полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 350, January 3, 1829

RETROSPECTIVE GLEANINGS

THEATRICAL BILL

At a play acted in 1511, on the Feast of St. Margaret, the following disbursements were made as the charges of the exhibition:—

ROBINSON CRUSOE'S ISLAND

The United States ship, Vincennes, visited the island of Juan Fernandez, off the coast of Chili, a few months since, and remained there three days. There were two Yankees and six Otaheitans on the island. The former had formed a settlement for the purpose of supplying whale-ships with water, poultry, and vegetables. The soil is said to be astonishingly fertile.

—New York Shipping List, 1366.THE LETTER H

From an old History of England"Not superstitiously I speak, but H his letter stillHath been observed ominous to England's good or ill."Humber the Hun, with foreign arms, did first the brutes invade;Helen to Rome's imperial throne the British crown convey'd;Hengist and Horsus first did plant the Saxons in this isle;Hungar and Hubba first brought Danes, that sway'd here a long while;At Harold had the Saxon end at Hardy Knute the Dane;Henries the First and Second did restore the English reign;Fourth Henry first for Lancaster did England's crown obtain;Seventh Henry jarring Lancaster and York unites in peace;Henry the Eighth did happily Rome's irreligion cease.CHURCH OF AUSTIN FRIARS

The church of Austin Friars is one of the most ancient Gothic remains in the City of London. It belonged to a priory dedicated to St. Augustine, and was founded for the friars Eremites of the order of Hippo, in Africa, by Humphry Bohun, Earl of Hereford and Essex, 1253. A part of this once spacious building was granted by Edward VI. to a congregation of Germans and other strangers, who fled hither from religious persecutions. Several successive princes have confirmed it to the Dutch, by whom it has been used as a place of worship. J.M.C.

DAUPHIN OF FRANCE

The heir apparent of the crown of France derives his title of Dauphin from the following very singular circumstance. In 1349, Hubert, second Count of Dauphiny, being inconsolable for the loss of his heir and only child, who had leaped from his arms through a window of his palace at Grenoble into the river Isere, entered into a convent of jacobins, and ceded Dauphiny to Philip, a younger son of Philip of Valois (for 120,000 florins of gold each of the value of twenty sols or ten pence English,) on condition that the eldest son of the king of France should be always after styled "the Dauphin," from the name of the province thus ceded. Charles V., grandson to Philip of Valois, was the first who bore the title in 1530.

