полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 19, No. 536, March 3, 1832

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 19, No. 536, March 3, 1832

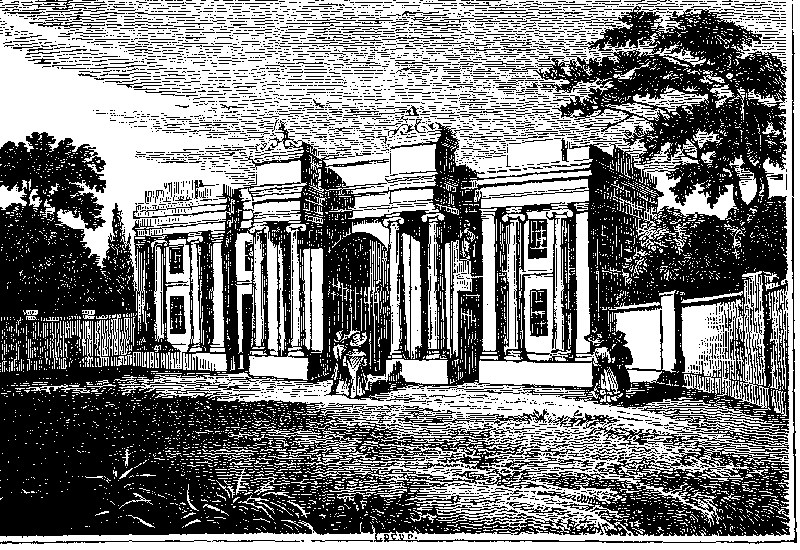

ENTRANCE TO THE BOTANIC GARDEN, MANCHESTER.

Manchester is distinguished among the large towns of the kingdom for its majority of enlightened individuals. "The whole population," it has been pertinently observed by a native, "seems to be imbued with a general thirst for knowledge and improvement." Even amidst the hum of its hundreds of thousand spindles, and its busy haunts of industry, the people have learned to cultivate the pleasures of natural and experimental science, and the delights of literature. The Philosophical Society of Manchester is universally known by its excellent published Memoirs: it has its Royal Institution; its Philological Society, and public libraries; so that incentives to this improvement have grown with its growth. Among these is the Botanical and Horticultural Society, formed in the autumn of 1827, whose primary object was "a Garden for Manchester and its neighbourhood." Previously to its establishment, Manchester had a Floral Society, with six hundred subscribers, which was a gratifying evidence of public taste, as well as encouragement for the Garden design.

We find the promised advantages of the plan thus strikingly illustrated in an Address of the preceding date, "The study of Botany has not been pursued in any part of the country with greater assiduity and success than in the neighbourhood of Manchester. Far from being confined to the higher orders of society, it has found its most disinterested admirers in the lowest walks of life. Though to the skill and perseverance of the cottager we are confessedly indebted for the improved cultivation of many plants and fruits, an extensive acquaintance with the choicest productions of nature, and a philosophical investigation of their properties, are very frequently to be met with in the Lancashire Mechanic. But whilst some knowledge of the principles of Horticulture is almost universal; and the inferior objects of attention are readily procured, it is obvious that the difficulty and expense which attend the possession of plants of rare, and more particularly of foreign growth, form a natural and insurmountable obstruction to the researches of many lovers of the science...." "Whatever regard is due to the rational gratifications of which the most laborious life is not incapable, there is a moral influence attendant on horticultural pursuits, which may be supposed to render every friend of humanity desirous to promote them. The most indifferent observer cannot fail to remark that the cottager who devotes his hours of leisure to the improvement of his garden, is rarely subject to the extreme privations of poverty, and commonly enjoys a character superior to the circumstances of his condition. His taste is a motive to employment, and employment secures him from the temptations to extravagance and the natural consequences of dissipated habits."1 Further, we learn, one great object of the society is to educate a certain number of young men as gardeners. As "an inviting scene of public recreation," it is observed, "those who are little interested in the cultivation of Botany, and who may regard the employments of Horticulture with disdain, may still be induced to frequent the Botanical garden, for the beauty of the objects, the pleasures of the society, and the animating gaiety of the scene."

