полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 348, December 27, 1828

Yet, though I was to be thus abandoned by my fox-hunting friends, I was by no means to feel myself the inhabitant of a solitary world. If the sudden discovery of kindred could cheer me under my calamities, no man might have passed a gayer life. For a long succession of years I had not seen a single relative. Not that they altogether disdained even the humble hospitalities of my cottage, or the humble help of my purse; on the contrary, they liked both exceedingly, and would have exhibited their affection in enjoying them as often as I pleased.

But I had early adopted a resolution, which I recommend to all men. I made use of no disguise on the subject of our mutual tendencies. I knew them to be selfish, beggarly in the midst of wealth, and artificial in the fulness of protestation. I disdained to play the farce of civility with them. I neither kissed nor quarrelled with them; but I quietly shut my door, and at last allowed no foot of their generation inside it. They hated me mortally in consequence, and I knew it. I despised them, and I conclude they knew that too. But I was resolved that they should not despise me; and I secured that point by not suffering them to feel that they had made me their dupe. The nabob's will had not soothed their tempers; and I was honoured with their most smiling animosity.

But now, as if they were hidden in the ground like weeds only waiting for the shower, a new and boundless crop of relationship sprang up. Within the first fortnight after my return, I was overwhelmed with congratulations from east, west, north, and south; and every postscript pointed with a request for my interest with boards and public offices of all kinds; with India presidents, treasury secretaries, and colonial patrons, for the provision of sons, nephews, and cousins, to the third and fourth generation.

My positive declarations that I had no influence with ministers were received with resolute scepticism. I was charged with old obligations conferred on my grandfathers and grandmothers; and, finally, had the certain knowledge that my gentlest denials were looked upon as a compound of selfishness and hypocrisy. Before a month was out, I had extended my sources of hostility to three-fourths of the kingdom, and contrived to plant in every corner some individual who looked on himself as bound to say the worst he could of his heartless, purse-proud, and abjured kinsman.

I should have sturdily borne up against all this while I could keep the warfare out of my own county. But what man can abide a daily skirmish round his house? I began to think of retreating while I was yet able to show my head; for, in truth, I was sick of this perpetual belligerency. I loved to see happy human faces. I loved the meeting of those old and humble friends to whose faces, rugged as they were, I was accustomed. I liked to stop and hear the odd news of the village, and the still odder versions of London news that transpired through the lips of our established politicians. I liked an occasional visit to our little club, where the exciseman, of fifty years standing was our oracle in politics; the attorney, of about the same duration, gave us opinions on the drama, philosophy, and poetry, all equally unindebted to Aristotle; and my mild and excellent father-in-law, the curate, shook his silver locks in gentle laughter at the discussion. I loved a supper in my snug parlour with the choice half dozen; a song from my girls, and a bottle after they were gone to dream of bow-knots and bargains for the next day.

But my delights were now all crushed. Another Midas, all I touched had turned to gold; and I believe in my soul that, with his gold, I got credit for his asses' ears.

However, I had long felt that contempt for popular opinion which every man feels who knows of what miserable materials it is made—how much of it is mere absurdity—how much malice—how much more the frothy foolery and maudlin gossip of the empty of this empty generation. "What was it to me if the grown children of our idle community, the male babblers, and the female cutters-up of character, voted me, in their commonplace souls, the blackest of black sheep? I was still strong in the solid respect of a few worth them all."

Let no man smile when I say that, on reckoning up this Theban band of sound judgment and inestimable fidelity, I found my muster reduced to three, and those three of so unromantic a class as the grey-headed exciseman, the equally grey-headed solicitor, and the curate.

But let it be remembered that a man must take his friends as fortune wills; that he who can even imagine that he has three is under rare circumstances; and that, as to the romance, time, which mellows and mollifies so many things, may so far extract the professional virus out of excisemen and solicitor, as to leave them both not incapable of entering into the ranks of humanity.

SPIRIT of DISCOVERY

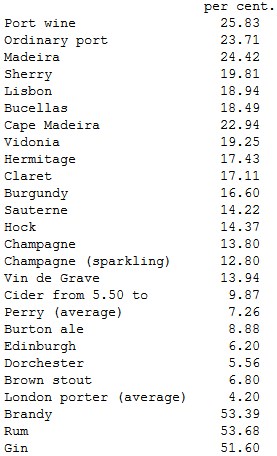

SPECIFIC GRAVITIES

TableShowing the proportion per cent, of alcohol contained in different fermented liquors.

