полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 327, August 16, 1828

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 12, No. 327, August 16, 1828

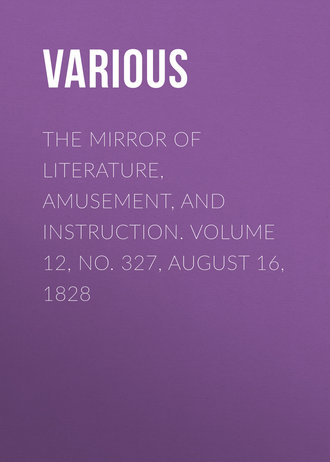

ROSAMOND'S WELL AND LABYRINTH

Rosamond's Well and Labyrinth at Woodstock.

For the originals of the annexed engravings we are indebted to the sketchbooks of two esteemed correspondents.1 The sites are so consecrated, or we should rather say perpetuated, in history, and the fates and fortunes of Rosamond Clifford are so familiar to our readers, that we shall add but few words on the locality of the Well and Bower. Their existence is thus attested by Drayton, the poet, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth:—"Rosamond's Labyrinth, whose ruins, together with her Well, being paved with square stones in the bottom, and also her Tower, from which the Labyrinth did run, are yet remaining, being vaults arched and walled with stone and brick, almost inextricably wound within one another, by which, if at any time her lodging were laid about by the queen, she might easily avoid peril imminent, and, if need be, by secret issues, take the air abroad, many furlongs about Woodstock, in Oxfordfordshire."

