Полная версия

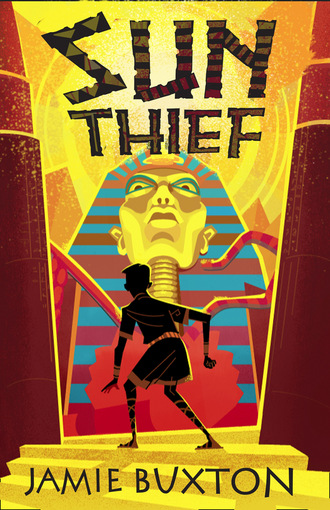

Sun Thief

With a last glance up to see if she’s angry, I squeeze into the space behind her. It’s darker round here. No sand. A flagstone rocks slightly under my feet. I manage to lever it up and peer into the dark hole. I should have brought a taper from the kitchen fire . . .

The darkness moves. I know I’m not imagining it. There’s just enough light to see something dark in there, as dark as water, gleaming like water, pouring itself like water, but with more purpose. And rustling with a dry sort of hiss.

Snake!

I jump back and the flagstone falls, but instead of a dull whump there’s a wet crunch, then . . . nothing. I wait, motionless. Still nothing.

Swallowing my fear, I reach down and touch the dead snake’s head, half severed by the edge of the falling flagstone, which I lift again and push back.

The first thing I find is a leather roll, wrapped tightly. The second is a small bag that is very, very heavy.

BOM-BOM-BOM-BOM-BOM. That’s my heart.

My hands are trembling as I pick up the objects, then I squeeze out from behind the goddess into the half-light at the front of the shrine. And there is the Quiet Gentleman.

‘So, boy,’ he says, ‘you found a way round my guard. Don’t drop what you’re carrying.’ His voice is calm and level.

I was about to, I admit, just to show that I don’t really care if I keep them or not. I can hardly breathe.

‘Talk, boy.’

‘Can’t.’

‘You just did.’

‘Found these. Cleaning. They yours?’ My voice is shaking and high. I hold out the leather roll and the heavy little bag. He takes the roll, which clinks like there’s metal in it.

‘You hang on to that,’ he says, nodding at the bag.

‘Why?’

‘Just while we have a little chat. Now’s the time to tell me everything you know.’

His voice is as flat as a knife. In that little shrine, with the sun slanting down through the holes in the roof, making everything striped, the truth comes pouring out of my mouth like grain from a slashed sack and it doesn’t stop until there’s no more truth to tell. The City of the Dead, the hiding, the rats, the men and all they said . . .

I finish and wait for the punishment I’m sure is coming, but the Quiet Gentleman just asks questions.

‘So you think I’m a tomb robber, do you, mud boy?’

‘I don’t want to think anything,’ I say.

‘Why’s that?’

‘If you’re a . . . you know what, you’ll kill me.’

‘So you know other tomb robbers?’

‘No!’ I almost shout.

‘Then don’t you worry about dying quite yet,’ the Quiet Gentleman says pleasantly. ‘I need you alive to answer a few more questions. These people you overheard: you never saw their faces?’

‘Sort of. I think one of them was here the night you turned up. He left as soon as you arrived, but I recognised his voice.’ I describe him, but can’t see any change in the Quiet Gentleman’s expression.

‘Will you know the voices if you hear them again?’

I nod. ‘And one was called Jatty.’

A pause. ‘Did the other have a voice like a smear of cold vomit?’

I nod enthusiastically, but suddenly he’s towering over me like a mountain. ‘And why did you look for my things? To steal? To sell them to these men if they found me? Are you lying? Did they catch you? Did you do a deal with them to save your life?’

‘NO! I just . . .’ I gabble. ‘I was scared to tell you in case you killed me. And then I was angry because you called me a cringer. I just – just wanted to look at what you had.’

He inhales like he’s about to say something, then breathes out through his nose. When he finally speaks, I know it’s not what he was going to say at first.

‘Well, in that case, you’d better look before you die,’ the Quiet Gentleman says. His eyes are like little dark slits, pushed up by his cheeks.

I open the bag. The object is wrapped in swathes of fabric.

‘Careful, boy.’

And I unwrap a statue. It’s the size of a kitten and the weight of a baby: a naked woman with the head of a cow and a sun balanced between her spreading horns.

‘There,’ the Quiet Gentleman says. ‘Know what you’re holding?’

