полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 532, February 4, 1832

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 19, No. 532, February 4, 1832

CAVERN OF ROBERT THE DEVIL.

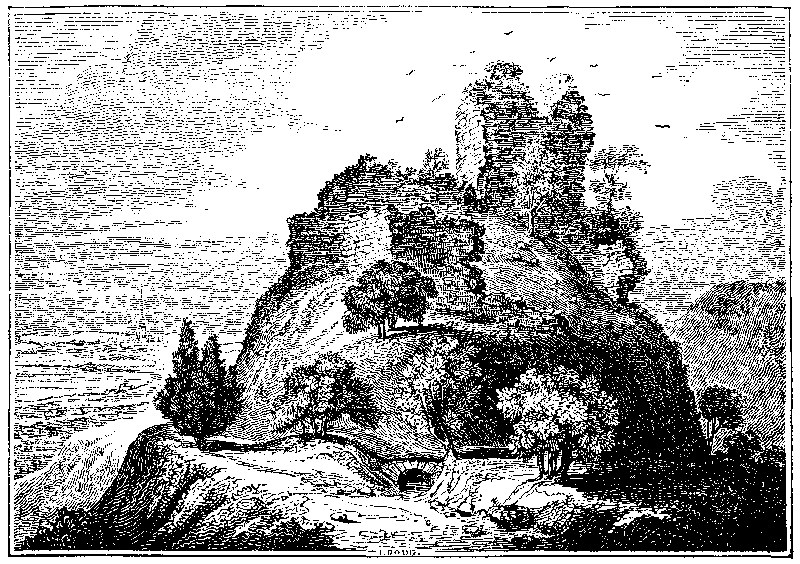

CASTLE OF ROBERT THE DEVIL.

ROBERT THE DEVIL

All the town, and the country too, by paragraph circumstantial, and puff direct, must have learned that every theatre in this Metropolis, and consequently, every stage in the country, is to have its version of the splendid French opera Robert le Diable. Its success in Paris has been what the good folks there call magnifique, and playing the devil has been the theatrical order of day and night since the Revolution. As we know nothing of its merits, and do not write of what we neither see nor hear, nor believe any report of, we do not put up our hopes for its success. But, as the story of the opera is a pretty piece of Norman romance, some fair penciller has sent us the sketches of the annexed cuts, and our Engraver has thus pitted himself with Grieve, Stanfield, Roberts, and scores of minor scene-painters, who are building canvass castles, and scooping out caverns for the King's Theatre, Covent Garden, and Drury Lane Theatres. Theirs will be but candle-light glories: our scenes will be the same by all lights. But as scenes are of little use without actors, and cuts of less worth without description, we append our fair Correspondent's historical notices of the sites and the dram. pers. of "this our tragedy."

CASTLE OF ROBERT LE DIABLE, OR ROBERT THE DEVIL

The founder of this ancient castle bears the name of Robert the Devil. It is a wonderful relic of old Norman fortification, being so defended by nature, as to bid defiance to its enemies, and could only have fallen by stratagem. It is situated on the left side of the River Seine and in the province of Normandy. The subterranean caverns by their amazing extent sufficiently attest the ancient importance of this structure; tradition says they extend to the banks of the Seine. Its antiquity is fully proved by some of the architectural fragments bearing the stamp of 912. On arriving at the summit of the mountain, the tourist receives an impression like enchantment: the castle seems to have been conveyed there by fairies; and at the base the eye is charmed by the fine and picturesque forest of Bourgtheroulde: villages elegantly grouped, enrich with their beautiful fabrics each bank of the Seine which majestically traverses a luxurious landscape. Romance, fable, and the tradition of shepherds and peasants describe Robert the Devil as Governor of Neustria, and a descendent of Rollo the celebrated Norman chief, whose name was changed to Robert, Duke of Normandy in 923, on his marriage with the daughter of Charles the simple, King of France. His great and valiant achievements are remembered in that country so renowned by his race, and where his name still awakens every sentiment of superstitious awe. All in the environs of the castle recount his wonderful and warlike exploits; his numerous amours; and his rigid penitence by which he hoped to appease the wrath of offended Heaven. The moans of his victims are said to resound in the Northern subterranean caverns; the peasantry also believe that the spirit of Robert is condemned to haunt the ruins of his castle, and the tombs of his "Ladies Fair." In justice to his memory be it remembered, that his acts of cruelty were alone aimed at the rapacious and guilty, and that in him helpless innocence ever found a protector.

