полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 343, November 29, 1828

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 12, No. 343, November 29, 1828

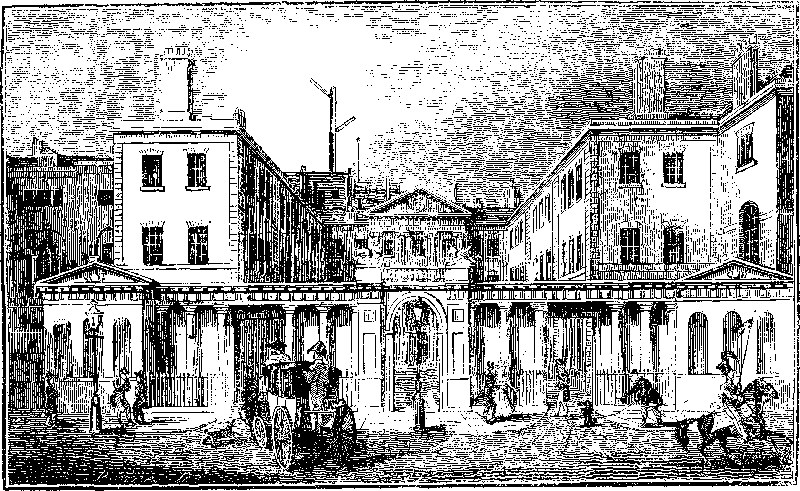

THE ADMIRALTY-OFFICE

The Admiralty Office, Whitehall, has few pretensions to architectual beauty. It is, however, to use a common phrase, a commanding pile, and its association with Britain's best bulwarks—her NAVY—renders it an interesting subject for representation.

The Admiralty-office adjoins to the north side of the Horse Guards, and was erected by Ripley, in the reign of George II., on the site of Wallingford House. It recedes from, but communicates with, the street by advancing wings, and is built principally of brick. In the centre of the main building is a lofty portico, of the Ionic order, the taste of which is not entitled to much praise. It consists of four columns, and on the entablature is an anchor in bold relief. Here are the offices, and the spacious abodes of the lords commissioners of the admiralty, together with a handsome hall, &c. On the roof of the building is a Semaphore telegraph, which communicates orders by signal to the principal ports of the empire.

But the most tasteful portion of the whole, is a stone screen, by Adams, in front of an open court, and facing the street. The style is exceedingly chaste and pleasing, and the decorations are characteristic naval emblems, finely executed. The representation of two ancient vessels in the end entablatures, merit especial notice.

Since the appointment of the Duke of Clarence to the office of lord high admiral, the Admiralty has been the town residence of his royal highness. The exterior has been repaired, and the interior in part refitted. The screen has likewise been renovated with much care, and two of the entrances considerably enlarged, but with more regard to convenience than good taste. The portion occupied by the royal duke contains a splendid suite of state rooms, within whose walls have frequently been assembled all the bravery, as well as rank, of the empire; for the interests of the noble service are too dear to his royal highness to be eclipsed by the false lights of wealth or fashion.

HUITAIN DE CLEMENT MAROT

(For the Mirror.)Plus ne suis ce que j'ay estéEt ne le scaurois jamais estre,Mon beau printemps et mon estéOnt fait le saut par la fenestre.Amour! tu as esté mon maistreJe t'ai servi sur tous les Dieux,O si je pouvois deux fois naistre,Comment je te se virois mieux!ImitationI am no more, what I have beenAnd ne'er again shall be so.My summer bright, my spring time green,Have flown out of the window.Oh love, my master thou hast been,I, first of gods, instal thee,Oh! could I e'en be born again,Thou doubly would'st enthral me.D.M.TEMPLE AT ABURY

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)There is an inconsistency in the account of Abury in No. 341, perhaps overlooked by yourself.

I would ask, how could that arrangement of the fabric, so fancifully and ingeniously described by Stukely, be intended to represent the Trinity, when the place was confessedly in existence long anterior to Christianity? nor is there any thing in the old Druidical or Bardic tenets that can be twisted to any such idea.

This Abury, with Silbury, is supposed to be the Cludair Cyfrangon, or Heaped Mound of Congregations, mentioned in the Triads, the building of which is recorded as "one of the three mighty achievements of the Isle of Britain;" and here were held the general assemblies of the Britons on religious occasions, and not at Stonehenge, as is generally supposed. This last place is decidedly more modern than the pile at Abury; the Welsh call it Gwaith Emrys, (the work of Emrys,) and it ranks as another of the mighty achievements of the Isle of Britain, the third being "the raising of the Stone of Keti," supposed to be the "Maen Ceti" at Gwyr, in Glamorganshire.

