Полная версия

Ultralearning

courtesy of the author

UNCOVERING THE ULTRALEARNERS

On the surface, projects such as Benny Lewis’s linguistic adventures, Roger Craig’s trivia mastery, and Eric Barone’s game development odyssey are quite different. However, they represent instances of a more general phenomenon I call ultralearning.* As I dug deeper, I found more stories. Although they differed in the specifics of what had been learned and why, they shared a common thread of pursuing extreme, self-directed learning projects and employed similar tactics to complete them successfully.

Steve Pavlina is an ultralearner. By optimizing his university schedule, he took a triple course load and completed a computer science degree in three semesters. Pavlina’s challenge long predated my own experiment with MIT courses and was one of the first inspirations that showed me compressing learning time might be possible. Done without the benefit of free online classes, however, Pavlina attended California State University, Northridge, and graduated with actual degrees in computer science and mathematics.

Diana Jaunzeikare embarked on an ultralearning project to replicate a PhD in computational linguistics. Benchmarking Carnegie Mellon University’s doctoral program, she wanted to not only take classes but also conduct original research. Her project had started because going back to academia to get a real doctorate would have meant leaving the job she loved at Google. Like many other ultralearners before her, Jaunzeikare’s project was an attempt to fill a gap in education when formal alternatives didn’t fit with her lifestyle.

Facilitated by online communities, many ultralearners operate anonymously, their efforts observable only by unverifiable forum postings. One such poster at Chinese-forums.com, who goes only by the username Tamu, extensively documented his process of studying Chinese from scratch. Devoting “70–80+ hours each week” over four months, he challenged himself to pass the HSK 5, China’s second highest Mandarin proficiency exam.

Other ultralearners shed the conventional structures of exams and degrees altogether. Trent Fowler, starting in early 2016, embarked on a yearlong effort to become proficient in engineering and mathematics. He titled it the STEMpunk Project, a play on the STEM fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics he wanted to cover and the retrofuturistic steampunk aesthetic. Fowler split his project into modules. Each module covered a particular topic, including computation, robotics, artificial intelligence, and engineering, but was driven by hands-on projects instead of copying formal classes.

Every ultralearner I encountered was unique. Some, like Tamu, preferred punishing, full-time schedules to meet harsh, self-imposed deadlines. Others, like Jaunzeikare, managed their projects on the side while maintaining full-time jobs and work obligations. Some aimed at the recognizable benchmarks of standardized exams, formal curricula, and winning competitions. Others designed projects that defied comparison. Some specialized, focusing exclusively on languages or programming. Others desired to be true polymaths, picking up a highly varied set of skills.

Despite their idiosyncrasies, the ultralearners had a lot of shared traits. They usually worked alone, often toiling for months and years without much more than a blog entry to announce their efforts. Their interests tended toward obsession. They were aggressive about optimizing their strategies, fiercely debating the merits of esoteric concepts such as interleaving practice, leech thresholds, or keyword mnemonics. Above all, they cared about learning. Their motivation to learn pushed them to tackle intense projects, even if it often came at the sacrifice of credentials or conformity.

The ultralearners I met were often unaware of one another. In writing this book, I wanted to bring together the common principles I observed in their unique projects and in my own. I wanted to strip away all the superficial differences and strange idiosyncrasies and see what learning advice remains. I also wanted to generalize from their extreme examples something an ordinary student or professional can find useful. Even if you’re not ready to tackle something as extreme as the projects I’ve described, there are still places where you can adjust your approach based on the experience of ultralearners and backed by the research from cognitive science.

Although the ultralearners are an extreme group of people, this approach to things holds potential for normal professionals and students. What if you could create a project to quickly learn the skills to transition to a new role, project, or even profession? What if you could master an important skill for your work, as Eric Barone did? What if you could be knowledgeable about a wide variety of topics, like Roger Craig? What if you could learn a new language, simulate a university degree program, or become good at something that seems impossible to you right now?

Ultralearning isn’t easy. It’s hard and frustrating and requires stretching outside the limits of where you feel comfortable. However, the things you can accomplish make it worth the effort. Let’s spend a moment trying to see what exactly ultralearning is and how it differs from the most common approaches to learning and education. Then we can examine what the principles are that underlie all learning, to see how ultralearners exploit them to learn faster.