The Manchester Garden, we should think, must, by this time, have an Eden-like appearance. The Committee began fortunately. Mr. Loudon, in one of his valuable Gardening Tours,2 refers to "a few traits of liberality in the parties connected with it; the noble result, as we think, of the influence of commercial prosperity in liberalizing the mind. Mr. Trafford, the owner of the ground, offered it for whatever price the Committee chose to give for it. The Committee took it at its value to a common farmer, and obtained a lease of the 16 acres (10 Lancashire) for 99 years, renewable for ever at 120l a year." He describes the donations of trees, plants, and books, by surrounding gentlemen, as very liberal. Mr. Loudon does not altogether approve of the plan, and certainly by no means of the manner in which the Garden has been planted, yet he has no doubt it will contribute materially to the spread of improved varieties of culinary vegetables and fruits, and to the education of a superior description of gardeners. He commends the hothouses, which have been executed at Birmingham; especially "the manner in which Mr. Jones has heated the houses by hot water; though a number of the garden committee were at first very much against this mode of heating. Mr. Mowbray (who planned the Garden) informed us that last winter the man could make up the fires for the night at five o'clock, without needing to look at them again till the following morning at eight or nine. The houses were always kept as hot as could be wished, and might have been kept at 100° if thought necessary. A young gardener, who had been accustomed to sit up half the night during winter, to keep up the fires to the smoke flues (elsewhere) was overcome with delight when he came here, and found how easy the task of foreman of the houses was likely to prove to him, as far as concerned the fires and nightwork."

As a means of social improvement, (a feature of public interest, we hope, always to be identified with The Mirror,) we need scarcely add our commendation of the design of the Botanic Garden at Manchester, and similar establishments in other large towns of Britain. What can be a more delightful relaxation to a Lancashire Mechanic than an hour or two in a Garden: what an escape from the pestiferous politics of the times. At Birmingham too, there is a Public Garden, similar to that at Manchester, where we hope the Artisan may enjoy a sight at least of nature's gladdening beauties.

In the suburbs of our great metropolis, matters are not so well managed; though Mr. Loudon, we think, proposes to unite a Botanic with the Zoological Gardens. Folks in London must study botany on their window-sills. The wealthy do not encourage it. Their love of the country is confined to the forced luxuries of kitchen-gardens, conveyed to them in wicker-baskets; and a few hundred exotics hired from a florist, to furnish a mimic conservatory for an evening rout. They shun her gardens and fields; but, as Allan Cunningham pleasantly remarks in his Life of Bonington: "Her loveliness and varieties are not to be learned elsewhere than in her lap. He will know little of birds who studies them stuffed in the museum, and less of the rose and the lily who never saw anything but artificial nose-gays."3

TO A SNOWDROP

A Translation(For the Mirror.)First and fairest of flowery visiter—through the dark winter I have dreamed of thy paleness and thy purity—youngest sister of the lily—likelier, thou art to be loved for thine own sake. Can so delicate a thing spring from an Earthly bed? or art thou, indeed, fallen from the heavens as a Snowdrop? Thus I pluck thee from thy clayey abode, in which, like some of us mortals, thou wouldst find an early grave. I place thee in my bosom, (oh! that it were half so pure as thou), and there shalt thou die. Thou comest like a pure spirit, rising from thy earthly home unsullied and unknown. No longer a child of the dust, thou steppest forth almost too delicately attired at such a season as this. Ye winds of heaven: "breathe on it gently." Ye showers descend on my Snowdrop with the tenderness of dew. Little flower, I love thy look of unpretending innocence: thou art the child of simplicity. Thou art a flower, even though colourless. Wert thou never gay as others? Where are the hues thou once didst wear? Hast thou lent them to the rainbow, or to gay and gaudy flowers, or why so pale? Dost thou fear the winter's wind? Canst thou survive the snow-storm? Tell me: dost thou sleep by starlight, or revel with midnight fairies? My Snowdrop, I pity thee, for thou art a lonely flower. Why camest thou out so early, and wouldst not tarry for thy more cautious spring-time companions? Yet thou knowest not fear, "fair maiden of February." Thou art bold to come out on such a morning, and friendless too. It must be true as they tell me, that thou wert once an icicle, and the breath of some fairy's lips warmed thee into a flower. Indeed thou lookest a frail and fairy thing, and thou wilt not sojourn with us long; therefore it is I make much of thee. Too soon, ah! too soon, will thy graceful form droop and die; yet shall the memory of my Snowdrop be sweet, while memory lasts. I know not that I shall live to see thy drooping head another year. A thousand flowers with a thousand hues will follow after thee, but I will not, I will not forget thee my Snowdrop.

