полная версия

полная версияNotes and Queries, Number 03, November 17, 1849

Various

Notes and Queries, Number 03, November 17, 1849

TRAVELLING IN ENGLAND

I suppose that the history of travelling in this country, from the Creation to the present time, may be divided into four periods—those of no coaches, slow coaches, fast coaches, railways. Whether balloons, or rockets, or some new mode which as yet has no name, because it has no existence, may come next, I cannot tell, and it is hardly worth while to think about it; for, no doubt, it will be something quite inconceivable.

The third, or fast-coach period was brief, though brilliant. I doubt whether fifty years have elapsed since the newest news in the world of locomotive fashion was, that—to the utter confusion and defacement of the "Sick, Lame, and Lazy," a sober vehicle so called from the nature of its cargo, which was nightly disbanded into comfortable beds at Newbury—a new post-coach had been set up which performed the journey to Bath in a single day. Perhaps the day extended from about five o'clock in the morning to midnight, but still the coach was, as it called itself, a "Day-coach," for it travelled all day; and if it did somewhat "add the night unto the day, and so make up the measure," the passengers had all the more for their money, and were incomparably better off as to time than they had ever been before. But after this many years elapsed before "old Quicksilver" made good its ten miles an hour in one unbroken trot to Exeter, and was rivalled by "young Quicksilver" on the road to Bristol, and beaten by the light-winged Hirondelle, that flew from Liverpool to Cheltenham, and troops of others, each faster than the foregoing, each trumpeting its own fame on its own improved bugle, and beating time (all to nothing) with sixteen hoofs of invisible swiftness. How they would have stared if a parliamentary train had passed them, especially if they could have heard its inmates grumbling over their slow progress, and declaring that it would be almost quicker to get out and walk whenever their jealousy was roused by the sudden flash of an express.

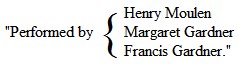

Certainly I was among those who rejoiced in the increased expedition of the fast-coach period; not because I loved, but because I hated, travelling, and was glad to have periods of misery abridged. I used to listen with delight to the stories of my seniors, and to marvel that in so short a space of time so great an improvement had been made. One friend told me that in earlier life he had travelled from Gloucester to Hereford in a coach, which performed the journey of about thirty miles between the hours of five in the morning and seven in the evening. I took it for granted that they stopped on the road to dine, and spent a long afternoon in smoking, napping, or playing at bowls. But he would not acknowledge anything of the kind, and the impression on his mind was that they kept going (such going as it was), except during the time necessarily expended in baiting the horses, who, I think, were not changed—unless indeed it were from bad to worse by fatigue. Another friend, a physician at Sheffield, told me that one of the first times (perhaps he may have said, the first) that a coach started for London, he was a passenger. Without setting out unreasonably early in the morning, or travelling late at night they made such progress, that the first night they lay at Nottingham, and the second at Market Harborough. The third morning they were up early, and off at five o'clock; and by a long pull and a strong pull through a long day, they were in time to hear Bow Church clock strike eleven or twelve (I forget which) as they passed through Cheapside. In fact such things have always seemed to me to be worth noting, for you never can tell to what extent, or even in what direction, they may throw some little ray of light on an obscure point of history. On this principle I thought it worth while to copy an original bill which lately fell into my hands. Many such have been reprinted, but I am not aware that this one has; and as what is wanted is a series, every little may help. It is as follows:—

"YORK Four Dayes

"Stage-Coach

"Begins on Monday the 18 of March 1678.

"All that are desirous to pass from London to York, or return from York to London or any other Place on that Road; Let them Repair to the Black Swan in Holborn in London and the Black Swan in Cony-Street in York.

"At both which places they may be received in a Stage-Coach every Monday, Wednesday and Friday, which performs the whole journey in Four days (if God permit) and sets forth by Six in the Morning.

"And returns from York to Doncaster in a Forenoon, to Newark in a day and a half, to Stamford in Two days, and from Stamford to London in Two days more.