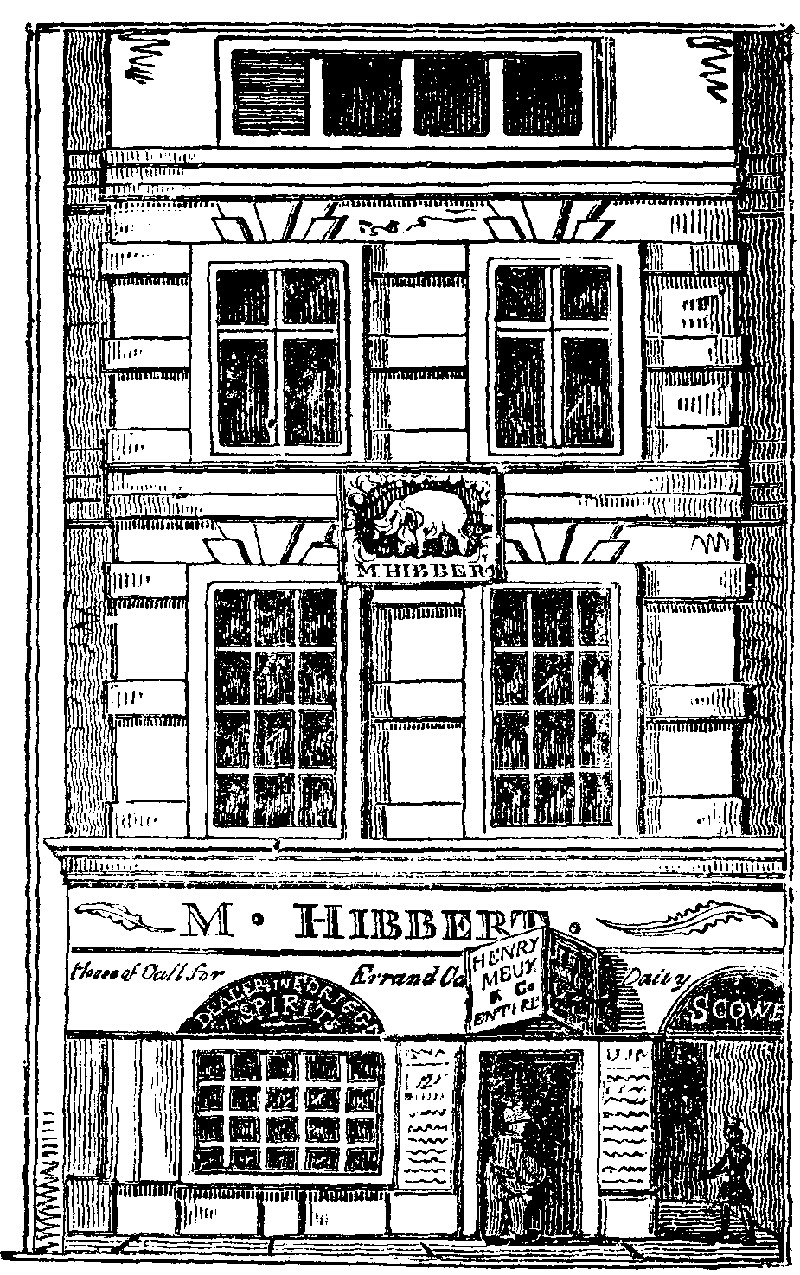

THE OLD ELEPHANT, FENCHURCH-STREET

Everything connected with the name of HOGARTH is interesting to the English reader. He was apprenticed to a silversmith, and from cutting cyphers on silver spoons, he rose to be sergeant painter to the king—and from engraving arms and shop-bills, to painting kings and queens—the very top of the artist's ladder. The soul-breathing impulses of genius enabled him to effect all this, and his example, (in support of the maxim, that "every man is the architect of his own fortune,") will be respected and cherished, at home and abroad, as long as self-advancement continues to be the great stimulus to aspiring industry.

The old Elephant public-house therefore merits the attention of all lovers of painting and genius; for in it, previous to his celebrity, lodged WILLIAM HOGARTH. It was built before the fire of London, and although so near, escaped its ravages; but the house was pulled down a short time since, and another of more commodious construction erected on its site. On the wall of the tap-room, in the old house, were four paintings by Hogarth: one representing the Hudson's Bay Company's Porters; another, his first idea for the Modern Midnight Conversation, (differing from the print in a circumstance too broad in its humour for the graver,) and another of Harlequin and Pierot seeming to be laughing at the figure in the last picture. On the first floor was a picture of Harlow Bush Fair, covered over with paint. This information is copied from an old print picked up in our "collecting" rambles, at the foot of which it is stated to have been obtained from "Mrs. Hibbert, who has kept the house between thirty and forty years, and received her information relating to Mr. Hogarth from persons at that time well acquainted with him." The paintings were, we believe, removed previous to the destruction of the old house.

To the searchers into life and manners, Hogarth's moral paintings, to which branch of art the above belong, are treasures of great prize; and whether over his originals at the gallery in Pall Mall, or their copies at the printsellers—the Elephant in Fenchurch-street, or the "painting moralist's" tomb in Chiswick churchyard—Englishmen have just cause to be proud of his name.

THE SELECTOR

AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS DAYS DEPARTED; OR, BANWELL HILL:

A Lay of the Severn Sea, by the Rev. W. Lisle BowlesThis is a delightful volume—full of nature and truth—and in every respect worthy of "one of the most elegant, pathetic, and original living poets of England." Moreover, it is just such a book as we expected from the worthy vicar of Bremhill; dedicated to the Bishop of Bath and Wells; and dated from Bremhill Parsonage, of which interesting abode we inserted an unique description in our last volume.

