полная версия

полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 53, March, 1862

Various

The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 09, No. 53, March, 1862 / A Magazine of Literature, Art, and Politics

THE FRUITS OF FREE LABOR IN THE SMALLER ISLANDS OF THE BRITISH WEST INDIES

The emancipation of an enslaved race seems, at first thought, a most uncertain and perilous undertaking. To do away with inherited and constantly strengthening tendencies toward irresponsibility and idleness,—to substitute the pleasure of activity or the distant good from industry for the very palpable influence of compulsion,—to implant forethought and alertness and ingenuity, where, before, labor was stolid and sulky and unthinking,—to confer the habit of self-dependence and the courage for unknown tasks on a people timid, childish, and dependent,—to teach self-control in place of the custom of control by masters, or by caprice and passion,—in a word, to make a free man out of a born slave,—appears at first sight the most difficult task which any legislator or reformer could ever attempt.

Leaving out of view all possible moral changes which might be induced by time and patient labor on such a being, we should say beforehand that at least economically—that is, regarding the production for the wants of the world by the freed man—the experiment of emancipation would prove, in all probability, a failure. We put it to the reader. Suppose that you, an Anglo-American, not born a slave, had by some misfortune been captured fifteen years since by an Algerine pirate, and during those years, under the fear of lash and bayonet, had been vigorously adding to the commodities of the world in the production of cotton. At length, in some moment of Algerine sentiment for human rights, you are set free by the government, and are enabled to possess a little farm of your own in the African mountains. What would probably be your views as to the economic duty of adding to that great benefaction to the human race, the production of cotton? What would be your personal sentiments toward cotton and all species of labor connected therewith? How, especially, would you be apt to view the estate where you had spent so many agreeable years, and the master for whom you had produced so much without reward? Fancy an effort on his part to hire you,—possibly even at lower wages than other laborers receive, in view of your many obligations to him!

It is barely possible that you might prefer even the small farm,—where you were producing nothing but “pumpkin” for the world, to increasing the exports of Algeria on the old property, under the same master and at half-wages. For some years at least, the world’s production would not probably be greatly assisted by you. A certain degree of idleness would have a charm for a time, even to an Anglo-American, after such an experience.

What shall we say, then, of an inferior race, slave-born, ignorant, and undisciplined by moral influences, placed suddenly in such new and strange circumstances? Could we reasonably expect that they would at once labor under freedom as they did under slavery? Could we demand that the properties which had been sprinkled with the sweat of their unrequited toil for so many years, which possibly had witnessed their sufferings under nameless wrongs, where the tone even of the now labor-paying landlord must have something of the old ring of the slave-master,—that these should be cultivated as eagerly as their own little farms by freed men? Especially could we ask it, if the masters undertook to exercise their old sway over political economy, and paid less wages than the market-rate, and even these with irregularity? Should we be rightfully shocked, if the products of these large estates even entirely failed through want of labor? What else could we expect?

Suppose, still further, as years went by, the former masters, all the wealthy and powerful classes of society, united in discouraging the improvement and opposing the general education of this, the lowest and poorest class. What would be the almost certain result?

If we should hear that such an emancipation was an economic failure, we should not be in the least surprised. If we were told that the freed men would not work on the old estates,—that the products were falling off,—that the emancipated slaves were not willing to work at all,—that they were idle, and were growing constantly more ignorant and corrupt in morals, and useless to the world,—we should sigh, but say,—“It is the natural retribution for injustice. These are the harvests of slavery.”

But if—contrary to our expectation—the results of this emancipation were entirely different: if the freed man produced more than the slave,—if he was more industrious, more active, more laborious and self-dependent,—if he even labored for his former master for hire,—if the latter confessed that the hire of the free man was cheaper than the ownership of the slave,—if tables of export and import showed that he added far more to the wealth of the world than ever before,—if the increasing price of land proved the efficiency of his industry,—if independent freeholds were created in large numbers since emancipation,—if additional churches and schools made evident the improvement of character and the desire of advancement: we should be obliged to say that there was but one explanation of this most happy and unexpected improvement, namely,—that the human soul, by virtue of its very nature and capacities, is somehow adapted to freedom, so that the most imbruted and degraded is better and more useful, when he cares and labors for himself, than when another utterly controls him.