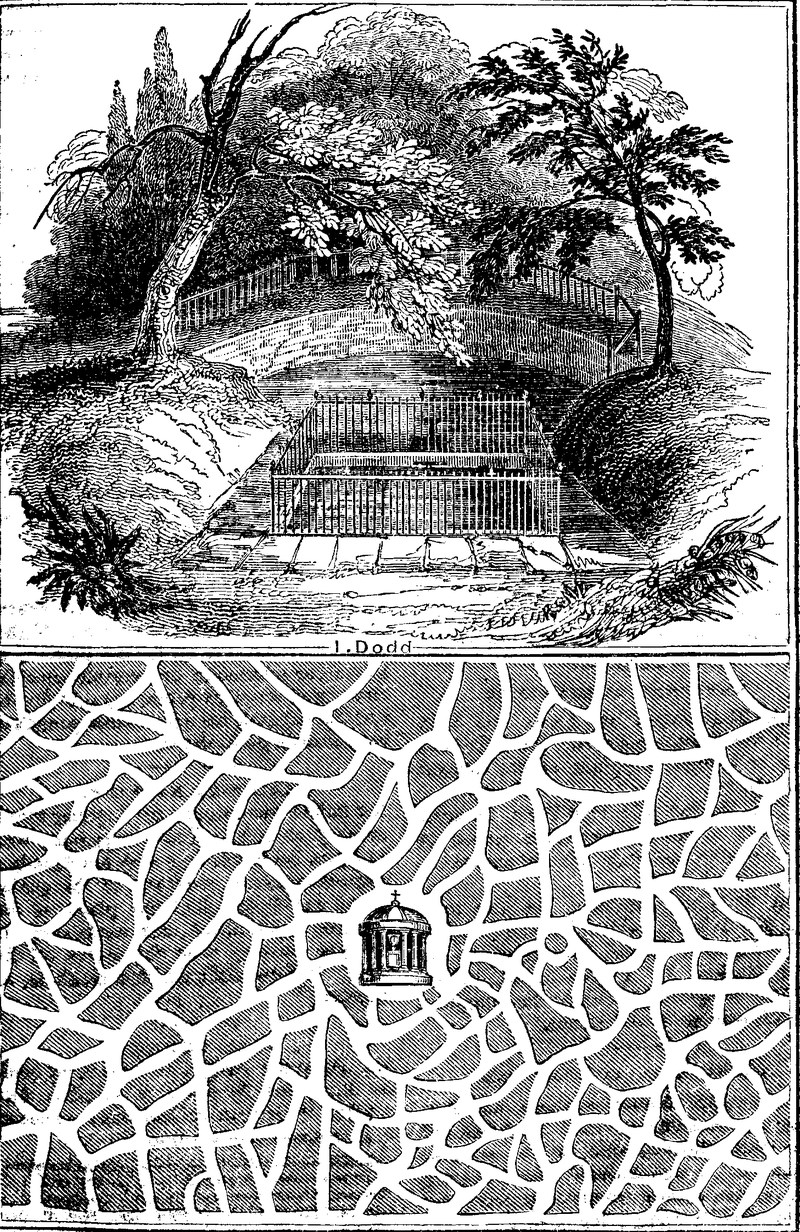

Sir Walter Scott (of whom, as of Goldsmith, it may hereafter be said, he "left no species of writing untouched or unadorned by his pen") has resuscitated the interest attached to this spot, in his masterly novel of Woodstock.2 It is here that the beautiful Alice meets the facetious Charles in his disguise of an old woman; and on the bank over the Well is the spot where tradition relates fair Rosamond yielded to the menaces of Eleanor. Our correspondent, T.W., jocosely observes, that he sends us the Labyrinth "without the silken cord which guided the cruel Eleanor to her rival, in the hope that the ingenuity of the reader will be sufficient to serve him in its stead. Observe," continues he, "the maze is entered at one of the side gates, and the bower must be reached without any of the barriers (—) being passed over—that is, by an uninterrupted pathway."3

The bower consists of fine tall trees, whose branches hang entwined over the front of the well. The spring is contained in a large basin, formed by a plain stone wall, which serves as a facing and support to the bank; the water flows from hence through a hole of about five inches in diameter, and is conveyed by a channel under the pavement into another basin of considerable dimensions, fenced with an iron railing. Hence it again escapes by means of a grating into the beautiful lake of Woodstock Park, or, as it is more modernly termed, Blenheim.

In these days of "hobgoblin lore," it may not be incurious to add, that Woodstock is distinguished in Dr. Plot's History of Oxfordshire (the title of which is well known to all readers of the marvellous) as the scene of a series of hoax and disturbance played off upon the commissioners of the Long Parliament, who were sent down to dispark and destroy Woodstock, after the death of Charles I.; and Sir Walter Scott thinks it "highly probable" that this "piece of phantasmagoria was conducted by means of the secret passages and recesses in the Labyrinth of Rosamond"—it must be admitted, a very convenient scene for such a farce. Sir Walter says, "I have not the book at hand"—neither have we; but we may probably allude to this curious affair on some future occasion. In the meantime, if our present reference should kindle the curiosity of the reader, and he may not be disposed to await our time, we beg to recommend him to Glanville's well-known work on witchcraft, which not only contains Dr. Plot's narrative of the Woodstock disturbances, but a multitude of argument for all who are sceptical of this and similar mysteries. This is an age of inquiry, and we do not see why such follies should be left unturned—from Priam's shade to the murderous dreams and omens of our own times.

THE "NAPOLEON" CHILD

On Friday the 8th inst. we paid a visit to the Bazaar in Oxford-street, to witness this extraordinary sport of Nature, about which the French and English newspapers have lately been so communicative.

The child is an engaging little girl, about three years old. The colour of her eyes is pale blue, and on the iris, or circle round their pupils, the inscriptions on

Left Eye.

NAPOLEON

EMPEREUR.

Right Eye.

EMPEREUR.

NAPOLEON.

may be traced in the above sized letters, although all the letters are not equally visible, the commencement "NAP" and "EMP" being the most distinct. The colour of the letters is almost white, and at first sight of the child they appear like rays, which make the eyes appear vivacious and sparkling. The accuracy of the inscriptions is much assisted by the stillness of the eye, on its being directed upwards, as to an object on the ceiling of the room, &c.; and with this aid the several letters may be traced with the naked eye.

This effect is accounted for by the child's mother earnestly looking at a franc-piece of Napoleon's, which was given to her by her brother previous to a long absence; and this operating during her pregnancy, has produced the appearance in question. It was visible at the child's birth, and has increased with her growth. She has been seen by Sir Astley Cooper and other leading members of the profession, and probably before our Number is published, she will have been shown to the King. She is an interesting little creature, prattles playfully, and will doubtless receive the caresses of thousands of visitors.