CHAPTER 2

Why Ultralearning Matters

What exactly is ultralearning? While my introduction to the eclectic group of intense autodidacts started with seeing examples of unusual learning feats, to go forward we need something more concise. Here’s an imperfect definition:

ULTRALEARNING: A strategy for acquiring skills and knowledge that is both self-directed and intense.

First, ultralearning is a strategy. A strategy is not the only solution to a given problem, but it may be a good one. Strategies also tend to be well suited for certain situations and not others, so using them is a choice, not a commandment.

Second, ultralearning is self-directed. It’s about how you make decisions about what to learn and why. It’s possible to be a completely self-directed learner and still decide that attending a particular school is the best way to learn something. Similarly, you could “teach yourself” something on your own by mindlessly following the steps outlined in a textbook. Self-direction is about who is in the driver’s seat for the project, not about where it takes place.

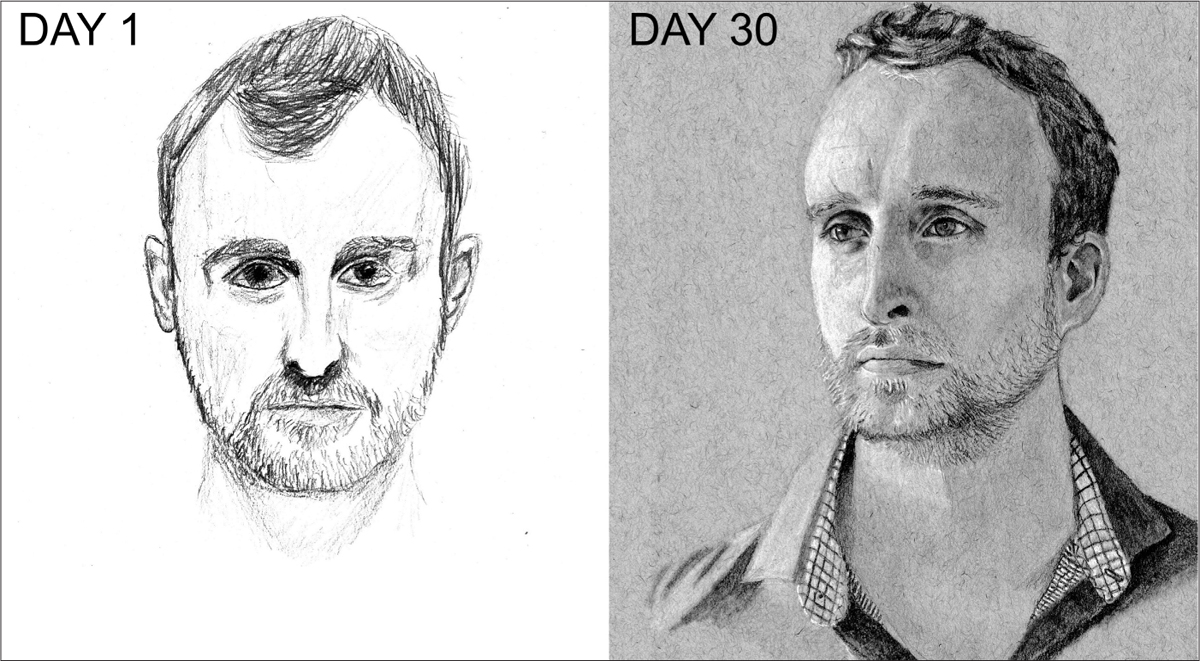

Finally, ultralearning is intense. All of the ultralearners I met took unusual steps to maximize their effectiveness in learning. Fearlessly attempting to speak a new language you’ve just started to practice, systematically drilling tens of thousands of trivia questions, and iterating through art again and again until it is perfect is hard mental work. It can feel as though your mind is at its limit. The opposite of this is learning optimized for fun or convenience: choosing a language-learning app because it’s entertaining, passively watching trivia show reruns on television so you don’t feel stupid, or dabbling instead of serious practice. An intense method might also produce a pleasurable state of flow, in which the experience of challenge absorbs your focus and you lose track of time. However, with ultralearning, deeply and effectively learning things is always the main priority.