As our principal object is to give a few of the poetical pictures, we shall be very brief with the prose, and merely quote an outline of the poem. Mr. Bowles, it appears, is a native of the district in which he resides, and this circumstance introduces some beautiful retrospective feelings:—

But awhile,Here let me stand, and gaze upon the scene,Array'd in living light around, and markThe morning sunshine,—on that very shoreWhere once a child I wander'd,—Oh! return(I sigh,) "return a moment, days of youth,Of childhood,—oh, return!" How vain the thought,Vain as unmanly! yet the pensive Muse,Unblam'd, may dally with imaginings;For this wide view is like the scene of life,Once travers'd o'er with carelessness and glee,And we look back upon the vale of years,And hear remembered voices, and behold,In blended colours, images and shadesLong pass'd, now rising, as at Memory's call,Again in softer light.The poem then proceeds with a description of an antediluvian cave at Banwell, and a brief sketch of events since the deposit; but, as Mr. Bowles observes, poetry and geological inquiry do not very amicably travel together; we must, therefore, soon get out of the cave:—

But issuing from the Cave—look round—beholdHow proudly the majestic Severn ridesOn the sea,—how gloriously in lightIt rides! Along this solitary ridge,Where smiles, but rare, the blue Campanula,Among the thistles, and grey stones, that peepThrough the thin herbage—to the highest pointOf elevation, o'er the vale below,Slow let us climb. First, look upon that flow'rThe lowly heath-bell, smiling at our feet.How beautiful it smiles alone! The Pow'r,that bade the great sea roar—that spread the Heav'ns—That call'd the sun from darkness—deck'd that flow'r,And bade it grace this bleak and barren hill.Imagination, in her playful mood,Might liken it to a poor village maid,Lowly, but smiling in her lowliness,And dress'd so neatly, as if ev'ry dayWere Sunday. And some melancholy BardMight, idly musing, thus discourse to it:—"Daughter of Summer, who dost linger here.Decking the thistly turf, and arid hill,Unseen—let the majestic DahliaGlitter, an Empress, in her blazonryOf beauty; let the stately Lily shine,As snow-white as the breast of the proud Swan,Sailing upon the blue lake silently,That lifts her tall neck higher, as she viewsThe shadow in the stream! Such ladies brightMay reign unrivall'd, in their proud parterres!Thou would'st not live with them; but if a voice,Fancy, in shaping mood, might give to thee,To the forsaken Primrose, thou would'st say,'Come, live with me, and we two will rejoice:—Nor want I company; for when the seaShines in the silent moonlight, elves and fays,Gentle and delicate as Ariel,That do their spiritings on these wild bolts—Circle me in their dance, and sing such songsAs human ear ne'er heard!'"—But cease the strain,Lest Wisdom, and severer Truth, should chide.Next is a sketch of Steep Holms, introducing the following exquisite episode:

Dreary; but on its steepThere is one native flower—the Piony.She sits companionless, but yet not sad:She has no sister of the summer-field,That may rejoice with her when spring returns.None, that in sympathy, may bend its head,When the bleak winds blow hollow o'er the rock,In autumn's gloom!—So Virtue, a fair flow'r,Blooms on the rock of care, and though unseen,It smiles in cold seclusion, and remoteFrom the world's flaunting fellowship, it wearsLike hermit Piety, that smile of peace,In sickness, or in health, in joy or tears,In summer-days, or cold adversity;And still it feels Heav'n's breath, reviving, stealOn its lone breast—feels the warm blessednessOf Heaven's own light about it, though its leavesAre wet with ev'ning tears!So smiles this flow'r:And if, perchance, my lay has dwelt too long.Upon one flower which blooms in privacy,I may a pardon find from human hearts,For such was my poor Mother!4We pass over some marine sketches, which are worthy of the Vernet of poets, a touching description of the sinking of a packet-boat, and the first sound and sight of the sea—the author's childhood at Uphill Parsonage—his reminiscences of the clock of Wells Cathedral—and some real villatic sketches—a portrait of a Workhouse Girl—some caustic remarks on prosing and prig parsons, commentators, and puritanical excrescences of sects—to some unaffected lines on the village school children of Castle-Combe, and their annual festival. This is so charming a picture of rural joy, that we must copy it:—