Our contemporaries are, we perceive, somewhat divided as to the distinctness of the inscription; but we have given our opinion fairly—and, as the proverb runs, "seeing is believing." One of them describes the child as "a little boy, about two years old." This reminds us of the man in the Critic, "give these fellows a good thing, and they never know when to have done with it."

PORTUGUESE PRISONS

(For the Mirror.)Most of the Portuguese prisons are horrible in the extreme; and it is utterly impossible for the most hardy individuals, who have the misfortune to be long confined within them, to preserve their health from ruin.

The famous prison of the Limoeiro, at Lisbon, is a dreadful place of durance. It is situated on one of the mountainous streets in the Portuguese metropolis, and was formerly the archbishop's palace. A vast proportion of the crimes committed in the city are plotted between the persons confined within, and those without, the prison; for there is nothing to prevent constant communication with the street through the double iron-bars, so that an unchecked and unobserved intercourse is maintained, much to the furtherance of crime. Through these bars all sorts of food, liquors, raiment, weapons, &c. can be conveyed from the street; and, indeed, through these bars the meals of the prisoners are served. The prison is capable of containing about 700 people; the usual number, however, is 400. The state of the apartments in which the criminals pass their time is truly distressing. The stench is overpowering; and though visitors remain in the rooms only a few minutes, they often retire seriously indisposed. The expense of maintaining the prisoners is 8,000 cruzados, or about 1,000l. per annum. Of this sum, one-half is paid by the city, and the other by the Misericordia, a benevolent association, possessing large funds from various bequeathed estates. Nevertheless, the food appears insufficient; it consists chiefly of a soup made of rice. The allowance of bread is one pound and a half per day for four persons.

G.W.N.

ADDRESSED TO MISS STREET

(For the Mirror.)In London's variegated streetsThe eye, whatever pleases, meets;For like another Street, I know,Those Streets each day more charming grow.As if by magic's changeful wand,Taste, beauty, order, strength combine;And shew a mighty master's handIn every graceful curve and line.But meaner temples strive in vainPerfection's envied height to gain;For in our matchless Street alone,The charm of perfect beauty's known.How blest, if at that living shrine,With deepest feeling, warm and true,The nameless happiness were mine,To bend in form—and spirit too.But no—though in my ardent breast,The fires of love must ever rise,Th' adverse circles of my fate,Forbid the outward sacrifice.My spirit breathes its inmost breath,In this my first—my last confession:—The passion will survive till death,But never more can know expression.W.

CHILDE'S TOMB

(For the Mirror.)From "time out of mind" a tradition has existed in Dartmoor, Devon, and is noticed by several writers, that one John Childe, of Plymstock, a gentleman of large possessions, and a noted hunter, whilst enjoying that sport during a very inclement season, was benighted, lost his way, and perished through cold and fear, in the south quarter of the forest, near Fox-tor, after taking the precaution to kill his horse, (which he much valued), as a last resource, and for the sake of warmth and prolonging life, to creep into its bowels, leaving a paper, denoting, that whoever should find and bury his body, should have his lands at Plymstock.

"The furste that fyndes and bringes me to my grave,The landes of Plymstoke they shal have."This couplet was found on his person afterwards. Childe, having no issue, had previously declared his intention of bestowing his estates upon the church wherein he might be buried, which coming to the knowledge of the monks of Tavistock, they eagerly seized the body, and were conveying it to that place; but learning on the way, that some people of Plymstock were waiting at a ford to intercept the prey, they cunningly ordered a bridge to be built out of the usual track, thence pertinently called Guile-bridge, and succeeding in their object, became possessed of the lands until the dissolution, when the Russell family received a grant of them, and still retain it.

