Полная версия

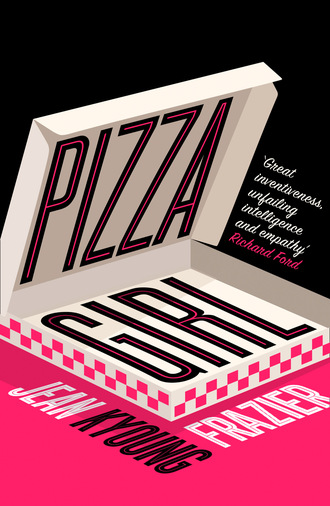

Pizza Girl

Dad had died a week earlier. Soon, Billy was sitting across from me in a circle of other people who were dealing with Grief and Loss of a Loved One. The meetings were held in the local church every Wednesday at 5:00 p.m. The cookies were stale. Fortunately, the coffee was strong. We sat and listened as people wept and worried that they’d never be the same. Billy and I were the only two who never cried, although he did look sad, different, unlike the large, laughing boy whose warm presence I’d taken for granted.

One day after the meeting, he asked me if I liked ice cream. I said not really, but that I would go with him.

We sat in silence as he ate three separate cones. I was about to tell him that he could’ve saved money and just gotten a triple scoop when he blurted out that he felt bad that he didn’t feel more bad.

“Things really haven’t been so different since they died,” he said, looking down at his empty, sticky hands. “I didn’t see them much. They always seemed to love each other more than me, were always going on romantic dates or taking trips together. I kind of felt like their third wheel, an afterthought. The house has always been quiet.” He looked at me then, only for a second. “I just see all those people in there sobbing and I’m so damn jealous.” He chewed on his lip, began shredding the napkin in front of him, and I felt something in me twist and soften—I had the same nervous habit. “Sorry,” he said. “That was fucked up.”

I noticed his shoulders then, how strong they looked, like they were made of beef and steel. I pictured trees, mountains, boulders, birds’ nests, all of the Los Angeles skyline resting upon them.

I grabbed both of his hands in mine, tight. “Do you want to come back to my place?”

I LOCKED THE CAT in my room and went downstairs. Mom was knitting tiny sweaters in neutral colors while Billy was in the kitchen making pajeon shaped like barnyard animals. For the past couple weeks, Mom had been teaching Billy how to make basic Korean dishes: “The baby can have your hair. He’s going to have our taste buds.”

Mom came to the United States after her mom’s brother wrote to her that he’d found the promised land: Champaign-Urbana, Illinois. He owned a convenience store and could always use more help. After months of paperwork and waiting in long lines, Mom and her family were on a fourteen-hour flight straight to Chicago.

She was seventeen when they got there—young enough to be molded, not so young that she hadn’t already begun to want certain things, big things. She worked long hours at the convenience store, and when it was slow, studied English, determined to lose her accent, dreamed of the University of Illinois. All the UI students who came in to buy candy, cigarettes, condoms, and booze seemed so attractive and happy. She became obsessed with Americanness, wanted nothing more than to be a part of the red, the white, the blue.

One of the university students came in every morning to buy a pack of Luckies and two forties. He was tall and broad and 100 percent American, always smiled at her, asked her how her day was going, remembered her name, said it with a soft Midwestern twang as he walked out of the store. At night, he’d come back, buy two more forties, and wait until closing. They’d sit on the bus bench outside, talking for hours, passing the bottle back and forth, even though Mom hated beer.

Two months later, they were moving to Los Angeles. He wanted to write movies and make millions. She wanted him and to wake up every morning, look out her window, see the Pacific Ocean. Eleven months later, I was born.

I stopped on the edge of the staircase and stared at Mom as she knitted and thought about how our house was thirty minutes from the beach.

She looked up and noticed me, smiled wide. “How are my babies doing?” Billy turned around and smiled too. They stopped what they were doing and got up to hug me. They formed a warm, loving wall around me, rubbed my belly, and whispered to it. I couldn’t hear what they were saying.

We sat down and they started talking about what they always talked about.

First, they asked how I was feeling, and after I gave my usual “Fine, good. Yeah, I’m good,” they launched into more important subjects—what gender the baby would be (they both were sure it was going to be a boy), strong manly names (John, Matthew, Jacob, other Bible men, even though we weren’t religious), color of the nursery (a classic blue or a bold red), potential godfathers and godmothers (lots of names of family members I didn’t know), should we already start saving for private school (absolutely, yes), etc.