The presumption that Stonehenge is more modern than Abury is founded upon the fact that Stonehenge exhibits marks of the chisel in different parts, while the former does not. The ancient British documents give us the founder of the latter, namely, Emrys, or Ambrosius, while we are left in ignorance as to who raised the pile of Cyfrangon.

Nor was Stonehenge ever of such magnitude as Abury, the diameter of the former being 99 feet, whilst the latter was 1,400; the largest stones of the former weigh 30 tons, but the latter weigh 100 tons!

Gwaith Emrys was possibly more for political than religious assemblies. Here was held the meeting of the Britons and Saxons, when the Plot of the Long Knives (Twyll y Cyllyll Hirion) was consummated, and the flower of the British chiefs treacherously destroyed by their pretended friends.

Different authors have strenuously contended for giving the honour of supremacy to either of these places over both Britain and Gaul, in the days of Druidism; but Rowlands has industriously placed its chief seat in Anglesey.

LEATHART.TRANSLATED EPITAPH

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)Quod fuit esse quod est, quod non fuit esse quod esse,Esse quod est non esse, quod est non, erit esse.As a translation of this curious epitaph (in Lavenham churchyard) which is formed out of two Latin words, has been requested from some of your readers, I send the following:—

What John Giles has beenIs what he is, (a bachelor.)What he has not been,Is what he is, (a corpse.)To be what he isIs not to be, (a living creature.)He will have to beWhat he is not. (dust.)JOSEPH MASON.AnotherWhat we have been and what we are,The present and the time that's past,We cannot properly compareWith what we are to be at last.Tho' we ourselves have fancied forms,And beings that have never been,We unto something shall be turned—Which we have not conceived or seen.G.H.MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS

(For the Mirror.)The ensuing letter, though very short, discloses one or two instances connected with a subject of unfading interest—the death of Mary Queen of Scots. It need hardly be stated, says an able writer on this subject, that Queen Elizabeth's conduct with respect to the execution of Mary was a mixture of unrelenting cruelty, despicable cowardice, and flagitious hypocrisy; that whilst it was the dearest wish of her heart to deprive her kinswoman of her existence, she attempted to remove the odium of the act from herself, by endeavouring to induce those to whose custody she was intrusted to assassinate their prisoner; that when she found she could not succeed, she commanded the warrant to be forwarded; and that when she knew it was too late to recall it, asserted that she never intended it should be carried into execution, threw herself into a paroxysm of affected rage and grief, upbraided her counsellors, and first imprisoned and then sacrificed the fortunes of her poor secretary, Davison, one of her most virtuous servants, as a victim to her own fame, and the resentment of the King of Scots. These damning facts in the character of Elizabeth are too well known to require to be dilated on; they have eclipsed the few noble actions of her life, and remain indelible spots on her reputation as a woman and a sovereign. But we learn from this letter the humiliating effects made by her ministers to appease her fury, and her implacable resolution to overwhelm the unfortunate Davison with the effect of her assumed, or perhaps real repentance. In his apology, that statesman informs us, that on the Friday after Mary's execution, namely, on the 10th of February, arriving at the court he learnt the manner in which the queen had expressed herself relative to the event; but being advised to "absent himself for a day or two," and being, moreover, extremely ill, he left the court, and returned to London. Woolley's communication being dated on Sunday, (the manuscript is so excessively badly written as to be almost illegible,) shows that Elizabeth did not summon her council, and evince her displeasure at their conduct, until Saturday, the 13th of February, two days after she was informed of Mary's fate. Davison had been attacked with a stroke of the palsy shortly before, and all he says of his committal is, that he was not sent to the Tower until Tuesday the 14th, on account of his illness; though some days previous (probably on Saturday the 10th) the queen assembled her council.

This letter also exhibits a specimen of Leicester's characteristic meanness; for notwithstanding that he was a party to the act of forwarding the warrant for Mary's death, as his name occurs among those of the council who signed the letters to the Earl of Shrewsbury, the earl marshal, and to the Earl of Kent, both of which were dated on the 3rd of February, 1586-7, commanding them to cause it to be put into execution, he took care to withdraw from court before Elizabeth performed the roll, which has so justly excited the scorn of posterity. It may be also remarked, as another example of the official duplicity of the period, that Sir Francis Walsingham likewise affected not to have been concerned in the affair of dispatching the warrant, as in his letter to Lord Thulstone, the secretary to King James, dated at Greenwich, on the 4th of March, 1586-7, less than a month afterwards, he says, "Being absent from court when the late execution of the queen, your sovereign mother, happened," though we find that he signed both the letters just mentioned.