This definition covers the examples I’ve discussed so far, but in some ways it is unsatisfyingly broad. The ultralearners I’ve met have a lot more overlapping qualities than this minimal definition implies. This is why in the second part of the book I’ll discuss deeper principles that are common in ultralearning and how they can enable some impressive achievements. Before that, however, I want to explain why I think ultralearning matters—because although the examples of ultralearning may seem eccentric, the benefits of this approach to learning are deep and practical.

THE CASE FOR ULTRALEARNING

It’s obvious that ultralearning isn’t easy. You’ll have to set aside time from your busy schedule in order to pursue something that will strain you mentally, emotionally, and possibly even physically. You’ll be forced to face down frustrations directly without retreating into more comfortable options. Given this difficulty, I think it’s important to articulate clearly why ultralearning is something you should seriously consider.

The first reason is for your work. You already expend much of your energy working to earn a living. In comparison, ultralearning is a small investment, even if you went so far as to temporarily make it a full-time commitment. However, rapidly learning hard skills can have a greater impact than years of mediocre striving on the job. Whether you want to change careers, take on new challenges, or accelerate your progress, ultralearning is a powerful tool.

The second reason is for your personal life. How many of us have dreams of playing an instrument, speaking a foreign language, becoming a chef, writer, or photographer? Your deepest moments of happiness don’t come from doing easy things; they come from realizing your potential and overcoming your own limiting beliefs about yourself. Ultralearning offers a path to master those things that will bring you deep satisfaction and self-confidence.

Although the motivation behind ultralearning is timeless, let’s start by looking at why investing in mastering the art of learning hard things quickly is going to become even more important to your future.

ECONOMICS: AVERAGE IS OVER

In the words of the economist Tyler Cowen, “Average is over.” In his book of the same title, Cowen argues that because of increased computerization, automation, outsourcing, and regionalization, we are increasingly living in a world in which the top performers do a lot better than the rest.

Driving this effect is what is known as “skill polarization.” It’s well known that income inequality has been increasing in the United States over the last several decades. However, this description ignores a more subtle picture. The MIT economist David Autor has shown that instead of inequality rising across the board, there are actually two different effects: inequality rising at the top and lowering at the bottom. This matches Cowen’s thesis of average being over, with the middle part of the income spectrum being compressed into the bottom and stretched out at the top. Autor identifies the role that technology has had in creating this effect. The advance of computerization and automation technologies has meant that many medium-skilled jobs—clerks, travel agents, bookkeepers, and factory workers—have been replaced with new technologies. New jobs have arisen in their place, but those jobs are often one of two types: either they are high-skilled jobs, such as engineers, programmers, managers, and designers, or they are lower-skilled jobs such as retail workers, cleaners, or customer service agents.

Exacerbating the trends caused by computers and robots are globalization and regionalization. As medium-skilled technical work is outsourced to workers in developing nations, many of those jobs are disappearing at home. Lower-skilled jobs, which often require face-to-face contact or social knowledge in the form of cultural or language abilities, are likely to remain. Higher-skilled work is also more resistant to shipping overseas because of the benefits of coordination with management and the market. Think of Apple’s tagline on all of its iPhones: “Designed in California. Made in China.” Design and management stay; manufacturing goes. Regionalization is a further extension of this effect, with certain high-performing companies and cities making outsized impacts on the economy. Superstar cities such as Hong Kong, New York, and San Francisco have dominating effects on the economy as firms and talent cluster together to take advantage of proximity.

This paints a picture that might either be bleak or hopeful, depending on your response to it. Bleak, because it means that many of the assumptions embedded in our culture about what is necessary to live a successful, middle-class lifestyle are quickly eroding. With the disappearance of medium-skilled jobs, it’s not enough to get a basic education and work hard every day in order to succeed. Instead, you need to move into the higher-skilled category, where learning is constant, or you’ll be pushed into the lower-skilled category at the bottom. Underneath this unsettling picture, however, there is also hope. Because if you can master the personal tools to learn new skills quickly and effectively, you can compete more successfully in this new environment. That the economic landscape is changing may not be a choice any of us has control over, but we can engineer our response to it by aggressively learning the hard skills we need to thrive.

EDUCATION: TUITION IS TOO HIGH

The accelerating demand for high-skilled work has increased the demand for college education. Except instead of expanding into education for all, college has become a crushing burden, with skyrocketing tuition costs making decades of debt a new normal for graduates. Tuition has increased far faster than the rate of inflation, which means that unless you are well poised to translate that education into a major salary increase, it may not be worth the expense.