I nodded and smiled, said “uh-huh” at the right times. I was feeling fine until Mom brought up the name “Adam,” perfect for a first child.

My face stayed normal and I managed to eat more than half my plate, but I was gone, done for; my mind was on Jenny Hauser’s ponytail.

HER PONYTAIL was the longest I’d ever seen on a woman her age.

Most moms in my neighborhood kept their hair short or bobbed, muted, as if to have physical proof of their seriousness, their superior mothering ability—my thank-you card is nicer than your thank-you card, don’t you dare try and sign up for more Neighborhood Watch shifts than me, this marijuana is medicinal. Jenny’s hair spilled down her back, didn’t stop until it was hovering just above her butt.

She had to be at least forty, probably closer to forty-five. Her body looked soft, once fit. Her jeans were baggy and shapeless and there was a stain on the collar of her shirt. I hoped that the stain was new. It seemed more likely that she’d been wearing the same shirt for several days. There were lines around her eyes and mouth, two deeper ones on her forehead. I wanted to touch them with my fingertips, smooth them out. When she spoke, her voice cracked on the first word, like she hadn’t said anything out loud in a while.

“Jesus Christ,” she’d said. “Your uniforms are truly terrible.”

“I know.”

“Green and orange. Like Kermit the Frog fucked a pumpkin.”

“The Hulk ate a bunch of Doritos and took a shit.”

She laughed and her eyes got squinty, crinkled at the edges. I didn’t want to smooth out all her lines. “Truly, though, thank you for this,” she said. “I can’t believe you actually came.”

The air turned thick and I found it impossible to look her in the eye. I wanted to be wearing a big jacket and a hat I could pull down low. I mumbled, “No problem,” and handed her the pizza.

I was about to turn and sprint back to my car when she said, “Oh! I have to pay you!” She slapped her forehead. “And tip you! I absolutely have to tip you. Hold on, my wallet is lying around somewhere.”

She disappeared into her house and I stood there awkwardly, shifting my weight from foot to foot. I planned on politely waiting there, staying outside, but the door hung wide open and something caught my eye.

The home’s entrance was pristine, a word I’d never used to describe anything before. An intricate Persian rug, shoes lined up evenly on both sides, a center table topped with a vase of real flowers, fancy flowers, not corner-market $9.99-for-a-dozen roses, all of this underneath a crystal chandelier—none of this was what interested me.

The front of the house may have been pristine, but just beyond, into the living room, it was chaos.

There could’ve been another beautiful rug, there could’ve just been carpet, it was impossible to tell. Clothes covered every inch of the floor. On the couch there was an empty bag of Hot Cheetos, a half-eaten salad, a tub of cream cheese. The table was crowded with magazines and paper plates covered in various pools of paint. Seven chairs looked like they’d been brought in from the dining room and were serving as easels for her paintings.

I had never been alone in someone else’s house. Slow steps forward, a pause after each, a moment to consider the wrongness of what I was doing—how rude of me to violate her private space with my eyes, to let the bottoms of my shoes sink into her carpet and leave behind the filth of where I’d been, she would be back at any moment, what would I say then? The next minute I’d see something new that would wipe the guilt from my thoughts and leave behind only curiosity, bright and shiny and begging to be stroked—I couldn’t stop thinking about how, at one point or another, everything in the room had been touched by her hands. I walked through Jenny’s living room turning my head left and right, fists clenched at my sides.

I went to the nearest chair and inspected its painting closely—it was terrible. They were all terrible. Two were rudimentary portraits of turtles, two were blocky houses in open fields, one was full of unintelligible blobs, one was just three different shades of blue, the last was blank, still lovely with possibility.

“Yikes. Hi.”

I turned around to see Jenny standing behind me, a twenty in hand, and a look I couldn’t read on her face. We stood facing each other in silence among the clutter and paintings. All the apologies I could think of sounded more like pleas—I’m sorry, please, I do things without thinking and I don’t know how to stop. Before I could say anything, she surprised me again by laughing. “So—I guess now you really think I’m crazy.”

She cleared her throat. “So let me explain.”

She pointed to the floor. “Old T-shirts to catch any paint that I spill.”