The figures set down opposite each liquor, exhibit the quantity of alcohol per cent. by measure in each at the temperature of 60°. Port, Sherry and Madeira, contain a large quantity of alcohol; that Claret, Burgundy, and Sauterne, contain less; and that Brandy contains as much as 53 per cent. of alcohol. In a general way, we may say, that the strong wines in common use, contain as much as a fourth per cent. of alcohol.

Extraordinary Effect of HeatDuring Captain Franklin's recent voyage, the winter was so severe, near the Coppermine River, that the fish froze as they were taken out of the nets; in a short time they became a solid mass of ice, and were easily split open by a blow from a hatchet. If, in the completely frozen state, they were thawed before the fire, they revived. This is a very remarkable instance of how completely animation can be suspended in cold-blooded animals.

J.G.L.Method of Softening Cast-IronThe following method of rendering cast-iron soft and malleable may be new to some of your readers:—It consists in placing it in a pot surrounded by a soft red ore, found in Cumberland and other parts of England, which pot is placed in a common oven, the doors of which being closed, and but a slight draught of air permitted under the grate; a regular heat is kept up for one or two weeks, according to the thickness and weight of the castings. The pots are then withdrawn, and suffered to cool; and by this operation the hardest cast metal is rendered so soft and malleable, that it may be welded together, or, when in a cool state, bent into almost any shape by a hammer or vice.

W.G.C.Washing Salads, Cresses, &c.A countryman was seized with the most excruciating pain in his stomach, and which continued for so long a period, that his case became desperate, and his life was even despaired of. In this predicament, the medical gentleman to whom he applied administered to him a most violent emetic, and the result was the ejection of the larva, and which remained alive for a quarter of an hour after its expulsion. Upon questioning the man as to how it was likely that the insect got into his stomach, he stated that he was exceedingly fond of watercresses, and often gathered and eat them, and, possibly, without taking due care, in freeing them from any aquatic insects they might hold. He was also in the frequent habit of lying down and drinking the water of any clear rivulet when he was thirsty; and thus, in any of these ways, the insect, in its smaller state, might have been swallowed, and remained gradually increasing in size until it was ready for the change into the beetle state; at times, probably, preying upon the inner coat of the stomach, and thus producing the severe pains complained of by the sufferer.

We are surprised we do not hear more of the effects of swallowing the eggs or larva of insects, along with raw salads of different kinds. We would strongly recommend all families who can afford it, to keep in their sculleries a cistern of salt water, or, if they will take the trouble of renewing it frequently, of lime and water; and to have all vegetables to be used raw, first plunged in this cistern for a minute, and then washed in pure fresh water.—Gardener's Magazine.

Insects on TreesMr. Johnson, of Great Totham, is of opinion that smearing trees with oil, to destroy insects on them, injures the vegetation, and is not a certain remedy. He recommends scrubbing the trunks and branches of the trees every second year, with a hard brush dipped in strong brine of common salt. This effectually destroys insects of all kinds, and moss; and the stimulating influence of the application and friction is very beneficial.

MannaThe manna of the larch is thus procured:—About the month of June, when the sap of the tree is most luxuriant, it produces small white drops, of a sweet glutinous matter, like Calabrian manna, which are collected by the peasants early in the morning before the sun dissipates them.—Med. Bot.

Electricity on PlantsIt is very easy to kill plants by means of electricity. A very small shock, according to Cavallo, sent through the stem of a balsam, is sufficient to destroy it. A few minutes after the passage of the shock, the plant droops, the leaves and branches become flaccid, and its life ceases. A small Leyden phial, containing six or eight square inches of coated surface, is generally sufficient for this purpose, which may even be effected by means of strong sparks from the prime conductor of a large electrical machine. The charge by which these destructive effects are produced, is probably too inconsiderable to burst the vessels of the plant, or to occasion any material derangement of its organization; and, accordingly, it is not found, on minute examination of a plant thus killed by electricity, that either the internal vessels or any other parts have sustained perceptible injury.

