полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 289, December 22, 1827

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 10, No. 289, December 22, 1827

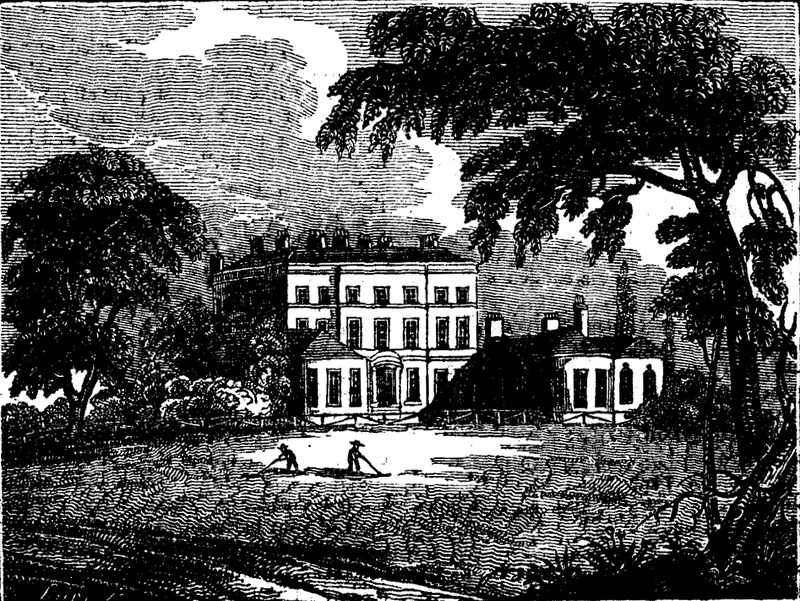

Bushy Park

Among the Suburban Beauties of The Metropolis, and As an Attraction For Home-tourists, Bushy is Entitled to Special Notice, Independent of Its Celebrity As the Retreat of Royalty—it Being The Residence Of his Royal Highness the Duke of Clarence, an Accurate Portrait Of Whom Will Be Presented, to Our Readers With the Usual supplementary Number At The Close of the Present Volume Of The Mirror.

Bushy Park is an appendage to the palace and honour of Hampton Court; and though far from assimilating to that splendid pile, it is better fitted for rural enjoyment, whilst its contiguity to the metropolis almost gives it the character of rus in urbe. 1 The residence is a handsome structure, and its arrangement is altogether well calculated for the indulgence of royal hospitality—a characteristic of its present distinguished occupant, as well as of that glorious profession, to the summit of which his royal highness has recently been exalted. The park, too, is well stocked with deer, and its rangership is confided to the duke. The pleasure grounds are tastefully disposed, and their beauty improved by the judicious introduction of temples and other artificial embellishments, among which, a naval temple, containing a piece of the mast of the Victory, before which Nelson fell, and a bust of the noble admiral, has been consecrated to his memory by the royal duke, with devotional affection, and the best feelings of a warm heart.

The park is a thoroughfare, and the circumstances by which this public claim was established are worthy of record, as a specimen of the justice with which the rights of the community are upheld in this country. The village Hampden, in the present case, was one Timothy Bennet, of whom there is a fine print, which the neighbours, who are fond of a walk in Bushy Park, must regard with veneration. It has under it this inscription:—"Timothy Bennet; of Hampton Wick, in Middlesex, shoemaker, aged 75, 1752. This true Briton, (unwilling to leave the world worse than he found it,) by a vigorous application of the laws of his country in the cause of liberty, obtained a free passage through Bushy Park, which had many years been withheld from the public." Regeneration (or the renewal of souls) is, however, a shoemaker's forte.

The above engraving of Bushy is copied from an elegant coloured view, drawn by Ziegler, and published by Griffiths, of Wellington-street, Strand.

THE FUGITIVE

A SCOTCH TALE

(For the Mirror.)It was now abute the gloaming when my ain same Janet (heav'n sain her saul) was sitting sae bieldy in a bit neuk ayant the ingle, while the winsome weans gathering around their minnie were listing till some auld spae wife's tale o' ghaists and worriecows; when on a sudden some ane tirled at the door pin.

"Here's your daddie, bairns," said the gudewife ganging till the door; but i' place o' their daddie, a tall chiel wrappit i' a big cloak, rushed like a fire flaught into the bield, and drappit doun on the sunkie ewest the ingle droghling and coghling.

"What's your wull, friend?" said Janet, glowering on him a' i' a gliff, "the gudeman's awa."

"Save me, save me," shrieghed the stranger, "the sleuth hounds are at my heels."

"But wha may ye be, maister," cried the dame, "I durstna dee your bidding while Jamie's frae the hause."