‘A goddess,’ I whisper. ‘One of the dead goddesses. Hathor.’

The gold is warm and buttery under my fingers and somehow it feels like there’s give in it. I want to stroke it all over.

‘Melt her down and you could buy this whole town. Think you should do that?’

I nod. Shake.

‘It’s too beautiful,’ I say. ‘It’s worth more like this.’

‘You’re a strange one,’ the Quiet Gentleman says. ‘I should kill you, but you’re more use to me alive than dead so here’s how you pay me for your life. I want you to keep watching and listening. You see a group, any group, of three men in the street, you tell me.’

I nod.

‘Know what will happen if you sell me short?’

I nod.

‘Good, because now I won’t have to watch the street, boy. I’ll just have to watch you,’ he says.

Next day, Imi’s playing with her toys in the corner of the courtyard. She knows something’s wrong with me because her eyes keep flicking from me to the Quiet Gentleman and back again.

My father sticks his head out of the kitchen and calls me over.

‘How’s it going with our friend over there?’ he half talks, half mouths. He smells of onions and woodsmoke from cooking.

I shrug. ‘He’s fine.’

‘Would you say he’s taken a liking to you? Because your mother and I were wondering . . .’

‘What?’

‘Sometimes a gentleman likes the look of a boy and takes him on.’

‘Takes him on?’

‘As a companion. A servant. Remember, jobs are hard to come by in this day and age.’

‘But I’ve got a job,’ I protest. ‘I work here.’

‘There may be money in it,’ he says.

I have never been more hurt or angry in my life.

‘If you’re so keen to get rid of me, why not just ask him? Better still, why not make a FOR SALE sign and hang it round my neck?’

My father smiles weakly. ‘Come on, you know how things stand.’

‘He doesn’t want to take me on,’ I say bitterly. ‘He stares at me because he hates me.’

‘What have you done?’ he asks. Worried suddenly.

‘I behaved like you.’

It’s not a clever thing to say. My father’s face twists and he lifts his hand to hit me, then remembers the Quiet Gentleman and steps away.

‘We need more wine,’ he barks. ‘Go and get it.’

He says it loud enough for the Quiet Gentleman to hear, who meets my eye and moves his head ever so slightly to the courtyard gate, giving me permission to go.

I can’t quite read his face but there’s something showing on it. Something like pity. Something like disgust at his ending up in a place like this.

The wine merchant lives on the other side of town in a shop that smells of vinegar and mould. There are small jars of the good stuff on shelves and huge jars of the crap stuff out the back, which is what we sell to our customers.

The only way I can carry one of these giant jars is on my head and it feels like it’s trying to drive me straight down into the earth. The wine merchant loads me up and I stagger off like a two-legged camel, top-heavy and twice my normal height, down the dusty streets to the market square. I’m spotted by a gang of boys about my age who chuck pebbles at me, but just as I’m wobbling away from them, I hear another voice over their jeers and taunts.

‘Sure this is the street?’ it’s saying and I’m sure it’s the cold and sneery voice I heard in the City of the Dead.

‘Course. I’ve been here before. The inn’s just fifty paces the other side of the square. We’re almost there. This way. No, that way.’

If I was in any doubt before, I’m certain now. That was the stupid one.

‘That’s no guarantee our friend is still there.’

They’re right behind me. I can’t drop the wine jar and run, so I walk as fast as I can in a sort of smooth waddle. The gang starts to jeer again, but at least I’m getting away. Then the wine inside the jar starts slopping from side to side and I have to swerve all over the place to keep it balanced. People are pointing and laughing, but I’m round the last corner now and can see the entrance to the inn and I’m pretty certain that I’ve managed to pull away from the three men.

I walk through the entrance into the little courtyard, looking for the Quiet Gentleman. He’s there in his normal place, but for once he’s not looking at me. He’s listening to Imi who’s somehow roped him into one of her crazy games.

‘There you are!’ I say, trying to sound normal, but feeling like I have to scream. ‘Our friends have arrived!’

The Quiet Gentleman doesn’t look up.

‘HELLO, IT’S ME AND WE’VE GOT VISITORS!’

He looks up, head rolling on his neck like a boulder. He takes me in and then his eyes slip past me.

‘Three visitors,’ I say, but it’s too late for the warning to be any good. The three men rush past me. I shout: ‘IMI! WATCH OUT!’ and then it all kicks off.