That the negro will not work, unless he is forced to, is the strong and almost invincible objection in the minds of multitudes of persons to emancipation.

What, then, are the facts bearing on this important point? We propose, under the guidance of candid observers and travellers, such as Schomburg, Breen, Cochin, Burnley, and, best of all, Sewell, briefly to examine a field where the experiment has been fairly tried, namely, the smaller islands of the British West Indies. A full examination of the larger island, Jamaica,—would of itself demand an entire article, or even a volume.

The remark is often repeated by West Indian travellers, that no sweeping conclusions on economical points can ever be true of the West Indies as a whole,—that each island is distinct from the others, and to be judged on principles which apply to itself alone. This important fact must be borne in mind by the reader, in examining the question of the results of emancipation in the West Indies.

In Barbadoes the governing peculiarities are the dense population to the area, and the great numbers of the laboring class. The number to the square mile is greater than in China, averaging eight hundred. This fact alone placed a much greater power in the masters’ hands after emancipation, as the competition of labor must be so much more severe than with a more sparse population.

With something of the perversity induced by slavery, the planters maintained a species of land-tenure among their freed slaves which could not but have a disastrous effect.

In the first years succeeding the act of emancipation, the tenant worked for twenty per cent. below the market-rate of wages, and his service was considered equivalent to the rent. Now he possesses a house and a land-allotment on an estate for which he pays a stipulated rent; but, as a condition of renting, he must give a certain number of days’ work at certain wages, generally from one-sixth to one-third lower than the market-rate. The usual wages are twenty-four cents a day; by this system of tenancy-at-will, the freed negro in Barbadoes must labor for twenty cents.

What would be the natural results of such a system? Can we wonder at such facts as Mr. Sewell quotes from a Tobago paper, in which the writer “deplores the perverse selfishness of the laborers,” (i.e. in buying farms of their own,) and complains that “the laborers have large patches of land under cultivation, and hire help at higher wages than the estates can afford to pay,” and otherwise oppress their former benefactors? The remedy which the aggrieved correspondent suggests is the immediate importation of Coolies.

The truth is, however, that, owing to the crowded population of Barbadoes, the planters have had everything in their own hands, much more than in other islands. In Trinidad or British Guiana the negroes were not obliged by competition to submit to the obnoxious tenure; and they soon found, where land was so cheap, that a path to independence lay open before them in working their own little properties. The planters became more stubborn and more rigid, and the result was in many cases the absolute abandonment of large estates for want of labor.

The industry of the Barbadoes population is shown in the fact, that, out of the 106,000 acres of the island, 100,000 are under cultivation,1 while the average price of land rises to the unprecedented height of five hundred dollars an acre.

Notwithstanding the high price of land and the low rate of wages, the freed slaves have increased the number of small proprietors with less than five acres from 1100 to 35372 during the last fifteen years,–an increase which alone testifies to the remarkable thrift of the emancipated negro in Barbadoes.

Mr. Sewell has talked with all classes and conditions, and “none are more ready to admit than the planters that the free laborer is a better, more cheerful, and industrious workman than was ever the slave.”

“The colored mechanics and artisans of Barbadoes,” says the same author, “are equal in general intelligence to the artisans and mechanics of any part of the world equally remote from the great centres of civilization. The peasantry will soon equal them, when education is more generally diffused.”