G.B.A Letter from John Woolley, clerk of the Council in the time of Elizabeth, to the Earl of Leicester.

To the Righte Honorable my singular good the Earle of Leycester, one of her Maties Most Honorable Privie Councell.

RYGHTE Honorable and my moste especiall goode Lorde,—It pleased her M'tye yesterday night to call the lord treasurer and other of her councell before her into her withdrawing chamber, where she rebuked us all exceedingly, from our concealing from her our proceeding in the Queen of Scott's case; but her indignation particularlye lyghteth most upon my lord treasurer and Mr. Davison, who called us togeather, and delivered the commissione, for she protesteth she gave expresse commandement to the contrarye, and therefore hath taken order for the committing of Mr. Secretary Davison to the Tower, iff she contenew in the mynd she was yeterday night, albeit we all kneeled upon our knees to praye her to the contrarye.

I think your lordship happy to be absent from these broiles, and thought it my dewtye to lett you understand them; and so in haste I humblye take my leave.—At the Courte, this present Sunday,1 1586.

Your lordship's ever most bounden,

J. WOOLLEY.P.S. I have oftentimes sent unto John, your old servante, Mr. Norld, to pray humbly your lordship's orders for the ordering of his case; he hath been long in prisone, and desireth your lordship's orders for the hearing of his case, which it may please your lordship to express unto me.—Cottonian MSS. Caligula, c. ix. fol. 168, (Original.)

The Topographer

A VISIT TO STUDLEY PARK AND FOUNTAINS ABBEY, YORKSHIRE

With a Notice of the Roman Military Road, leading from Aldborough (the Isurium of the Romans,) to the North"Yet still thy turrets drink the lightOf summer evening's softest ray;And ivy garlands, green and bright,Still mantle thy decay;And calm and beauteous, as of old,Thy wand'ring river glides in gold."A.A. WATTS.Among the most attractive scenes of northern Yorkshire is Studley Park, renowned for the richness of its sylvan scenery, which embosoms the noble ruin of Fountains Abbey.

For the date of my visit to this Arcadia, I must refer the reader to that season of life when the pure source of thought and feeling is untainted by the world. It is eleven miles from my home to Studley Park, five of which I walked in the twilight of a summer's evening, and slept at a little cottage by the way. The day had been sultry, and the moon rose slowly over the mounds of Maiden Bower, once the site of the noble mansion of the Percys, now destroyed and desolate;2 and fell in dreary softness on tower and wood, illumining the sable firs of Newby Park, and throwing another lustre on the gaudy "gowans" that decked the adjacent meadow. Here was a scene for the poetic sympathy of youth:

"That time is past,And all its giddy rapture;Yet not for this faint I, nor mourn;Other gifts have followed; for such lossI would believe, abundant recompense."WORDSWORTH.The morning found me, after an early breakfast, on the road to Studley Park. Now there are some "moods of my own mind" in which I detest all vehicles of conveyance, when on an excursive tour to admire the antique and picturesque.—Thus what numerous attractions are presented to us, sauntering along the woody lane on foot, which are lost or overlooked in the velocity of a drive! On the declivity of a meadow, inviting our reflection, rises a little Saxon church, grey with antiquity, and solemnized by its surrounding memorials of "Here lies."—Across the heath, encircled with fences of uncouth stones, stands a stern record of feudal yore; at the next turn peeps the rectory, encircled with old firs, trained fruit trees, and affectionate ivy; beneath yon darkened thickets rolls the lazy Ure, expanding into laky broadness; and, beyond yon western woods, which embower the peaceful hamlet, are seen the "everlasting hills," across which the enterprising Romans constructed their road. I next passed the boundaries of Newby Park, the property of Lord Grantham. Here beneath enormous beeches were clustering the timid deer, "in sunshine remote;" and the matin songs of birds were sounding from the countless clumps which skirt this retreat. Within that solitude had I enjoyed the society of a brother, alas, now no more! and yet the landscape wore the same sunny smile as when I carved his name on the towering obelisk before him. I felt that sorrow so exquisitely described by Burns:

"How can ye bloom so fresh and fair;How can ye chant, ye little birds,And I so weary, fu' o' care."Leaving Rainton, a sudden rise brings you to the Roman Military Road, leading from Aldborough,3 the Isurium of the Romans, to Inverness, in Scotland. This road was repaired by the Empress Heleanae, and hence the corruption, from her name, of Learning Lane, its present designation. It was laid by the Romans, with stones of immense size, which have frequently been dug up. The Via Appia, at Rome, which has lasted 1,800 years, resembles it in construction. Raised considerably above the level of the country which it crosses, it is an object of wonder and interest even to the illiterate, on account of the continuous perspective it presents; there being no bend in it for several miles. Traversing this noble monument of art, how are we led to think on the "strange mutations" which have overthrown kings and kingdoms in the period of its duration, whilst the road remains "like an eternity:"

ON CROSSING THE ROMAN MILITARY ROAD, LEADING FROM ISURIUM TO THE NORTH

O'er classic ground my humble feet did plod,My bosom beating with the glow of song;And high-born fancy walk'd with me along,Treading the earth Imperial Caesar trod.A thousand rural objects on the wayHad been my theme-but far-off years arose,When ancient Britain bow'd beneath her foes,Adding resplendence to great Caesar's day:When sounds of Roman arms through valley rung,And rose that glorious morn upon our isle,No night can hide, or cloud conceal its smile,That dazzling morn, which out of darkness sprung.Enduring cenotaph of Roman fame—More than this record of their mighty name!I reached the ancient town of Ripon as the bells were merrily ringing in the towers of its old collegiate minster, for it was the anniversary of its patron saint, St. Wilfred. After refreshment, and a walk of three miles, I arrived at Studley Park. The fairy effect produced on entering this beautiful retreat is almost indescribable. We suddenly exchange the field and forest scenery for all the poetry of prospect. On the right is a declivity clothed with laurel, and stretching far away; and on the left a lofty and well trimmed fence of laurel, forms a screen or curtain to the valley beneath; the sighing of distant woods and the dashing of waterfalls, break on the enraptured ear, and cause the anxious eye to long for some opening in the verdant shroud. Anon the valley is seen; and through an aperture in the laurel wall, cut in imitation of a window, breaks as sweet a scene as ever Claude immortalized! Unwilling to hazard a formal description, I will merely attempt an outline. Far below, the silver waters of the Skell meander softly amongst statues of tritons, throwing up innumerable fountain streams. These are masterly executions after the ancient sculptors, and give the scene an air of Grecian classicality. Around these triumphs of art, rise lofty woods of graceful birch, varied by dark fir, and interspersed with erections of Roman and Gothic design. It is in the contemplation of these beauties that fancy recalls the mythology of rocky woods, peopled with Dryads and Fauns. Passing by a circuitous path to the other side of this Eden, by sloping walks shaded with ilex, ancient oak, sycamore, cypress, and bay, we have a view of the extent of the valley, terminating with the ruins of Fountains Abbey, and flanked by rocks, wildly overgrown with shrubs; and before us, seen more distinctly, are the statues of Hercules and Antaeus, and a Dying Gladiator—the Temple of Piety, in which are bronze busts of Titus Vespasian and Nero, and a fine bas-relief of the Grecian Daughter. In front of this temple the water assumes a variety of fantastical forms, ornamented at different points by statues of Neptune, Bacchus, Roman Wrestlers, Galatea, &c. The banqueting-house contains a Venus de Medicis, and a painting of the Governor of Surat, on horseback, in a Turkish habit; on the front of this building are spirited figures of Envy, Hatred, and Malice. From the octagon tower, Mackershaw Lodge and Wood are seen to great advantage; and from the Gothic temple, the dilapidated abbey is an object of striking solemnity; whilst an opening in the distance shows the venerable towers of Ripon Minster.

