полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 530, January 21, 1832

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 19, No. 530, January 21, 1832

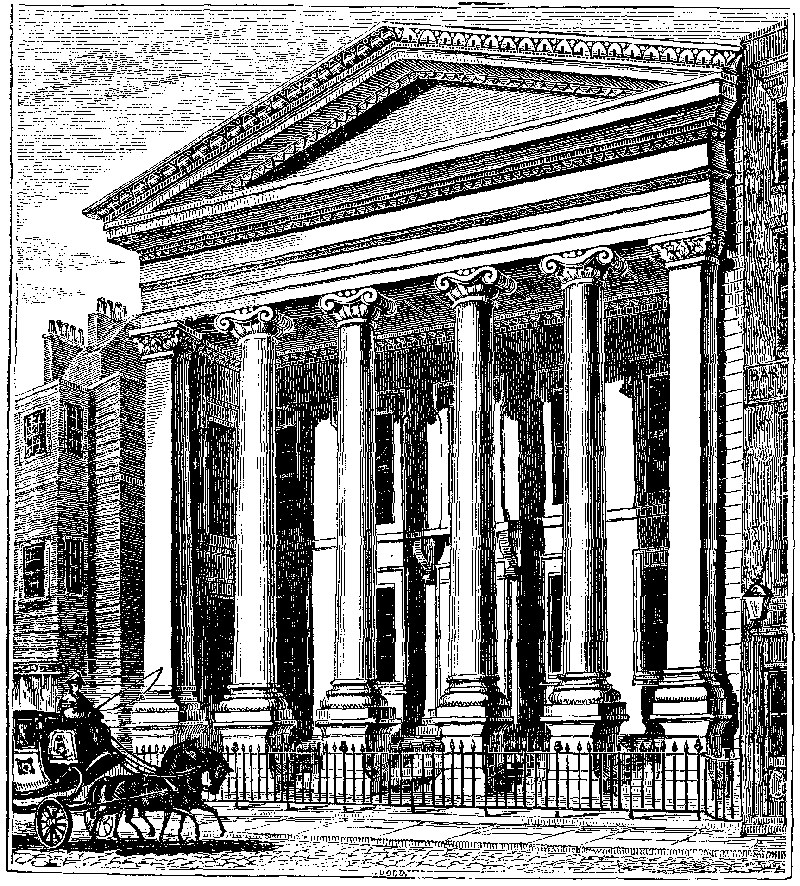

LAW INSTITUTION

This handsome portico is situate on the west side of Chancery Lane. It represents, however, but a portion of the building, which extends thence into Bell Yard, where there is a similar entrance. The whole has been erected by Messrs. Lee and Sons, the builders of the new Post Office and the London University; whose contract for the present work is stated at 9,214l. The portion in our engraving is one of the finest structures of its kind in the metropolis. The bold yet chaste character of the Ionic columns, and the rich foliated moulding which decorates the pediment, as well as the soffit ceiling of the portico, must be greatly admired. We should regret this handsome structure being pent up in so narrow a street as Chancery Lane, did not the appropriateness of its situation promise advantages of greater importance than mere architectural display.

From the Fourth Annual Report, we learn that "the plan of the Law Institution originated with some individuals in the profession, who were desirous of increasing its respectability, and promoting the general convenience and advantage of its members." Rightly enough it appeared to them "singular, that whilst the various public bodies, companies, and commercial and trading classes in the metropolis, and indeed in many of the principal towns in the kingdom, have long possessed places of general resort, for the more convenient transaction of their business; and while numerous institutions for promoting literature and science amongst all ranks and conditions of society, have been long established, and others are daily springing up, the attorneys and solicitors of the superior courts of record at Westminster should still be without an establishment in London, calculated to afford them similar advantages; more particularly when the halls and libraries of the inns of court, the clubs of barristers, special pleaders, and conveyancers, the libraries of the advocates and writers to the signet at Edinburgh, and the association of attorneys in Dublin, furnish a strong presumption of the advantages which would probably result from an establishment of a similar description for attorneys in London.

"For effecting the purposes of the institution, it was considered necessary to raise a fund of 50,000l. in shares of 25l. each, payable by instalments, no one being permitted to take more than twenty shares. The plan having been generally announced to the profession, a large proportion of the shares were immediately subscribed for, so that no doubt remained of the success of the design, and the committee therefore directed inquiries to be made for a site for the intended building, and succeeded in obtaining an eligible one in Chancery Lane, nearly opposite to the Rolls Court, consisting of two houses, formerly occupied by Sir John Silvester (and lately by Messrs. Collins and Wells,) and Messrs. Clarke, Richards and Medcalf, and of the house behind, in Bell Yard, lately in the possession of Mr. Maxwell; thus having the advantage of two frontages, and, from its contiguity to the law offices and inns of court, being peculiarly adapted to the objects of the institution."