If we would see the fruits of charity.Look at that village group, and paint the scene.Surrounded by a clear and silent stream,Where the swift trout shoots from the sudden ray,A rural mansion, on the level lawn,Uplifts its ancient gables, whose slant shadeIs drawn, as with a line, from roof to porch,Whilst all the rest is sunshine. O'er the treesIn front, the village-church, with pinnacles,And light grey tow'r, appears, while to the rightAn amphitheatre of oaks extendsIts sweep, till, more abrupt, a wooded knoll,Where once a castle frown'd, closes the scene.And see, an infant troop, with flags and drum,Are marching o'er that bridge, beneath the woods,On—to the table spread upon the lawn,Raising their little hands when grace is said;Whilst she, who taught them to lift up their heartsIn prayer, and to "remember, in their youth,"God, "their Creator,"—mistress of the scene,(Whom I remember once, as young,) looks on,Blessing them in the silence of her heart.And, children, now rejoice,—Now—for the holidays of life are few;Nor let the rustic minstrel tune, in vain,The crack'd church-viol, resonant to-day,Of mirth, though humble! Let the fiddle scrapeIts merriment, and let the joyous groupDance, in a round, for soon the ills of lifeWill come! Enough, if one day in the year,If one brief day, of this brief life, be givenTo mirth as innocent as yours!Then we have an "aged widow" reading "GOD'S own Word" at her cottage-door, with her daughter kneeling beside her—a sketch from those halcyon days, when, in the beautiful allegory of Scripture, "every man sat under his own fig-tree." This is followed by the "Elysian Tempe of Stourhead," the seat of Sir Richard Colt Hoare, to whose talents and benevolence Mr. Bowles pays a merited tribute. Longleat, the residence of the Bishop of Bath and Wells, succeeds; and Marston, the abode of the Rev. Mr. Skurray, a friend of the author from his "youthful days," introduces the following beautiful descriptive snatch:—

And witness thou,Marston, the seat of my kind, honour'd friend—My kind and honour'd friend, from youthful days.Then wand'ring on the banks of Rhine, we sawCities and spires, beneath the mountains blue,Gleaming; or vineyards creep from rock to rock;Or unknown castles hang, as if in clouds;Or heard the roaring of the cataract.Far off,5 beneath the dark defile or gloomOf ancient forests—till behold, in light,Foaming and flashing, with enormous sweep,Through the rent rocks—where, o'er the mist of spray,The rainbow, like a fairy in her bow'r,Is sleeping while it roars—that volume vast,White, and with thunder's deaf'ning roar, comes down.Part III. opens with the following metaphorical gem:—

The show'r is past—the heath-bell, at our feet,Looks up, as with a smile, though the cold dewHangs yet within its cup, like Pity's tearUpon the eye-lids of a village-child!This is succeeded by a poetic panorama of views from the Severn to Bristol, introducing a solitary ship at sea—and the "solitary sand:"—

No sound was heard,Save of the sea-gull warping on the wind,Or of the surge that broke along the shore,Sad as the seas.A picture of Bristol is succeeded by some scenes of great picturesque beauty—as Wrington, the birth-place of the immortal Locke; Blagdon, the rural rectory of

Langhorne, a pastor and a poet too;and Barley-Wood, the seat of Mrs. Hannah More. Mr. Bowles also tells us that the music of "Auld Robin Gray" was composed by Mr. Leaver, rector of Wrington; and then adds a complimentary ballad to Miss Stephens on the above air—

Sung by a maiden of the South, whose look—(Although her song be sweet)—whose look, whose life,Is sweeter than her song.The last Part (IV.) contains some exquisite Sonnets, and the poem concludes with a "Vision of the Deluge," and the ascent of the Dove of the ark—in which are many sublime touches of the mastery of poetry. There are nearly forty pages of Notes, for whose "lightness" and garrulity Mr. Bowles apologizes.

