полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 531, January 28, 1832

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 19, No. 531, January 28, 1832

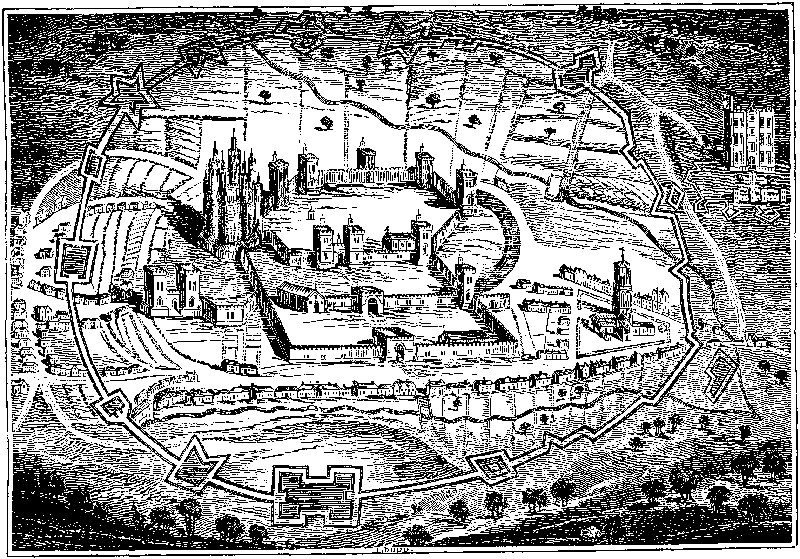

PONTEFRACT CASTLE, 1648

PONTEFRACT CASTLE

Pontrefact, a place of considerable note in English history, is situated about two miles south-west from Ferrybridge, nine miles nearly east from Wakefield, and fifteen miles north-west from Doncaster, in Yorkshire. The origin of the town is unknown; and the etymology of its name has been a matter of dispute, in which figures a monkish legend ascribing the name of Ponsfractus, or Pontefract, to the breaking of a bridge, and the fall of many persons into the river Aire, who were miraculously saved by St. William, Archbishop of York. The river Ouse and the city of York, however, put in a stronger claim as the scene of this miracle, and unfortunately for Pontefract, the town is so named in charters of fifty-three years' date before the miracle is pretended to have been performed. Still the etymology is referable to the breaking down of "some bridge," (pons, bridge; fractus, broken,) but this unravelment is not antiquarian. Camden says, that in the Saxon times, the name of this town was Kirkby, which was changed by the Normans to Pontefract, because of a broken bridge that was there. But as there is no river within two miles of the place, this bridge appears to have been built over the Wash, which lies about a quarter of a mile to the east of the Castle. Other researches prove Pontefract to have been a secondary and subordinate Roman station.

The history of the Castle is, of course, involved in that of the manor. The town is stated to have been a burgh in the time of Edward the Confessor; but how long it had enjoyed this privilege is uncertain.1 After the Conquest, this manor, with 150 others, or the greatest part of so many in Yorkshire, besides ten in Nottinghamshire, and four in Lincolnshire, were given by William to Hildebert, or Ilbert de Lacy, one of his Norman followers, who built the Castle. The work occupied twelve years, and it was finished in 1080. The labour and expense of its erection was so great, that no person unless in the possession of a princely fortune, could have completed a work of such magnitude. Hildebert was succeeded by his son Robert, commonly called Robert de Pontefract, from his being born at that town. Robert enjoyed his vast possessions in peace during the reign of William Rufus; but after the accession of Henry I. he with more ambition than prudence, joined with Robert, Duke of Normandy, the King's brother, who claimed the crown of England. In consequence of this transaction, Robert de Lacy was banished the realm, and the castle and honour of Pontefract were given by the King to Henry Traverse, and afterwards to Henry De-laval.2 Robert de Lacy was, however, restored after a few years exile, and the property continued in the Lacy family till the year 1193, when another Robert de Lacy dying without issue, the estate and honour of Pontefract devolved on his uterine sister Aubrey de Lisours, who carried these estates of the Lacys by marriage to Richard Fitz-Eustace, constable of Chester. Thence they descended to John Fitz-Eustace, who accompanied Richard I. in his crusade, and is said to have died at Tyre in Palestine. Roger, his eldest son, also in the crusade, succeeded to his honour and estates. He was present with Richard at the memorable siege of Acre. On his return to England he was the first of his family that took the name of Lacy, in which Pontefract Castle continued till 1310, when Henry de Lacy, through default of male issue, left his possessions to his daughter and heiress, Alice, who was married to Thomas, Earl of Lancaster; and, in case of a failure of issue from that marriage, he entailed them on the King and his heirs.