The surest evidences, however, on this question are those of figures. Land has doubled in value on the island since emancipation.3 Of the increased value of estates, we quote, as an example, the case mentioned in a published letter of Governor Hincks, January, 1858:—

“As to the relative cost of slave and free labor in this colony, I can supply facts upon which the most implicit reliance can be placed. They have been furnished to me by the proprietor of an estate containing three hundred acres of land, and situated at a distance of about twelve miles from the shipping port. The estate referred to produced during slavery an annual average of 140 hogsheads of sugar of the present weight, and required 230 slaves. It is now worked by 90 free laborers: 60 adults, and 30 under 16 years of age. Its average product during the last seven years has been 194 hogsheads. The total cost of labor has been £770 16s., or £3 19s. 2d. per hogshead of 1,700 pounds. The average of pounds of sugar to each laborer during slavery was 1,043 pounds, and during freedom 3,660 pounds. To estimate the cost of slave-labor, the value of 230 slaves must be ascertained; and I place them at what would have been a low average,—£50 sterling each,—which would make the entire stock amount to £11,500. This, at six per cent. interest, which on such property is much too low an estimate, would give £690; cost of clothing, food, and medical attendance I estimate at £3 10s., making £805. Total cost, £1,495, or £10 12s. per hogshead, while the cost of free labor on the same estate is under £4.”

In 1853, the French committee charged by the Governor of Martinique to visit the island reported, that “in an agricultural and manufacturing point of view the aspect of Barbadoes is dazzling.”

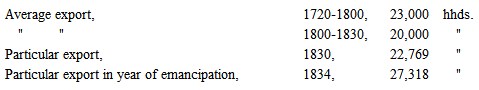

Sugar is the most important export. The following were the amounts exported before emancipation, according to Schomburg and Sewell:—

(The weight of a hogshead of sugar, it should be noted, was only 12 cwt. between 1826 and 1830; from 1830 to 1850, 14 cwt.; and now it is from 15 to 17 cwt.)

That is, an average more than double the export for ten years preceding emancipation.

Besides sugar, other articles are exported now to the value of $100,000. In addition, there is a large production for home-consumption, of such articles as sweet potatoes, eddoes, yams, cassava-root, etc.

If imports are the true expression of a nation’s economic well-being,—as all sound political economists affirm,—then can Barbadoes show most conclusively how much more profitable to a people is freedom than chatteldom.

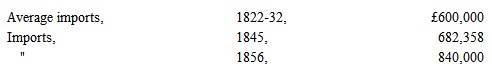

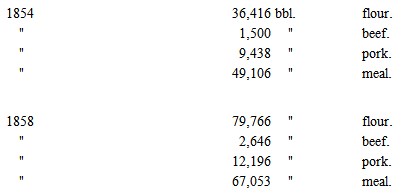

The imports from America are increasing in rapid measure. Thus they were in

Under slavery, the value of American imports was not more than £60,000 per annum. Under freedom, it is from £300,000 to £400,000.

The shipping before emancipation (in 1832) numbered 689 vessels of 79,000 tons. In 1856, 966 vessels of 114,800 tons.

The population of Barbadoes is supposed to be now about 140,000, of whom 124,000 are blacks. Of these, only 22,000 are believed to be field laborers, against 81,000, just before emancipation, of men, women, and children, who labored in the field,—a fact which shows the aversion slavery had implanted to laboring on the soil, as well as the indiscreet policy of the planters. Yet, despite this decrease of the most profitable kind of labor, so great is the advantage of freedom over slavery, that the island has been enabled to make this prodigious increase in production and wealth since emancipation,—more than doubling its export of sugar, increasing its imports by $1,200,000, quintupling its imports from America, and doubling the value of land.

The progress in education and morality has not been at all so rapid as in wealth. The freed slave could not at once escape from the debasing influences of years of bondage, and the planters have deliberately set themselves against any system of popular education. Crimes against property, Sewell says, are rife, especially thieving; petty acts of anger and cruelty are also common, as well as offences against chastity; while, on the other hand, crimes of violence are almost unknown. From the last census it appears that more than half of the children born in the island are illegitimate. This sad condition of morals Mr. Sewell attributes principally to the imperfect education of the lowest classes,—the schools being mostly church-schools, and somewhat expensive. These schools, however, have increased from 27 in 1834, with 1,574 children, to 70 with 6,180 in 1857, and an infant school with 1,140; the children in Sunday-schools have increased in the same time from 1,679 to 2,071.4

St. Vincent is generally considered by the passing traveller as another example of the axiom that “the freed negro will not work,” and of “the melancholy fruits of emancipation.”

