полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 282, November 10, 1827

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 10, No. 282, November 10, 1827

Architectural Illustrations

No. III.

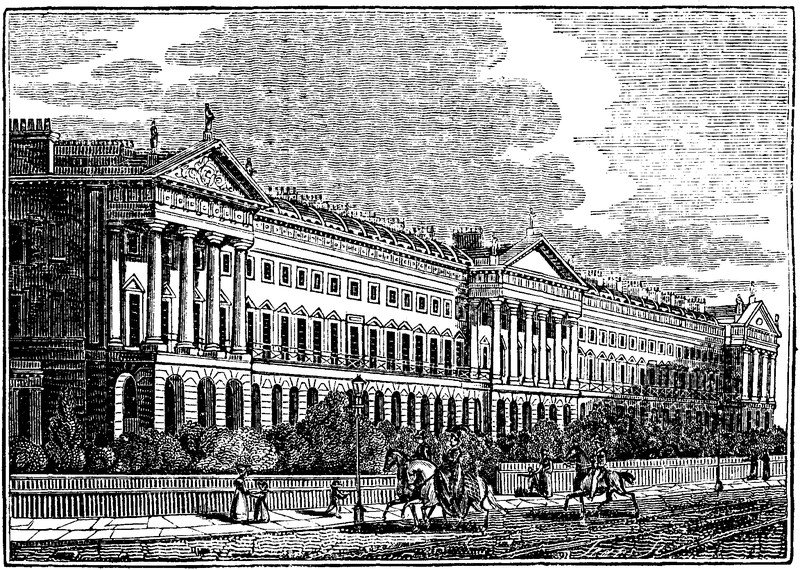

HANOVER TERRACE, REGENT'S PARK

"The architectural spirit which has arisen in London since the late peace, and ramified from thence to every city and town of the empire, will present an era in our domestic history." Such is the opinion of an intelligent writer in a recent number of Brande's "Quarterly Journal;" and he goes on to describe the new erections in the Regent's Park as the "dawning of a new and better taste, and in comparison with that which preceded it, a just subject of national exultation;" in illustration of which fact we have selected the subjoined view of Hanover Terrace, being the last group on the left of the York-gate entrance, and that next beyond Sussex-place, distinguishable by its cupola tops.

Hanover Terrace, unlike Cornwall and other terraces of the Regent's Park, is somewhat raised from the level of the road, and fronted by a shrubbery, through which is a carriage-drive. The general effect of the terrace is pleasing; and the pediments, supported on an arched rustic basement by fluted Doric columns, are full of richness and chaste design; the centre representing an emblematical group of the arts and sciences, the two ends being occupied with antique devices; and the three surmounted with figures of the Muses. The frieze is also light and simply elegant. The architect is Mr. Nash, to whose classic taste the Regent's Park is likewise indebted for other interesting architectural groups.

Altogether, Hanover Terrace may be considered as one of the most splendid works of the neighbourhood, and it is alike characteristic of British opulence, and of the progressive improvement of national taste. On the general merits of these erections we shall avail ourselves of the author already quoted, inasmuch as his remarks are uniformly distinguished by moderation and good taste.

"Regent's Park, and its circumjacent buildings, promise, in few years, to afford something like an equipoise to the boasted Palace-group of Paris. If the plan already acted upon is steadily pursued, it will present a union of rural and architectural beauty on a scale of greater magnificence than can be found in any other place. The variety is here in the detached groups, and not as formerly in the individual dwellings, by which all unity and grandeur of effect was, of course, annihilated. These groups, undoubtedly, will not always bear the eye of a severe critic, but altogether they exhibit, perhaps, as much beauty as can easily be introduced into a collection of dwelling-houses of moderate size. Great care has been, taken to give something of a classical air to every composition; and with this object, the deformity of door-cases has been in most cases excluded, and the entrances made from behind. The Doric and Ionic orders have been chiefly employed; but the Corinthian, and even the Tuscan, are occasionally introduced. One of these groups is finished with domes; but this is an attempt at magnificence which, on so small a scale, is not deserving of imitation."