Robert the Devil was cotemporary with our Danish King Harold, 1065; he assisted Henry, the eldest son of Robert of Normandy, in gaining possession of the crown, and accompanied him with a large army into the capital of France, where they ravaged the territory of the rebels, by burning the towns and villages, and putting the inhabitants to the sword: on this account he was called Robert the Devil.

When tranquillity was restored, and Henry freed from his enemies, Robert made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land with other powerful potentates. On his return he was taken ill, and appointed an illegitimate son his successor, whose mother was the daughter of a dealer in skins at Falaise, and this son became that celebrated William of Normandy, our renowned conqueror! The Normans instigated the people to reject him, on the plea of his illegitimacy; but Henry I., then King of France, gratefully remembered the good offices of Robert the Devil, William's Father: therefore espoused his cause, and raised an army of three thousand men to invade Normandy; long and obstinate wars continued, which did not terminate till William had accomplished the successful invasion of England; he was the grandson of Rollo, known after his marriage as Robert the 1st., Duke of Normandy, who died 935. Thus from one of his numerous amours sprung our new dynasty of kings, which totally changed the aspect of the times. By some historians he is called Robert the IInd., Duke of Normandy, but the name by which he is generally known, is that dignified one of William the Conqueror.

CAVERN OF ROBERT LE DIABLE

The remains of this cavern (situated in Normandy) command the attention of the lovers of history, not only from its antiquity, but also from its gloomy recesses, having afforded a safe shelter to our weak and cruel King John. Here he bade farewell to this province which he abandoned to the French Knights, and from whom he carefully concealed every trace of his retreat. The entrance is almost obscured, and tradition says it is so artfully managed as to have the appearance of a passage to another. The spot is barren, and it appears as if a thunder-bolt had burnt up the verdure. The spirit of Robert le Diable is supposed to haunt the cavern in the form of a wolf, and advances uttering piteous cries, and steadfastly gazing on its place of defence (the caverns extending to the River Seine) reviews his former glory and conquests, and seems bitterly to lament the present decay. In vain the peasants commence the chase; they assert that the wolf though closely pursued always eludes the vigilance of the huntsman. On the death of Richard I. of England, 1199, his Brother John was proclaimed King of Normandy and Aquitaine; the Duchies of Brittany, the Counties of Anjou, Maine, Tours and others, acknowledged Arthur, John's nephew, as their sovereign, and claimed the protection of the King of France, Philip II., surnamed Augustus; but he despairing of being able to retain these provinces against the will of their inhabitants, sacrificed Arthur and his followers to John, who in a skirmish with some of the Norman Lords, carried them all prisoners into Normandy, where Arthur soon disappeared: the Britons assert that he was murdered by his uncle; and the Normans that he was accidentally killed in endeavouring to escape. The death of their favourite Prince stung the Britons to madness, as in him centered their last hope of regaining independence: an ardent imagination led them to believe their future destiny connected with this child, which inspired them with a wild affection for Philip, as being the enemy of his murderer. They accused John before the French King of Arthur's murder, and he was summoned as a Vassal of Normandy to appear and defend himself before the twelve Peers of France. This command being treated with contempt, the lands John held under the French crown were declared forfeit, and an army levied to put it into execution. It was on this emergency that John found a safe place of concealment in the cavern of Robert the Devil.

LACONICS, &c

Continued from page 53.)Generosity is not the virtue of the multitude, and for this reason: selfishness is often the consequence of ignorance, and it requires a cultivated mind to discern where the rights of others interfere with our own wishes.

If commerce has benefited, it has also injured the human race; and the invention of the compass has brought disease as well as wealth in its train.

The days of joy are as long and perhaps as frequent as those of grief; but either the memory is treacherous or the mind is too morbid to admit this to be the case.

Without occasional seriousness and even melancholy, mirth loses its magic, and pleasure becomes unpalatable.