STANGING

Two correspondents have favoured us with the following illustrations of this curious custom: one of them (W.H.H.) has appended to his communication a pen and ink sketch, from which the above engraving is copied:—

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)In Westmoreland this custom is thus commenced:—When it is known that a man has "fallen out" with his wife, or beaten or ill-used her, the townspeople procure a long pole, and instantly repair to his house; and after creating as much riot and confusion before the house as possible, one of them is hoisted upon this pole, borne by the multitude. He then makes a long speech opposite the said house, condemning, in strong terms, the offender's conduct—the crowd also showing their disapprobation. After this he is borne to the market-place, where he again proclaims his displeasure as before; and removes to different parts of the town, until he thinks all the town are informed of the man's behaviour; and after endeavouring to extort a fine from the party, which he sometimes does, all repair to a public-house, to regale themselves at his expense. Unless the delinquent can ill afford it, they take his "goods and chattels," if he will not surrender his money. The origin of this usage I am ignorant of, and shall be greatly obliged by any kind correspondent of the MIRROR who will explain it.

W.H.H.(To the Editor of the Mirror.)At Biggar, in Lanarkshire, as well as in several other places in Scotland, a very singular ancient practice is at times, though but rarely, revived. It is called riding the stang. When any husband is known to treat his wife extremely ill by beating her, and when the offence is long and unreasonably continued, while the wife's character is unexceptionable, the indignation of the neighbourhood, becoming gradually vehement, at last breaks out into action in the following manner:—All the women enter into conspiracy to execute vengeance upon the culprit. Having fixed upon the time when their design is to be put into effect, they suddenly assemble in a great crowd, and seize the offending party. They take care, at the same time, to provide a stout beam of wood, upon which they set him astride, and, hoisting him aloft, tie his legs beneath. He is thus carried in derision round the village, attended by the hootings, scoffs, and hisses of his numerous attendants, who pull down his legs, so as to render his seat in other respects abundantly uneasy. The grown-up men, in the meanwhile, remain at a distance, and avoid interfering in the ceremony. And it is well if the culprit, at the conclusion of the business, has not a ducking added to the rest of the punishment. Of the origin of this custom we know nothing. It is well known, however, over the country; and within these six years, it was with great ceremony performed upon a weaver in the Canongate of Edinburgh.

This custom can scarcely fail to recall to the recollection of the intelligent reader, the analogous practice among the Negroes of Africa, mentioned by Mungo Park, under the denomination of the mysteries of Mumbo Jumbo. The two customs, however, mark, in a striking manner, the different situations of the female sex in the northern and middle regions of the globe. From Tacitus and the earliest historians we learn, that the most ancient inhabitants of Europe, however barbarous their condition in other respects might be, lived on terms of equal society with their women, and avoided the practice of polygamy; but in Africa, where the laws of domestic society are different, the husbands, as the masters of a number of enslaved women, find it necessary to have recourse to frauds and disgraceful severities to maintain their authority; whereas in Europe we find, among the common people, a sanction for the women to protect each other, by severities, against the casual injustice committed by the ruling sex.