But I cannot deny that, while I have listened to, and rejoiced in, these stories, I have had some doubt whether full justice has been done to the other side of the question. I have always felt as if I had a sort of guilty knowledge of one contradictory fact, which I learned between twenty and thirty years ago, and which no one whom I have yet met with has been able to explain. For this reason I am desirous to lay it before you and your readers.

Just one hundred years ago—that is to say, on Sunday, the 10th of August, 1749—two German travellers landed at Harwich. The principal one was Stephen Schultz, who travelled for twenty years through various parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa, in the service of the Callenberg Institution at Halle, of which he was afterwards Director, being at the same time Pastor of St. Ulrich's Church in that city, where his picture is (or was about twenty years ago) to be seen affixed to the great pillar next the organ. It represents him as an elderly divine in a black cap, and with a grave and prediger-like aspect; but there is another likeness of him—an engraved print—in which he looks more like a Turk than a Christian. He is dressed in a shawl turban, brickdust-red mantle, and the rest of the costume which he adopted in his Eastern travels. Our business, however, is with his English adventures, which must, I think, have astonished him as much as anything that he met with in Arabia, even if he acted all the Thousand and One Nights on the spot. As I have already said, he and his companion (Albrecht Friedrich Woltersdorf, son of the Pastor of St. George's Church in Berlin), landed at Harwich on Sunday, August 10. They staid there that night, and on Monday they walked over to Colchester. There (I presume the next morning) they took the "Land-Kutsche," and were barely six hours on the road to London.

This statement seems to me to be so at variance with notorious facts, that, but for one or two circumstances, I should have quietly set it down for a mistake; but as I do not feel that I can do this, I should be glad to obtain information which may explain it. It is no error of words or figures, for the writer expresses very naturally the surprise which he certainly must have felt at the swiftness of the horses, and the goodness of the roads. He was a man who had seen something of the world, for he had lived five-and-thirty years, thirteen of which had elapsed since he began his travels. As a foreigner he was under no temptation to exaggerate the superiority of English travelling, especially to an extent incomprehensible by his countrymen; and, in short, I cannot imagine any ground for suspecting mistake or untruth of any kind.1

I have never been at Colchester, but I believe it is, and always was, full fifty miles from London. Ipswich, I believe, is only eighteen miles farther; and yet fifteen years later we find an advertisement (Daily Advertiser, Thursday, Aug. 30, 1764), announcing that London and Ipswich Post Coaches on steel springs (think of that, and think of the astonished Germans careering over the country from Colchester without that mitigation), from London to Ipswich in ten hours with Postillions, set out every morning at seven o'clock, Sundays excepted, from the Black Bull Inn, in Bishopsgate Street.

It is right, however, to add that the Herr Preniger Schultz and his companion appear to have returned to Colchester, on their way back to Germany, at a much more moderate pace. The particulars do not very exactly appear; but it seems from his journal that on the 16th of September they dined with the Herr Prediger Pittius, minister of the German Church in the Savoy, at twelve o'clock (nach teutscher art, as the writer observes). They then went to their lodging, settled their accounts, took up their luggage, and proceeded to the inn from which the "Stäts-Kutsche" was to start; and on arriving there found some of their friends assembled, who had ordered a meal, of which they partook. How much time was occupied in all this, or when the coach set out, does not appear; but they travelled the whole night, and until towards noon the next day, before they got to Colchester. This is rather more intelligible; but as to their up-journey I really am puzzled, and shall be glad of any explanation.

Yours, &c.

G.G.

SANUTO'S DOGES OF VENICE

Mr. Editor,—Among the well-wishers to your projected periodical, as a medium of literary communication, no one would be more ready to contribute to it than myself, did the leisure I enjoy permit me often to do so. I have been a maker of Notes and Queries for above twenty-five years, and perhaps should feel more inclined to trouble you with the latter than the former, in the hope of clearing up some of the many obscure points in your history, biography, and poetical literature, which have occurred to me in the course of my reading. At present, as a very inadequate specimen of what I once designed to call Leisure Moments, I beg to copy the following Note from one of my scrap-books:—

