Полная версия

Bad Blood

BAD BLOOD

Lorna Sage

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2000

Copyright © Lorna Sage 2000

Introduction copyright © Frances Wilson, 2020

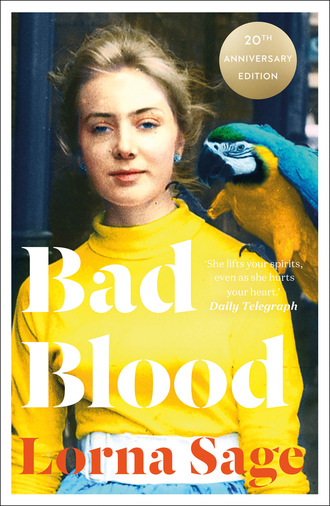

Cover photograph: Lorna Sage aged 14

‘All Shook Up’ Words and Music by Otis Blackwell and Elvis Presley © 1957 by Shalimar Music, Inc. – assigned to Elvis Presley Music, Inc., all rights administered by R & H Music and Williamson Music – All Rights Reserved. Lyric reproduced by kind permission of Carlin Music Corp., London NW1 8BD. ‘(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear’ Words and Music by Kal Mann and Bernie Lowe © 1957 Gladys Music – all rights administered by R & H Music and Williamson Music – All right Reserved. Lyric reproduced by kind permission of Carlin Music Corp., London NW1 8BD. ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ Words and Music by Mae Boren Axion, Tomy Durden and Elvis Presley © 1956, Tree Publishing Co. Inc., US. Reproduced by kind permission of EMI Music Publishing Ltd, London WC2H 0EA.

Lorna Sage asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9781841150437

Ebook Edition © 2020 ISBN: 9780007374281

Version: 2020-08-14

Praise for Bad Blood:

‘In a class of its own … It is a measure of her achievement that she can turn the peculiarities of her own past – and they are peculiar – into a narrative that speaks for the whole of post-war Britain … This is not just an exquisite personal memoir, it is a vital piece of our collective past’

Daily Telegraph

‘A wonderful book. Women need this kind of book but perhaps men need it more, to give the sort of understanding which we still lack of how girls actually grow up’

Margaret Forster

‘This could have been the saddest book you have ever read, but because of Lorna Sage’s relish in the details, her exuberant celebration of the vitality of this clever, surviving girl, it is as enjoyable a book as I remember reading’

Doris Lessing

‘[A] rich, justly acclaimed autobiography … this almost perfect memoir is a tribute to imperfection’

Independent

‘Lorna Sage has always been among the most acute literary critics of her generation, and this book shows why: because she writes so well herself, with an honesty equal to a story as painful as this. She has transmuted a bad dream into a book of classic poise. This is not a book for children, but neither was her childhood’

Clive James

‘Speak, Memory! Lorna Sage’s memoir is magnificent and quite impossible to lay aside. What a book for this country now. She makes Hanmer, Whitchurch, the shop, the ailing haulage business, the lightless houses, the mad relations, into the real ancestral England, from which the English have ever since been on the run’

Jonathan Raban

Dedication

For Sharon and Olivia

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Praise for Bad Blood

Dedication

Introduction by Frances Wilson

PART ONE

I The Old Devil and His Wife

II School

III Grandma at Home

IV The Original Sin

V Original Sin, Again

VI Death

PART TWO

VII Council House

VIII A Proper Marriage

IX Sticks

X Nisi Dominus Frustra

XI Family Life

XII Family Life Continued

PART THREE

XIII All Shook Up

XIV Love – Fifteen

XV Sunnyside

XVI To the Devil a Daughter

XVII Crosshouses

XVIII Eighteen

Afterword

About the Author

About the Publisher

Introduction By Frances Wilson

Lorna Sage, who died of emphysema on 11 January 2001, lived just long enough to see a finished copy of her memoir and to know that it had won the Whitbread Prize for Biography. Since then, Bad Blood has been included in the Guardian’s 100 Best Books of the 21st Century, making it that rare thing: an instant classic. It is still, twenty years after publication, the most powerful coming-of-age story I have read, and the most memorable portrayal of the theatre that is family life. ‘There is something cloying and close about living in a proper family,’ Sage writes, ‘that has always brought out the worst in me’. That same claustrophobia, however, brought out the best in her as a writer.