"It is the present intention of the committee to provide for the following objects:—viz—A Hall, to be open at all hours of the day; but some particular hour to be fixed as the general time for assembling: to be furnished with desks, or inclosed tables, affording similar accommodations to those in Lloyd's Coffee House; and to be provided with newspapers and other publications calculated for general reference."

"An Ante-room for clerks and others, in which will be kept an account of all public and private parliamentary business, in its various stages, appeals in the House of Lords, the general and daily cause papers, seal papers, &c."

"A Library to contain a complete collection of books in the law, and relating to those branches of literature which may be considered more particularly connected with the profession; votes, reports, acts, journals, and other proceedings of parliament; county and local histories; topographical, genealogical, and other matters of antiquarian research, &c. &c."

"An Office of Registry in which will be kept accounts and printed particulars of property intended for sale, &c."

"A Club Room which may afford members an opportunity of procuring dinners and refreshments, on the plan of the University, Athenaeum, Verulam, and similar clubs."

"A suite of rooms for meetings."

"Fire-proof rooms, in the basement story, to be fitted up with closets, shelves, drawers, and partitions, for the deposit of deeds, &c."

Upon reference to the list of members to Jan. 1831, we find their number to be 607 in town, and 88 in the country, who hold 2000 shares in the Institution. A charter of incorporation has recently been granted to the Society by his Majesty, by the style of "The Society of Attorneys, Solicitors, Proctors, and others, not being Barristers, practising in the Courts of Law and Equity in the United Kingdom," thus giving full effect to the arrangements contemplated by this building in Chancery Lane.

HOPE

(For the Mirror.)He mark'd two sunbeams upward drivenTill they blent in one in the bosom of heaven;And when closed o'er the eye lid of night,His own mind's eye saw it doubly bright,And as upward and upward it floated onHe deemed it a seraph—and anon.Through its light on heaven's floor he made,The shadow bright of his dead love's shade,In her living beauty, and he wrapt her in light,Which dropped from the eye of the Infinite.And as she breathed her heavenward sigh,'Twas halved by that light all radiently,As it lit her up to eternity.Then the future opened its ocult scroll.And his own inward man was refined to soul,And straightway it rose to the realms above,On the wings of thought till it joined his love,And though from that beauteous trance he wokeStill linger'd the thought—and he called it—hope!LOVE'S KERCHIEF

(For the Mirror.)It was a custom in my time to look through a handkerchief at the new year's moon, and as many moons as ye saw (multiplied by the handkerchief,) so many years would ye be before ye were wed.

When sunset and moon-riseChill and burn at once on the earth—When love-tears and love-sighsTickle up boisterous mirth—When fate-stars are shooting,Sparks of love to the maidTo fill her funeral eye with light,And owlets are hootingHer sire's ghost, which she's unlaidWith vexation, down backward in night;Then the lover may spin from that light of her eye,(As through his sigh it glances silkily,)With the wheel of a dead witch's fancy,The thread of his after destiny—All hidden things to prove.Then make a warp and a woof of that thread of sight,And weave it with loom of a fairy sprite,As she works by the lamp of the glow-worm's light,While it lays drunk with the dew-drop of night,And ye'll have the kerchief of love:Then peep through it at the waning moon,And ye shall read your fate—anon.A SKETCH OF SINGAPORE. 1

Near the village of Kampong Glam2 I observed a poor-looking bungalow, surrounded by high walls, exhibiting effects of age and climate. Over the large gateway which opened into the inclosure surrounding this dwelling were watch-towers. On inquiry, I found this was the residence of the Rajah of Johore, who includes Sincapore also in his dominions. The island was purchased of him by the British Government, who now allow him an annual pension. He is considered to have been formerly a leader of pirates; and when we saw a brig he was building, it naturally occurred to our minds whether he was about to resort to his old practices. We proposed visiting this personage; and on arriving at the gateway were met by a peon, who, after delivering our message to the Rajah, requested us to wait a few minutes, until his Highness was ready. We did not wait long, for the Rajah soon appeared, and took his seat, in lieu of a throne, upon the highest step of those which led to his dwelling. His appearance was remarkable: he appeared a man of about forty years of age—teeth perfect, but quite black, from the custom of chewing the betel constantly. His head was large; and his shaven cranium afforded an interesting phrenological treat. He was deformed; not more than five feet in height, of large body, and short, thick, and deformed legs, scarcely able to support the ponderous trunk. His neck was thick and short, and his head habitually stooped; his face bloated, with the lower lip projecting, and large eyes protruding, one of them having a cataractal appearance. He was dressed in a short pair of cotton drawers, a sarong of cotton cloth came across the shoulders in the form of a scarf, and with tarnished, embroidered slippers, and handkerchief around the head (having the upper part exposed) after the Malay fashion, completed the attire of this singular creature.

