полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 395, October 24, 1829

At St. Helier a stranger may, without any great stretch of imagination, fancy himself in England; but no sooner does he penetrate into the country, than such self-deception becomes impossible. The roads, even the best of them, are mere paths, narrow, deep sunk between enormous dikes, and so fenced by hedges and trees, as to be almost impervious to the light of day. The fields, of which it is scarce possible to obtain a glimpse from these "covered ways," are paltry paddocks, rarely exceeding two or three acres. Hedges and orchards render the face of the country like a forest, and nearly as much ground is occupied by lanes and fences as is under the plough.

(To be concluded in our next.)

SPIRIT OF THE Public Journals

THE IDIOT.—AN ANECDOTEEvery reader of dramatic history has heard of Garrick's contest with Madam Clairon, and the triumph which the English Roscius achieved over the Siddons of the French stage, by his representation of the father struck with fatuity on beholding his only infant child dashed to pieces by leaping in its joy from his arms: perhaps the sole remaining conquest for histrionic tragedy is somewhere in the unexplored regions of the mind, below the ordinary understanding, amidst the gradations of idiotcy. The various shades and degrees of sense and sensibility which lie there unknown, Genius, in some gifted moment, may discover. In the meantime, as a small specimen of its undivulged dramatic treasures, we submit to our readers the following little anecdote:—

A poor widow, in a small town in the north of England, kept a booth or stall of apples and sweetmeats. She had an idiot child, so utterly helpless and dependent, that he did not appear to be ever alive to anger or self-defence.

He sat all day at her feet, and seemed to be possessed of no other sentiment of the human kind than confidence in his mother's love, and a dread of the schoolboys, by whom he was often annoyed. His whole occupation, as he sat on the ground, was in swinging backwards and forwards, singing "pal-lal" in a low pathetic voice, only interrupted at intervals on the appearance of any of his tormentors, when he clung to his mother in alarm.

From morning to evening he sang his plaintive and aimless ditty; at night, when his poor mother gathered up her little wares to return home, so deplorable did his defects appear, that while she carried her table on her head, her stock of little merchandize in her lap, and her stool in one hand, she was obliged to lead him by the other. Ever and anon as any of the schoolboys appeared in view, the harmless thing clung close to her, and hid his face in her bosom for protection.

A human creature so far below the standard of humanity was no where ever seen; he had not even the shallow cunning which is often found among these unfinished beings; and his simplicity could not even be measured by the standard we would apply to the capacity of a lamb. Yet it had a feeling rarely manifested even in the affectionate dog, and a knowledge never shown by any mere animal.

He was sensible of his mother's kindness, and how much he owed to her care. At night when she spread his humble pallet, though he knew not prayer, nor could comprehend the solemnities of worship, he prostrated himself at her feet, and as he kissed them, mumbled a kind of mental orison, as if in fond and holy devotion. In the morning, before she went abroad to resume her station in the market-place, he peeped anxiously out to reconnoitre the street, and as often as he saw any of the schoolboys in the way, he held her firmly back, and sang his sorrowful "pal-lal."

One day the poor woman and her idiot boy were missed from the market-place, and the charity of some of the neighbours induced them to visit her hovel. They found her dead on her sorry couch, and the boy sitting beside her, holding her hand, swinging and singing his pitiful lay more sorrowfully than he had ever done before. He could not speak, but only utter a brutish gabble! sometimes, however, he looked as if he comprehended something of what was said. On this occasion, when the neighbours spoke to him, he looked up with the tear in his eye, and clasping the cold hand more tenderly, sank the strain of his mournful "pal-lal" into a softer and sadder key.

The spectators, deeply affected, raised him from the body, and he surrendered his hold of the earthy hand without resistance, retiring in silence to an obscure corner of the room. One of them, looking towards the others, said to them, "Poor wretch! what shall we do with him?" At that moment he resumed his chant, and lifting two handfuls of dust from the floor, sprinkled it on his head, and sang with a wild and clear heart-piercing pathos, "pal-lal—pal-lal."—Blackwood's Magazine.

ENGLISH HEADSComparative estimate respecting the dimensions of the head of the inhabitants in several counties of England.