It is unlucky that experience being our best teacher, we have only learnt its lessons perfectly, when we no longer stand in need of them; and have provided ourselves armour we can never wear.

Chastity in women may be said to arise more from attention to worldly motives than deference to moral obligation: there is not so much continence amongst men, because there is not the same restriction.

A resolution to put up calmly with misfortune, invariably has the effect of lightening the load.

Conceit is usually seen during our first investigations after knowledge; but time and more accurate research teach us that not only is our comprehension limited, but knowledge itself is so imperfect, as not to warrant any vanity upon it at all.

Extravagance is of course merely comparative: a man may be a spendthrift in copper as well as gold.

We had rather be made acquainted at any time with the reality and certainty of distress, than be tortured by the feverish and restless anxiety of doubt.

A too great nicety about diet is being over scrupulous, and is converting moderation into a fault; but on the other hand it is little better than gluttony, if we cannot refrain from what may by possibility be even slightly injurious.

A celebrated traveller who had been twice round the world and visited every remarkable country, declared, that thought he had seen many wonderful things, he had never chanced to see a handsome old woman.

It is difficult enough to persuade a tool, but persuasion is not all the difficulty: obstinacy still remains to be brought under subjection.

A prejudiced person is universally condemned and yet many of our prejudices are excusable, and some of them necessary: if we do not indulge a few of our prejudices, we shall have to go on doubting and inquiring for ever.

Scepticism has ever been the bugbear of youthful vanity, and it is considered knowing to quarrel with existing institutions and established truths; our experienced reflection regrets this inclination and we become weary of distracting ourselves with endless difficulties.

In dreaming, it is remarkable how easily and yet imperceptibly the mind connects events altogether differing in their nature; and if we hear any noise during sleep, how instantaneously the sound is woven in with the events of our dream and as satisfactorily accounted.

The unpleasant sensation that is produced by modesty, is amply compensated by the prepossession it creates in our favour.

Public virtue prospers by the vices of individuals. The spendthrift gives a circulation to the coin of the realm, while the miser is equally useful in gleaning and scraping together what others have too profusely scattered. Luxury gives a livelihood to thousands, and the numbers supported by vanity are beyond calculation.

There is a distinction to be drawn between self-love and selfishness, though they are usually confounded. Self-love is the effect of instinct, and is necessary for our preservation in common with other animals; but selfishness is a mental defect and is generated by narrowness of soul.

The difference between honour and honesty is this: honour is dictated by a regard to character, honesty arises from a feeling of duty.

It is difficult to avoid envy without laying ourselves open to contempt; for in being too scrupulous not to trespass on others we lay ourselves open to be trifled with and trampled on.

That "familiarity breeds contempt" does not only mean, that he who is too familiar with us incurs our contempt; but also that novelty being indispensably necessary to our happiness we cease to admire what habit has familiarized.

Poverty, like every thing else has its fair side. The poor man has the gratification of knowing that no one can have any interest in his death; and in his intercourse with the world he can be certain that wherever he is welcome, it is exclusively on his own account.

If the poor have but few comforts, they are free from many miseries, mental as well as personal, that their superiors are subjected to: they have no physicians who live by their sufferings, and they never experience the curse of sensibility.

Eloquence, engaging as it is, must always be regarded with suspicion. The great use made of it in the history of literature, has been to mislead the head by an appeal to the heart, and it was for this reason the Athenians forbid their orators the use of it.

Conceit is generally proportionate with high station, and the greatest geniuses have not been entirely free from it: what indeed is ambition but an immoderate love of praise?

When we call to mind the humiliating necessities of human nature as far as the body is concerned, and in our intellectual resolves the meanness or paltriness of many of our motives to action, we may well be surprised that man who has so much cause to be humble should indulge for a moment in pride.

It is not so easy as philosophers tell us to lay aside our prejudices; mere volition cannot enable us to divest ourselves of long established feelings, and even reason is averse to laying aside theories it has once been taught to admire.

A man may start at impending danger or wince at the sensation of pain: and yet he may be a true philosopher and not be afraid of death.

The epicure, the drunkard, and the man of loose morals are equally contemptible: though the brutes obey instinct, they never exceed the bounds of moderation; and besides, it is beneath the dignity of man to place felicity in the service of his senses.