The Quiet Gentleman pushes Imi out of the way; the huge pitcher of wine topples from my head, hits the ground and explodes. There’s a chaotic muddle of bodies and shouts, until suddenly it all stops and one of the three men is lying on the ground with blood pouring from his nose, the Quiet Gentleman is holding a knife to the second man’s throat – but the third has Imi by the hair and has his knife at her neck.

And then my parents come out of the kitchen to see what all the fuss is about. My mother opens her mouth to scream, but the man holding Imi snaps: ‘Quiet or I kill the brat.’

My father claps a hand over my mother’s mouth and holds her tight.

I’m paralysed with fear. I’m surrounded by shocked silence, apart from the moans of the man on the ground and the little bleats that come from my mother every time she breathes.

‘Hello, Nebet,’ the Quiet Gentleman says calmly. ‘I see you’ve messed up again.’ His eyes are just two dark slits and his lips are pulled back in a sort of snarl.

‘I wouldn’t say anything’s exactly messed up,’ Nebet says. I’m seeing the man with the cold and sneery voice for the first time. He’s young and would be good-looking, but his little dark eyes are too close together and there’s a twist to his mouth. ‘Boy,’ he says to me, ‘close the courtyard gates and if you call out I cut off the pretty girl’s nose. All right?’

I look at the Quiet Gentleman who gives a little nod.

When the gates are shut, the Quiet Gentleman gives a sorrowful shake of the head and says, ‘Nebet, are you absolutely sure this is what you want?’

‘Near enough, and just as soon as Bek manages to get off his knees we’ll pick up what we came for and be on our way,’ Nebet says.

‘And what about Brother Jatty?’ the Quiet Gentleman says. ‘Want to see the colour of his blood?’ Jatty must be the name of the man he’s holding, the one with the worried voice. The Quiet Gentleman’s knife is laid across the bump in his throat. Each time he swallows, the knife moves.

‘Not really, but I don’t care much,’ Nebet sneers. ‘Want to see the inside of this pretty little girl’s throat?’

A little bead of blood appears at the point of the knife. My mother screams, properly this time, and tries to writhe out of my father’s grip.

‘Hurt the girl and I hurt Jatty. Then it’ll be just you and me, Nebet,’ the Quiet Gentleman says, ‘and we all know how that will end: me staring down at you, and you staring down at your guts.’

‘Shall we see?’ Nebet says.

My mother’s wailing now, sounding more like an animal than a human. And then I’m running. It’s partly because I can’t stand it and partly because I just know something’s got to happen and I reckon no one can stop me.

I’m in the shrine and behind the statue and hauling up the flagstone before I’ve taken a breath, and then it’s back up into the sunshine and into the middle of the stand-off.

I rip open the bag and hold up Hathor so she gleams in the sunlight. No voice in my head, just a storm of madness.

‘PUT YOUR KNIVES DOWN!’ I scream so high my voice cracks. My breath is heaving like I’ve run round the town twice, but I feel as light as a feather. ‘Put your knives down or this is going over the wall. I mean it!’

I look from Nebet to the Quiet Gentleman and I can see doubt in their eyes.

‘Do that and you’ll regret it,’ the Quiet Gentleman says.

‘I don’t care,’ I say. ‘I’m warning both of you.’

A long pause. Horribly long. At last the Quiet Gentleman says, ‘Nebet, the boy’s shown us a way out. Shall we?’

They watch each other like dogs, then Nebet takes the knife from Imi’s neck and the Quiet Gentleman takes his from Jatty’s. They rest the blades in their open palms then lay them on the ground, all done slowly like a dance.

Jatty collapses. Imi runs across to her mother. I put the statue down and swallow.

‘So now we talk,’ the Quiet Gentleman says.

The knives might be on the ground, but the danger isn’t over. They leave Imi, but tie the rest of us up with strips torn from my father’s best tunic and bundle us into the kitchen. The fire is out and the evening’s bean stew is going cold.

Bek is the slow and stupid one the Quiet Gentleman knocked out. He’s standing in the doorway, staring at us. His nose is swelling and his eyes are blackening. He stinks like an old drunk because he rolled in the spilled wine.

My mother is still crying; my father has screwed his face up and is pleading for our lives in a continuous, whining moan. Imi is all snot and sniffs and I’m wishing they would all shut up so I can make out what the others are saying in the next-door room. I can hear the sound of voices rising and falling and it’s clear they’re arguing. I hear words that don’t seem to go together: horizon, workshop, and a name: Thutmose.