Altogether, we have been much gratified with the present work. It contains poetry after our own heart—the poetry of nature and of truth—abounding with tasteful and fervid imagery, but never drawing too freely on the stores of fancy for embellishment. We could detach many passages that have charmed and fascinated us in out reading; but one must suffice for an epigrammatic exit:—

—Hope's still light beyond the storms of Time.SCENERY OF THE OHIO

The heart must indeed be cold that would not glow among scenes like these. Rightly did the French call this stream La Belle Rivière, (the beautiful river.) The sprightly Canadian, plying his oar in cadence with the wild notes of the boat-song, could not fail to find his heart enlivened by the beautiful symmetry of the Ohio. Its current is always graceful, and its shores every where romantic. Every thing here is on a large scale. The eye of the traveller is continually regaled with magnificent scenes. Here are no pigmy mounds dignified with the name of mountains, no rivulets swelled into rivers. Nature has worked with a rapid but masterly hand; every touch is bold, and the whole is grand as well as beautiful; while room is left for art to embellish and fertilize that which nature has created with a thousand capabilities. There is much sameness in the character of the scenery; but that sameness is in itself delightful, as it consists in the recurrence of noble traits, which are too pleasing ever to be viewed with indifference; like the regular features which we sometimes find in the face of a lovely woman, their charm consists in their own intrinsic gracefulness, rather than in the variety of their expressions. The Ohio has not the sprightly, fanciful wildness of the Niagara, the St. Lawrence, or the Susquehanna, whose impetuous torrents, rushing over beds of rocks, or dashing against the jutting cliffs, arrest the ear by their murmurs, and delight the eye with their eccentric wanderings. Neither is it like the Hudson, margined at one spot by the meadow and the village, and overhung at another by threatening precipices and stupendous mountains. It has a wild, solemn, silent sweetness, peculiar to itself. The noble stream, clear, smooth, and unruffled, swept onward with regular majestic force. Continually changing its course, as it rolls from vale to vale, it always winds with dignity, and avoiding those acute angles, which are observable in less powerful streams, sweeps round in graceful bends, as if disdaining the opposition to which nature forces it to submit. On each side rise the romantic hills, piled on each other to a tremendous height; and between them are deep, abrupt, silent glens, which at a distance seem inaccessible to the human foot; while the whole is covered with timber of a gigantic size, and a luxuriant foliage of the deepest hues. Throughout this scene there is a pleasing solitariness, that speaks peace to the mind, and invites the fancy to soar abroad, among the tranquil haunts of meditation. Sometimes the splashing of the oar is heard, and the boatman's song awakens the surrounding echoes; but the most usual music is that of the native songsters, whose melody steals pleasingly on the ear, with every modulation, at all hours, and in every change of situation.—Hon. Judge Hall's Letters from the West.

SNOW-WOMAN'S STORY

By Miss Edgeworth"Yes, madam, I bees an Englishwoman, though so low now and untidy like—it's a shame to think of it—a Manchester woman, ma'am—and my people was once in a bettermost sort of way—but sore pinched latterly." She sighed, and paused.

"I married an Irishman, madam," continued she, and sighed again.

"I hope he gave you no reason to sigh," said Gerald's father.

"Ah, no, sir, never!" answered the Englishwoman, with a faint sweet smile. "Brian Dermody is a good man, and was always a koind husband to me, as far and as long as ever he could, I will say that—but my friends misliked him—no help for it. He is a soldier, sir,—of the forty-fifth. So I followed my husband's fortins, as nat'ral, through the world, till he was ordered to Ireland. Then he brought the children over, and settled us down there at Bogafin in a little shop with his mother—a widow. She was very koind too. But no need to tire you with telling all. She married again, ma'am, a man young enough to be her son—a nice man he was to look at too—a gentleman's servant he had been. Then they set up in a public-house. Then the whiskey, ma'am, that they bees all so fond of—he took to drinking it in the morning even, ma'am—and that was bad, to my thinking."

"Ay, indeed!" said Molly, with a groan of sympathy; "oh the whiskey! if men could keep from it!"

"And if women could!" said Mr. Crofton in a low voice.

The Englishwoman looked up at him, and then looked down, refraining from assent to his smile.

"My mother-in-law," continued she, "was very koind to me all along, as far as she could. But one thing she could not do; that was, to pay me back the money of husband's and mine that I lent her. I thought this odd of her—and hard. But then I did not know the ways of the country in regard to never paying debts."

"Sure it's not the ways of all Ireland, my dear," said Molly; "and it's only them that has not that can't pay—how can they?"

"I don't know—it's not for me to say," said the Englishwoman, reservedly; "I am a stranger. But I thought if they could not pay me, they need not have kept a jaunting-car."