A passionate man should be regarded with the same caution as a loaded blunderbuss, which may unexpectedly go off and do us an injury.

There are many fools in the world and few wise men; at any rate there are more false than sound reasoners; wherefore it would seem more politic to adopt the opinion of the minority on most occasions.

Those who are deficient in any particular accomplishment usually contrive either openly or indirectly to express their contempt for it: thus removing that obstacle which removes them from the same level.

(To be concluded in our next.)

TRANSLATION OF DELLA CASA'S SONNET TO THE CITY OF VENICE

(For the Mirror.)Where these rich palaces and stately pilesNow rear their marble fronts, in sculptur'd pride,Stood once a few rude scatter'd huts, besideThe desert shores of some poor clust'ring isles.Yet here a hardy band, from vices free,In fragile barks, rode fearless o'er the sea:Not seeking over provinces to stride,But here to dwell, afar from slavery.They knew not fierce ambition's lust of power,And while their hearts were free from thirst of gold,Rather than falsehood—death they would behold.If heaven hath granted thee a mightier dower,I honour not the fruits that spring from theeWith thy new riches:—Death and Tyranny.E.L.J.THE HOUSE OF UNDER

(For the Mirror.)There are few families more ancient, more generally known, or more widely diffused throughout the known world, than that of Under: indeed, in every nation, though bearing different names, some branch of this family is extant; and there is no doubt that the Dessous of France, the Unters of Germany, and the Onders of the Land-under-water, belong to the same ancient and venerable house. The founders of the house, however, were of low origin, and generally down in the world. Undergo was the job of the family, as patient as a lamb: he encouraged the blessed martyrs in times of yore, and is still in existence, though his patience has somewhat diminished. Underhand is a far different character to the preceding, a double-dealing rascal, and as sly as a fox; he greets you with a smiling countenance, and while one hand is employed in shaking yours, he is disembarrassing you of the contents of your pocket with the other. Underline is a gentleman of some literary attainments, though not entirely divested of quackery; he is particularly noted for the emphasis he gives to certain points in his discourse, and though in some cases, perhaps, he is a little too prodigal of this kind of effect, yet we could not well do without him. Undermine is a greater rascal than Underhand, and had it not been for the counter-acting influence of Underproof, our house had fallen to the ground; to the ground it might have fallen, but had it gone farther, it would have been only to be revived in the person of Underground, a gentleman well known in the kitchens and pantries of the metropolis, the pantries in particular, he being a constant companion to the Under-butler. Understand is the pride of the house, and by his shining qualities, has raised himself to an eminence never reached by any other member of the family. He is a conspicuous exception to the downcast looks of so many of his relations. Undertake is an enterprising fellow, but he is often deceived and fails in his schemes; not so Undertaker, (whose similarity in name would make some folks believe there was some connexion;) no, his affairs are calculated to a wonderful nicety, and every tear is priced. Underwriter is a speculative genius, and—but the less we say of him the better. Underrate is a character I cannot avoid mentioning, though I wish with all my heart he was dead: his greatest pleasure consists in detracting from the good qualities of his neighbours.

I have only mentioned the English part of "Our House," although there are even some of that branch, whom I cannot at present call to mind, except Underdone, a lover of raw beef-steaks, and Undervalue, a person who has proved himself a great friend to custom-house officers, having some of the cunning of Underhand, but not quite so much luck, and subjecting his goods to seizure, for having tried to cheat the king. But I must leave this subject, and take my leave, till a fitter opportunity occurs for giving you further particulars of the "House of Under;" in the meanwhile, believe me, courteous reader, yours, sincerely,

UNDER THE ROSE.

THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

FRENCH REVOLUTION OF 1830

We quote a page or two from the second and concluding volume of Paris and its Historical Scenes, in the Library of Entertaining Knowledge, which gives the best account of la Grande Semaine that has yet appeared. The editor has taken Lord Bacon's advice—to read, not to take for granted—but to weigh and consider; and amidst the discrepancies of contemporary pamphleteers and journalists, his reader will not be surprised at the difficulty of obtaining correct information of what happens beneath our very window, as one of the great men of history confessed upwards of two centuries since. In this respect, mankind has scarcely progressed a jot, though men be more sceptical in not taking for granted.