MAJOR CONVOLVULUSOUR LADY'S CHAPEL, SOUTHWARK

It may not plainly appear to some readers that our Engraving of this fine vestige of ancient art, is from a View taken in the year 1818. The Bishop's Chapel, which is there shown, was demolished about twelve months since, at whose bidding we know not; perhaps of the same party who now contend for the destruction of the Lady Chapel.

By the way we referred to the Altar Screen, of which we now find the following memorandum in a History of St. Saviour's Church, published in 1795:4

"Anno 1618. 15 Jac. I. "The screen at the entrance to the chapel of the Virgin Mary was this year set up."

In the same work occur the particulars of the repairs of the Lady Chapel in 1624:

"Anno 1624. 21 Jac. I. "The chapel of the Virgin Mary was restored to the parishioners, being let out to bakers for above sixty years before, and 200l. laid out in the repair. Of which we preserve the following extract from Stowe:

"But passing all these, some what now of that part of this church above the chancell, that in former times was called Our Ladies Chappell.

"It is now called the New Chappell; and indeed, though very old, it now may be called a new one, because newly redeemed from such use and imployment, as in respect of that it was built to, divine and religious duties, may very well be branded, with the style of wretched, base, and unworthy, for that, that before this abuse, was (and is now) a faire and beautifull chappell, by those that were then the corporation (which is a body consisting of thirty vestry-men, six of those thirty, churchwardens) was leased and let out, and the house of God made a bake-house.

"Two very faire doores, that from the two side iles of the chancell of this church, and two that thorow the head of the chancell (as at this day they doe againe) went into it, were lath't, daub'd, and dam'd up: the faire pillars were ordinary posts against which they piled billets and bavens: in this place they had their ovens, in that a bolting place, in that their kneading trough, in another (I have heard) a hogs-trough; for the words that were given mee were these, this place have I knowne a hog-stie, in another a store house, to store up their hoorded meal; and in all of it something of this sordid kind and condition. It was first let by the corporation afore named, to one Wyat, after him, to one Peacocke, after him, to one Cleybrooke, and last, to one Wilson, all bakers, and this chappell still imployed in the way of their trade, a bake-house, though some part of this bake-house was some time turned into a starch-house.

"The time of the continuance of it in this kind, from the first letting of it to Wyat, to the restoring of it again to the church, was threescore and some odde yeeres, in the yeere of our Lord God 1624, for in this yeere the ruines and blasted estate, that the old corporation sold it to, were by the corporation of this time, repaired, renewed, well, and very worthily beautified: the charge of it for that yeere, with many things done to it since, arising to two hundred pounds.

"This, as all the former repairs, being the sole cost and charge of the parishioners."

A correspondent, E.E. inquires how it happens that the Chapel of St. Mary Magdalen, shown in all old plans of the Church, has likewise disappeared within the present century? This Chapel adjoined the South transept, and was removed during the repairs, under the able superintendence of Mr. Gwilt. It was thus described by Mr. Nightingale in 1818:

"The chapel itself is a very plain erection. It is entered on the south, through a large pair of folding doors, leading down a small flight of steps. The ceiling has nothing peculiar in its character; nor are the four pillars supporting the roof, and the unequal arches leading into the south aisle, in the least calculated to convey any idea of grandeur, or feeling of veneration. These arches have been cut through in a very clumsy manner, so that scarcely any vestige of the ancient church of St. Mary Magdalen now remains. A small doorway and windows, however, are still visible at the east end of this chapel; the west end formerly opened into the south transept; but that also is now walled up, except a part, which leads to the gallery there. There are in different parts niches which once held the holy water, by which the pious devotees of former ages sprinkled their foreheads on their entrance before the altar, I am not aware that any other remains of the old church are now visible in this chapel. Passing through the eastern end of the south aisle, a pair of gates leads into the Virgin Mary's Chapel."

From what we remember of the character of this Chapel, the lovers of architecture have little to lament in its removal. Our Correspondent, E.E., adds—"This, and not the Lady Chapel, it was, (No. 456 of The Mirror,) that contained the gravestone of one Bishop Wickham, who, however, was not the famous builder of Windsor Castle, in the time of Edward III., but died in 1595, the same year in which he was translated from the see of Lincoln to that of Winchester. His gravestone, now lying exposed in the churchyard, marks the south-east corner of the site of the aforesaid Magdalen Chapel."