She pointed to the couch. “I actually attempted a healthy lunch, but my mouth got bored. Have you ever tried dipping your Hot Cheetos in cream cheese? What? No? Do it. One-hundred-Michelin-star rating.” She paused. “Now, the paintings. What do you think?”

“Oh. Well.”

She laughed again and I found myself becoming used to the sound. “It’s okay,” she said. “You don’t have to worry. This isn’t a hobby of mine. I have no secret burning desire to become a painter. I was just in my son Adam’s room earlier and I realized he had no decorations on his walls and I thought I’d try and make some for him, brighten the space a little. As you can see, I forgot a very important detail.” She spread her arms wide. “I suck at art.”

“I like that one turtle,” I said. “His head is weird and dented. Like he got hit with something hard.”

“Yeah? Thanks. Turtles are Adam’s favorite animal. He wants to go to Hawaii so he can swim with them.”

I checked my watch; I’d been gone for way too long. I was about to ask for the money when I felt my lunch rising in me—a slice of pizza and a Snickers bars—ran toward a closed door that looked like it would lead to a bathroom, but was actually to a closet. I sunk down to my knees, grabbed the least expensive-looking thing, a rain boot, and puked in it.

The puke was watery—I could see a full, undigested circle of pepperoni—I puked some more and felt a hand on my shoulder, turned around to see Jenny hovering behind me. “I’m sorry,” I said, “I—”

“You’re pregnant.” She helped me off the ground, her smile stretched and warm, and I wished that a detail other than my pregnancy had made her look that way. “Congratulations! You doing this favor for me is proof you’re going to be a great mom.”

I almost puked more, but swallowed it down.

I didn’t know if I was noticeably showing yet and I was doing my best not to find out. In the mornings, before I showered, I’d undress with my back to the mirror. When I walked, I’d keep my head up and eyes focused straight ahead, I avoided looking down. It made my palms itch to think about the day when I wouldn’t be able to fit into any of my clothes.

My hands went to my belly as if to cover it. “Thanks.”

She frowned. “You’re not excited.” It wasn’t a question. She said it firmly, unblinking, a statement.

I lied often. It was just simpler that way. As a little kid, I remember being told repeatedly that lying was bad, lying never fixed anything, Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves and never lied. But no one ever told me how wonderful and easy it was to lie, how many conversations it would save me from and the stares it would avert—“Yeah, I’m fine!” “What? No, I’m not mad!” “Don’t worry, it’s okay!”—and did Abraham Lincoln really never, ever lie? In bed at night during the Civil War, did he toss and turn and soak his sheets with sweat and eventually wake Mary Todd to tell her, “Hold me, I’m scared, I think I fucked up,” or did he lie awake and sweat quietly, working his hardest to remain still, to keep his mouth shut, to let Mary Todd sleep soundly and unaware?

Lying was simpler. I repeated this in my head over and over as I stood in Jenny’s living room looking at everything except her—each shitty painting, the blank canvas, the tub of cream cheese, the old T-shirts on the ground. I kept returning to one T-shirt. It was purple and had a large cobra head in the center with the words “Excellence is” underneath. The rest of the sentence was cut off by a Hawaiian shirt.

“Hey, you okay?”

I looked away from the cobra and back to Jenny. She was staring at me with wide eyes, her mouth hanging open a little. I noticed a piece of lettuce stuck between her bottom front teeth and I desperately wanted to reach over and pull it out, let my fingers linger in her mouth and spit, and I knew I wouldn’t be able to lie, even if it was easier.

“No,” I said. “I’m not excited.”

She looked away from me and I regretted saying anything, regretted that I spoke truth and it revealed my ugliness, let it breathe and writhe in the daylight. Then she looked back at me and said, “Good.”

“What?”

“It’s good you’re not excited. Or it’s good you know you’re not excited.” Her voice was different now, more like it was when I first heard it on the phone—low, trembling, a voice standing on the top of a ladder, the lip of a skyscraper, the peak of a mountain, a voice that can’t help but look over the edge even though it knows this will serve only as a reminder that it’s a long way down, a voice that needed to be cradled, tucked in gently each night. “People will always love telling you how you’re supposed to be feeling and it will always make you feel less than when you don’t feel it. I’m sorry if I was being one of those people.” She shook her head. “How old are you?”

“Eighteen.”

“I’ll tell you what I wish someone told me when I was eighteen—it never goes away.”