As much grace and dignity was displayed in our reception as such a figure could show, and chairs were placed by the attendants for our accommodation. He waddled a short distance, and, notwithstanding the exertion was so extraordinary as to cause large drops of perspiration to roll down his face, conferred a great honour upon us by personally accompanying us to see a tank he had just formed for fish, and with a flight of steps, for the convenience of bathing. After viewing this, he returned to his former station, when he re-seated himself, with a dignity of look and manner surpassing all description; and we took our departure, after a brief common-place conversation.

I remarked, that on his approach the natives squatted down, as a mark of respect: a custom similar to which prevails in several of the Polynesian islands.

Mr. G.B.'s MS. Jour., Nov. 15, 1830.

MANNERS & CUSTOMS OF ALL NATIONS

ROYAL AND NOBLE GLUTTONY

(For the Mirror.)The Emperor Claudius had a strong predilection for mushrooms: he was poisoned with them, by Agrippina, his niece and fourth wife; but as the poison only made him sick, he sent for Xenophon, his physician, who, pretending to give him one of the emetics he commonly used after debauches, caused a poisoned feather to be passed into his throat.

Nero used to call mushrooms the relish of the gods, because Claudius, his predecessor, having been, as was supposed, poisoned by them, was, after his death, ranked among the gods.

Domitian one day convoked the senate, to know in what fish-kettle they should cook a monstrous turbot, which had been presented to him. The senators gravely weighed the matter; but as there was no utensil of this kind big enough, it was proposed to cut the fish in pieces. This advice was rejected. After much deliberation, it was resolved that a proper utensil should be made for the purpose; and it was decided, that whenever the emperor went to war a great number of potters should accompany him. The most pleasing part of the story is, that a blind senator seemed in perfect ecstacy at the turbot, by continually praising it, at the same time turning in the very opposite direction.

Julius Caesar sometimes ate at a meal the revenues of several provinces.

Vitellius made four meals a day; and all those he took with his friends never cost less than ten thousand crowns. That which was given to him by his brother was most magnificent: two thousand select dishes were served up: seven thousand fat birds, and every delicacy which the ocean and Mediterranean sea could furnish.

Nero sat at the table from midday till midnight, amidst the most monstrous profusion.

Geta had all sorts of meat served up to him in alphabetical order.

Heliogabalus regaled twelve of his friends in the most incredible manner: he gave to each guest animals of the same species as those he served them to eat; he insisted upon their carrying away all the vases or cups of gold, silver, and precious stones, out of which they had drunk; and it is remarkable, that he supplied each with a new one every time he asked to drink. He placed on the head of each a crown interwoven with green foliage, and gave each a superbly-ornamented and well-yoked car to return home in. He rarely ate fish but when he was near the sea; and when he was at a distance from it, he had them served up to him in sea-water.

Louis VIII. invented a dish called Truffes a la purée d'ortolans. The happy few who tasted this dish, as concocted by the royal hand of Louis himself, described it as the very perfection of the culinary art. The Duc d'Escars was sent for one day by his royal master, for the purpose of assisting in the preparation of a glorious dish of Truffes a la purée d'ortolans; and their joint efforts being more than usually successful, the happy friends sat down to Truffes a la purée d'ortolans for ten, the whole of which they caused to disappear between them, and then each retired to rest, triumphing in the success of their happy toils. In the middle of the night, however, the Duc d'Escars suddenly awoke, and found himself alarmingly indisposed. He rang the bells of his apartment, when his servant came in, and his physicians were sent for; but they were of no avail, for he was dying of a surfeit. In his last moments he caused some of his attendants to go and inquire whether his majesty was not suffering in a similar manner with himself, but they found him sleeping soundly and quietly. In the morning, when the king was informed of the sad catastrophe of his faithful friend and servant, he exclaimed, "Ah, I told him I had the better digestion of the two."