In the year 1420, the Florentines sent an embassy to the state of Venice, to solicit them to unite in a league against the ambitious progress of Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan; and the historian Daru, in his Histoire de Venise, 8vo., Paris, 1821, has fallen into more than one error in his account of the transaction. Marino Sanuto, who wrote the lives of the Doges of Venice in 1493 (Daru says, erroneously, some fifty years afterwards), has preserved the Orations made by the Doge Tomaso Mocenigo, in opposition to the Florentine proposals; which he copied, according to his statement, from a manuscript that belonged to the Doge himself. Daru states, that the MS. was communicated to him by the Doge; but that could not be, since the Doge died in 1423, and Sanuto was not born till 1466. An abridged translation of these Orations is given in the Histoire de Venise, tom. ii, pp. 289-311.; and in the first of these, pronounced in January, 1420 (1421, Daru), he is made to say, in reference to an ambassador sent by the Florentines to the Duke of Milan, in 1414, as follows: "L'ambassadeur fut un Juif, nommé Valori, banquier de sa profession,", p. 291. As a commentary on this passage, Daru subjoins a note from the Abbé Laugier, who, in his Histoire de Venise, liv. 21., remarks, 1. That it appears strange the Florentines should have chose a Jew as an ambassador; 2. That his surname was Bartolomeo, which could not have been borne by a Jew; 3. That the Florentine historian Poggio speaks of Valori as having been one of the principal members of the Council of Florence. The Abbé thence justly concludes, that the ambassador could not have been a Jew; and it is extraordinary that Daru, after such a conclusive argument, should have admitted the term Jew into his text. But the truth is, that this writer (like many others of great reputation) preferred blindly following the text of Sanuto, as printed by Muratori2, to the trouble of consulting any early manuscripts. It happens, however, that in a manuscript copy of these Orations of Mocenigo, written certainly earlier than the period of Sanuto, and preserved in the British Museum, MS. Add. 12, 121., the true reading of the passage may be found thus:—"Fo mandato Bartolomio Valori, homo richo, el qual viveva de cambij." By later transcribers the epithet richo, so properly here bestowed on the Florentine noble, was changed into iudio (giudeo), and having been transferred in that shape into Sanuto, has formed the groundwork of a serious error, which has now existed for more than three centuries and a half.

FREDERICK MADDEN.British Museum, Nov. 7. 1849

LETTERS OF LORD NELSON'S BROTHER IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE BATTLE OF TRAFALGAR

[The following letters will be best illustrated by a few words derived from the valuable life of our great naval hero lately published by Mr. Pettigrew. Besides his last will, properly so called, which had been some time executed, Lord Nelson wrote and signed another paper of testamentary character immediately before he commenced the battle of Trafalgar. It contained an enumeration of certain public services performed by Lady Hamilton, and a request that she might be provided for by the country. "Could I have rewarded those services," Lord Nelson says, "I would not now call upon my country; but as that has not been in my power, I leave Emma Hamilton, therefore, a legacy to my king and country, that will give her ample provision to maintain her rank in life." He also recommended to the beneficence of his country his adopted daughter. "My relations," he concludes, "it is needless to mention; they will of course be amply provided for."

This paper was delivered over to Lord Nelson's brother, together with his will. "Earl Nelson, with his wife and family, were then with Lady Hamilton, and had indeed been living with her many months. To their son Horatio, afterwards Viscount Trafalgar, she was as attentive as a mother, and their daughter had been almost exclusively under her care for education for six years. The Earl kept the codicil in his pocket until the day 120,000l. was voted for him by the House of Commons. On that day he dined with Lady Hamilton in Clarges Street, and learning at table what had been done, he brought forth the codicil, and throwing it to Lady Hamilton, coarsely said, she might now do with it as she pleased."—Pettigrew's Memoirs of Nelson, ii. 624, 625. Lady Hamilton took the paper to Doctors' Commons, where it stands registered as a codicil to Nelson's will. A knowledge of these circumstances is necessary to the full understanding of our correspondents communication.]