Many of the best schools and institutions fail to teach many of the core vocational skills needed to succeed in the new high-skilled jobs. Although higher education has traditionally been a place where minds were shaped and characters developed, those lofty goals seem increasingly out of touch with the basic financial realities facing new graduates. Therefore, even for those who do go to college, there are very often skill gaps between what was learned in school and what is needed to succeed. Ultralearning can fill some of those gaps when going back to school isn’t an affordable option.

Rapidly changing fields also mean that professionals need to constantly learn new skills and abilities to stay relevant. While going back to school is an option for some, it’s out of reach for many. Who has the ability to put their life on hold for years as they wade through classes that may or may not end up covering the situations they actually need to deal with? Ultralearning, because it is directed by learners themselves, can fit into a wider variety of schedules and situations, targeting exactly what you need to learn without the waste.

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter if ultralearning is a suitable replacement for higher education. In many professions, having a degree isn’t just nice, it’s legally required. Doctors, lawyers, and engineers all require formal credentials to even start doing the job. However, those same professionals don’t stop learning when they leave school, and so the ability to teach oneself new subjects and skills remains essential.

TECHNOLOGY: NEW FRONTIERS IN LEARNING

Technology exaggerates both the vices and the virtues of humanity. Our vices are made worse because now they are downloadable, portable, and socially transmissible. The ability to distract or delude yourself has never been greater, and as a result we are facing crises of both privacy and politics. Though those dangers are real, there is also opportunity created in their wake. For those who know how to use technology wisely, it is the easiest time in history to teach yourself something new. An amount of information vaster than was held by the Library of Alexandria is freely accessible to anyone with a device and an internet connection. Top universities such as Harvard, MIT, and Yale are publishing their best courses for free online. Forums and discussion platforms mean that you can learn in groups without ever leaving your home.

Added to these new advantages is software that accelerates the act of learning itself. Consider learning a new language, such as Chinese. A half century ago, learners needed to consult cumbersome paper dictionaries, which made learning to read a nightmare. Today’s learner has spaced-repetition systems to memorize vocabulary, document readers that translate with the tap of a button, voluminous podcast libraries offering endless opportunities for practice, and translation apps that smooth the transition to immersion. This rapid change in technology means that many of the best ways of learning old subjects have yet to be invented or rigorously applied. The space of learning possibilities is immense, just waiting for ambitious autodidacts to come up with new ways to exploit it.

Ultralearning does not require new technology, though. As I will discuss in the chapters to come, the practice has a long history, and many of the most famous minds could be described as having applied some version of it. However, technology offers an incredible opportunity for innovation. There are still many ways to learn things that we have yet to fully explore. Perhaps certain learning tasks could be made far easier or even obsolete, with the right technical innovation. Aggressive and efficiency-minded ultralearners will be the first to master them.

ACCELERATE, TRANSITION, AND RESCUE YOUR CAREER WITH ULTRALEARNING

The trends toward skill polarization in the economy, skyrocketing tuition, and new technology are all global. But what does ultralearning actually look like for an individual? I believe there are three main cases in which this strategy for quickly acquiring hard skills can apply: accelerating the career you have, transitioning to a new career, and cultivating a hidden advantage in a competitive world.

To see how ultralearning can accelerate the career you already have, consider Colby Durant. After graduating from college, she started work at a web development firm but wanted to make faster progress. She took on an ultralearning project to learn copywriting. After taking the initiative and showing her boss what she could do, she was able to get a promotion. By choosing a valuable skill and focusing on quickly developing proficiency, you can accelerate your normal career progression.

Learning is often the major obstacle to transitioning to the career you want to have. Vishal Maini, for instance, was comfortable in his marketing role in the tech world. But he dreamed of being more closely involved with artificial intelligence research. Unfortunately, that was a deep technical skill set that he hadn’t acquired. Through a careful six-month ultralearning project, however, he was able to develop strong enough skills that he could switch fields and get a job working in the field he wanted.