The Earl of Lancaster, it will be remembered, became embroiled with Edward II. and his minion Gaveston, who partly through the interference of Lancaster, was beheaded at Warwick after a siege in Scarborough Custle. The King swore vengeance for the death of his favourite, which led this weak sovereign into a long series of dissentions with the barons, at the head of whom, was the Earl of Lancaster. Both parties now flew to arms, but Lancaster soon found himself ill supported by his compeers, and marching northward for reinforcements from the celebrated Bruce, King of Scotland, the King in the meantime, sent the Earl of Surrey and Kent to besiege the castle of Pontefract, which surrendered at the first summons. Lancaster was next closely pursued by the king with great superiority of numbers. "The earl, endeavouring to rally his troops, was taken prisoner, with ninety-five barons and knights, and carried to the castle of Pontefract, where he was imprisoned in a tower which Leland says he had newly made towards the abbey," This tower was square: its wall of great strength, being 10-1/2 feet thick; nor was there any other entrance into the interior than by a hole or trap-door in the floor of the turret: so that the prisoner must have been let down into this abode of darkness, from whence there could be no possible mode of escape; the room was twenty-five feet square. A few days after, the King being at Pontefract ordered him to be arraigned in the hall of the castle, before a small number of peers, among whom were the Spencers, his mortal enemies. The earl was condemned to be hanged, drawn, and quartered; but the punishment was changed to decapitation. After sentence was passed, he said, "Shall I die without answer?" He was not, however, permitted to speak; but a certain Gascoign took him away, and having put an old hood over his head, set him on a lean mare without a bridle. Being attended by a Dominican friar as his confessor, he was carried out of the town amidst the insults of the people; and there beheaded. Thus fell Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, the first Prince of the Blood, being uncle to Edward II. who condemned him to death. Several of his adherents were hanged at Pontefract.

The next royal blood that stained Pontefract castle was that of King Richard II. who was here murdered or starved to death; though there is a tradition that it was merely given out that Richard had starved himself to death, and that he escaped from Pontefract to Mull, whence he shortly proceeded to the mainland of Scotland, where, for nineteen years, he was entertained in an honourable but secret captivity.3 The matter remains in tragic darkness.4 In the succeeding reign of Henry IV. Richard Scroope, archbishop of York, being taken prisoner, was in Pontefract castle, condemned to death. Next in the calendar of atrocities committed within these drear walls, were the murders of Anthony Woodville, Earl Rivers; Richard, Lord Grey; Sir Thomas Vaughan; and Sir Richard Hawse, in 1483; by Richard III., whom Shakspeare makes to whine forth:

O Pomfret, Pomfret! O thou bloody prison!Fatal and ominous to noble peers!Within the guilty closure of thy walls,Richard II. here was hack'd to death;And for more slander to thy dismal seat,We give to thee our guiltless blood to drink.We may now pass over matters of minor importance in the history of Pontefract to the time of Charles I. In the King's contest with his Parliament, this was the last fortress that held out for the unfortunate monarch. At Christmas 1644, Sir Thomas Fairfax laid siege to the castle, and on Jan. 19, following, after an incessant cannonade of three days, a breach was made: the brave garrison would not surrender; the besiegers mined, but the besieged counter-mined, and the work of slaughter went on till the garrison were greatly reduced. At length the Parliamentarians were attacked and repulsed by a reinforcement of Royalists from Oxford, and thus ended the first siege of Pontefract. In March, 1645, the enemy again took possession of the town, and after three months cannonade, the garrison being reduced almost to a state of famine, surrendered the castle by an honourable capitulation on June 20. Sir Thomas Fairfax was appointed governor, and he thinking the royal party to be subdued, appointed a colonel as his substitute, with a garrison of 100 men. The royalists next by stratagem recovered Pontefract, of which Sir John Digby was appointed governor.

The third and final siege of this fine castle commenced in October, 1648. General Rainsborough was appointed to the command of the army, but he being previously intercepted at Doncaster, Oliver Cromwell undertook to conduct the siege. After having remained a month before the fortress, without making any impression on its massy walls, Cromwell joined the grand army under Fairfax, and General Lambert being appointed commander in chief of the forces before the castle, arrived at Pontefract on the 4th of December.

The ENGRAVING represents the castle precisely at this period. It is copied from a large print taken from a drawing found in the possession of a descendant of the Fairfax family of Denton; in one angle is the following memorandum: "Governor Morris commanded in the Castle. General Lambert commanded the Siege, being appointed thereto on the death of General Rainsborough, who was intercepted and killed at Doncaster, by a party from the Castle, as he was going to take command."

