happy to think that, in that case, I may perhaps have the pleasure of meeting you there on my return. I must go to the Pole, by the way of North Georgia: I am engaged to visit an Eskimaux friend.

Still more ludicrous are the following historical blunders:—One of the party asks how Napoleon is introduced in an historical novel of 1830? The reply is—"He and the Emperor Alexander of Russia are introduced dining with the King at Brighton. Napoleon quarrels with the two sovereigns, and challenges them to a personal encounter. Each claims the right of fighting by deputy. The King of England appoints his prime minister, the Duke of Wellington; the Emperor Alexander appoints Prince Kutusoff. The Duke of Wellington is to go out first, and is to meet Napoleon at Battersea Fields. There were open fields at Battersea: then: only think! open fields! I don't know how the duel ends—I am just in the midst of it—it is so interesting."

The author of Anastasius (Mr. Thos. Hope) has contributed five or six pages on Self-love, Sympathy, and Selfishness—which are deep enough for any Lady D. of this or the next century. We expected a powerful and picturesque tale of the East, and not such sententious matter as this:—"Every sentient entity, from the lowest of brutes to the highest of human beings, desires self-gratification:" we may add, a principle as well understood in Covent-garden as in Portland-place. Mr. Banim has written The Hall of the Castle, an interesting Irish story; and Lord Normanby, The Prophet of St. Paul's, of the date of 1514—which concludes the volume.

Among the Poetry are some pretty verses by Lord Porchester; but it is well that metrical pieces do not predominate, for some of the writers are sadly unmusical sonneteers.

The "Letters from Lord Byron to several Friends" are not of interest enough for the space they occupy.

The Plates are beyond praise. The Frontispiece Portrait of Lady Georgiana Agar Ellis, by Charles Heath, is one of the most exquisite ever engraved; and two plates illustrating Sir Walter Scott's House of Aspen have the effect of beautiful pictures on a blank wall. Two views of Virginia Water are, perhaps, questionable in the same volume; but they are admirably engraved. Wilkie's "beautiful, though," as Lord Normanby says, "somewhat slight cabinet picture of the Princess Doria and the Pilgrims1" has been finely executed by Heath; and a View of Venice, from a drawing by Prout, is a masterpiece of Freebairne. Equal to either of these is The Faithful Servant, engraved by Goodyear, after Cooper, and Dorothea, the title-page plate. Of The Bride, engraved by Charles Heath, from a picture by Leslie, it is impossible to speak in terms of sufficient praise, as it is, without exception, one of the loveliest prints ever beheld. We have had our laugh at The Portrait, a scene from Foote, painted by Smirke, and engraved by Portbury. Its whim and humour is describable only by the British Aristophanes. We can only add, that it is Lady Pentweazle sitting to Carmine for her portrait—the look that he despairs of imitating, as we do Foote's account of her family:—

"All my family, by the mother's side, are famous for their eyes. I have a great aunt amongst the beauties at Windsor; she has a sister at Hampton Court, a perdegeous fine woman! she had but one eye, but that was a piercer: that one eye got her three husbands."

The painter appears to us to be a portrait of Foote. We ought not to forget to mention, at least, Francis I. and his Sister, splendidly engraved by C. Heath, from a picture by Bonington.

THE COMIC ANNUAL

We intend to let the facetious author have his own say on the comical contents of this very comical little work, by merely running over a few of the head and tail pieces of the several pages. We think with Mr. Hood, that "In the Christmas Holidays, or rather, Holly Days, according to one of the emblems of the season, we naturally look for mirth. Christmas is strictly a Comic Annual, and its specific gaiety is even implied in the specific gravity of its oxen." So much for the design, which is far more congenial to our feelings than the thousand and one sonnets, pointless epigrams, laments, and monodies, which are usually showered from crimson and gold envelopes at this dull season of the year. There are thirty-seven pieces—all in humorous and "righte merrie conceite." We shall give a few random extracts, or specimens, and then run over the cuts. Our first is—(and what should it be?)

NUMBER ONE

"It's very hard! and so it is,To live in such a row,And witness this, that every MissBut me has got a beau.For Love goes calling up and down,But here he seems to shun.I'm sure he has been asked enoughTo call at Number One!"I'm sick of all the double knocksThat come to Number Four!At Number Three I often seeA lover at the door;And one in blue, at Number Two,Calls daily like a dun,—It's very hard they come so nearAnd not at Number One."Miss Bell, I hear, has got a dearExactly to her mind,By sitting at the window paneWithout a bit of blind;But I go in the balcony,Which she has never done,Yet arts that thrive at Number FiveDon't take at Number One."'Tis hard with plenty in the street,And plenty passing by,—There's nice young men at Number Ten,But only rather shy;And Mrs. Smith across the wayHas got a grown-up son.But la! he hardly seems to knowThere is a Number One!"There's Mr. Wick at Number Nine,But he's intent on pelf,And though he's pious, will not loveHis neighbour as himself.At Number Seven there was a sale—The goods had quite a run!And here I've got my single lotOn hand at Number One!"My mother often sits at workAnd talks of props and stays,And what a comfort I shall beIn her declining days!The very maids about the houseHave set me down a nun,The sweethearts all belong to themThat call at Number One!"Once only, when the flue took fire,One Friday afternoon,Young Mr. Long came kindly in,And told me not to swoon.Why can't he come again withoutThe Phoenix and the Sun?We cannot always have a flueOn fire at Number One!"I am not old, I am not plain,Nor awkward in my gait—I am not crooked like the brideThat went from Number Eight;I'm sure white satin made her lookAs brown as any bun—But even beauty has no chanceI think at Number One."At Number Six they say Miss RoseHas slain a score of hearts,And Cupid, for her sake, has beenQuite prodigal of darts.The imp they show with bended bow—I wish he had a gun;But if he had, he'd never deignTo shoot with Number One."It's very hard, and so it is,To live in such a row;And here's a ballad-singer comeTo aggravate my woe;O take away your foolish songAnd tones enough to stun—There is 'nae luck about the house,'I know at Number One."Next is a prose sketch:

THE FURLOUGH.—AN IRISH ANECDOTE

"In the autumn of 1825, some private affairs called me into the sister kingdom; and as I did not travel, like Polyphemus, with my eye out, I gathered a few samples of Irish character, amongst which was the following incident:—

"I was standing one morning at the window of 'mine Inn,' when my attention was attracted by a scene that took place beneath. The Belfast coach was standing at the door, and on the roof, in front, sat a solitary outside passenger, a fine young fellow, in the uniform of the Connaught Rangers. Below, by the front wheel, stood an old woman, seemingly his mother, a young man, and a younger woman, sister or sweetheart; and they were all earnestly entreating the young soldier to descend from his seat on the coach.