W.G.C.

THE SKETCH BOOK

EVERY MAN IN HIS HUMOUR. A FRAGMENT

(For the Mirror.)During the rage of the last continental war in Europe, occasion—no matter what—called an honest Yorkshire squire to take a journey to Warsaw. Untravelled and unknowing, he provided himself no passport: his business concerned himself alone, and what had foreign nations to do with him? His route lay through the states of neutral and contending powers. He landed in Holland—passed the usual examination; but, insisting that the affairs which brought him there were of a private nature, he was imprisoned—questioned—sifted;—and appearing to be incapable of design, was at length permitted to pursue his journey.

To the officer of the guard who conducted him to the frontiers he made frequent complaints of the loss he should sustain by the delay. He swore it was uncivil, and unfriendly, and ungenerous: five hundred Dutchmen might have travelled through Great Britain without a question,—they never questioned any stranger in Great Britain, nor stopped him, nor imprisoned him, nor guarded him.

Roused from his native phlegm by these reflections on the police of his country, the officer slowly drew the pipe from his mouth, and emitting the smoke, "Mynheer," said he, "when you first set your foot on the land of the Seven United Provinces, you should have declared you came hither on affairs of commerce;" and replacing his pipe, relapsed into immovable taciturnity.

Released from this unsocial companion, he soon arrived at a French post, where the sentinel of the advanced guard requested the honour of his permission to ask for his passports. On his failing to produce any, he was entreated to pardon the liberty he took of conducting him to the commandant—but it was his duty, and he must, however reluctantly, perform it.

Monsieur le Commandant received him with cold and pompous politeness. He made the usual inquiries; and our traveller, determined to avoid the error which had produced such inconvenience, replied that commercial concerns drew him to the continent. "Ma foi," said the commandant, "c'est un negotiant, un bourgeois"—take him away to the citadel, we will examine him to-morrow, at present we must dress for the comedie—"Allons."

"Monsieur," said the sentinel, as he conducted him to the guard-room, "you should not have mentioned commerce to Monsieur le Commandant; no gentleman in France disgraces himself with trade—we despise traffic; you should have informed Monsieur le Commandant, that you entered the dominions of the Grand Monarque to improve in dancing, or in singing, or in dressing: arms are the profession of a man of fashion, and glory and accomplishments his pursuits—Vive le Roi."

He had the honour of passing the night with a French guard, and the next day was dismissed. Proceeding on his journey, he fell in with a detachment of German Chasseurs. They demanded his name, quality, and business. He came he said to dance, and to sing, and to dress. "He is a Frenchman," said the corporal—"A spy!" cries the sergeant. He was directed to mount behind a dragoon, and carried to the camp.

There he was soon discharged; but not without a word of advice. "We Germans," said the officer, "eat, drink, and smoke: these are our favourite employments; and had you informed the dragoons you followed no other business, you would have saved them, me, and yourself, infinite trouble."

He soon approached the Prussian dominions, where his examination was still more strict; and on answering that his only designs were to eat, and to drink, and to smoke—"To eat! and to drink! and to smoke!" exclaimed the officer with astonishment. "Sir, you must he forwarded to Postdam—war is the only business of mankind." The acute and penetrating Frederick soon comprehended the character of our traveller, and gave him a passport under his own hand. "It is an ignorant, an innocent Englishman," says the veteran; "the English are unacquainted with military duties; when they want a general they borrow him of me."

At the barriers of Saxony he was again interrogated. "I am a soldier," said our traveller, "behold the passport of the first warrior of the age."—"You are a pupil of the destroyer of millions," replied the sentinel, "we must send you to Dresden; and, hark'e, sir, conceal your passport, as you would avoid being torn to pieces by those whose husbands, sons, and relations have been wantonly sacrificed at the shrine of Prussian ambition." A second examination at Dresden cleared him of suspicion.

Arrived at the frontiers of Poland, he flattered himself his troubles were at an end; but he reckoned without his host.

"Your business in Poland?" interrogated the officer.

"I really don't know, sir."

"Not know your own business, sir!" resumed the officer; "I must conduct you to the Starost."