"Oh, dinna speir, dinna speir mistress," exclaimed the chiel a' in a curfuffle, "ainly for the loe of heav'n, hide me frae the red coats whilk are comin' belive—O God, they are here," he cried, as I entered the shealing, and uttering a piercing skirl, he sprung till the wa', and thrawing aff his cloak, drew his broad claymore, whilk glittered fearsome by the low o' the ingle.

"Hauld, hauld, 'tis the gudeman his nainsell," shreighed Janet, when the stranger drapping the point o' the sword, clingit till my hand, and while the scauding tear draps tricklit adoun his face prigged me to fend him.

"Tak' your certie o' that my braw callant," said I, "ne'er sail it be tauld o' Jamie Mc-Dougall, that he steeked his door again the puir and hauseless, an the bluidy sleuth hounds be on ye they'se find it ill aneugh I trow to get an inkling o' ye frae me, I'se sune shaw 'em the cauld shouther."

Sae saying, I gared him climb a rape by whilk he gat abune the riggin o' the bield, then steeking to the door thro' whilk he gaed, I jimp had trailed doun the rape, when in rinned twa red coat chiels, who couping ilka ane i' their gait begun to touzle out the ben, and the de'il gaed o'er Jock Wabster.

"Eh, sirs! eh, sirs!" cried I, "whatna gaits' that to steer a bodie, wad ye harry a puir chiel o' a' his warldly gear, shame till ye, shame till ye, shank yoursell's awa."

"Fusht, fusht, fallow," cried ane o' the churls, "nane o' your bourds wi' us, or ye may like to be the waur aff; where is the faus loon? we saw him gae doun the loaning afore the shealing, and here he maun needs be."

"Aweel, sirs," I exclaimed, "ye see there isna ony creatur here, our nainsell's out-taken; seek again an ye winna creed a bodie; may be the bogle is jumpit into the pot on the rundle-tree ower the ingle, or creepit into the meal ark or aiblins it scoupit thro' the hole as ye cam in at the door. Ye may threep and threep and wampish your arms abute, as muckle as ye wuss, ye silly gowks, I canna tell ye mair an I wad."

"May be the Highland tyke is right, cummer, (said one o' the red coats) and the fallow is jumpit thro' the bole, but harkye maister gudeman, an ye hae ony mair o' your barns-breaking wi us, ye'se get a sark fu' o' sair banes, that's a'."

"Hear till him, hear till him, Janet," said I, as the twa southron chiels gaed thro' the hole, trailing their bagganets alang wi' 'em; "winna the puir tykes hae an unco saft couch o' it, think ye, luckie, O 'tis a gude sight for sair e'en to see 'em foundering and powtering i' the latch o' the bit bog aneath."

"Nane o' your clashes e'enow, gudemon," said she, "but let the callant abune gang his gate while he may."

"Ye're aye cute, dame," I cried, thrawing the bit gy abune, and in a gliffing, doun jumpit the chiel, and a braw chiel he was sure enough, siccan my auld e'en sall ne'er see again, wi' his brent brow and buirdly bowk wrappit in a tartan plaid, wi' a Highland kilt.

"May the gude God o' heaven sain you," he said "and ferd you for aye, for the braw deed ye hae dreed the day; tak' this wee ring, gudemon, and tak' ye this ane, gudewife, and when ye look on this and on that, I rede ye render up are prayer to him abune for the weal o' Charles Edward, your unfortunate prince."

Sae speaking, he sped rath frae the bield, and was sune lost i' the glunch shadows o' the mirk night.

Mony and mony a day has since rollit ower me, and I am now but a dour carle, whose auld pow the roll o' time hath blanched; my bonnie Janet is gone to her last hame, lang syne, my bairns hae a' fa'en kemping for their king and country, and I ainly am left like a withered auld trunk, waiting heaven's gude time when I sall be laid i' the mouls wi' my forbears.

Abune—above.

Aiblins—perhaps.

Bagganet—bayonet.

Barns-breaking—idle frolic.

Belive—immediately.

Ben—inner apartment of a house that contains but two.

Bield—hut.

Bieldy—snug.

Bole—cottage window.

Bourds—jeers.

Brent-brow—smooth open forehead.

Buirdly-bowk—athletic frame.

Clashes—idle gossip.

Couping—overturning.

Cummer—comrade.

Curfuffle—agitation.

De'il gaed o'er Jock Wabster—everything went topsy-turvy.

Dour carle—rugged old man.

Dreed the day—done this day.

Droghling and coghling—puffing and blowing.

Ewest—nearest.

Fire flaught—flash of lightning.