In memory of Childe, a tomb was erected to him in a place a little below Fox-tor, where he perished, which stood perfect till about fifteen years since; but it has been destroyed by some ignorant "landlord or tenant," for building materials, and it is now in a ruinous condition. It was composed of hewn granite, the under basement comprising four stones, six feet long by four square, and eight stones more, growing shorter as the pile ascended, with an octagonal basement, above three feet high, and a cross affixed to it. The whole, when perfect, wore an antique and impressive appearance, and it may now, as it is, be looked upon as an object of antiquity and curiosity.

A socket and groove for the cross, and the cross itself, with its shaft broken, are the only remains of this venerable tomb, on which Risdon says there was an inscription, but now no traces of it are visible.

W. H. H.

REMEMBER THEE

(For the Mirror.)Remember thee! thou wouldst not cherish—breathe,One claim for Memory in a heart like mine;Yet, all it-all its hopes for Heaven, or Earth beneath.Were worthless, if unshared by thee and thine!Remember thee! yes, bound in strongest tiesAre those blest ones, that at thy feet may fall,—The heart whom Fortune such dear bonds denies,Is proud to love thee dearer than them all!Remember thee! there is no shame in this,Though oft my heart may wander, and my eye,Picturing fair shapes of too ideal bliss,Forgets the "cold world of reality."Remember thee! there is no error here—To love the gay, the beautiful, the bright,With fondest passion, then to turn with fearTo sterner duties—tasks forgotten quite.Remember thou that one, who loved thee wellThough scorned, and broken-hearted, and undone,When, without shame, thy ruby lips may tellHow deep the passion of that nameless one!Remember! oh, remember! in those yearsWhich fleet so fast—which I may never see;Then, whilst I linger in this "vale of tears,"What should I think upon, but God and thee!THOMAS M–s.

ANCIENT ROMAN FESTIVALS

AUGUST

(For the Mirror.)The Portumnalia was a festival in honour of Portumnus, who was supposed to preside over ports and havens, celebrated on the 17th of August, in a very solemn and lugubrious manner, on the borders of the Tiber.

The Vinalia were festivals in honour of Jupiter and Venus. The first was held on the 19th of August, and the second on the 1st of May. The Vinalia of the 19th of August were called Vinalia Rustica, and were instituted on occasion of the war of the Latins against Mezentius; in the course of which war, that people vowed a libation to Jupiter of all the wine in the succeeding vintage. On the same day likewise fell the dedication of a temple to Venus; whence some authors have fallen into a mistake, that these Vinalia were sacred to Venus.

The Consuales Ludi, or Consualia, were festivals at Rome in honour of Consus, the god of counsel, whose altar Romulus discovered under the ground. This altar was always covered, except at the festival, when a mule was sacrificed, and games and horse-races exhibited in honour of Neptune. It was during these festivals (says Lempriere) that Romulus carried away the Sabine women, who had assembled to be spectators of the games. They were first instituted by Romulus. Some say, however, that Romulus only regulated and re-instituted them after they had been before established by Evander. During the celebration, which happened about the middle of August, horses, mules, and asses were exempted from all labour, and were led through the streets adorned with garlands and flowers.

The Volturnalia was a festival kept in honour of the god Volturnus, on the 26th of August.

The Ambarvalia were festivals in honour of Ceres, in order to procure a happy harvest. At these festivals they sacrificed a bull, a sow, and a sheep, which, before the sacrifice, were led in procession thrice around the fields; whence the feast is supposed to have taken its name, ambio, I go round, and arvum, field. These feasts were of two kinds, public and private. The private were solemnized by the masters of families, accompanied by their children and servants, in the villages and farms out of Rome. The public were celebrated in the boundaries of the city, and in which twelve fratres arvales walked at the head of a procession of the citizens, who had lands and vineyards at Rome. These festivals took place at the time the harvest was ripe.

The Vulcanalia were festivals in honour of Vulcan, and observed at the latter end of August. The streets of Rome were illuminated, fires kindled every where, and animals thrown into the flames as a sacrifice to the deity.

P.T.W.

THE NOVELIST

BEBUT THE AMBITIOUS

"Hear this true story, and see whither you may be conducted by ambition."