The male head in England, at maturity, averages from 6-1/2 to 7-5/8 in diameter; the medium and most general size being 7 inches. The female head is smaller, varying from 6-3/8 to 7, or 7-1/2, the medium male size. Fixing the medium of the English head at 7 inches, there can be no difficulty in distinguishing the portions of society above from those below that measurement.

London.—The majority of the higher classes are above the medium, while amongst the lower it is very rare to find a large head. Spitalfields Weavers have extremely small heads, 6-1/2, 6-5/8, 6-3/4, being the prevailing admeasurement.

Coventry.—Almost exclusively peopled by weavers, the same facts are peculiarly observed.

Hertfordshire, Essex, Suffolk, and Norfolk, contain a larger proportion of small heads than any part of the empire; Essex and Hertfordshire, particularly. Seven inches in diameter is here, as in Spitalfields and Coventry, quite unusual—6-5/8 and 6-1/2 are more general; and 6-3/8, the usual size for a boy of six years of age, is frequently to be met with here in the full maturity of manhood.

Kent, Surrey, and Sussex.—An increase of size of the usual average is observed; and the inland counties, in general, are nearly upon the same scale.

Devonshire and Cornwall.—The heads of full sizes.

Herefordshire.—Superior to the London average.

Lancashire, Yorkshire, Cumberland, and Northumberland, have more large heads, in proportion, than any part of the country.

Scotland.—The full-sized head is known to be possessed by the inhabitants; their measurement ranging between 7-3/4 and 7-7/8 even to 8 inches; this extreme size, however, is rare.—Literary Gazette.

The Naturalist

ZOOLOGICAL GARDENSThe laying-out of the tract of ground on the northern verge of the Regent's Park, and divided from the present garden of the Zoological Society, has at length been commenced, and is proceeding with great activity. We described this as part of the gardens in our illustrated account of them in No. 330 of the MIRROR, and we now congratulate the Society on their increased funds which have enabled them to begin this very important portion of their original design.

For the purposes of these alterations, the belt of trees and shrubs which formed so complete and natural a barrier between the road and canal, will be removed; but when the buildings, &c. are completed, trees and shrubs are to be replanted close to the road. In addition to huts, cages, &c. for the reception of living animals, it is said that a building will be erected in the new garden for the whole or part of the Society's Museum, now deposited in Bruton Street. This is very desirable, as the Establishment will then combine similar advantages to those of the Jardin des Plantes at Paris, where the Museum is in the grounds. The addition of a botanical garden would then complete the scheme, and it is reasonable to hope that some of the useless ground in the park may be applied to this very serviceable as well as ornamental purpose.

The communication between the present Zoological exhibition, and the additions in preparation, will be by a vaulted passage beneath the road. This subterranean passage will be useful for the abode of such portions of varied creation as love the shade, as bats, owls, &c.

THE GIRAFFEThe King's Giraffe died on Sunday week, at the Menagerie at Sandpit-gate, near Windsor. It was nearly four years and a half old, and arrived in England in August, 1827, as a present from the Pacha of Egypt to his Majesty.

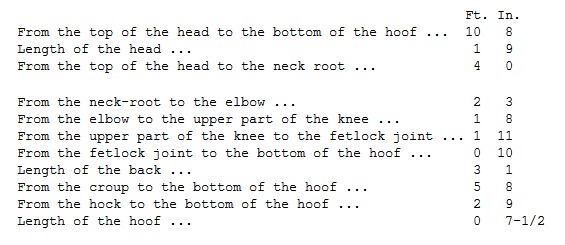

About the same time another Giraffe arrived at Marseilles, being also a present from the Pacha to the King of France. This and the deceased animal were females, and were taken very young by some Arabs, who fed them with milk. The Governor of Sennaar, a large town of Nubia, obtained them from the Arabs, and forwarded them to the Pacha of Egypt. This ruler determined on presenting them to the Kings of England and France; and as there was some difference in size, the Consuls of each nation drew lots for them. The shortest and weakest fell to the lot of England. The Giraffe destined for our Sovereign was conveyed to Malta, under the charge of two Arabs; and was from thence forwarded to London, in the Penelope merchant vessel, and arrived on the 11th of August. The animal was conveyed to Windsor two days after, in a spacious caravan. The following were its dimensions, as measured shortly after its arrival at Windsor:

From the period of its arrival to June last, the animal grew 18 inches. Her usual food was barley, oats, split beans, and ash-leaves: she drank milk. Her health was not good; her joints appeared to shoot over, and she was very weak and crippled. She was occasionally led for exercise round her paddock, when she was well enough, but she was seldom on her legs: indeed, so great was the weakness of her fore legs for some time previous to her death, that a pulley was constructed, being suspended from the ceiling of her hovel, and fastened round her body, so as to raise her on her legs without any exertion on her part. When she first arrived she was exceedingly playful, and up to her death continued perfectly harmless.—Abridged from the library of Entertaining Knowledge.

The Anecdote Gallery

YOUTH AND GENIUS OF MOZART(Concluded from page 256.)

On the 10th of April, 1764, the family arrived in England, and remained there until the middle of the following year. Leopold Mozart fell ill of a dangerous sore throat during his stay, and as no practising could go forward in the house at that time, his son employed himself in writing his first sinfonia. It was scored with all the instruments, not omitting drums and trumpets. His sister sat near him while he wrote, and he said to her, "remind me that I give the horns something good to do." An extract or two from the correspondence of the father will show how they were received in England:—

"A week after, as we were walking in St. James's Park, the king and queen came by in their carriage, and, although we were differently dressed, they knew us, and not only that, but the king opened the window, and, putting his head out and laughing, greeted us with head and hands, particularly our Master Wolfgang."

"On the 19th of May, we were with their Majesties from six to ten o'clock in the evening. No one was present but the two princes, brothers to the king and queen. The king placed before Wolfgang not only pieces of Wagenseil, but of Bach, Abel, and Handel, all of which he performed prima vista. He played upon the king's organ in such a style that every one admired his organ even more than his harpsichord performance. He then accompanied the queen, who sang an air, and afterwards a flute-player in a solo. At last they gave him the bass part of one of Handel's airs, to which he composed so beautifal a melody that all present were lost in astonishment. In a word, what he knew in Salzburg was a mere shadow of his present knowledge; his invention and fancy gain strength every day."

"A concert was lately given at Ranelagh for the benefit of a newly erected Lying-in-Hospital. I allowed Wolfgang to play a concerto on the organ at it. Observe—this is the way to get the love of these people."

A large portion of Leopold Mozart's letters is occupied with masses to be offered up for the health, &c.; and during his sojourn in the Five-fields, Chelsea, he appears to have been in considerable hope that he had converted a Mr. Sipruntini (a Dutch Jew, and a fine violoncello player), to Catholicism. After dedicating a set of sonatas to the queen, and experiencing great patronage from the nobility, Mozart, with his father and sister, in July, 1765, crossed over into the Netherlands. At the Hague, a fever attacked both children, and had nearly cost the daughter her life. On their recovery, they played before the Prince of Orange, and Wolfgang composed some variations on a national air, which was, just then, sung, piped, and whistled throughout the streets of Holland. The organist of the cathedral in Haerlem waited upon the Mozarts, and invited the son to try his instrument, which he did the next morning. Mozart senior describes the organ as a magnificent one, of sixty-eight stops, and built wholly of metal, "as wood would not endure the dampness of the Dutch atmosphere." Upon the return of the family to Salzburg, Mozart enjoyed a year of quiet and uninterrupted study in the higher walks of composition. Besides applying to the old masters, he was indefatigable in perusing the works of Emanuel Bach, Hasse, Handel, and Eberlin, and by the diligent performance of these authors, he acquired extraordinary brilliancy and power in the left hand. On the 11th of September, 1767, the whole family proceeded on their way to Vienna; but as the small pox was raging there, they went to Ollmütz instead, where both the children caught that disorder. At Vienna, Mozart wrote his first opera, by desire of the emperor. Though the singers extolled their parts to the skies, in presence of Leopold Mozart, they formed in secret a cabal against the work, and it was never performed. The Italian singers and composers who were established in this capital did not like to find themselves surpassed in knowledge and skill by a boy of twelve years old, and they therefore not only charged the composition with a want of dramatic effect, but they even went so far as to say, that he had not scored it himself. To counteract such calumnies, Leopold Mozart often obliged his son to put the orchestral parts to his compositions in the presence of spectators, which he did with wonderful celerity before Metastasio, Hasse, the Duke of Braganza, and others. The injurious opinion of the nobility, which these people hoped to excite against the young musician, had no success; for he composed a Mass—an Offertorium—and a Trumpet Concerto for a Boy—which were performed before the whole court, and at which he himself presided and beat the time. The year 1769 was employed by Wolfgang in studying the Italian language, and in the practice of composition; and at this time he was appointed concert master to the court of Salzburg.