THE ISLE OF SHEPPEY

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)SIR,—Under the Arcana of Science, in your last Number, I observed an account of the inroads made by the sea on the Isle of Sheppey, together with the exhumation there of numerous animal and vegetable remains. As an additional fact I inform you, that, at about three hundred feet below the surface of the sand-bank, (of which the island is composed,) there is a vast prostrate antediluvian forest, masses of which are being continually developed by the influence of marine agency, and exhibit highly singular appearances. When the workmen were employed some years back in sinking a well to supply the garrison with water, the aid of gunpowder was required to blast the fossil timber, it having attained, by elementary action and the repose of ages, the hard compactness of rock or granite stone. Aquatic productions also appear to observation in their natural shape and proportion, with the advantage of high preservation, to facilitate the study of the inquiring philosopher. I have seen entire lobsters, eels, crabs, &c. all transformed into perfect lapidifications. Many of these interesting bodies have been selected, and at the present time tend to enrich the elaborate collections of the Museum of London and the Institute of France. During the winter of 1825, in examining a piece of petrified wood, which I had picked up on the shore, we discovered a very minute aperture, barely the size of a pin-hole, and on breaking the substance by means of a large hammer, to our surprise and regret we crushed a small reptile that was concealed inside, and which, in consequence, we were unfortunately prevented from restoring to its original shape. The body was of a circular shape and iron coloured; but from the blood which slightly moistened the face of the instrument, we were satisfied it must have been animated. I showed the fragments of both to a gentleman in the island, who, like myself, lamented the accident, as it had, in all likelihood, deprived science of forming some valuable (perhaps) deductions on this incarcerated, or (if I may be allowed the expression) compound phenomenon. I have merely related the above incident in order to show the possibility of there being other creatures accessible to discovery under similar circumstances, and in their nature, perhaps homogeneous. I left the island next day, and therefore had no further opportunities of confirming such an opinion; but the place itself abounds with substances which would authorize such conjectures.

D. A. P.1

ANTICIPATED FRENCH MILLENNIUM, OR THE PARISIAN "TRIVIA."

(For the Mirror.)"Travellers of that rare tribe, Who've seen the countries they describe."

HANNAH MORE.When daudling diligences dragTheir lumbering length along2 no more—That odd anomaly!—or wagGon call'd, or coach—a misnomer3—That Cerberus three-bodied! andThat Cerberus of music!Such rattle with their nine-in-hand!O, Cerbere, an tu sic?When this, (and of Long Acre witsTo rival this would floor some!)When this at last the Frenchman quits.Then! then is the age d'or come!When coxcomb waiters know their trade,Nor mix their sauces4 with cookey's;When John's no longer chamber maid,And printed well a book is.When sorrel, garlic, dirty knife,Et cetera, spoil no dinners—(The punishment is after life,Are cooks to punish sinners?)When bucks are safe, nor streets displayA sea Mediterranean;5When Cloacina wends her wayIn streamlet sub-terranean.When houses, inside well as out,Are clean,6 and servants civil;7When dice (if e'er 'twill be I doubt)Send fewer—to the devil.When riot ends, and comfort reigns,Right English comfort8—playersAre fetter'd with no rhythmic9 chains—French priests repeat French prayers.10When Palais Royal vice subsides,11(Who plays there's a complete ass—)When footpaths grow on highway sides12—Then! then's the Aurea-Ætas!There, France, I leave thee.—Jean Taureau!13What think'st thou of thy neighbours?Or (what I own I'd rather know)What—think'st thou of MY LABOURS?A TRAVELLER OF 1827, (W. P.)

Carshalton.

CARRYING THE TAR BARRELS AT BROUGH, WESTMORELAND

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)SIR,—In the haste in which I wrote my last account of the carrying of "tar barrels" in Westmoreland,14 (owing to the pressure of time,) I omitted some most interesting information, and I think I cannot do better than supply the deficiency this year.

As I said before, the day is prepared for, about a month previously—the townsmen employ themselves in hagging furze for the "bon-fire," which is situated in an adjoining field. Another party go round to the different houses, grotesquely attired, supplicating contributions for the "tar barrels," and at each house, after receiving a donation, chant a few doggerel verses and huzza! It is, however, well that people should contribute towards defraying the expense, for if they do not get enough money they commit sad depredations, and if any one is seen carrying a barrel they wrest it from him.