General Lambert raised new works, and vigorously pushed the siege; but the besieged held out. On January 30, 1649, the King was beheaded; and the news no sooner reached Pontefract, than the royalist garrison proclaimed his son Charles II. and made a vigorous and destructive sally against their enemies. The Parliamentarians, however, prevailed, and on March 25, 1649, the garrison being reduced from 500 or 600 to 100 men, surrendered by capitulation. Six of the principal Royalists were excepted from mercy: two escaped, but were retaken and executed at York; the third was killed in a sortie; and the three others concealing themselves among the ruins of the castle, escaped after the surrender; and two of the last lived to see the Restoration.

This third siege was the most destructive to the castle: the tremendous artillery had shattered its massive walls; and its demolition was completed by order of Parliament. Within two months after its reduction, the buildings were unroofed, and all the materials sold. Thus was this princely fortress reduced to a heap of ruins.

The Castle of Pontefract was built on an elevated rock, commanding extensive and picturesque views. The north-west prospect takes in the beautiful vale along which flows the Aire, skirted by woods and plantations. It is bounded only by the hills of Craven. The north and east prospect is more extensive, but the scenery is not equally striking and impressive. The towers of York Minster are distinctly seen, and the prospect is only bounded by the limits of vision. To the east—while the eye follows the course of the Aire towards the Humber, the fertility of the country, the spires of churches, and two considerable hills, Brayton Barf, and Hambleton Haugh, which rise in the midst of a plain, and one of which is covered with wood, increase the beauty of the scene. The south-east view includes part of the counties of Lincoln and Nottingham. To the south and south-west, the towering hills of Derbyshire, stretching towards Lancashire, form the horizon, while the foreground is a picturesque country variegated with handsome residences.

The Castle, by its situation, as well as by its structure, was rendered almost impregnable. It was not commanded by any contiguous hills, and it could only be taken by blockade.

By referring to the Engraving, the reader will better understand this defence. The outworks are there distinctly shown with the respective posts and guards: indeed, these lines exhibit a fine specimen of fortification. The quadrangular enclosure on the crest of the hill, in the lower part of the Engraving, represents Lamberts' Fort Royal. To the right is the approach to the castle by the south gate to the barbican, crossed by a wall, with the middle gate, with the east gate at the extremity of the line. We next approach, the ballium, or castle yard through the Porter's Lodge of two towers with a portcullis. The wall of the castle-yard, it will be seen, has a parapet, and is flanked with towers, and the chapel to the right of the Lodge. East and West of the yard is seen the semi-circular moat or ditch; and on an eminence near the western extremity of the ballium, stands the keep or round tower, the walls of which are said to have been twenty-one feet thick. The state rooms are on the second story. The dungeons of the towers are terrific even in description: one was about 15 feet deep, and scarcely six feet square, without any admission of light. The whole area occupied by the Pontrefact fortress seems to have been about 7 acres, now converted into garden ground.

The church seen within the work is that of All Saints, or Allhallows, a Gothic structure, probably of the time of Henry III., and almost destroyed in the sieges of the castle.

Pontefract must be numbered in our recollections of childhood; since here were grown whole fields of liquorice root, from the extract of which are made. Pontefract Cakes, impressed with the arms—three lions passant gardant, surmounted with a helmet, full-forward, open faced, and garde-visure. We have likewise seen them impressed with the celebrated fortress, and the motto "Post mortem patris pro filio,"—after the death of the father—for the son—denoting the loyalty of the Pontefract Royalists in proclaiming Charles II. at the death of his father.

"LACONICS," GUESSES AT TRUTH, &c

(For the Mirror.)It is the interest of an indolent man to be honest: for it requires considerable trouble and finesse, to deceive others successfully.

Money was a wise contrivance to place fools somewhat on a level with men of sense.

It will be observed, that people have generally the identical faults and vices they accuse others of; we may instance cowardice.

Wherever a proposition is self-evident, it is but weakening its strength to bring forward arguments in its support.

It is a melancholy reflection that a glass of wine will do more towards raising the spirits, than the finest composition ever penned.

It is a great mistake in physiognomists to take outward signs as evidences of feeling: the seat of real sensation is within.

Wherever art has travelled out of her proper sphere to ape nature, she has proved herself but a miserable mimic, even in her most approved efforts.

We must not allow ourselves to dwell too seriously on life; for otherwise we shall be tempted to forego all our plans, to indulge in no future wishes, and, in short, to live on in torpid apathy.