“What is ‘it,’ exactly?”

“All of it, any of it, just it.” Suddenly, she reached out and pushed a loose strand of my hair behind my ear. “Jesus, you’re so young. Of course you’re not excited.”

She kept staring at me and I was worried that she was going to ask more, that I would dump the weight of my life among her living-room clutter. She just turned, grabbed the turtle painting, and handed it to me. “For the baby. Boy or girl, everyone likes turtles.”

I wasn’t much of a crier—Billy and I had rented Toy Story 2 last week and the collar of his shirt was damp by the end, mine dry. As I took that shitty painting I felt weirdly close to tears.

“Here’s money for the pizza, keep the change.” She handed me a twenty and pulled out another, pressed it firmly into my palm. “And a little extra for you, my savior.”

She walked me to the front door and hugged me and I didn’t mind. She smiled and I wanted to bottle it up, pour it over my morning cereal. “Take care, Pizza Girl.”

The door shut and I stared at it, tried to come up with reasons to knock and bring her back.

IT WAS A BLESSING I didn’t get into a car accident. I spent the rest of my shift in a daze. My hands and feet felt and behaved like bricks. I knocked over a stack of boxes and dropped a napkin dispenser I was trying to refill. As Darryl bent down to help me clean up, he asked me if I’d taken pulls from his Bacardi.

I mixed up orders. Drew Herold got Patty Johnston’s Meat Lovers, extra bacon. Patty Johnston got Drew Herold’s Very Veggie, no sauce. “You might as well just get a salad,” she said, shaking her head, inspecting a mushroom between her fingers. She was nice, an older mom type who looked like she was used to dealing with youthful incompetence. She didn’t mind having to wait while I drove back to retrieve her pizza, just told me to include garlic bread sticks for free next time she called in. Drew Herold was less nice, told me that meat was murder, he’d be calling Domino’s in the future.

When I got back to the shop, I went to the bathroom and didn’t notice the seat was up. There was toilet water on my pants as Peter yelled at me. Driving home, I missed the turn for my street three times. I kept getting distracted by lamppost lights—I saw Jenny standing underneath each one. She was still lovely, even under their harsh orange glow.

AT NIGHT, after Billy was snoring in my ear and I heard Mom flick off the TV and double-lock the front door, I’d run my hands through Billy’s hair twice and then quietly get out of bed. I’d tiptoe down the stairs and into the backyard, walk across the lawn, and go inside Dad’s shed.

In his last years, Dad spent most of his time in here. When he got home from whatever his current job was, when Mom or I pissed him off, when he just needed a breath, some “Me Time,” he’d throw open the screen door and stomp across the lawn, lock himself in the shed for hours.

The shed was always padlocked. He repeated over and over that Mom and I were forbidden to go inside. A little after he died, I got a hammer and swung at the lock until it broke off.

I didn’t know what to expect, but I realized then a part of me hoped that whenever he went into the shed he’d feel bad about what he’d said, how he acted, his boozy, sour breath. He’d feel bad and he’d grab his toolbox or notebook and try to make us something to apologize, would write long letters to us promising to be a better man. I pictured him whittling little sculptures, painting them bright, hopeful colors. His letters would contain beautiful, flowery language.

When I went inside there were no tools, or papers, or paints. There was just an old armchair, a small TV on a table barely big enough to support it, a mini-fridge. Empty beer cans and cigarette butts covered most of the floor. There were a pile of old newspapers and a foam football in the corner.

I thought about going back into the house and getting a book of matches, watching the shed burn before my eyes. I didn’t. I sat in the armchair and cried for the first and only time since he died.

Ever since Billy and I decided we’d be keeping the baby, I’d been coming to the shed most nights. I’d sit in the armchair and flick on the TV to the infomercial channel—there was something weirdly peaceful about people enthusiastically trying to sell you things. After a while, I’d open the fridge and pull out a beer. It was lite beer, I reasoned, basically water. I would only have one, sometimes two if the day had been long and my head and body both felt heavy. I’d drink slowly, try and empty my mind, focus on the infomercials and how much better my life could be if I had a Snuggie, or a Shake Weight, or Ginsu Steak Knives—I’d be warm, fit, and able to slice through anything.

It was the best part of my days.

I was halfway through my third beer when I remembered. I walked out of the shed and to the front of the house and unlocked the trunk of my car, grabbed Jenny’s painting.