Father and son now made the tour of Italy, and met in every city with an enthusiastic reception.

In Rome, Mozart gave a miraculous attestation of his quickness of ear, and extensive memory, by bringing away from the Sistine Chapel the "Miserere of Allegri," a work full of imitation and repercussion, mostly for a double choir, and continually changing in the combination and relation of the parts. This accomplished piece of thievery was thus performed:—the sketch was drawn out upon the first hearing, and filled up from recollection at home—Mozart then repaired to the second and last performance, with his manuscript in his hat, and corrected it.

The slow voluptuous movement of the style of dancing prevalent in Italy gave Mozart great pleasure; in the postscripts to his father's letters, which he generally addressed to his sister and playfellow, he speaks of this subject with as much zest as of his own art. Later in manhood he became a pupil of Vestris, and the gracefulness of his dancing was much admired, especially in the minuet.

About this time Mozart's voice began to break, and he ceased to sing in public, unless words were put before him; the violin he continued to play, but mostly in private. The alarming illnesses which had attacked his children on their journey kept Leopold Mozart in continual anxiety—the malaria of Rome and the heat of Naples were alike dreaded by him.

The travellers arrived at Naples in May, and fortunately procured cool and healthy lodgings. Here they visited the English Ambassador, Sir William Hamilton, whose acquaintance they had made in London, and whose lady was not only a very agreeable person, but a charming performer on the harpsichord. She trembled on playing before Mozart. The concerts given by the Mozarts in Naples were very successful, and they were treated with great distinction; the carriages of the nobility, attended by footmen with flambeaux, fetched them from home and carried them back; the queen greeted them daily on the promenade, and they received invitations to the ball given by the French Ambassador on the marriage of the Dauphin.

If Mozart had not been engaged to compose the carnival opera for Milan, he might have written that for Bologna, Rome, or Naples, as at these three cities offers were made to him, a proof of what his genius had effected in Italy.

The epoch at which Mozart's genius was ripe may be dated from his twentieth year; constant study and practice had given him ease in composition, and ideas came thicker with his early manhood—the fire, the melodiousness, the boldness of harmony, the inexhaustible invention which characterize his works, were at this time apparent; he began to think in a manner entirely independent, and to perform what he had promised as a regenerator of the musical art. The situation of his father as Kapell-meister, in Salzburg, indeed gave Mozart some opportunities of writing church music, but not such as he most coveted, the sacred musical services of the court being restricted to a given duration, and the orchestra but poorly supplied with singers; it was therefore his earnest desire to get some permanent appointment in which he could exercise freely his talent for composition, and reckon on a sufficient income. When childhood and boyhood had passed away, his quondam patrons ceased to wonder at, or feel interest in, his genius, and Mozart, whose early years had been spent in familiar intercourse with the principal nobility of Europe, who had been from court to court, and received distinctions and caresses unparalleled in the history of musicians, up to the period of his death gained no situation worthy his acceptance, but earned his fame in the midst of worldly cares and annoyances, in alternate abundance and poverty, deceived by pretended friendship, or persecuted by open enmity. The obstacles which Mozart surmounted in establishing the immortality of his muse, leave those without excuse who plead other occupations and the necessity of gaining a livelihood as an excuse for want of success in the art. Where the creative faculty has been bestowed, it will not be repressed by circumstances.