Sir,—The following letters may be found interesting as illustrative of the private history of Lord Nelson, to which public attention has been strongly drawn of late by the able work of Mr. Pettigrew. The letters were addressed by Earl Nelson to the Rev. A.J. Scott, the friend and chaplain of the fallen hero.

18, Charles Street, Berkeley Square,

Dec. 2. 1805.

Dear Sir,—I am this day favoured with your obliging letter of October 27.3 The afflicting intelligence you designed to prepare me for had arrived much sooner; but I am duly sensible of the kind motive which inducted this mark of your attention and remembrance.

The King has been pleased to command that his great and gallant servant shall be buried with funeral honours suitable to the splendid services he rendered to his country, and that the body shall be conveyed by water to Greenwich, in order to be laid in state. For myself I need not say how anxious I am to pay every tribute of affection and of respect to my honoured and lamented brother's remains. And it affords me great satisfaction to learn your intention of accompanying them till deposited in their last earthly mansion. The coffin made of the L'Orient's mast will be sent to Greenwich to await the arrival of the body, and I hope there to have an opportunity of making my acknowledgments in person.

Believe me, dear Sir,

Your faithful friend, and obedient humble servant,

NELSON.

I beg the favour of your transmitting to me by the first safe opportunity such of my dear brother's papers (not of a public nature) as are under your care, and of making for me (with my sincere regards and kind compliments) to Captain Hardy the like request.

Please to let me hear from you the moment you arrive at Portsmouth and direct to me as above, when I will send you any further directions I may have received from ministers.

18 Charles Street, Berkeley Square,

Dec. 6. 1805.

My dear Sir,—I have this moment received your kind letter. I do not know I can add any thing to my former letter to you, or to what I have written to Captain Hardy. I will speak fully to Mr. Chevalier4 before he leaves me.

Your faithful and obliged humble servant,

NELSON.

It will be of great importance that I am in possession of his last will and codicils as soon as possible—no one can say that it does not contain among other things, many directions relative to his funeral.

18 Charles Street, Berkeley Square,

Dec. 13. 1805.

Dear Sir,—I have been to the Admiralty, and I am assured that leave will be sent to you to quit the ship, and follow the remains of my dear brother when you please. We have determined to send Mr. Tyson with the coffin to the Victory, when we know she is at the Nore. He, together with Captain hardy and yourself, will see the body safely deposited therein. I trust to the affection of all for that. The Admiralty will order the Commissioner's yacht at Sheerness to receive it, and bring it to Greenwich. I suppose an order from the Admiralty will go to Captain Hardy to deliver the body to Mr. Tyson, and you will of course attend. But if this should be omitted by any mistake of office, I trust Captain Hardy will have no difficulty.

There is no hurry in it, as the funeral will not be till the 10th or 12th of January.

We do not wish to send Tyson till we have the will and codicil, which Captain Hardy informed me was to come by Captain Blackwood from Portsmouth on Tuesday last. We are surprised he is not here. Compts. to Captain Hardy. Write to me as soon as you get to the Nore, or before, if you can.

Believe me, yours faithfully,

NELSON

Excuse this hasty and blotted scrawl, as I have been detained so long at the Admiralty that I have scarce time to save the Post.

Canterbury,

Dec. 26, 1805

Dear Sir,– I received your letters of the 23rd and 25th this morning. I am glad to hear the remains of my late dear and most illustrious brother are at length removed to Mr. Peddieson's coffin, and safely deposited in Greenwich Hospital. Your kind and affectionate attention throughout the whole of this mournful and trying scene cannot fail to meet my sincere and grateful thanks, and that of the whole family. I am perfectly satisfied with the surgeon's reports which have been sent to me, that every thing proper has been done. I could wish to have known what has been done with the bowels—whether they were thrown overboard, or whether they were preserved to be put into the coffin with the body. The features being now lost, the face cannot, as Mr. Beatty very properly observes, be exposed; I hope therefore everything is closed and soldered down.

I wrote to Mr. Tyson a few days ago, and should be glad to hear from him. I mean to go towards London about the 1st, 2nd or 3rd of Jan (the day not yet fixed), and call at Greenwich for a moment, just to have a melancholy sight of the coffin, &c. &c., when I hope I shall see you.