HAFIZ, the Persian Poet.In one of the suburbs of Ispahan, under the reign of Abbas the First, there lived a poor, working jeweller. In his neighbourhood he was known by the name of Bebut the Honest. Numberless were the proofs of probity and disinterestedness which had gained for him this title.

In all disputes and quarrels, he was the chosen arbiter. His decisions were generally as conclusive as those of the Kazi himself. Laborious, active, and intelligent, and esteemed by all who knew him, Bebut was happy; and his happiness was still enhanced by love. Tamira, the beautiful daughter of his patron, was the object of his attachment, which she returned. One thought alone disturbed his felicity; he was poor, and the father of Tamira would never accept a son-in-law without a fortune. Bebut, therefore, often meditated upon the means of getting rich. His thoughts dwelt so much on this subject, that ambition at length became a dangerous rival to the softer sentiment.

There was a grand festival in the harem. In the midst of it, the great Schah Abbas dropped the royal aigrette, called jigha, the mark of sovereignty among the Mussulmans. In changing his position, that it might be sought for, he inadvertently trod upon it, and it was broken. The officer who had charge of the crown jewels, knew the reputation of Bebut; to him he applied to repair this treasure. None but the most honest could be trusted with an article of such value, and who was there so honest as Bebut? Bebut was enraptured with the confidence. He promised to prove himself deserving of it.

Now Bebut holds in his hands the richest gems of Persia and the Indies. Ambition has already stolen into his bosom. Could it be silent on an occasion like this? It ought to have been so, but it was not.

"A single one of these numerous diamonds," said Bebut to himself, "would make my fortune and that of Tamira! I am incapable of a breach of trust; but were I to commit one, would Abbas be the worse for it? No, so far from it, he would have made two of his subjects happy without being aware. Now, any body else situated as I am, would manage to put aside a vast treasure out of a job like this; but one, and that a very small one, of these many gems will be enough for me. It will be wrong, I confess, but I will replace it by a false one, cut and enchased with such exquisite taste and skill, that the value of the workmanship shall make up for any want of value in the material. It will be impossible to see the change; God and the Prophet will see it plainly enough, I know; but I will atone for the sin, and it shall be my only one. Sometime or other I will go a pilgrimage to Mashad, or even to Mecca, should my remorse grow troublesome."

Thus, by the power of a "but," did Bebut the Honest contrive to quiet his conscience. The diamond was removed: a bit of crystal took its place, and the jigha appeared more brilliant than ever to the courtiers of Abbas, who, as they never spoke to him but with their foreheads in the dust, could, of course, form a very accurate estimate of the lustre of his jewels.

One day during the spring equinox, as the chief of the sectaries of Ali, according to the custom of Persia, was sitting at the gate of his palace to hear the complaints of his people, a mechanic from the suburb of Julfa broke through the crowd; he prostrated himself at the feet of the Abbas, and prayed for justice; he accused the kazi of corruption, and of having condemned him wrongfully. "My adversary and I," said he, "at first appealed to Bebut the Honest, who decided in my favour." Being informed who this Bebut was whose name for honesty stood so high in the suburb of Julfa, the Schah ordered the kazi into his presence. The monarch heard both sides and weighed the affair maturely. He then pronounced for the decision of Bebut the Honest, whom he ordered the kalantar, or governor of the city, immediately to bring before him.

When Bebut saw the officer and his escort halt before the shop where he worked, a sudden tremor ran through his frame; but it was much worse when, in the name of the Schah, the officer commanded him to follow. He was on the point of offering his head at once, in order to save the trouble of a superfluous ceremony which could not, he thought, but end with the scimitar. However, he composed himself, and followed the kalantar.

Arrived before Abbas, he did not dare lift his eyes, lest he should see the fatal aigrette, and the false diamond rise up in judgment against him. Half dead with fright, he thought he already beheld the fierce rikas advancing with their horrid hatchets.

"Bebut, and you, Ismael-kazi," said Abbas to them, "listen. Since, of the two, it is the jeweller who best administers justice, let the jeweller be a judge, and the judge be a jeweller. Ismael, take Bebut's place in the workshop of his master: may you acquit yourself as well in his office, as he is sure to do in yours."