Books are at last the best companions: they instruct us in silence without any display of superiority, and they attend the pace of each man's capacity, without reproaching him for his want of comprehension.

A disgust of life frequently proceeds from sheer vanity, or a wish to be supposed incapable of deriving gratification from the ordinary routine of happiness.

It sometimes happens that with men as well as animals, that evidences of spirit are only the effect of excited fear.

(To be continued.)

THE LAW INSTITUTION. 5

(At the time of our last publication we were not aware that any architectural details of the building in Chancery-lane had appeared. We now find that the Legal Observer contained such description in March last, "collected," says the editor, "with some pains and trouble." A correspondent dropped the Observer leaf into our letter-box in the course of last week; but, unfortunately, the communication did not reach us in time for insertion with our Engraving. Good news, we know, usually comes upon crutches, but we hope our thanks will reach this correspondent at a better pace.)

The style of architecture of the principal front in Chancery-lane is purely Grecian. The details and proportions appear to have been founded upon the best examples of the Ionic order in Athens and Asia Minor,6 but they are not servilely copied from any of them.

Mr. Vulliamy, the architect for the Institution, has thrown into this front the true spirit of the originals; and the effect which the harmonious proportions of the building produce on the spectator, when viewing it from Chancery-lane, must have been the result of much observation and experience in ancient and classic models.

This front, extending nearly sixty feet in width, is of Portland stone. It consists of four columns and two antae, of the Grecian Ionic order, supporting an entablature and pediment, and forming together one grand portico. To give the requisite elevation, the columns and antae are raised upon pedestals; these, as well as the basement story and podium of the inner wall of the portico, are of Aberdeen granite; the columns and the rest of the front are formed of large blocks of Portland stone. In the front wall, within the portico, there are two ranges of windows above the basement.

The front in Bell-yard extends nearly eighty feet, and will be finished with Roman cement, in imitation of stone. It will have a portico of two columns, and two antae of Portland stone, of the height of the ground story, which is very lofty, and the width of the entire compartment of the front. From the interior requiring to be divided into several rooms, this front must have many windows. The elevation is formed more upon the models of modern domestic architecture than of ancient public buildings, and resembles, in its general appearance, one of the palazzi in the Strada Balbi at Genoa, in the Corso at Rome, or in the Toledo at Naples. In its details, however, the extravagancies of the middle ages, and the often elegant frivolities of the cinque cento period, have been avoided, and the breadth and simplicity of Greek models have still been followed.

The ground plan of the building, by its general arrangement, divides itself into three parts, which may be distinguished under the heads of the Library, the Hall, and the Club Room. The first of these (that towards Chancery-lane) consists, on the ground floor, of a first and second vestibule, and staircase to the Library, the Secretary's Room, and Registry Office; and above these on the first floor, the Library, occupying the height of two stories.

The Library is a large and lofty room, fifty-five feet by thirty-one and a half, and twenty-three and a half high, divided by a screen of columns and pilasters of scagliola, into two unequal parts, the first forming a sort of ante-library to the other; both are surrounded by bookcases of oak, and a gallery runs round the whole, above which is another range of bookcases.

The principal light is obtained from a large lantern-light in the ceiling; but there is a range of windows (double sashed, and glazed with plate glass) towards Chancery-lane, which also admit light into the lower part.

All the floors in the building are made fire-proof, generally by being arched with brick; but that of the Library is rendered secure from fire by the ceilings of the vestibules underneath being formed of real stone, supported on iron girders and bearers, and divided into panels and compartments after the manner of the roofs of the peristyles of the ancient temples.

There are three entrances from Chancery-lane: that in the centre is exclusively for members, and leads to all parts of the building; that on the right for persons going to the Registry Office; and also for persons having to speak to members; that on the left leads down to the Office for the deposit of deeds, and to the strong rooms.

The second division consists of the Hall and its appurtenances. It is above thirty feet high, and fifty-seven feet and a half long; and on each side it has wings or recesses, behind insulated columns of scagliola, in imitation of Egyptian granite. Within these, and at the back of the columns, are galleries; the staircases to which are concealed in the angles. There are three fireplaces in the Hall; one in the centre, opposite the principal entrance, and one in the centre of each of the recesses. The Hall is lighted by a lantern-light forty feet long and twenty-four feet wide.

The third division is next Bell-yard: it is subdivided into two parts. In the first of these are three entrances from Bell-yard. That in the centre is exclusively for the members; that to the left leads to the staircase to the Secretary's apartments; and the other, to the right of the centre, is for strangers to enter who have business to transact in any of the rooms appropriated to public business. On the ground floor of this part of the third division is a large Committee Room, and an ante or waiting room adjoining, and the great staircase to the rooms above. On the first floor are the rooms for meetings on matters of business connected with the law; and above these are the Secretary's apartments.