The decline of the wealthier classes began before emancipation, and continued after it. The planters were deeply in debt, and their estates heavily mortgaged. Slavery there, as everywhere, wasted the means of the masters, and exhausted the soil. When the day of freedom came, these gentlemen, instead of prudently endeavoring to retain the laborers on their estates, offered them lower wages than were paid on the neighboring islands. The consequence was, that the negroes preferred to buy their own little properties or to hire farms in the interior, and let the great estates find labor as they could. Mr. Sewell states that he inquired much in regard to the abandoned sugar-estates, and never found one which was deserted because labor could not be procured at fair cost; the more general reason of their abandonment was want of capital, or debt incurred previously to emancipation. That the condition of the island is not caused by the idleness of the negro is shown by the facts, that since emancipation houses have been built by freed slaves for themselves and their families, containing 8,209 persons; that from 10,000 to 12,000 acres have been brought under cultivation by the proprietors of small properties of from one to five acres; that the export of arrowroot (which is one of the small articles raised by the negroes on their own grounds) has risen from 60,000 pounds before emancipation to 1,352,250 pounds in 1857, valued at $750,000, and the cocoa-nut export has also increased largely.

The export of sugar has declined as follows:—Under slavery, (1831-34,) it was 204,095 cwt.; under apprenticeship, (1835-38,) 194,228; under free labor, (1839-45,) 127,364 cwt.; in 1846, 129,870 cwt.; in 1847, 175,615 cwt.5

The moral condition of the island seems most favorable. In a population of 30,000, there are no paupers, and 8,000 is the average church-attendance, while the average school-attendance is 2,000. The criminal records show a remarkable obedience to law; there being only seven convictions in 1857 for assault, six for felony, and 162 for minor offences. The proportion under slavery was far greater.

Grenada presented clear evidences of decline long before emancipation. The slave-population decreased as follows:—

this last number being that for which compensation was made. The total value of all the exports in 1776 was about $3,000,000; in 1823, less than $2,000,000; in 1831, a little over $1,000,000.

The sugar export declined from 24,000,000 pounds in 1776 to 19,000,000 pounds in 1831: or more exactly, under slavery, (1831-34,) it was 193,156 cwt.; during apprenticeship, 161,308 cwt.; under free labor, (1839-45,) 87,161 cwt.; in 1846, 76,931 cwt.; in 1847, 104,952 cwt.: showing in the last year a considerable increase.

The policy of the Grenadian planters in offering low wages—the rate being from 5s. to 5s. 6d. a week—has driven the negroes to their own little properties, and has caused a diminution in the production of sugar on the large organized estates. Yet the production of other smaller articles has greatly increased, and the general well-being of the people is much advanced.

Before 1830 there were no small freeholders; now there are over 2,000. Nearly 7,000 persons live in villages, built since emancipation, and 4,573 pay direct taxes.

Last year there were only 60 paupers on the island, and those were aged and sick persons; only 18 were convicted of felony, 6 of theft, and 2 of other offences. There is an average church-attendance of 8,000, and a school-attendance of 1,600. In 1857, out of 80,000 acres, 43,800 were in a state of cultivation, and 3,800 acres were added to the cultivation of the previous year.

The sugar export of 1857 was only half that of 1831, while the aggregate value of all the exports had risen from £153,175 to £218,352. The imports had risen in the same time from £77,000 to £109,000.6

Tobago also showed a gradual decline before emancipation; and since that event, the production of sugar has fallen off as follows: In 1831-34 it was 99,579 cwt.; 1835-38, 89,332 cwt.; 1839-1845, 52,962 cwt.; 1846, 38,882 cwt.; 1847, 69,240 cwt. One great cause of this decline is the drawing off of capital from the old, worn-out lands to the fresh, rich, and profitable culture of Trinidad, where land is very cheap. Moreover, the climate of Tobago is not entirely favorable to sugar.

Yet a great improvement is manifest among the people. Small proprietors have much increased; even the field-hands now possess houses and lands of their own. There are 2,500 freeholders, and 2,800 tax-payers. The average church-attendance is 41 per cent, of the whole population; the average school-attendance, 1,600. Commerce is rapidly advancing. The imports have risen from £50,307 in 1854 to £59,994 in 1856; and the exports from £49,754 to £79,789 in the same time.