The sentence was punctually executed; and I am told that Ismael turned out an excellent jeweller.

Bebut-kazi, on his side, took possession of his place. He was quite determined to limit his ambition to becoming the husband of Tamira, and living holily. He immediately asked her in marriage, and was immediately accepted. Bebut thought himself at the summit of his wishes. He was forming the most delightful projects, when again the kalantar of Ispahan appeared at his door. Still, full of the fright into which this worthy person's first visit had thrown him, he received him with more flurry than politeness. He inquired, confusedly, to what he was indebted for the honour of this second visit. The kalantar replied, "When I went to the house of your patron to transmit to you the mandate of the magnanimous Abbas, I saw there the beautiful Tamira with the gazelle eyes, the rose of Ispahan, brilliant as the azure campac which only grows in Paradise. Her glance produced on me the magical effect of the seal of Solomon, and I resolved to take her for my wife. I went this very morning to her father, but his word was given to you; and Bebut-kazi is the only obstacle to my happiness. Listen! I possess great riches, and have powerful friends; give up to me your claim on Tamira, and, ere long, I will get you appointed divan-beghi; you shall be the chief sovereign of justice in the first city in the universe; I will give you my own sister for a wife, she who was formerly the nightingale of Iran, the dove of Babylon. I leave you to reflect on my offer; to-morrow I return for the answer."

The new kazi was thunderstruck. "What! yield my Tamira to him for his sister! Why, she may be old and ugly; 'tis like exchanging a pearl of Bahrein for one of Mascata; but he is powerful. If I do not consent, he will deprive me of my place; and I like my place; and yet I would freely sacrifice it for Tamira. But were I no longer kazi, would her father keep his promise? Doubtful. I love Tamira more than all the world; but we must not be selfish; we must forget our own interest, when it injures those we love. To deprive Tamira of a chance of being the wife of a kalantar would be doing her an injury. How could I have the heart to force her to forego such a glory, merely for the sake of the poor insignificant kazi that I am! I should never get over it; 'tis done! I will immolate my happiness to hers! I shall be very wretched; but—but—I shall be divan-beghi."

If Bebut the Honest, misled by dawning avarice, fancied he committed his first fault for the sake of love, and not of ambition, he must have been undeceived when these two rival passions came into competition, and he could only banish the first. If his eyes were not opened, those of the world began to be; for, from that moment, he lost (when he had more need of them than ever) the esteem and confidence he had hitherto inspired, and became known by the name of Bebut the Ambitious.

Not yet aware that the higher we rise in rank, the harder we find it to be virtuous, he was for ever flattering himself with the future. Now, his conduct was to be such as should edify the whole body of the magistracy of Ispahan, of which he was become the head. He would not be satisfied with going to Mecca to visit the black stone, the temple of Kaaba, and purifying himself in the waters of Zim-zim, the miraculous spring which God caused to issue from the earth for Agar, and her son Ismael. He would do more; he would distribute a double zekath4 to the poor, and win back for the divan-beghi the noble title which the people gave to the mechanic of the suburb of Julfa.

The first judgment which he pronounced as divan-beghi, bore evidence of this excellent resolution; but an unfortunate event occurred, which proved the truth of the following verse of the renowned Ferdusi, in his poem of the "Schah-nameh."5

"Our first fault, like the prolific poppy of Aboutige, produces seeds innumerable. The wind wafts them away, and we know not where they fall, or when they may rise; but this we know, they meet us at every step upon the path of life, and strew it with plants of bitterness."

The royal aigrette of Schah Abbas was again broken, and immediately confided to an old comrade of Bebut. He had not, however, the surname of "Honest," and his work was consequently subjected to a cautious scrutiny. Now, it was discovered that a very fine diamond had been taken from the jigha and fraudulently replaced; the unfortunate jeweller was arrested and dragged to the tribunal of the divan-beghi. The ambitious Bebut felt that there was no chance for him if he did not hurry the affair to an immediate close. He forthwith condemned his innocent fellow-labourer to the punishment due to his own iniquity, and the sentence was executed on the instant.