For my part, I liked the "watch night" the best, and if it were possible to keep sober, one might enjoy the fun—sad havoc indeed was then made among the poultry—when ducks and fowls were crackling before the fire all night; in fact, a few previous days were regular shooting days, and the little birds were killed by scores. But ere morning broke in upon them, many of the merry group were lying in a beastly state under the chairs and tables, or others had gone to bed; but this is what they called spending a merry night. The day arrives, and a whole troop of temporary soldiers assemble in the town at 10 P.M. with their borrowed instruments and dresses, and a real Guy,—not a paper one,—but a living one—a regular painted old fellow, I assure you, with a pair of boots like the Ogre's seven leagued, seated on an ass, with the mob continually bawling out, "there's a par o'ye!"

Thus they parade the town—one of the head leaders knocks at the door—repeats the customary verses, while the other holds a silken purse for the cash, which they divide amongst them after the expenses are paid—and a pretty full purse they get too. In the evening so anxious are they to fire the stack, that lanterns may be seen glimmering in all parts of the field like so many will-o'-the-wisps; then follow the tar barrels, and after this boisterous amusement the scene closes, save the noise throughout the night, and for some nights after of the drunken people, who very often repent their folly by losing their situations.

Now, respecting the origin of this custom, I merely, by way of hint, submit, that in the time of Christian martyrdom, as tar barrels were used for the "burning at the stake" to increase the ravages of the flame:—the custom is derived,—out of rejoicings for the abolition of the horrid practice, and this they show by carrying them on their heads (as represented at page 296, vol. 8.), but you may treat this suggestion as you please, and perhaps have the kindness to substitute your own, or inquire into it.

W. H. H.

CUSTOM OF BAKING SOUR CAKES

(For the Mirror.)Rutherglen, in the county of Lanarkshire, has long been famous for the singular custom of baking what are called sour cakes. About eight or ten days before St. Luke's fair (for they are baked at no other time in the year), a certain quantity of oatmeal is made into dough with warm water, and laid up in a vessel to ferment. Being brought to a proper degree of fermentation and consistency, it is rolled up into balls proportionable to the intended largeness of the cakes. With the dough is commonly mixed a small quantity of sugar, and a little aniseed or cinnamon. The baking is executed by women only; and they seldom begin their work till after sunset, and a night or two before the fair. A large space of the house, chosen for the purpose, is marked out by a line drawn upon it. The area within is considered as consecrated ground, and is not, by any of the bystanders, to be touched with impunity. The transgression incurs a small fine, which is always laid out in drink for the use of the company. This hallowed spot, is occupied by six or eight women, all of whom, except the toaster, seat themselves on the ground, in a circular form, having their feet turned towards the fire. Each of them is provided with a bakeboard about two feet square, which they hold on their knees. The woman who toasts the cakes, which is done on an iron plate suspended over the fire, is called the queen, or bride, and the rest are called her maidens. These are distinguished from one another by names given them for the occasion. She who sits next the fire, towards the east, is called the todler; her companion on the left hand is called the trodler;15 and the rest have arbitrary names given them by the bride, as Mrs. Baker, best and worst maids, &c. The operation is begun by the todler, who takes a ball of the dough, forms it into a cake, and then casts it on the bakeboard of the trodler, who beats it out a little thinner. This being done, she, in her turn, throws it on the board of her neighbour; and thus it goes round, from east to west, in the direction of the course of the sun, until it comes to the toaster, by which time it is as thin and smooth as a sheet of paper. The first cake that is cast on the girdle is usually named as a gift to some man who is known to have suffered from the infidelity of his wife, from a superstitious notion, that thereby the rest will be preserved from mischance. Sometimes the cake is so thin, as to be carried by the current of the air up into the chimney. As the baking is wholly performed by the hand, a great deal of noise is the consequence. The beats, however, are not irregular, nor destitute of an agreeable harmony, especially when they are accompanied with vocal music, which is frequently the case. Great dexterity is necessary, not only to beat out the cakes with no other instrument than the hand, so that no part of them shall be thicker than another, but especially to cast them from one board to another without ruffling or breaking them. The toasting requires considerable skill; for which reason the most experienced person in the company is chosen for that part of the work. One cake is sent round in quick succession to another, so that none of the company is suffered to be idle. The whole is a scene of activity, mirth, and diversion. As there is no account, even by tradition itself, concerning the origin of this custom, it must be very ancient. The bread thus baked was, doubtless, never intended for common use. It is not easy to conceive how mankind, especially in a rude age, would strictly observe so many ceremonies, and be at so great pains in making a cake, which, when folded together, makes but a scanty mouthful.16 Besides, it is always given away in presents to strangers who frequent the fair. The custom seems to have been originally derived from paganism, and to contain not a few of the sacred rites peculiar to that impure religion; as the leavened dough, and the mixing it with sugar and spices, the consecrated ground, &c.; but the particular deity, for whose honour these cakes were at first made, is not, perhaps, easy to determine. Probably it was no other than the one known in Scripture (Jer. 7 ch. 18 v.) by the name of the Queen of Heaven, and to whom cakes were likewise kneaded by women.