I’m thinking bitterly that if I’d just dropped the wine in the street and run here as fast as I could, I might have stopped all this happening. Now Imi is looking at me and I wish there was something I could do. I screw my face into a sort of smile. She disentangles my mother’s clutching fingers, wriggles over to me and curls up in my lap.

Then the voices next door stop and Jatty appears, pushing Bek out of the way.

‘All of you come next door,’ he says, his eyes darting around nervously. ‘Bek, untie them then keep watch at the courtyard gate. For the rest of you, things are going to change, but if you’re good you’ll have everything back as it was. One day.’

My mother starts to wail again. ‘What have we done? How have we offended you? Is it the boy? Take him away. He’s yours. He’s been no good from the day we found him. Snivelled as a baby and never done a decent day’s work in his life. Take him!’

‘Right,’ says Jatty, like a man trying to sound in control. ‘Time to get serious. We could kill you all, but then we’d have to get rid of your bodies and that’s always harder than people imagine. So we’re going to make a deal. You and you’ – he points at my parents with the tip of his knife – ‘will stay here. You’ll run the inn and look after Bek and Nebet who will also stay to make sure you behave.’

He nods at the Quiet Gentleman and continues. ‘Hannu and I are going on a trip and we’re going to take the girl as hostage. The boy comes too because he’s old enough to understand the situation and, according to Hannu, he’s good at looking after his sister and we might be busy.’

My mother screams. My father says: ‘Hush, hush. It’ll be all right. They won’t be going far. Tomorrow everything will be back to normal.’ He appeals to the Quiet Gentleman. ‘You’re not going far, are you, sir?’

‘We’re going upriver,’ Jatty says. ‘We’ll be away for as long as we need to be. It may be a month. It may be a year. But if word reaches us that you’ve talked, we’re going to take this little girl to the Great River and throw her to the crocodiles. Are you clear about that?’

My father’s skin is suddenly ashen. ‘A month? A year?’ is all he says.

‘As long as it takes,’ insists Jatty. ‘You behave, nothing will happen. Talk and she dies.’

My father opens his mouth then closes it. He looks like a fish gulping for air.

‘But why?’ I say. ‘You’ve got what you came for.’

Nebet glares at me. ‘Which is what?’

‘The statue.’

‘Oh, that,’ Jatty says. ‘You think that’s all we’re after? No, that’s more of a . . .’

‘Enough!’ the Quiet Gentleman snaps. ‘The less everyone knows, the better.’

‘Indeed,’ Nebet says. ‘And let no one forget it.’

And that’s that. My mother is crying and clasping Imi, who looks really scared. My father takes me to one side and says: ‘Look after her, boy, or I’ll follow you through the Two Kingdoms and into hell.’

For the first time in his life, he looks like he means it.

And I have no idea where we’re going. All I know is that it’s got something to do with the horizon, a workshop and a man called Thutmose.

We’re travelling up the Great River on a cargo boat.

The river is milky smooth and earthy brown. There are fields on either side and dusty date palms droop in the heat. The boat is long and wide, low in the water, weighed down with cargo. Small fishing boats hug the banks. I see a horse running across a field of grass so green it makes me want to laugh with joy because the horse is beautiful and the rider looks so free.

I’m standing right at the back of the boat, where the giant helmsman nestles the steering oar under one massive arm. I stand next to him, my own arm wrapped round the sternpost. When the helmsman moves the rudder, eddies bloom and the water chuckles. I feel happy.

If I walk from one end of the boat to the other, climbing over the bales of hay, sacks of grain, jars of oil and wine, stacks of wood, rolls of linen, that’s thirty big paces. If I walk from side to side, right in the middle where the mast is, that’s ten big paces. The sailors look at me, call me mad monkey and laugh, but not unkindly. Even though my world is ten paces wide and thirty paces long, I feel free.

Then Imi joins me. Her skin is dull as if the sun has dried it. My happiness turns to dust and falls away. She needs looking after and that’s my job, but I don’t know what to do. The helmsman glances down at her.

‘Water,’ he says in a deep voice. ‘The little girl needs a drink.’

I dip a ladle in the pitcher of water he keeps by him and hold it to Imi’s lips. At first she presses her lips together, but I remember how she used to do that when she was a baby. Always started off by saying no. I persist. She takes a sip, then another, then takes the ladle and tips it into her mouth and drinks deeply and the relief I feel is like a drink of cool water.