"Is it a jaunting-car?" cried Molly. She pushed from her the chair on which she was leaning—"Jaunting-car bodies! and not to pay you!—I give them up intirely. Ill-used you were, my poor Mrs. Dermody—and a shame! and you a stranger! But them were Connaught people. I ask your pardon—finish your story."

"It is finished, ma'am. They were ruined, and all sold; and I could not stay with my children to be a burthen. I wrote to husband, and he wrote me word to make my way to Dublin, if I could, to a cousin of his in Pill-lane—here's the direction—and that if he can get leave from his colonel, who is a good gentleman, he will be over to settle me somewhere, to get my bread honest in a little shop, or some way. I am used to work and hard-*ship; so I don't mind. Brian was very koind in his letter, and sent me all he had—a pound, ma'am—and I set out on my journey on foot, with the three children. The people on the road were very koind and hospitable indeed; I have nothing to say against the Irish for that; they are more hospitabler a deal than in England, though not always so honest. Stranger as I was, I got on very well till I came to the little village here hard by, where my poor boy that is gone first fell sick of the measles. His sickness, and the 'pot'ecary' stuff and all, and the lodging and living ran me very low. But I paid all, every farthing; and let none know how poor I was, for I was ashamed, you know, ma'am, or I am sure they would have helped me, for they are a koind people, I will say that for them, and ought so to do, I am sure. Well, I pawned some of my things, my cloak even, and my silk bonnet, to pay honest; and as I could not do no otherwise, I left them in pawn, and, with the little money I raised, I set out forwards on my road to Dublin again, so soon as I thought my boy was able to travel. I reckoned too much upon his strength. We had got but a few miles from the village when he dropped, and could not get on; and I was unwilling and ashamed to turn back, having so little to pay for lodgings. I saw a kind of hut, or shed, by the side of a hill. There was nobody in it. It was empty of every thing but some straw, and a few turf, the remains of a fire. I thought there would be no harm in taking shelter in it for my children and myself for the night. The people never came back to whom it belonged, and the next day my poor boy was worse; he had a fever this time. Then the snow came on. We had some little store of provisions that had been made up for us for the journey to Dublin, else we must have perished when we were snowed up. I am sure the people in the village never know'd that we were in that hut, or they would have come to help us, for they bees very koind people. There must have been a day and a night that passed, I think, of which I know nothing. It was all a dream. When I got up from my illness, I found my boy dead—and the others with famished looks. Then I had to see them faint with hunger."

The poor woman had told her story without any attempt to make it pathetic, and thus far without apparent emotion or change of voice; but when she came to this part, and spoke of her children, her voice changed and failed—she could only add, looking at Gerald, "You know the rest, master; Heaven bless you!"

The Christmas BoxTHE COSMOPOLITE

ENGLISH GARDENS

We are veritable sticklers for old customs; and accordingly at this season of the year, have our room decorated with holly and other characteristic evergreens. For the last hour we have been seated before a fine bundle of these festive trophies; and, strange as it may seem, this circumstance gave rise to the following paper. The holly reminded us of the Czar Peter spoiling the garden-hedge at Sayes Court; this led us to John Evelyn, the father of English gardening: and the laurels drove us into shrubbery nooks, and all the retrospections of our early days, and above all to our early love of gardens. Our enthusiasm was then unaffected and uninfluenced by great examples; we had neither heard nor read of Lord Bacon nor Sir William Temple, nor any other illustrious writer on gardening; but this love was the pure offspring of our own mind and heart. Planting and transplanting were our delight; the seed which our tiny hands let fall into the bosom of the earth, we almost watched peeping through little clods, after the kind and quickening showers of spring; and we regarded the germinating of an upturned bean with all the surprise and curiosity of our nature. As we grew in mind and stature, we learned the loftier lessons of philosophy, and threw aside the "Pocket Gardener," for the sublime chapters of Bacon and Temple; and as the stream of life carried us into its vortex, we learned to contemplate their pages as the living parterres of a garden, and their bright imageries as fascinating flowers. As we journeyed onward through the busy herds of crowded cities, we learned the holier influences of gardens in reflecting that a garden has been the scene of man's birth—his fall—and proffered redemption.