Our extract is, we hope, to the point:

"It is curious to what an extent opposite feelings and opinions will colour even material scenes and objects to the eyes of different observers. Count Tasistro was also present at the capture of the Tuileries; and gives us in his narrative a description of what he witnessed of the conduct of the people after they had established themselves within the palace. Before presenting the reader, however, with what he says upon this subject, we will transcribe part of his account of his adventures in the earlier part of this day. 'The morning of the 29th,' he says, 'was ushered in by the dismal ringing of bells, the groans of distant guns, and the savage shouts of the populace; and I arose from a long train of dreams, which defied recollection as well as interpretation. The rabble, headed by a few beardless boys just let loose from the Polytechnic School and other seminaries, had been pleased to fix their head-quarters in our street. About half-past eleven, however, those of them who were collected here having heard that the popular forces who were fighting before the Louvre were nearly disabled by the cannon of the troops occupying that palace, their Polytechnic chief called upon them to follow him to the assistance of their brethren. Having entreated them to refrain from extravagant excesses, he rushed forward, and soon arrived at the scene of action. Here I saw him turn round and address his followers thus, 'Le cannon a déjà exterminé plusieurs de vos comarades; dans un instant il est à vous; suivez moi, et apprenez comme il faut mourir;' (the cannon has already destroyed numbers of your brethren; the next instant it will be directed against you: follow me, and learn how to die.) Having uttered these words, he darted forward, just as the gun which was pointed at him was discharged, and was blown into atoms. The people, however, following where he had led, in the enthusiasm of the moment seized the gun, and turned it immediately against the Swiss and the Guards that were stationed at the balconies of the Louvre. Other guns were afterwards taken—and the consequence was that the soldiers at last retreated with great precipitation, and concentrated their strength on the Place du Carrousel. The tricolour was already waving over the Louvre. I observed a little, insignificant urchin climb up the walls, and plant it during the contest.

"The last struggle made by the Guards for their royal master was to save the proud palace of his ancestors; but, alas, the attempt was vain. A storm of balls was poured in upon them from so many sides, that the little presence of mind they had preserved until now, deserted them at this trying moment; and after a few ineffectual discharges, they retreated toward the Champs Elysées; and the populace, unchecked by any power but their own will, rushed en masse into the regal mansion.

"During this attack, short as it was, I happened to be in a situation far more critical than that of the generality of the combatants on either side. On entering the Place du Carrousel by the archway leading from the Quays, we found the confusion extreme—and, as the fire besides grew every moment hotter and hotter, I felt the necessity of taking refuge somewhere, and in my agitation ran forward and sheltered myself under the Triumphal Arch. Here I passed the short interval during which the combat lasted in a confusion of all the senses, which extended minutes to months, and gave to something less than half a quarter of an hour the importance of a century; for I was all the time between the two fires. Fortunately, as I have said, the affair did not last very long; and when the victorious rabble at last rushed into the Tuileries, I followed the general movement, and soon after found myself in the throne hall, where I was joined by my two missing friends."

The Count now proceeds to inveigh in general terms against what he describes as the atrocious conduct of the unruly rabble—the devastation, pillage, and other enormities of which they were guilty. Having concluded this diatribe, he goes on with his narrative as follows: "Indeed the passion of mischief had taken such strong possession of the minds of all—the temptation was so widely thrown open wherever one went—that even I felt a touch of the desire; and, as I passed along the library hall, where a most splendid stock of books had been thrown on the floor, spying among many precious treasures a beautifully ornamented little volume, which, to say nothing of its gay appearance, promised to occupy no great room in the pocket, with the conviction that I was doing a good action, I picked it up. On opening it I found that it was neither a bible, nor a poem, nor a congurare (?), as I had anticipated, but simply a pocket memorandum-book in which his Majesty had been accustomed to note his parties de chasse, and the numbers of game he killed. I immediately thrust it into my pocket, and have since preserved it as a keepsake—but shall be most happy to restore it to the owner, should that august personage at any time feel disposed to claim it. Would that all the rest of the many articles that were this day pilfered were held as sacred, and ready to be as punctually surrendered!