‘Where are we?’ she says.

‘On the river. The Great River.’

‘Where are we going?’

I look up at the helmsman, who pulls the corners of his mouth down and shrugs. ‘People it call it the Horizon, little girl, but if you want to call it by its full name, you can try the City of the Sun’s Horizon, Home of the Only Living God on Earth, Akenaten, Champion of the Sun Itself and his Wife, Nefertiti, the Beautiful One is Approaching. It is the new capital of the Land of the Two Kingdoms.’ He points to the river ahead of us. ‘See that boat? See how high she rides? She’s delivered her cargo and now she’s heading back downriver to pick up more.’

‘Is the boat a lady?’ Imi asks.

‘If you treat her right. If you don’t then she turns into a –’

‘Boy!’

The Quiet Gentleman’s picking his way down the boat towards us. He beckons to me.

‘Careful,’ he says, when we’re out of earshot. ‘You’ll have to keep her from talking and remember the story. I’m your uncle. We’re going to find work in Horizon City. The king has spies everywhere on the river, don’t forget.’

‘But Jatty’s talking to everyone,’ I protest. It’s true, though no one really wants to talk to him.

‘Jatty’s a fool and may have to be dealt with. Now, get your sister something to eat.’

‘But suppose she asks me when we’re going home? What do I say?’

‘The better she behaves, the sooner she’ll be going home. Tell her that.’

But it’s hard to keep an eye on Imi all the time. Every evening, when we drop anchor, the sailors gather round a small brazier and cook the fish they’ve caught. They save Imi the best bits, sing her songs and tie knots for her and, while I know I should keep her away in case she talks about the fight at the inn, I can’t when she seems to be happy with them.

Once I saw her ask the captain, who sits on a sort of throne just behind the mast, when she was going home. He looked embarrassed and shot a glance at the Quiet Gentleman. It took a while for me to work out that he was frightened and didn’t know what to say. It was then, I think, that I understood the Quiet Gentleman’s power, his ability to scare, applied to everyone and not just me. I found the thought strangely comforting.

It’s getting towards the evening of the second day and we’ve dropped anchor. Towns, villages and even fields have slid away behind us, though the land on either side is lush with reeds and grass. There’s a gentle bend in the river so we can’t see the boats behind us or ahead.

Imi’s asleep. I’m looking up at the stars in the clearest sky I have ever seen and wondering how the frogs can make quite so much noise when the Quiet Gentleman comes and sits beside me.

‘We’ve got a problem,’ is all he says.

‘Not of my making,’ I answer.

‘Not directly maybe,’ he says. ‘Jatty’s made a friend at last.’

I did notice that Jatty was hanging out with one particular sailor. ‘That skinny one with the face like a dog?’ I ask.

‘That’s the one. Notice anything odd about him?’

‘He wags his tail if you chuck him a bone?’

The Quiet Gentleman ignores my quite good joke. ‘He works less than the others, but the captain never shouts at him.’

‘So what?’

‘He’s a spy. Everything passes up and down the river: ships, goods, people, news. If the king wants to find out what’s going on in his kingdom, he just has to plant snitches on boats and in harbours.’

‘You think Jatty . . .’

‘Either Jatty can’t see a spy in front of his nose or he’s playing a dangerous game. Either way, his new friend has a supply of wine and Jatty’s trying to drink it all. That makes me worried too.’

‘And what do you want me to do about it?’ I snap. ‘I don’t want anything to do with Jatty. I’ve got my own worries.’

Just then something bumps against the side of the boat. The crewmen murmur and enough crowd to the side to tip the deck. Hannu’s hand folds itself around my arm.

‘That noise was a crocodile. Sailors feed them. Why do you think they do that?’

‘I don’t know,’ I say.

He narrows his eyes. ‘Let’s look at this another way. Why do you think crocodiles always wait where the reeds on the riverbank are trampled down?’

I shake my head.

‘It’s because they know that’s where the cattle drink. And why do you think crocodiles wait by the east bank of the river at sunset and the west bank at sunrise?’ Hannu asks.

I shake my head again.

‘So they can get close to the cattle behind the glare of the sun. Why am I telling you this?’

‘Because you like cows?’ I say.

‘A clever tongue will only get you so far in this world, boy. Work it out.’

‘Crocodiles are dangerous,’ I say. ‘The crew think that if they give them offerings, they won’t eat them.’