In St. Lucia the planters have followed a more wise and liberal policy towards the emancipated slaves. Better wages have been offered; liberal inducements have been held out to the negroes to cultivate the estates; efforts have been put forth to improve the social and moral condition of the laboring class. Tenancy-at-will is unknown, and the mélairie system (laboring on shares) has been introduced. In other words, the rich and educated have manifested some kind of humane interest for the laborers, and in return the latter have worked well and cheerfully.

Yet, in St. Lucia, as in so many other West India colonies, the financial condition of the planters, at the time of emancipation, was exceedingly embarrassed: their registered debts amounting in 1829, according to Breen, to £1,189,965.

The export of sugar is stated in Cochin’s carefully prepared tables as follows: In the period of slavery, (1831-34,) 57,549 cwt.; during the apprenticeship, (1835-38,) 51,427 cwt.; under free labor, (1839-45,) 57,070 cwt; in 1846, 63,566 cwt.; in 1847, 88,370 cwt.

The imports have not risen till recently, and indicate a greater consumption of articles grown on the island. In 1833,7 they were in value, £108,076; in 1840, £114,537; in 1843, £70,340; in 1851,8 £68,881; in 1857, £90,064.

Of the total value of exports Breen gives tables only to 1843. In that year, they were £96,290 against £71,580 in 1833.

Since emancipation, 2,045 of the negroes have become freeholders, and 4,603 pay direct taxes.

In Trinidad, the question of the effects of emancipation has some peculiar elements. The island is a very large, fertile country, with a sparse population, where of course land is cheap and labor dear. Out of its 1,287,000 acres,9 only some 30,000 are cultivated. Its whole population is but about 80,000, of whom the colored number near 50,000. Emancipation would work upon such a country somewhat as it might on Texas, for instance. There were 11,000 field-hands on the estates when slavery was abolished. The planters undertook to maintain or introduce the tenancy-at-will system, and to reduce the wages below the market-rate. Whenever the negroes retired from the estate-work, they were summarily ejected from their houses and lands, and their little gardens were destroyed. The natural effect of such an injudicious policy was, that the negro preferred squatting on the government lands about him, or buying a small, cheap plot, or hiring a farm, to remaining under the planters, and soon some 7,000 laborers had left the estates.

Many associated the idea of servitude with labor in the fields, and, abandoning agriculture, took to trade in the towns and villages, which they still pursue. Some 4,000 remained on the estates, and have never progressed, like their more independent brethren. The criminal records show a greater proportion of crime among them than among any other class. Of the others, five-sixths became proprietors of farms from one to five acres each, and 4,500 hire themselves occasionally to the estates every year.

One effect of the unfortunate contentions between capital and labor in the island has been, that no general system of public instruction was introduced till recently; education was entirely neglected: though now, under the new system, the people will receive much more general instruction, for which purpose $20,000 were appropriated in 1859.

The public morality under such circumstances is of course of a low order. Out of 136 children born in Port-of-Spain, 100 were illegitimate. The convictions in the island for felony were 63; for misdemeanor, 865; for debt, 230.

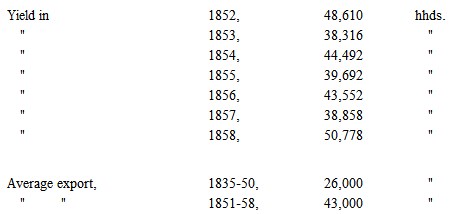

The records of material progress show a much better result. The sugar cultivation in the last twenty years has nearly doubled, and the land in cane has risen from 15,000 to 29,000 acres. The production of cocoa has increased, though in a less proportion; while the production and consumption of home necessaries and luxuries have immensely advanced. Great practical improvements are being made everywhere, such as the substitution of steam-power for cattle and water-power. The export of sugar,10 especially since the introduction of Coolie labor, has advanced rapidly. Before emancipation the highest export was 30,000 hhds., equal to 24,000 hhds. at present weight. Late export,—