A Professor of English at the University of East Anglia, Lorna Sage straddled the borders of Grub Street and academe and Bad Blood is about borders and border crossings. She crossed from childhood to adolescence in a Welsh border town called Hanmer, which is so small, her schoolteacher gleefully revealed, that it wasn’t even on the map (in 2001, the population was 726). Hanmer was ‘a time warp’ and Lorna, born in 1943, grew up in what she calls ‘an enclave of the nineteenth century’, where the gravedigger’s name was Mr Downward and the blacksmith who lived by the mere was called Mr Bywater. She would straddle the borders of the pre- and the post-war worlds when she joined the first generation of women to go to university, and there added her voice to second-wave feminism.

Lorna was raised by her mother and her grandparents in the local vicarage, and her first nine years are recorded in the language of a gothic novel. The hero is Lorna’s bookish grandfather, the Vicar of St Chad’s, clad in black skirts with a scar running down his hollow cheek, and the villain is her grandmother Hilda, four foot ten and lethal with the carving knife when her husband comes home pissed. The book’s opening image, with Lorna ‘hanging on’ to her grandfather’s skirts as they flap in the wind on the churchyard path, propels us instantly into the comedy of her storytelling; I imagine her suspended in the air like one of those weightless figures by Quentin Blake who are always on the move, buoyed along on a raft of their own innocence. If Lorna turned her grandfather into a hero, he ensured her role as a heroine by naming her after Lorna Doone in R. D. Blackmore’s romance. By the time she was four, she had been taught by him to read; Lorna was, from the start, her grandfather’s creature and her lifetime in books informs the subtlety and irony of her prose. Lorna’s childhood world, filtered through her adult sensibility, is a literary echo chamber.

The vicarage is itself a place of border controls, with her grandparents occupying different territories. Hilda, in one wing, pines for her home town of Tonypandy where her family have status and a shop, while her husband in his study, Lorna later learns, pines for other women, first a local nurse referred to as MB, and then a seventeen-year-old friend of his daughter, called Marj. Discovering his affairs, Hilda blackmails him for a portion of his stipend every quarter. Lorna’s father is absent for her early years and her mother, Valma (also named by the vicar), is pictured as ‘a shy, slender wraith’ sweeping the hearth like Cinderella while plates and pans fly over her head.

The vicar, depending on whose side you are on, is either a faithless, cheating wastrel or a Romantic melancholic. He reminds me of Patrick Brontë, the half-mad father of the Brontë sisters who let off steam by sawing the legs off chairs, shredding his daughters’ dresses and firing loaded guns from the kitchen door. Lorna describes the vicar’s ‘defiant’ and ‘outrageous’ glamour as shamanistic, vampiric, Byronic; his past followed him, she says, ‘like a long, glamorous, sinister shadow’ and this same shadow hangs over these pages because the Vicar of St Chad’s is the spirit of Bad Blood. At the book’s centre are the diaries he kept in 1933 and 1934, in which he records his indiscretions and reveals, as Lorna wonderfully puts it, his ‘distinguishing trait’ to be ‘pride in his own awfulness’. He wrote a diary, she concludes, because he saw himself as a writer, but also to redeem his life from ‘the squalor of insignificance’. The squalor of insignificance: the phrase is painfully good, but then every line of Bad Blood is quotable. Lorna’s grandparents, for example, buried in same plot, are ‘rotting together for eternity, one flesh at last after a lifetime’s mutual loathing.’ The best term to describe Sage’s tone in these passages might be horrid laughter.