CHARLES STUART.NOTES OF A READER

CHRISTMAS SCRAPS

We have spiced our former volumes, as well as our present number, with two or three articles suitable to this jocund season; but we cannot deny ourselves the pleasure of adding "more last words." People talk of Old and New Christmas with woeful faces; and a few, more learned than their friends, cry stat nominis umbra,—all which may be very true, for aught we know or care. Swift proved that mortal MAN is a broomstick; and Dr. Johnson wrote a sublime meditation on a pudding; and we could write a whole number about the midnight mass and festivities of Christmas, pull out old Herrick and his Ceremonies for Christmasse—his yule log—and Strutt's Auntient Customs in Games used by Boys and Girls, merrily sett out in verse; but we leave such relics for the present, and seek consolation in the thousand wagon-loads of poultry and game, and the many million turkeys that make all the coach—offices of the metropolis like so many charnel-houses. We would rather illustrate our joy like the Hindoos do their geography, with rivers and seas of liquid amber, clarified butter, milk, curds, and intoxicating liquors. No arch in antiquity, not even that of Constantine, delights us like the arch of a baron of beef, with its soft-flowing sea of gravy, whose silence is only broken by the silver oar announcing that another guest is made happy. Then the pudding, with all its Johnsonian associations of "the golden grain drinking the dews of the morning—milk pressed by the gentle hand of the beauteous milk-maid—egg, that miracle of nature, which Burnett has compared to creation—and salt, the image of intellectual excellence, which contributes to the foundation of a pudding." As long as the times spare us these luxuries, we leave Hortensius to his peacocks; Heliogabalus to his dishes of cocks-combs; and Domitian to his deliberations in what vase he may boil his huge turbot. We have epicures as well as had our ancestors; and the wonted fires of Apicius and Sardanapalus may still live in St. James's-street and Waterloo-place; but commend us to the board, where each guest, like a true feeler, brings half the entertainment along with him. This brings us to notice Christmas, a Poem, by Edward Moxon, full of ingenuousness and good feeling, in Crabbe-like measure; but, captious reader, suspect not a pun on the poet of England's hearth—for a more unfortunate name than Crabbe we do not recollect.

Mr. Moxon's is a modest little octavo, of 76 pages, which may be read between the first and last arrival of a Christmas party. As a specimen, we subjoin the following:—

Hail, Christmas! holy, joyous time,The boast of many an age gone by,And yet methinks unsung in rhyme,Though dear to bards of chivalry;Nor less of old to Church and State,As authors erudite relate.If so, my harp, thou friend to me,Thy chords I'll touch right merrily—Then a fire-side picture of Christmas in the country:—

The doughty host has gather'd roundThose most for wit and mirth renown'd,And soon each neighbouring Squire will beWith all the world in charity—Its cares and troubles all forgetting,Good-humour'd joke alone abetting.'Tis good and cheering to the soulTo see the ancient wassail bowlNo longer lying on its face,Or dusty in its hiding place.It brings to mind a day gone by,Our fathers and their chivalry—It speaks of courtly Knight and Squire,Of Lady's love, and Dame, and Friar,Of times, (perchance not better now,)When care had less of wrinkled brow—When she with hydra-troubled mien,Our greatest enemy, the Spleen,Was seldom, or was never seen.Now pledge they round each other's name,And drink to Squire and drink to Dame,While here, more precious far than gold,Sits womanhood, with modest eye—Glances to her the truth unfold,She shall not pass unheeded by.T'was woman that with health did greet,When Vortigern did Hengist meet—'Twas fair Rowena, Saxon maid,In blue-ey'd majesty array'd,Presented 'neath their witching rollTo British Chief the wassail bowl.She touch'd to him, nor then in vain,He back return'd the health again.Thus 'tis with feelings kind as trueThey drink the tribute ever due,Nor would they less, tho' truth denied it,Their love for woman would decide it.Right merry now the hours they pass,Fleeting thru jocund pleasure's glass,The yule-clog too burns bright and clear,Auspicious of a happy year:While some with joke, and some with taleBut all with sweeter mulled ale,Pass gaily time's swift stream along,With interlude of ancient song—And as each rosy cup they drain,Bounty replenishes again.An happy time! hours like to these,Tho' fleeting, never fail to please.Who reigns, who riots, or who sings,Or who enjoys the smiles of kings.What preacher follows half the town;Who pleads, with or without a gown;Who rules his wife, or who the state;Who little, or who truly great;What matters light the world amuse,Where half the other half abuse;Whether it shall be peace or war,Or we remain just as we are—Is all as one to those we seeAround the cup of jollity.Old age, with joke will still crack on,And story will be dwelt upon—Till Christmas shows his ruddy nose,They will not seek for night's repose,Nor this their jovial meeting close.A FRIEND