Forbears—forefathers.

Fusht—tush.

Gared—made.

Gliff—fright.

Gliffing—very short time.

Gloaming—twilight.

Glowering—gazing.

Gy—rope.

Glunch—gloomy.

Harry—plunder.

Ingle—fire.

Ill—difficult.

Ilka—every.

Kemping—striving.

Laid i' the mouls—laid in the grave.

Low—flame.

Loaning—lane.

Luckie—dame.

Latch—mire.

Mirk—dark.

Out-taken—excepting.

Pow—head.

Powtering—groping.

Prigged—earnestly entreated.

Rath—quick.

Rede—pray.

Riggin—roof.

Sain—bless.

Sark fu' o' sair banes—sound beating.

Scoupit—scampered.

Shank yoursell's awa—take yourselves off.

Shealing—rude cottage.

Show 'em the cauld shouther—appear cold and reserved.

Skirl—shrill cry.

Sleuth-hounds—blood-hounds.

Speir—ask.

Steiked—shut.

Steer—injure.

Sunkie—low stool.

Threep—threaten.

Tirled at the door pin—knocked at the door.

Touzle out—ransack.

Tyke—dog.

Wampish—toss about.

Worriecows—hobgoblins.

Wuss—wish.

A GTHE INDIAN MAIDEN'S SONG,

BY WILLIAM SHOBERLThe youth I love is far away.O'er forest, river, brake, and glen;And distant, too, perchance the day,When I shall see him once again.Nine moons have wasted. 2 since we met,How sweetly, then, the moments flew!Methinks the fairy vision yetPortrays the joy that ZEMLA knew.In list'ning to the tale of strife,When Shone AZALCO'S prowess bright,The strange adventures of his life,That gave me such unmix'd delight.That dream of happiness is past!For ever fled those magic charms!The cruel moment came at last,That tore AZALCO from my arms!What bitter pangs my bosom rent,When he my sight no longer bless'd!To some lone spot my steps I bent,My secret sorrows there confess'd.My sighs, alas! were breath'd unheard,Could aught on earth dispel my grief?Nor smiling sun, nor minstrel bird,Can give this aching heart relief.Since he I love is far away,O'er forest, river, brake, and glen,And distant, too, perchance the day,When I shall see him once again.MERRY CHRISTMAS!

(For the Mirror.)"Do you look for ale and cakes here, you rude rascals?"SHAKSPEARE'S Henry the Eighth.Since, my dear readers, even in this season of busy festivity I can spare a few moments to write for your gratification, I venture to hope you will spare a few to read for mine.

And so here we are, once again on tiptoe for a merry Christmas and a happy new year. My good friends, especially my fair friends, permit me to wish you both. Yes, Christmas is here—Christmas, when winter and jollity, foul weather and fun, cold winds and hot pudding, good frosts and good fires, are at their meridian! Christmas! With what dear associations is it fraught! I remember the time when I thought that word cabalistical; when, in the gay moments of youth, it seemed to me a mysterious term for every thing that is delightful; and such is the force of early associations, that even now I cannot divest myself of them. Christmas has long ceased to be to me what it once was; yet do I even now hail its return with pleasure, with enthusiasm. But, alas! how differently is it viewed, not only by the same individual at different periods of life, but by different individuals of the same age; by the rich and poor, the wretched and the happy, the pampered and the penniless!

To proceed to the object of this paper, which is simply to throw together a few casual hints, connected with the period. I would beg my reader's attention, in the first place, to an odd superstition, countenanced by Shakspeare, and which, if he happens to lie awake some night, (say with the tooth-ache—what better?—for that purpose I mean,) he will have an opportunity of verifying. The passage which contains it is in Hamlet and exhibits at once his usual wildness of imagination, and a highly praiseworthy religious veneration for the season. Where the ghost vanishes upon the crowing of the cock, he takes occasion to mention its crowing all hours of the night about Christmas time. The last four lines comprise several other superstitions connected with the period:—