The Vicar was not, of course, a glamorous figure to anyone other than his granddaughter. A lonely and bitter man exiled in an illiterate parish, it is striking that it is his story and not her grandmother’s that moved her because, in her life as an academic, Lorna reclaimed the stories of women and not men, writing seminal studies of Angela Carter and Doris Lessing, and editing the vast Cambridge Guide to Women’s Writing in English.

When her grandfather dies in 1952, the genre of Bad Blood shifts from the gothic to what Lorna calls ‘socialist realism’. The family move from the spell-binding squalor of the vicarage to the wipeable surfaces of a 1950s council house, Lorna’s father returns to civilian life and a baby brother is born. There is also a subtle shift of class, one of several that Lorna will experience as she is propelled forwards. The newly formed nuclear unit is organised around a profoundly domestic mother who lacks, to a spectacular degree, any domestic skills and whose dominating feature is her fear of food. Could Valma have been anorexic? Sage doesn’t say, but the question hangs in the air: she had a horror of swallowing and so picked all day, occasionally bingeing on onions.

Socialist realism is replaced, in the book’s final section, by a parody of romance when the family move upwards again, this time to a large house with a gravel drive bought with the proceeds of Hilda’s blackmail campaign. The author’s sense of her life as a narrative is now so strongly ingrained that when her schoolteacher gives her some hairgrips for her unruly locks, Lorna concedes that ‘I was letting my hair down too early in the plot’. The plot twist, when it comes, is as much as surprise to her as it is to us.

There are several more borders to cross before the story draws to its close with Lorna entering adulthood against the grain. In the age of the Beatles and the Chatterley Trial she reads English at Durham University, a place whose buildings, ‘angular, hard-edged, ill-lit and draughty’, remind her of the vicarage. Here she meets the brilliant Nicholas Brooke (author of Horrid Laughter in Jacobean Tragedy) who will go on to become her colleague at the University of East Anglia. With his ‘theatricality’, ‘bitterness’, ‘cradled cigarette’ and ‘flapping black gown’, Professor Brooke is the image of Lorna’s first mentor, the man whose skirts she would hang onto as they flapped in the wind on the churchyard path. Still moving forward, she is now ‘part of the shape of things to come.’

I The Old Devil and His Wife

Grandfather’s skirts would flap in the wind along the churchyard path and I would hang on. He often found things to do in the vestry, excuses for getting out of the vicarage (kicking the swollen door, cursing) and so long as he took me he couldn’t get up to much. I was a sort of hobble; he was my minder and I was his. He’d have liked to get further away, but petrol was rationed. The church was at least safe. My grandmother never went near it – except feet first in her coffin, but that was years later, when she was buried in the same grave with him. Rotting together for eternity, one flesh at the last after a lifetime’s mutual loathing. In life, though, she never invaded his patch; once inside the churchyard gate he was on his own ground, in his element. He was good at funerals, being gaunt and lined, marked with mortality. He had a scar down his hollow cheek too, which Grandma had done with the carving knife one of the many times when he came home pissed and incapable.

That, though, was when they were still ‘speaking’, before my time. Now they mostly monologued and swore at each other’s backs, and he (and I) would slam out of the house and go off between the graves, past the yew tree with a hollow where the cat had her litters and the various vaults that were supposed to account for the smell in the vicarage cellars in wet weather. On our right was the church; off to our left the graves stretched away, bisected by a grander gravel path leading down from the church porch to a bit of green with a war memorial, then – across the road – the mere. The church was popular for weddings because of this impressive approach, but he wasn’t at all keen on the marriage ceremony, naturally enough. Burials he relished, perhaps because he saw himself as buried alive.

One day we stopped to watch the gravedigger, who unearthed a skull – it was an old churchyard, on its second or third time around – and grandfather dusted off the soil and declaimed: ‘Alas poor Yorick, I knew him well …’ I thought he was making it up as he went along. When I grew up a bit and saw Hamlet and found him out, I wondered what had been going through his mind. I suppose the scene struck him as an image of his condition – exiled to a remote, illiterate rural parish, his talents wasted and so on. On the other hand his position afforded him a lot of opportunities for indulging secret, bitter jokes, hamming up the act and cherishing his ironies, so in a way he was enjoying himself. Back then, I thought that was what a vicar was, simply: someone bony and eloquent and smelly (tobacco, candle grease, sour claret), who talked into space. His disappointments were just part of the act for me, along with his dog-collar and cassock. I was like a baby goose imprinted by the first mother-figure it sees – he was my black marker.