Finally, an ultralearning project can augment the other skills and assets you’ve cultivated in your work. Diana Fehsenfeld worked as a librarian for years in her native New Zealand. Facing government cutbacks and rapid technologization of her field, she was worried that her professional experience might not be enough to keep up. As a result, she undertook two ultralearning projects, one to learn statistics and the programming language R and another on data visualization. Those skills were in demand in her industry, and adding them to her background as a librarian gave her the tools to go from bleak prospects to being indispensable.

BEYOND BUSINESS: THE CALL TO ULTRALEARNING

Ultralearning is a potent skill for dealing with a changing world. The ability to learn hard things quickly is going to become increasingly valuable, and thus it is worth developing to whatever extent you can, even if it requires some investment first.

Professional success, however, was rarely the thing that motivated the ultralearners I met—including those who ended up making the most money from their new skills. Instead it was a compelling vision of what they wanted to do, a deep curiosity, or even the challenge itself that drove them forward. Eric Barone didn’t pursue his passion in solitude for five years to become a millionaire but because he wanted the satisfaction of creating something that perfectly matched his vision. Roger Craig didn’t want to go on Jeopardy! to win prize money but to push himself to compete on the show he had loved since he was a child. Benny Lewis didn’t learn languages to become a technical translator, or later a popular blogger, but because he loved traveling and interacting with the people he met along the way. The best ultra learners are those who blend the practical reasons for learning a skill with an inspiration that comes from something that excites them.

There’s an added benefit to ultralearning that transcends even the skills one learns with it. Doing hard things, particularly things that involve learning something new, stretches your self-conception. It gives you confidence that you might be able to do things that you couldn’t do before. My feeling after my MIT Challenge wasn’t just a deepened interest in math and computer science but an expansion in possibility: If I could do this, what else could I do that I was hesitant to try before? Learning, at its core, is a broadening of horizons, of seeing things that were previously invisible and of recognizing capabilities within yourself that you didn’t know existed. I see no higher justification for pursuing the intense and devoted efforts of the ultralearners I’ve described than this expansion of what is possible. What could you learn if you took the right approach to make it successful? Who could you become?

WHAT ABOUT TALENT? THE TERENCE TAO PROBLEM

Terence Tao is smart. By age two, he had taught himself to read. At age seven, he was taking high school math classes. By seventeen, he had finished his master’s thesis. It was titled “Convolution Operators Generated by Right-Monogenic and Harmonic Kernels.” After that, he got a PhD from Princeton, won the coveted Fields Medal (called by some the “Nobel Prize for mathematics”), and is considered to be one of the best mathematical minds alive today. Though many mathematicians are extreme specialists—rare orchids adapted to thrive only on a particular branch of the mathematical tree—Tao is phenomenally diverse. He regularly collaborates with mathematicians and makes important contributions to distant fields. This virtuosity caused one colleague to liken his ability to “a leading English-language novelist suddenly producing the definitive Russian novel.”

What’s more, there doesn’t seem to be an obvious explanation for his feats. He was precocious, certainly, but his success in mathematics didn’t come from aggressively overbearing parents pushing him to study. His childhood was filled playing with his two younger brothers, inventing games with the family’s Scrabble board and mah-jongg tiles, and drawing imaginary maps of fantasy terrain. Normal kid stuff. Nor does he seem to have a particularly innovative studying method. As noted in his profile in the New York Times, he coasted on his intelligence so far that, upon reaching his PhD, he fell back “on his usual test-prep strategy: last-minute cramming.” Although that approach faltered once he reached the pinnacle of his field, the fact that he breezed through classes for so long points to a powerful mind rather than some unique strategy. Genius is a word thrown around too casually, but in Tao’s case the label certainly sticks.

Terence Tao and other naturally gifted learners present a major challenge for the universality of ultralearning. If people like Tao can accomplish so much without aggressive or inventive studying methods, why should we bother investigating the habits and methods of other impressive learners? Even if the feats of Lewis, Barone, or Craig don’t reach the level of Tao’s brilliance, perhaps their accomplishments also are due to some hidden intellectual ability that normal people lack. If this were so, ultralearning might be something interesting to examine but not something you could actually replicate.

PUTTING TALENT ASIDE

What role does natural talent play? How can we examine what causes someone’s success when the shadow of intelligence and innate gifts looms over us? What do stories like Tao’s mean for mere mortals who just want to improve their capacity to learn?