"For the love of God," said the wearied traveller, "take pity on me. I have been imprisoned in Holland for being desirous to keep my own affairs to myself;—I have been confined all night in a French guard-house, for declaring myself a merchant;—I have been compelled to ride seven miles behind a German dragoon, for professing myself a man of pleasure;—I have been carried fifty miles a prisoner in Prussia, for acknowledging my attachment to ease and good living;—I have been threatened with assassination in Saxony, for avowing myself a warrior. If you will have the goodness to let me know how I may render such an account of myself as not to give offence, I shall ever consider you as my friend and protector."

M—A—NS.

RETROSPECTIVE GLEANINGS

SPEECH OF KING HENRY THE FIRST

(To the Editor.)The following speech of Henry the First will, no doubt, be thought by some of your numerous readers curious enough to deserve a corner in your valuable Mirror. It is the first that ever was delivered from the throne;—is preserved to us by only one historian (Mathew Paris), and scarcely taken notice of by any other. Henry the First, the Conqueror's youngest son, had dispossessed his eldest brother, Robert, of his right of succession to the crown of England. The latter afterwards coming over to England, upon a friendly visit to him, and Henry, being suspicious that this circumstance might turn to his disadvantage, called together the great men of the realm, and spoke to them as follows:—

"My friends and faithful subjects, both natives and foreigners,—You all know very well that my brother Robert was both called by God, and elected King of Jerusalem, which he now might have happily governed; and how shamefully he refused that rule, for which he justly deserves God's anger and reproof. You know also, in many other instances, his pride and brutality: because he is a man that delights in war and bloodshed, he is impatient of peace. I know that he thinks you a parcel of contemptible fellows: he calls you a set of gluttons and drunkards, whom he hopes to tread under his feet. I, truly a king, meek, humble, and peaceable, will preserve and cherish you in your ancient liberties, which I have formerly sworn to perform; will hearken to your wise councils with patience; and will govern you justly, after the example of the best of princes. If you desire it, I will strengthen this promise with a written character; and all those laws which the Holy King Edward, by the inspiration of God, so wisely enacted, I will again swear to keep inviolably. If you, my brethren, will stand by me faithfully, we shall easily repulse the strongest efforts the cruelest enemy can make against me and these kingdoms. If I am only supported by the valour of the English nation, all the weak threats of the Normans will no longer seem formidable to me."

The historian adds, that this harrangue of Henry to his nobles had the desired effect, though he afterwards broke all his promises to them. Duke Robert went back much disgusted; when his brother soon after followed, gained a victory over him, took him prisoner, put out his eyes, and condemned him to perpetual imprisonment.

G.K.

REMEDY FOR ALDERMEN SLEEPING IN CHURCH

"Sleep no more."—Macbeth.Bishop Andrews was applied to for advice by a corpulent alderman of Cambridge, who had been often reproved for sleeping at church, and whose conscience troubled him on this account. Andrews told him it was an ill habit of body, and not of mind, and advised him to eat little at dinner. The alderman tried this expedient, but found it ineffectual. He applied again with great concern to the bishop, who advised him to make a hearty meal, as usual, but to take his full sleep before he went to church. The advice was followed, and the alderman came to St. Mary's Church, where the preacher was prepared with a sermon against sleeping at church, which was thrown away, for the good alderman looked at the preacher during the whole sermon time, and spoiled the design.

P.T.W.

THE NATURALIST

THE BARN OWL

(Concluded from page 28.)When I found that this first settlement on the gateway had succeeded so well, I set about forming other establishments. This year I have had four broods, and I trust that next season I can calculate on having nine. This will be a pretty increase, and it will help to supply the place of those which in this neighbourhood are still unfortunately doomed to death, by the hand of cruelty or superstition. We can now always have a peep at the owls, in their habitation on the old ruined gateway, whenever we choose. Confident of protection, these pretty birds betray no fear when the stranger mounts up to their place of abode. I would here venture a surmise, that the barn owl sleeps standing. Whenever we go to look at it, we invariably see it upon the perch bolt upright, and often with its eyes closed, apparently fast asleep. Buffon and Bewick err (no doubt, unintentionally) when they say that the barn owl snores during its repose. What they took for snoring was the cry of the young birds for food. I had fully satisfied myself on this score some years ago. However, in December, 1823, I was much astonished to hear this same snoring kind of noise, which had been so common in the month of July. On ascending the ruin, I found a brood of young owls in the apartment.

Upon this ruin is placed a perch, about a foot from the hole at which the owls enter. Sometimes, at midday, when the weather is gloomy, you may see an owl upon it, apparently enjoying the refreshing diurnal breeze. This year (1831) a pair of barn owls hatched their young, on the 7th of September, in a sycamore tree near the old ruined gateway.