It was certainly easy to spot him at a distance too. But this was a village where it seemed everybody was their vocation. They didn’t just ‘know their place’, it was as though the place occupied them, so that they all knew what they were going to be from the beginning. People’s names conspired to colour in this picture. The gravedigger was actually called Mr Downward. The blacksmith who lived by the mere was called Bywater. Even more decisively, the family who owned the village were called Hanmer, and so was the village. The Hanmers had come over with the Conqueror, got as far as the Welsh border and stayed ever since in this little rounded isthmus of North Wales sticking out into England, the detached portion of Flintshire (Flintshire Maelor) as it was called then, surrounded by Shropshire, Cheshire and – on the Welsh side – Denbighshire. There was no town in the Maelor district, only villages and hamlets; Flintshire proper was some way off; and (then) industrial, which made it in practice a world away from these pastoral parishes, which had become resigned to being handed a Labour MP at every election. People in Hanmer well understood, in almost a prideful way, that we weren’t part of all that. The kind of choice represented by voting didn’t figure large on the local map and you only really counted places you could get to on foot or by bike.

The war had changed this to some extent, but not as much as it might have because farming was a reserved occupation and sons hadn’t been called up unless there were a lot of them, or their families were smallholders with little land. So Hanmer in the 1940s in many ways resembled Hanmer in the 1920s, or even the late 1800s except that it was more depressed, less populous and more out of step – more and more islanded in time as the years had gone by. We didn’t speak Welsh either, so that there was little national feeling, rather a sense of stubbornly being where you were and that was that. Also very un-Welsh was the fact that Hanmer had no chapel to rival Grandfather’s church: the Hanmers would never lease land to Nonconformists and there was no tradition of Dissent, except in the form of not going to church at all. Many people did attend, though, partly because he was locally famous for his sermons, and because he was High Church and went in for dressing up and altar boys and frequent communions. Not frequent enough to explain the amount of wine he got through, however. Eventually the Church stopped his supply and after that communicants got watered-down Sanatogen from Boots the chemist in Whitchurch, over the Shropshire border.

The delinquencies that had denied him preferment seemed to do him little harm with his parishioners. Perhaps the vicar was expected to be an expert in sin. At all events he was ‘a character’. To my childish eyes people in Hanmer were divided between characters and the rest, the ones and the many. Higher up the social scale there was only one of you: one vicar, one solicitor, each farmer identified by the name of his farm and so sui generis. True, there were two doctors, but they were brothers and shared the practice. Then there was one policeman, one publican, one district nurse, one butcher, one baker … Smallholders and farm labourers were the many and often had large families too. They were irretrievably plural and supposed to be interchangeable (feckless all), nameable only as tribes. The virtues and vices of the singular people turned into characteristics. They were picturesque. They had no common denominator and you never judged them in relation to a norm. Coming to consciousness in Hanmer was oddly blissful at the beginning: the grown-ups all played their parts to the manner born. You knew where you were.