J. S. W.

SONG

FROM METASTATIO(For the Mirror.)How in the depth of winter rudeA lovely flower is prized,Which in the month of April view'd,Perhaps has been despised.How fair amid the shades of nightAppears the stars' pale ray;Behold the sun's more dazzling light,It quickly fades away.E. L. I.

THE ORIGIN OF PETER'S PENCE

(For the Mirror.)The custom of paying "Peter's pence" is of Saxon origin; and they continued to be paid by the inhabitants of England, till the abolition of the Papal power. The event by which their payment was enacted is as follows:—Ethelbert, king of the east angles, having reigned single some time, thought fit to take a wife; for this purpose he came to the court of Offa, king of Mercia, to desire his daughter in marriage. Queenrid, consort of Offa, a cruel, ambitious, and blood-thirsty woman, who envied the retinue and splendour of the unsuspicious king, resolved in some manner to have him murdered, before he left their court, hoping by that to gain his immense riches; for this purpose she, with her malicious and fascinating arts, overcame the king—her husband, which she most cunningly effected, and, under deep disguises, laid open to him her portentous design; a villain was therefore hired, named Gimberd, who was to murder the innocent prince. The manner in which the heinous crime was effected was as cowardly as it was fatal: under the chair of state in which Ethelbert sat, a deep pit was dug; at the bottom of it was placed the murderer; the unfortunate king was then let through a trap-door into the pit; his fear overcame him so much, that he did not attempt resistance. Three months after this, Queenrid died, when circumstances convinced Offa of the innocence of Ethelbert; he therefore, to appease his guilt, built St. Alban's monastery, gave one-tenth part of his goods to the poor, and went in penance to Rome—where he gave to the Pope a penny for every house in his dominions, which were afterwards called Rome shot, or Peter's pence, and given by the inhabitants of England, &c. till 1533, when Henry VIII. shook off the authority of the Pope in this country.

T.C.

ARCANA OF SCIENCE

Black and White Swans

A few weeks since a black swan was killed by his white companions, in the neighbourhood of London. Of this extraordinary circumstance, an eye-witness gives the following account:—

I was walking, between four and five o'clock on Saturday afternoon, in the Regent's Park, when my attention was attracted by an unusual noise on the water, which I soon ascertained to arise from a furious attack made by two white swans on the solitary black one. The allied couple pursued with the greatest ferocity the unfortunate rara avis, and one of them succeeded in getting the neck of his enemy between his bill, and shaking it violently. The poor black with difficulty extricated himself from this murderous grasp, hurried on shore, tottered a few paces from the water's edge, and fell. His death appeared to be attended with great agony, stretching his neck in the air, fluttering his wings, and attempting to rise from the ground. At length, after about five minutes of suffering, he made a last effort to rise, and fell with outstretched neck and wings. One of the keepers came up at the moment, and found the poor bird dead. It is remarkable, that his foes never left the water in pursuit, but continued sailing up and down to the spot wherein their victim fell, with every feather on end, and apparently proud of their conquest.