Wandering eastward, we arrive at the precincts of Fountains Abbey, which gradually presents its monastic turrets midway in a dell, skirted by hills crowned with trees, and varied by rocky slopes to the brook. This abbey was founded in consequence of the disgust which certain monks of the Benedictine order at St. Mary's, York, had imbibed against their relaxed discipline; when struck with the famed austerities of the monks of Rievaulx, they left their abode, and retired to this valley, under the shade of seven yew trees, six of which were (in 1818) standing. The abbey was destroyed in the reign of Stephen, and rebuilt in 1204.4 The present ruin is celebrated for the sublimity of its architecture, many parts of which are as perfect as when first erected. The tower is 160 feet in height, and is a fine specimen of Gothic, in its best taste. It may with safety be asserted, that no church or abbey in England can boast of such an elegant elevation. The cloisters, 270 feet in length, and divided by 19 pillars and 20 arches, extend across the rivulet, which is arched over to support them; and near to the south end is a large circular stone basin. This almost subterranean solitude is dimly lighted by lancet windows, which are partially obscured by oaks, beeches, and firs; and the gloom is heightened by the brook beneath, which may be seen stretching its way through the broken arches. The only tomb in the church is that of a cross-legged knight, which lies near the grand tower, and represents one of the Mowbrays, who died at Ghent, in 1297. Near the altar is a stone coffin, in which, according to Dugdale, Lord Henry Percy was interred in 1315. Contiguous to the church is an extensive quadrangular court, which has been converted into a flower garden. On the east side is a line of beautiful arches, under one of which is the entrance to the chapter-house, a weed-grown solitude of deadly silence—

"Where the full-voiced choirLie, with their hallelujahs, quench'd like fire."In 1791, by the removal of some fragments of ruin in the chapter-house, the sepulchres of several of the abbots were discovered; but the inscriptions were obliterated. Over the chapter-house were the library and scriptorium. The architecture or Fountains Abbey is mixed; in some parts are seen the sharp-pointed windows, in others the circular arches. The great eastern window is indescribably magnificent, being 23 feet in width. There has been a central tower, which has long since fallen to decay. The sanctum sanctorum is 131 feet in length; over one of its eastern windows is the figure of an angel holding a scroll, dated 1283. The total length of the church is 358 feet. On the north side of the quadrangular court is the refectory, which was supported by large pillars, and adjoining it is the reading gallery, where portions of the Scriptures were delivered to the monks whilst at their meals; by the side of it are the kitchen and scullery, the former remarkable for its spacious arched fire place. Over the refectory was the dormitory, which contained 40 cells; and under the crumbling steps leading to it is the porter's lodge. Near to the refectory are the remains of the abbot's chambers.

But adieu to the waning glory of Fountains Abbey and the receding towers of Ripon Minster, while retracing my path of yesterday morning. I must linger awhile on the Roman way, where antiquity maintains her supremacy in spite of the war of time, and where the earth looks immutable. Now the groves of Newby Park re-appear with their "sylvan majesty," creating unutterable sympathies; for the wind that bows the surrounding branches moves me to weep for that romantic spirit whose ashes moulder on the shores of India, where

"When the sun's noon-glory crests the wave,He shines, without a shadow on his grave."* * H.THE ANECDOTE GALLERY

PALEY

Paley would employ himself in his Natural Theology, and then gather his peas for dinner, very likely gathering some hint for his work at the same time. He would converse with his classical neighbour, Mr. Yates, or he would reply to his invitation that he could not come, for that he was busy knitting. He would station himself at his garden wall, which overhung the river, and watch the progress of a cast-iron bridge in building, asking questions of the architect, and carefully examining every pin and screw with which it was put together. He would loiter along a river, with his angle-rod, musing upon what he supposed to pass in the mind of a pike when he bit, and when he refused to bite; or he would stand by the sea-side, and speculate upon what a young shrimp could mean by jumping in the sun.

With the handle of his stick in his mouth, he would move about his garden in a short hurried step, now stopping to contemplate a butterfly, a flower, or a snail, and now earnestly engaged in some new arrangement of his flower-pots.

He would take from his own table to his study the back-bone of a hare, or a fish's head; and he would pull out of his pocket, after a walk, a plant or stone to be made tributary to an argument. His manuscripts were as motley as his occupations; the workshop of a mind ever on the alert; evidences mixed up with memorandums for his will; an interesting discussion brought to an untimely end by the hiring of servants, the letting of fields, sending his boys to school, reproving the refractory members of an hospital; here a dedication, there one of his children's exercises—in another place a receipt for cheap soup. He would amuse his fire side by family anecdotes:—how one of his ancestors (and he was praised as a pattern of perseverance) separated two pounds of white and black pepper which had been accidentally mixed—patiens pulveris, he might truly have added; and how, when the Paley arms were wanted, recourse was had to a family tankard which was supposed to bear them, but which he always took a malicious pleasure in insisting had been bought at a sale—