It faded on the crowing of the cock.Some say, that ever 'gainst that season comes,Wherein our Saviour's birth is celebrated,The bird of dawning singeth all night long.And then, they say, no spirit dares stir abroad:The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike;No fairy takes; no witch hath power to charm;So hallow'd and so gracious is the time.It is to be lamented that the hearty diet, properly belonging to the season, should have become almost peculiar to it; the Tatler recommends it throughout the year. "I shall begin," says Steele, "with a very earnest and serious exhortation to all my well-disposed readers, that they would return to the food of their forefathers, and reconcile themselves to beef and mutton. This was the diet which bred that hardy race of mortals who won the fields of Cressy and Agincourt. I need not go so high up as the history of Guy, earl of Warwick, who is well known to have eaten up a dun cow of his own killing. The renowned king Arthur is generally looked upon as the first who ever sat down to a whole roasted ox, which was certainly the best way to preserve the gravy; and it is farther added, that he and his knights sat about it at his round table, and usually consumed it to the very bones before they would enter upon any debate of moment. The Black Prince was a professed lover of the brisket; not to mention the history of the sirloin, or the institution of the order of Beefeaters, which are all so many evident and undeniable proofs of the great respect which our warlike predecessors have paid to this excellent food. The tables of the ancient entry of this nation were covered thrice a day with hot roast-beef; and I am credibly informed by an antiquary, who has searched the registers in which the bills of fare of the court are recorded, that instead of tea and bread and butter which have prevailed of late years, the maids of honour in queen Elizabeth's time were allowed three rumps of beef for their breakfast!"

Now this is manly, and so is the diet it advises; I recommend both to my readers. Let each determine to make one convert, himself that one. On Christmas day, let each dine off, or at least have on his table, the good old English fare, roast beef and plum-pudding! and does such beef as our island produces need recommendation? What more nutritive and delicious? and, for a genuine healthy Englishman, what more proper than this good old national English dish? Let him whose stomach will not bear it, look about and insure his life—I would not give much for it. It ought, above all other places, to be duly honoured in our officers' mess-rooms. As Prior says,

"If I take Dan Congreve right,Pudding and beef make Britons fight."So, then, if beef be indeed so excellent, we shall not much wonder that Shakspeare should say,

—"A pound of man's flesh Is not so estimable or profitable. As flesh of mutton, beeves, or goats!"The French have christened us (and I think it no disreputable sobriquet) Jack Roastbeef, from a notion we cannot live without roast-beef, any more than without plum-pudding, porter, and punch; however, the notion is palpably erroneous. We are proving more and more every day—to our shame be it spoken!—that we can live without it. At least do not let it be said we can pass a Christmas without it, merely to make way for turkeys, fricassees, and ragouts! "Oh, reform it altogether!"

England was always famous among foreigners for the celebration of Christmas, at which time our ancestors introduced many sports and pastimes unknown in other countries, or now even among ourselves. "At the feast of Christmas," says Stowe, "in the king's court, wherever he chanced to reside, there was appointed a lord of misrule, or master of merry disports; the same merry fellow made his appearance at the house of every nobleman and gentleman of distinction; and, among the rest, the lord mayor of London and the sheriffs had their lords of misrule, ever contending, without quarrel or offence, who should make the rarest pastime to delight the beholders." Alas! where are all these, or any similar, "merry disports" in our degenerate days? We have no "lords of misrule" now; or, if we have, they are of a much less innocent and pacific character. Mr. Cambridge, also, (No 104, of the World) draws a glowing picture of an ancient Christmas. "Our ancestors," says he, "considered Christmas in the double light of a holy commemoration and a cheerful festival; and accordingly distinguished it by devotion, by vacation from business, by merriment and hospitality. They seemed eagerly bent to make themselves and every body about them happy. With what punctual zeal did they wish one another a merry Christmas! and what an omission would it have been thought, to have concluded a letter without the compliments of the season! The great hall resounded with the tumultuous joys of servants and tenants, and the gambols they played served as an amusement to the lord of the mansion and his family, who, by encouraging every art that conduced to mirth and entertainment, endeavoured to soften the rigour of the season, and to mitigate the influence of winter. How greatly ought we to regret the neglect of mince-pies, which, besides the idea of merry-making inseparable from them, were always considered as the test of schismatics! How zealously were they swallowed by the orthodox, to the utter confusion of all fanatical recusants! If any country gentleman should be so unfortunate in this age as to lie under a suspicion of heresy, where will he find so easy a method of acquitting himself as by the ordeal of plum-porridge?" This alludes to the Puritans, who refused to observe Christmas, or any other festival of the church, either by devotion or merriment. And I regret to say there are certain modern "fanatical recusants," certain modern Puritans, as schismatical in this particular as their gloomy precursors. Mr. Cambridge then proceeds "to account for a revolution which has rendered this season (so eminently distinguished in former times) now so little different from the rest of the year," which he thinks "no difficult task." The reasons he assigns are, the decline of devotion, and the increase of luxury, the latter of which has extended rejoicings and feastings, formerly peculiar to Christmas, through the whole year; these have consequently lost their raciness, the appetite for amusement has become palled by satiety, and the relish for it, reserved formerly for this particular season, is now no longer peculiar to it, having been already dissipated and exhausted. Another cause he assigns is, "the too general desertion of the country, the great scene of hospitality." Now this was written just fifty-three years ago, and as all the causes assigned for the declension of this grand national festivity up to that period are incontrovertible, and have been operating even more powerfully ever since, they will sufficiently account for the still greater declension observable in our days. And the declension appears to me to consist in this,—there is more gastronomy and expanse, but less heartiness and hospitality; and these latter are the only legitimate characteristics of Englishmen. Be they then restored, this very Christmas, to the English character; the opportunity is fast approaching—be it employed.