There were no nails to hang it, so I just leaned the misshapen turtle against the wall with the TV. It looked good there.

3

“AT TWELVE WEEKS, the baby is the size of a plum.”

The clinic doctor told me this with a smile as he squirted gel onto my belly. The gel was a translucent blue, felt slimy and cold. Alien spit, I thought.

“Like what type of plum? And how ripe is it?” I shivered as I watched him spread the gel around. “At the supermarket, plums come in lots of different sizes.”

The doctor standing above me was an old man with hair coming out of his nose and ears. His hands looked older than the rest of him—large and gnarled, veins popping out, deeply lined palms—I wondered when the last time he had sex was, what those hands felt like against bare thighs. His name tag literally read Dr. Oldman and I would’ve laughed if I hadn’t been lying on my back, shirt up, sweaty and alone. I couldn’t stop imagining a plum in my stomach.

“You’re a funny girl,” he said.

I imagined the plum growing arms and legs and trying to communicate with me. I couldn’t or wouldn’t understand. The plum quickly gave up on me and started banging its tiny fists against the inner walls of my stomach, dug its teeth into me, and drew blood. I shivered again.

The night before, Billy had rubbed my shoulders and offered to come with me, but the appointment was at nine. Landscaping crews did their biggest jobs before the sun reached its full power—a few parks, schools, one cemetery—since hard work was a little less hard when sweat wasn’t pouring into your eyes, the back of your neck wasn’t red and burnt, thirstiness was a feeling that started in your throat and spread to your mind. I kissed both of Billy’s eyelids and told him that I would be fine, he shouldn’t skip work, we couldn’t afford that.

The money Billy’s parents left him had been huge in helping us with bills, groceries, a fun trip to the movies here and there, and we both tried not to think about how the total was deflating at a rapid rate. Mom was a checker at Kmart and the job sucked—she’d been working there for ten years and had only just received her first raise, a dollar more per hour—but we were lucky they provided insurance. I held Billy’s large, sweet head between my hands and told him to go to work, I’d be fine, would make sure to bring home the first picture of Billy Jr.

As I lay there watching Dr. Oldman set up the ultrasound equipment, I tuned out his small talk about his daughters—there were five of them, all named after famous mountain ranges—and forced myself to wonder why I really didn’t want Billy to come with me to the appointment.

Yes, it was true that there was a never-ending list of things Billy and I needed and that most of those things were tied to money. At night we’d strip naked and cuddle in bed, taking turns being big spoon, and going on and on about how dope life would be if we had a bottomless bank account.

No question, we’d quit our jobs. Mom had been good to us, we’d buy her her own place, one with a front- and backyard, a kitchen worthy of her skill, finally by the ocean, close enough that if she opened the windows sand would get blown in by the sea breeze. With Mom taken care of and our schedules open, next we’d buy a new car, something fast and flashy and gas-inefficient, red or yellow, maybe a sharp electric blue, good-fucking-bye to that goddamn Festiva. Billy had a book of U.S. maps. We’d pore over the pages and debate where to drive first, where we wanted the baby to be born—“How cool would it be to say you were from Zzyzx, California?” We’d go back and forth for a while until Billy would shrug and smile. “Let’s just go everywhere, literally every city in America. I want to go everywhere with you. The baby will be cool no matter where he’s from.”

This was all talk, though, something to occupy our minds and fill our sleep with big, bright images. Billy was content with our life, what we had was more than enough for him, and I was pretty sure it was enough for me too. We would find ways to make money and get by. He could’ve definitely skipped work to come with me to our baby’s twelve-week ultrasound.

In the week leading up to the appointment, every time I pictured Billy standing by my side and holding my hand, sweat would begin to collect on my upper lip. Mom always told me that this was how she knew when I was nervous, Dad used to nervous-sweat too. She remembered on their wedding day standing at the altar before him, hoping that he’d wipe his lip with the back of his hand before he kissed her.

Even just picturing Billy next to me at that moment in the clinic, I could feel the lip sweat forming. He would’ve been his lovely, charming self, making small talk right back with Dr. Oldman, asking polite questions while also being funny—“What’re your daughters’ names? I can only guess one: Sierra Nevada. You didn’t name one Kilimanjaro, did you?” Their joint laughter echoed in my head, and I felt the pits of my shirt begin to grow dark and wet.