SCOTTISH ECONOMY

SHAVINGS v. COAL AND PEAT

(To the Editor.)Without intending to be angry, permit me to inform your well-meaning correspondent, M.L.B. that his observations on the inhabitants of "Auld Reekie," are something like the subject of his communication "Shavings," rather superficial.

Improvidence forms no feature in the Scottish character; but your flying tourist charges "the gude folk o' Embro'" with monstrous extravagance in making bonfires of their carpenters' chips; and proceeds to reflect in the true spirit of civilization how much better it would have been if the builders' chips had been used in lighting household fires, to the obviously great saving of bundle-wood, than to have thus wantonly forced them to waste their gases on the desert air. But your traveller forgot that in countries which abound in wheat, rye is seldom eaten; and that on the same principle, in Scotland, where coal and peat are abundant, the "natives," like the ancient Vestals, never allow their fires to go out, but keep them burning through the whole night. The business of the "gude man" is, immediately before going to bed, to load the fire with coals, and crown the supply with a "canny passack o' turf," which keeps the whole in a state of gentle combustion; when, in the morning a sturdy thrust from the poker, produces an instantaneous blaze. But, unfortunately, should any untoward "o'er-night clishmaclaver" occasion the neglect of this duty, and the fire be left, like envy, to feed upon its own vitals, a remedy is at hand in the shape of a pan "o' live coals" from some more provident neighbour, resident in an upper or lower "flat;" and thus without bundle-wood or "shavings," is the mischief cured.

I hope that this explanation will sufficiently vindicate my Scottish friends from M.L.B.'s aspersion. Scotchmen improvident! never: for workhouses are as scarce among them as bundle-wood, or intelligent travellers. Recollect that I am not in a passion; but this I will say, though the gorge choke me, that M.L.B. strongly reminds me of the French princess, who when she heard of some manufacturers dying in the provinces of starvation, said, "Poor fools! die of starvation—if I were them I would eat bread and cheese first."

The next time M.L.B. visits Scotland, let him ask the first peasant he meets how to keep eggs fresh for years; and he will answer rub a little oil or butter over them, within a day or two after laying, and they will keep any length of time, perfectly fresh. This discovery, which was made in France by the great Reamur, depends for its success upon the oil filling up the pores of the egg-shell, and thereby cutting off the perspiration between the fluids of the egg and the atmosphere, which is a necessary agent in putrefaction. The preservation of eggs in this manner, has long been practised in all "braid Scotland;" but it is not so much as known in our own boasted land of stale eggs and bundle-wood.

In Edinburgh, I mean the Scottish and not the Irish capital, M.L.B. may actually eat new laid eggs a year old! How is it that this great comfort is not practised in the navy? The Scotch have also a hundred other domestic practices for the saving of the hard earned "siller;" and are far from the commission of any such idle waste as M.L.B.'s story exhibits. S.S.

P.S. Tinder-boxes are unknown in Scotland, and I am sure M.L.B. if he wants a business would as readily make his fortune by selling them, as the Yorkshireman who went to the West Indies with a cargo of great coats.

LINES

ON MY FORTY-NINTH BIRTHDAY

(For the Mirror.)On the slope of Life's decline,The landmark reached of forty-nine,Thoughtful on this heart of mineStrikes the sound of forty-nine.Greyish hairs with brown combineTo note Time's hand—and forty-nine.Sunny hours that used to shine,Shadow o'er at forty-nine.Of youthful sports the joys decline,Symptoms strong of forty-nine.The dance I willingly resign,To lighter heels than forty-nine.Yet, why anxiously repine?Pleasures wait on forty-nine.Social pleasures—joys benign—Still are found at forty-nine.With a friend to go and dine,What better age than forty-nine?Ladies with me sip their wine,Though they know I'm forty-nine.Tea and chat, and wit combine,To enliven musing forty-nine.Let harmony its chords untwine,Music charms at forty nine.O'er wasting care let croakers whine,Care we'll defy at forty-nine.Fifty shall not make me pine—Why lament o'er forty-nine.Joys let's trace of "Auld Lang Syne,"Memory's fresh at forty-nine.Then fill a cup of rosy wine,And drink a health to FORTY-NINE.W. W.SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

PHILOSOPHY OF LONDON

The QuadrantThe principle of suum cuique is felicitously enforced in that ostentatious but rather heavy piece of architecture, the Regent Quadrant, the pillars of which exhibit from time to time different colours, according to the fancy of the shop-owners to whose premises respectively they happen to belong. Thus, Mr. Figgins chooses to see his side of a pillar painted a pale chocolate, while his neighbour Mrs. Hopkins insists on disguising the other half with a coat of light cream colour, or haply a delicate shade of Dutch pink; so that the identity of material which made it so hard for Transfer, in Zeluco, to distinguish between his metal Venus and Vulcan, is often the only incident that the two moieties have in common.