Fascination of Snakes

I have often heard stories about the power that snakes have to charm birds and animals, which, to say the least, I always treated with the coldness of scepticism, nor could I believe them until convinced by ocular demonstration. A case occurred in Williamsburgh, Massachussets, one mile south of the house of public worship, by the way-side, in July last. As I was walking in the road at noon-day, my attention was drawn to the fence by the fluttering and hopping of a robin red-breast, and a cat-bird, which, upon my approach, flew up, and perched on a sapling two or three rods distant; at this instant a large black snake reared his head from the ground near the fence. I immediately stepped back a little, and sat down upon an eminence; the snake in a few moments slunk again to the earth, with a calm, placid appearance; and the birds soon after returned, and lighted upon the ground near the snake, first stretching their wings upon the ground, and spreading their tails, they commenced fluttering round the snake, drawing nearer at almost every step, until they stepped near or across the snake, which would often move a little, or throw himself into a different posture, apparently to seize his prey; which movements, I noticed, seemed to frighten the birds, and they would veer off a few feet, but return again as soon as the snake was motionless. All that was wanting for the snake to secure the victims seemed to be, that the birds should pass near his head, which they would probably have soon done, but at this moment a wagon drove up and stopped. This frightened the snake, and it crawled across the fence into the grass: notwithstanding, the birds flew over the fence into the grass also, and appeared to be bewitched, to flutter around their charmer, and it was not until an attempt was made to kill the snake that the birds would avail themselves of their wings, and fly into a forest one hundred rods distant. The movements of the birds while around the snake seemed to be voluntary, and without the least constraint; nor did they utter any distressing cries, or appear enraged, as I have often seen them when squirrels, hawks, and mischievous boys attempted to rob their nests, or catch their young ones; but they seemed to be drawn by some allurement or enticement, and not by any constraining or provoking power; indeed, I thoroughly searched all the fences and trees in the vicinity, to find some nest or young birds, but could find none. What this fascinating power is, whether it be the look or effluvium, or the singing by the vibration of the tail of the snake, or anything else, I will not attempt to determine—possibly this power may be owing to different causes in different kinds of snakes. But so far as the black snake is concerned, it seems to be nothing more than an enticement or allurement with which the snake is endowed to procure his fowl.—Professor Silliman's Journal.

Boring Marine Animals

The most destructive of these is the Teredo Navalis, a fine specimen of which was exhibited at a recent meeting of the Portsmouth Philosophical Society. This animal has been said to extend the whole length of the boring tube; but this assertion is erroneous, since the tubes are formed by a secretion from the body of the animal, and are often many feet in length, and circuitous in their course. This was shown to be the fact, by a large piece of wood pierced in all directions. The manner in which it affects its passage, and the interior of the tubes, were also described. The assertion that the Teredo does not attack teak timber was disproved; and its destructive ravages on the bottom of ships exemplified, by a relation of the providential escape of his majesty's ship Sceptre, which having lost some copper from off her bows, the timbers were pierced through to such an extent as to render her incapable of pursuing her voyage without repair.

Anthracite, or Stone Coal

Professor Silliman's last journal contains a very important article, illustrative of the practical application of this mineral; and the vast quantities of it that may be found in Great Britain renders the information highly valuable to our manufacturing interests. In no part of the world is anthracite, so valuable in the arts and for economical purposes, found so abundantly as in Pennsylvania. For the manufacture of iron this fuel is peculiarly advantageous, as it embraces little sulphur or other injurious ingredients; produces an intense steady heat; and, for most operations, it is equal, if not superior to coke. Bar iron, anchors, chains, steamboat machinery, and wrought-iron of every description, has more tenacity and malleability, with less waste of metal, when fabricated by anthracite, than by the aid of bituminous coal or charcoal, with a diminution of fifty per cent. in the expense of labour and fuel. For breweries, distilleries, and the raising of steam, anthracite coal is decidedly preferable to other fuel, the heat being more steady and manageable, and the boilers less corroded by sulphureous acid, while no bad effects are produced by smoke and bitumen. The anthracite of Pennsylvania is located between the Blue Bridge and Susquehannah; and has not hitherto been found in other parts of the state, except in the valley of Wyoming.

Holly Hedges

At Tynningham, the residence of the Earl of Harrington, are holly hedges extending 2,952 yards, in some cases 13 feet broad and 25 feet high. The age of these hedges is something more than a century. At the same place are individual trees of a size quite unknown in these southern districts. One tree measures 5 feet 3 in. in circumference at 3 feet from the ground; the stem is clear of branches to the height of 14 feet, and the total height of the tree is 54 feet. At Colinton House, the seat of Sir David Forbes; Hopetown House, and Gordon Castle are also several large groups of hollies, apparently planted by the hand of Nature.—Trans. Horticultural Society.

Egg Plants