I know nothing better to conclude with than a good old Christmas carol from Poor Robin's Almanack for 1695, preserved in Brand's Popular Antiquities, to which work I refer those of my readers who may require further information on the subject of Christmas customs and festivities:—

Now, thrice welcome, Christmas!Which brings us good cheer;Mince-pies and plum-pudding—Strong ale and strong beer;With pig, goose, and capon,The best that may be:So well doth the weatherAnd our stomachs agree.Observe how the chimneysDo smoke all about;The cooks are providingFor dinner no doubt.But those on whose tablesNo victuals appear,O may they keep LentAll the rest of the year!With holly and ivy,So green and so gay,We deck up our housesAs fresh as the day;With bays and rosemary,And laurel complete,—And every one nowIs a king in conceit,But as for curmudgeonsWho will not be free,I wish they may dieOn a two-legged tree!WILLIAM PALINTo the proof that we are not unseasonable, here are in this sheet—Merry Christmas! the Turks, (of a darker hue;) Exhibitions; a Consolatory "Population" Scrap; Hints for Singing after a good master; a Bunch of Facts on Turnips; a column on Liston—that living limner of laughter; and other seasonables.

MANNERS & CUSTOMS OF ALL NATIONS

No. XVII.

THE TURKS

(For the Mirror.)The Turks have a manly and prepossessing demeanour; being generally of a good stature, and remarkably well formed in their limbs. The men shave their heads, but wear long beards, and are extremely proud of their mustaches, which are usually turned downwards, and which give the other features of the face a cast of peculiar pensiveness. They wear turbans, sometimes white, of an enormous size on their heads, and never remove them but when they go to repose. Their breeches, or drawers, are united with their stockings, and they have slippers, which they never put off but when they enter a mosque, or the house of a great man. Large shirts are worn, and over them is a vest tied with a sash; the outer garment being a sort of loose gown. Every man, in whatever station he is, carries a dagger in his sash. The women's attire much resembles that of the other sex, only they have a cap on their heads, something like a bishop's mitre, instead of a turban. Their hair is beautiful and long, mostly black, but their faces, which are remarkably handsome, are so covered when they walk out, that nothing is to be seen but their eyes. The ladies of the sultan's haram are lovely virgins, either captives taken during war, or presents from the governors of provinces. They are never allowed to stir abroad except when the grand signior removes; and then they are put into close chariots, signals being made at certain distances that no man may approach the road through which the ladies pass, on pain of death. There are a great number of female slaves in the sultan's haram, whose task it is to wait on the ladies, who have, besides, a black eunuch for their superintendant.

There are three colleges in Turkey where the children of distinguished men are educated and fitted for state employments. The children are first approved by the grand signior before they are allowed to enter these seminaries; and none dare come into his majesty's presence who are not handsome and well-made. Silence is first taught them, and a becoming behaviour to their superiors; then they are instructed in the Mahometan faith, the Turkish and Persian languages, and afterwards in the Arabic. At the age of twenty-one they are taught all manner of manly exercises, and above all, the use of arms. As they advance to proficiency in these, and other useful arts, and as government places become vacant, they are preferred; but it is to be observed, that they generally attain the age of forty before they are thought capable of being entrusted with important slate affairs.

Those who hold any office under the grand signior are called his slaves; the term slave, in Turkey, signifying the most honourable title a subject can bear. The grand signior is commonly supposed among his own people, to be something more than human; for he is not bound by any laws except that of professing and maintaining the Mahometan religion. A stranger desiring to be admitted into his majesty's presence, is first examined by proper persons, and his arms taken from him; he is then ushered before the royal personage between two strong supporters, but is not even then permitted to approach near enough to kiss the sultan's foot. 3

This custom, which is observed by every sultan, originated in the following manner:—Amurath I. having obtained a great victory over the Christians, was on the field of battle with his officers viewing the dead, when a wounded Christian soldier, rising from among the slain, came staggering towards him. The king, supposing the man intended to beg for his life, ordered the guards to make way for him; but drawing near, he drew a dagger from under, his coat, and plunged it into the heart of the great king, who instantly died.