In utter prostration, and sacred privacy of soul, I almost think now, and have often felt heretofore, man may make a confessional of the breast of his brother man. Once I had such a friend—and to me he was a priest. He has been so long dead, that it seems to me now, that I have almost forgotten him—and that I remember only that he once lived, and that I once loved him with all my affections. One such friend alone can ever, from the very nature of things, belong to any one human being, however endowed by nature and beloved of heaven. He is felt to stand between us and our upbraiding conscience. In his life lies the strength—the power—the virtue of ours—in his death the better half of our whole being seems to expire. Such communion of spirit, perhaps, can only be in existences rising towards their meridian; as the hills of life cast longer shadows in the westering hours, we grow—I should not say more suspicious, for that may be too strong a word—but more silent, more self-wrapt, more circumspect—less sympathetic even with kindred and congenial natures, who will sometimes, in our almost sullen moods or theirs, seem as if they were kindred and congenial no more—less devoted to Spirituals, that is, to Ideas, so tender, true, beautiful, and sublime, that they seem to be inhabitants of heaven though born of earth, and to float between the two regions, angelical and divine—yet felt to be mortal, human still—the Ideas of passions, and desires, and affections, and "impulses that come to us in solitude," to whom we breathe out our souls in silence, or in almost silent speech, in utterly mute adoration, or in broken hymns of feeling, believing that the holy enthusiasm will go with us through life to the grave, or rather knowing not, or feeling not, that the grave is any thing more for us than a mere word with a somewhat mournful sound, and that life is changeless, cloudless, unfading as the heaven of heavens, that lies to the uplifted fancy in blue immortal calm, round the throne of the eternal Jehovah.—Noctes—Blackwood's Magazine.

ENGLISH LANDSCAPE PAINTING

The English school of landscape painting has come to be of the first rank, and the contemporaries of Turner, Constable, Calcott, Thomson, Williams, Copley Fielding, and others whom we might name even with these masters, have no reason to reproach themselves with any neglect of their merits. The truth with which these artists have delineated the features of British landscape is, according to general admission, unmatched by even the most splendid exertions of foreign schools in the same department.—Quarterly Rev..

PANORAMA OF THE RHINE

Mr. Leigh, who is well known as the publisher of the best English guides all over the continent, has just added to their number a Panorama of the Rhine and the adjacent country, from Cologne to Mayence, with maps of the routes from London to Cologne, and from thence to the sources of the Rhine. The Panorama is designed from nature by F.W. Delkeskamp, and engraved by John Clark. It consists of a beautiful aqua-tint engraving, upwards of seven feet in length, and six inches in width, representing the course of the Rhine, and its picturesque banks, studded with towns and villages; whilst steam-boats, bridges, and islets are distinctly shown in the river. It would be difficult to convey to our readers an idea of the extreme delicacy with which the plate is engraved; and, to speak dramatically, the entire success of the representation. A more interesting or useful companion for the tourist could scarcely be conceived; for the picture is not interrupted by the names of the places, but these are judiciously introduced in the margins of the plate. In short, every town, village, fortress, convent, mansion, mountain, dale, field, and forest, are here represented. By way of Supplement to the Plate, a Steam-boat Companion is appended, describing the principal places on the Rhine, with the population, curiosities, inns, &c. We passed an hour over the engraving very agreeably, coasting along till we actually fancied ourselves in one of the apartments of the Hotel of Darmstadt at Mayence, when missing our high conic bumper of Rudesheim—we found our thanks were due to the artist for the luxury of the illusion. The Panorama folds up in a neat portfolio, and occupies little more room than a quire of letter paper.

EDINBURGH IN SUMMER

A' The lumms smokeless! No ae jack turnin' a piece o' roastin' beef afore ae fire in ony ae kitchen in a' the New Toon! Streets and squares a' grass-grown, sae that they micht be mawn! Shops like bee-hives that hae de'd in wunter! Coaches settin' aff for Stirlin', and Perth, and Glasgow, and no ae passenger either inside or out—only the driver keepin' up his heart wi' flourishin' his whup, and the guard, sittin' in perfect solitude, playin' an eerie spring on his bugle-horn! The shut-up play-house a' covered ower wi' bills that seem to speak o' plays acted in an antediluvian world! Here, perhaps, a leevin' creter, like ane emage, staunin' at the mouth o' a close, or hirplin' alang, like the last relic o' the plague. And oh! but the stane-statue o' the late Lord Melville, staunin' a' by himsell up in the silent air, a hunder-and-fifty feet high, has then a ghastly seeming in the sky, like some giant condemned to perpetual imprisonment on his pedestal, and mournin' ower the desolation of the city that in life he loved so well.—Noctes—Blackwood's Magazine.