The second part of the third division contains, on the ground floor, the Club Room, which occupies all the ground floor: it will be divided by columns and pilasters of scagliola, and decorated with a paneled ceiling and appropriate ornaments. Its dimensions are fifty feet by twenty-seven, and eighteen feet high. On the first floor are rooms of different dimensions for dinner parties; and over these, rooms for the resident officers. In the basement story of this part of the building are the Kitchen and other domestic offices for the use of the Club.

The office for the deposit of deeds is in the basement story, next to Chancery-lane.

In the remaining parts of the basement story of the building are fifty-two strong rooms, with iron doors, for the deposit of deeds, which are well ventilated and fire-proof; their average size is six feet and a half by seven feet and a half, but some are larger, and others rather less, than these dimensions. The whole are secured by one double iron door, with a very strong lock and master-key.

SPIRIT OF DISCOVERY

VAPOUR-BATHS

Among the remedies for cholera, or perhaps we should rather say attempted remedies, the vapour-bath is conspicuous over all the other means of cure, external and internal: stimulants, frictions, rubefacients, blisters, have that for their indirect object which the vapour-bath accomplishes directly, namely, to produce heat on the surface of the body, and thus restore that correspondence between the temperature of the interior and exterior parts, which in the disease is so strangely disturbed. There are two difficulties in the application of the vapour-bath, which are not easily overcome. When applied to the patient in the ordinary way, from the nature of the heat, the upper surface of the body is scorched, while the back is almost cold. Now in cholera, the application of heat to the back is of essential importance. In the whole of the machines for applying the bath, the patient is exposed to more or less tossing about; which, from the extreme prostration of strength in cholera patients, is always injurious; and as the patient must, when taken from the bath, be replaced on a comparatively cold bed, the sudden change will often do more ill than the bath will do good. To these must be added, in a disease which chiefly affects the poor, another item, forming an important drawback on the utility of the ordinary vapour-bath,—the application of it is attended with no inconsiderable expense. A machine which should obviate these objections, was a desideratum; and we think such a one has been invented by Mr. Burnet, of Golden Square. It is so simple as to be easily described without a diagram, and so well adapted to the end, and so easy and cheap in application, that we think we shall be rendering an acceptable service to our readers in describing it. The best way to effect this is to show the steps of its application.

We suppose the patient lying on his back in bed. The two sides of a framework, about 6-1/2 by 2-1/2 feet, are placed one on each side of him; five or six broad canvass straps, which are meant to support his body, are placed beneath him by a couple of attendants; two transverse pieces of wood are then introduced at the foot and head, to extend the framework; and the cross straps, by means of eyelet-holes, are attached to the sides, by a row of common brass pins. This is the work of about a minute. One attendant then raises the frame at the head, while the other introduces a couple of feet about nine inches long into the frame; and this done, the foot is raised in a similar way, and similarly supported; a board is then fitted to the foot, through a hole in the centre of which the chimney of the heating apparatus passes; the blankets are closely tucked round the patient and the frame; the lamp is applied, and the process of bathing commences. In this way, it will be seen that the patient is suspended in the heated air, which is moreover applied to the back in the first instance; there is no fatigue incurred; and when perspiration has been generated and carried on as long as is deemed expedient, he is let down again, without difficulty or danger, into his heated bed, and surrounded with the warm blankets employed in the bath itself. The room in which we saw the experiment performed, was at a temperature of 43° Fahrenheit; the clothes of the bed were of the same temperature: the lamp is conical, and has no tube; the wick is merely inserted in it; the charge is two ounces of spirits of wine. In ten minutes after the lamp had been applied, the thermometer at the foot of the frame on which the patient is made to recline, was 136°; at the head, 116°; on the blanket, which covered the bed, 96°. Were the vapour applied above the patient instead of under him, the difference between the heat at the breast and back would be at least 40°. The temperature once raised, may be kept up at a very small expense; so that the whole price of the bath, continued for half an hour or three quarters of an hour, will not exceed eightpence or ninepence. There is a very simple expedient, by which, when the temperature of the chamber formed by the frame of the bath is once raised sufficiently high, steam, either simple or medicated, may be introduced, and the lamp apparatus may be applied either at the foot, the head, or the side, as is most convenient. The grand recommendation, however, of the bath, is the applicability of the vapour to the entire surface of the body; the simplicity and ease of the application, both to the assistants and the patient; the exclusion of the possibility of cold; and its cheapness. In all these points of view, we look on it as a valuable invention.