Which was a hole, according to Grandma. A dead-alive dump. A muck heap. She’d shake a trembling fist at the people going past the vicarage to church each Sunday, although they probably couldn’t see her from behind the bars and dirty glass. She didn’t upset my version of pastoral. She lived in a different dimension, she said as much herself. In her world there were streets with pavements, shop windows, trams, trains, teashops and cinemas. She never went out except to visit this paradise lost, by taxi to the station in Whitchurch, then by train to Shrewsbury or Chester. This was life. Scented soap and chocolates would stand in for it the rest of the time – most of the time, in fact, since there was never any money. She’d evolved a way of living that resolutely defied her lot. He might play the vicar, she wouldn’t be the vicar’s wife. Their rooms were at opposite ends of the house and she spent much of the day in bed. She had asthma, and even the smell of him and his tobacco made her sick. She’d stay up late in the evening, alone, reading about scandals and murders in the News of the World by lamplight among the mice and silverfish in the kitchen (she’d hoard coal for the fire up in her room and sticks to relight it if necessary). She never answered the door, never saw anyone, did no housework. She cared only for her sister and her girlhood friends back in South Wales and – perhaps – for me, since I had blue eyes and blonde hair and was a girl, so just possibly belonged to her family line. She thought men and women belonged to different races and any getting together was worse than folly. The ‘old devil’, my grandfather, had talked her into marriage and the agony of bearing two children, and he should never be forgiven for it. She would quiver with rage whenever she remembered her fall. She was short (about four foot ten) and as fat and soft-fleshed as he was thin and leathery, so her theory of separate races looked quite plausible. The rhyme about Jack Sprat (‘Jack Sprat would eat no fat, / His wife would eat no lean, / And so between the two of them / They licked the platter clean’) struck me, when I learned it, as somehow about them. Looking back, I can see that she must have been a factor – along with the booze (and the womanising) – in keeping him back in the Church. She got her revenge, but at the cost of living in the muck heap herself.

Between the two of them my grandparents created an atmosphere in the vicarage so pungent and all-pervading that they accounted for everything. In fact, it wasn’t so. My mother, their daughter, was there; I only remember her, though, at the beginning, as a shy, slender wraith kneeling on the stairs with a brush and dustpan, or washing things in the scullery. They’d made her into a domestic drudge after her marriage – my father was away in the army and she had no separate life. It was she who answered the door and tried to keep up appearances, a battle long lost. She wore her fair hair in a victory roll and she was pretty but didn’t like to smile. Her front teeth were false – crowned, a bit clumsily – because in her teens, running to intervene in one of their murderous rows, she’d fallen down the stairs and snapped off her own. During these years she probably didn’t feel much like smiling anyway. She doesn’t come into the picture properly yet, nor does my father. My only early memory of him is being picked up by a man in uniform and being sick down his back. He wasn’t popular in the vicarage, although it must have been his army pay that eked out Grandfather’s exiguous stipend.

The grandparents weren’t grateful. They both felt so cheated by life, they had their histories of grievance so well worked out, that they were owed service, handouts, anything that was going. My mother and her brother they’d used as hostages in their wars and otherwise neglected, being too absorbed in each other, in their way, to spare much feeling. With me it was different: since they no longer really fought they had time on their hands and I got the best of them. Did they love me? The question is beside the point, somehow. Certainly they each spoiled me, mainly by giving me the false impression that I was entitled to attention nearly all the time. They played. They were like children, if you consider that one of the things about being a child is that you are a parasite of sorts and have to brazen it out self-righteously. I want. They were good at wanting and I shared much more common ground with them than with my mother when I was three or four years old. Also, they measured up to the magical monsters in the story books. Grandma’s idea of expressing affection to small children was to smack her lips and say, ‘You’re so sweet, I’m going to eat you all up!’ It was not difficult to believe her, either, given her passion for sugar. Or at least I believed her enough to experience a pleasant thrill of fear. She liked to pinch, too, and she sometimes spat with hatred when she ran out of words.

Domestic life in the vicarage had a Gothic flavour at odds with the house, which was a modest eighteenth-century building of mellowed brick, with low ceilings, and attics and back stairs for help we didn’t have. At the front it looked on to a small square traversed only by visitors and churchgoers. The barred kitchen window faced this way, but in no friendly fashion, and the parlour on the other side of the front door was empty and unused, so that the house was turned in on itself, against its nature. A knock at the door produced a flurry of hiding-and-tidying (my grandmother must be given time to retreat, if she was up, and I’d have my face scrubbed with a washcloth) in case the visitor was someone who’d have to be invited in and shown to the sitting-room at the back which – although a bit damp and neglected – was always ‘kept nice in case’.