I shall be glad to hear from you as often as you have any thing new to communicate, and how the preparations go on. Every thing now is in the hands of government, but, strange to tell, I have not yet heard from the Herald's Office, whether I am to attend the procession or not.

Believe me,

Your much obliged humble servant,

NELSON.

The codicil referred to in these letters proved to be, or at least to include, that memorable document which the Earl suppressed, when he produced the will, lest it should curtail his own share of the amount of favour which a grateful country would be anxious to heap on the representative of the departed hero. By this unworthy conduct the fortunes of Lady Hamilton and her still surviving daughter were at once blighted.

The Earl as tightly held all he had, as he grasped all he could get. It was expected that he would resign his stall at Canterbury in favour of his brother's faithful chaplain and when he "held on" notwithstanding his peerage and riches, he was attacked in the newspapers. The following letter is the last communication with which Dr. Scott was honoured, for his work was done:—

Canterbury, May 28, 1806.

Sir,—I am glad to find, by your letter, that you are not concerned in the illiberal and unfounded paragraphs which have appeared and daily are appearing in the public prints.

I am, Sir, your very humble servant,

NELSON.

The Rev. Dr. Scott.

The above have never been printed, and I shall be glad if they are thought worthy of a place in your very useful and interesting periodical. I am, Sir, &c.,

ALFRED GATTY.Ecclesfield, 7th Nov. 1849.

MISQUOTATIONS

Mr. Editor,—The offence of misquoting the poets is become so general, that I would suggest to publishers the advantage of printing more copious indexes than those which are now offered to the public. For the want of these, the newspapers sometimes make strange blunders. The Times, for instance, has lately, more than once, given the following version of a well-known couplet:—

"Vice is a monster of so frightful mien,As to be hated needs but to be seen."The reader's memory will no doubt instantly substitute such hideous for "so frightful," and that for "as."

The same paper, a short time since, made sad work with Moore, thus:—

"You may break, you may ruin the vase if you will,But the scent of the roses will hang by it still."Moore says nothing about the scents hanging by the vase. "Hanging" is an odious term, and destroys the sentiment altogether. What Moore really does say is this:—

"You may break, you may ruin the vase if you will,But the scent of the roses will cling round it still."Now the couplet appears in its original beauty.

It is impossible to speak of the poets without thinking of Shakspeare, who towers above them all. We have yet to discover an editor capable of doing him full justice. Some of Johnson's notes are very amusing, and those of recent editors occasionally provoke a smile. If once a blunder has been made it is persisted in. Take, for instance, a glaring one in the 2nd part of Henry IV., where, in the apostrophe to sleep, "clouds" is substituted for "shrouds."

"Wilt thou, upon the high and giddy mast,Seal up the ship-boy's eyes, and rock his brainsIn cradle of the rude imperious surge,And in the visitation of the winds,Who take the ruffian billows by the top,Curling their monstrous heads, and hanging themWith deafening clamours in the slippery clouds,That with the hurly death itself awakes?"That shrouds is the correct word is so obvious, that it is surprising any man of common understanding should dispute it. Yet we find the following note in Knight's pictorial edition:—

"Clouds.—Some editors have proposed to read shrouds. A line in Julius Cæsar makes Shakspere's meaning clear:—

"'I have seenTh' ambitious ocean swell, and rage, and foam,To be exalted with the threatening clouds.'"Clouds in this instance is perfectly consistent; but here the scene is altogether different. We have no ship-boy sleeping on the giddy mast, in the midst of the shrouds, or ropes, rendered slippery by the perpetual dashing of the waves against them during the storm.

If in Shakspeare's time the printer's rule of "following copy" had been as rigidly observed as in our day, errors would have been avoided, for Shakspeare's MS. was sufficiently clear. In the preface to the folio edition of 1623, it is stated that "his mind and hand went together; and what he thought he uttered with that easinesse that wee have scarse received from him a blot in his papers."

D***N**R.8th Nov. 1849.

HERBERT AND DIBDIN'S AMES