In the exterior of Mozart there was nothing remarkable; he was small in person, and had a very agreeable countenance, but it did not discover the greatness of his genius at the first glance. His eyes were tolerably large and well shaped, more heavy than fiery in the expression; when he was thin they were rather prominent. His sight was always quick and strong; he had an unsteady abstracted look, except when seated at the piano-forte, when the whole form of his visage was changed. His hands were small and beautiful, and he used them so softly and naturally upon the piano-forte, that the eye was no less delighted than the ear. It was surprising that he could grasp so much as he did in the bass. His head was too large in proportion to his body, but his hands and feet were in perfect symmetry, of which he was rather vain. The stunted growth of Mozart's body may have arisen from the early efforts of his mind; not, as some suppose, from want of exercise in childhood—for then he had much exercise—though at a later period the want of it may have been hurtful to him. Sophia, a sister-in-law of Mozart, who is still living, relates: "he was always good-humoured, but very abstracted, and in answering questions seemed always to be thinking of something else. Even in the morning when he washed his hands, he never stood still, but would walk up and down the room, sometimes striking one heel against the other; at dinner he would frequently make the ends of his napkin fast, and draw it backwards and forwards under his nose, seeming lost in meditation, and not in the least aware of what he did." He was fond of animals, and in his amusements delighted with any thing new; at one time of his life with riding, at another with billiards.

The Selector; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

A PORTRAIT, BY MISS LANDONFROM "THE VENETIAN BRACELET, AND OTHER POEMS," (JUST PUBLISHED)"O No, sweet Lady, not to theeThat set and chilling tone,By which the feelings on themselvesSo utterly are thrown,For mine has sprung upon my lips,Impatient to expressThe haunting charm of thy sweet voiceAnd gentlest loveliness.A very fairy queen thou art,Whose only spells are on the heart.The garden it has many a flower,But only one for thee—The early graced of Grecian song,The fragant myrtle tree;For it doth speak of happy love,The delicate, the true.If its pearl buds are fair like thee,They seem as fragile too;Likeness, not omens; for love's powerWill watch his own most precious flower.Thou art not of that wilder raceUpon the mountain side,Able alike the summer sunAnd winter blast to bide;But thou art of that gentle growthWhich asks some loving eyeTo keep it in sweet guardianship,Or it must droop and die;Requiring equal love and care,Even more delicate than fair.I cannot paint to thee the charmWhich thou hast wrought on me;Thy laugh, so like the wild bird's songIn the first bloom-touch'd tree.You spoke of lovely Italy,And of its thousand flowers;Your lips had caught the music breathAmid its summer bow'rs.And can it be a form like thineHas braved the stormy Apennine?I'm standing now with one white roseWhere silver waters glideI've flung that white rose on the stream—How light it breasts the tide!The clear waves seem as if they lovedSo beautiful a thing;And fondly to the scented leavesThe laughing sunbeams cling.A summer voyage—fairy freight;—And such, sweet Lady, be thy fate!"WATERLOOThree volumes of tales and sketches of considerable graphic interest, have lately been published under the title of "Stories of Waterloo." The first inquiry will naturally be whether they throw any new lights on the ever-memorable struggle. The details of the day are vividly sketched, and as they must be familiar to all our readers, the following excellent general observations will be appreciated:—

"No situation could be more trying to the unyielding courage of the British army than their disposition in square at Waterloo. There is an excited feeling in an attacking body that stimulates the coldest, and blunts the thought of danger. The tumultuous enthusiasm of the assault spreads from man to man, and duller spirits catch a gallant frenzy from the brave around them. But the enduring and devoted courage which pervaded the British squares, when, hour after hour, mowed down by a murderous artillery, and wearied by furious and frequent onsets of lancers and cuirassiers; when the constant order—'Close up!—close up!' marked the quick succession of slaughter that thinned their diminished ranks; and when the day wore later, when the remnants of two, and even three regiments were necessary to complete the square which one of them had formed in the morning—to support this with firmness, and 'feed death,' inactive and unmoved, exhibited that calm and desperate bravery which elicited the admiration of Napoleon himself.

"There was a terrible sameness in the battle of the 18th of June, which distinguishes it in the history of modern slaughter. Although designated by Napoleon 'a day of false manoeuvres,' in reality there was less display of military tactics at Waterloo than in any general action we have on record. Buonaparte's favourite plan was perseveringly followed. To turn a wing, or separate a position, was his customary system. Both were tried at Hougomont to turn the right, and at La Haye Sainte to break through the left centre. Hence the French operations were confined to fierce and incessant onsets with masses of cavalry and infantry, generally supported by a numerous and destructive artillery.