SquaresThe few squares that existed in London antecedent to 1770, were rather sheep-walks, paddocks, and kitchen gardens, than any thing else. Grosvenor Square in particular, fenced round with a rude wooden railing, which was interrupted by lumpish brick piers at intervals of every half-dozen yards, partook more of the character of a pond than a parterre; and as for Hanover Square, it had very much the air of a sorry cow-yard, where blackguards were to be seen assembled daily, playing at husselcap up to their ankles in mire. Cavendish Square was then for the first time dignified with a statue, in the modern uniform of the Guards, mounted on a charger, à l'antique, richly gilt and burnished; and Red Lion Square, elegantly so called from the sign of an ale-shop at the corner, presented the anomalous appendages of two ill-constructed watch-houses at either end, with an ungainly, naked obelisk in the centre, which, by the by, was understood to be the site of Oliver Cromwell's re-interment. St. James's Park abounded in apple-trees, which Pepys mentions having laid under contribution by stealth, while Charles and his queen were actually walking within sight of him. The quaint style of this old writer is sometimes not a little entertaining. He mentions having seen Major-General Harrison "hanged, drawn, and quartered at Charing-Cross, he (Harrison) looking as cheerful as any man could in that condition." He also gravely informs us that Sir Henry Vane, when about to be beheaded on Tower Hill, urgently requested the executioner to take off his head so as not to hurt a seton which happened to be uncicatrized in his neck!

Modern BuildingWe are the contemporaries of a street-building generation, but the grand maxim of the nineteenth century, in their management of masonry, as in almost every thing else, as far as we can discover, appears to lie in that troublesome line of Macbeth's soliloquy, ending with, "'twere well it were done quickly." It is notorious that many of the leases of new dwelling-houses contain a clause against dancing, lest the premises should suffer from a mazurka, tremble at a gallopade, or fall prostrate under the inflictions of "the parson's farewell," or "the wind that shakes the barley." The system of building, or rather "running up" a house first, and afterwards providing it with a false exterior, meant to deceive the eye with the semblance of curved stone, is in itself an absolute abomination. Besides, Greek architecture, so magnificent when on a large scale, becomes perfectly ridiculous when applied to a private street-mansion, or a haberdasher's warehouse. St. Paul's Church, Covent-Garden, is an instance of the unhappy effect produced by a combination of a similar kind; great in all its parts, with its original littleness, it very nearly approximates to the character of a barn. Inigo Jones doubtless desired to erect an edifice of stately Roman aspect, but he was cramped in his design, and, therefore, only aspired to make a first-rate barn; so far unquestionably the great architect has succeeded. Then looking to those details of London architecture, which appear more peculiarly connected with the dignity of the nation, what can we say of it, but that the King of Great Britain is worse lodged than the chief magistrate of Claris or Zug, while the debates of the most powerful assembly in the world are carried on in a building, (or, a return to Westminster Hall,) which will bear no comparison with the Stadthouse at Amsterdam! The city, however, as a whole, presents a combination of magnitude and grandeur, which we should in vain look for elsewhere, although with all its immensity it has not yet realized the quaint prediction of James the First,—that London would shortly be England, and England would be London.

MorningThe metropolis presents certain features of peculiar interest just at that unpopular dreamy hour when stars "begin to pale their ineffectual fires," and the drowsy twilight of the doubtful day brightens apace into the fulness of morning, "blushing like an Eastern bride." Then it is that the extremes of society first meet under circumstances well calculated to indicate the moral width between their several conditions. The gilded chariot bowls along from square to square with its delicate patrimonial possessor, bearing him homeward in celerity and silence, worn with lassitude, and heated with wine quaffed at his third rout, after having deserted the oft-seen ballet, or withdrawn in pettish disgust at the utterance of a false harmony in the opera. A cabriolet hurries past him still more rapidly, bearing a fashionable physician, on the fret at having been summoned prematurely from the comforts of a second sleep in a voluptuous chamber, on an experimental visit to