полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 363, March 28, 1829

Bolivar having proposed to take the town of Santa Marta, still held by the Spaniards, he was authorized by the government of Santa Fé to procure guns, &c., from the arsenals of Carthagena. The governor of that fortress refused to furnish the necessary supplies. In order to enforce compliance, Bolivar invested Carthagena, before which he remained a considerable time, when he heard of the arrival at Margarita of General Morillo, with ten thousand Spanish troops. Upon this, Bolivar placed his own investing force at the disposal of his rival, the governor of Carthagena; and, unwilling that the cause of his country should continue to suffer from the dissention which had arisen between himself and the governor, withdrew to Jamaica. Morillo, soon afterwards, laid siege to Carthagena, which, unfortunately, in consequence of the long investment it had already sustained, was nearly destitute of provisions, Bolivar sent from Jamaica some supplies for the besieged garrison; but before they could arrive, that important fortress was in possession of the Spaniards. This enabled them to reconquer New Granada, and the blood of its citizens was made to stream from the scaffold.

At Kingston, Bolivar narrowly escaped assassination. The casual circumstance of exchanging apartments with another person, caused the murderer's dagger to be planted in the heart of a faithful follower, instead of in that of Bolivar. The author of these memoirs happened to live, for a few days, in the same boarding-house. Some officers of a British line-of-battle ship, not speaking Spanish, requested him to invite Bolivar, in their name, to dine with them. This was only a few weeks previous to the intended assassination of Bolivar.

From Jamaica, Bolivar went to Hayti, and was received at Port-au-Prince by Petion with kind hospitality, and was assisted by him as far as his means would allow.

In April, 1816, he sailed with three hundred men to Margarita, which island had lately again shaken off the Spanish yoke. He arrived at Juan Griego, where he was proclaimed supreme chief of the republic. On the 1st of June he sailed, and on the 3rd landed at Campano, where he beat nine hundred Spaniards. He then opened a communication with patriot chieftains, who had maintained themselves in isolated parties dispersed over the llanos of Cumaná, Barcelona, and the Apure. It is a curious fact, that the isolation of several of these parties was so complete, that, for many months, they did not know of any other than themselves being in arms for the delivery of their country. It was only by their coming into accidental contact that they discovered that there was more than one patriot guerilla in existence.3 Bolivar supplied some of them with arms, and at the same time augmented his own force to a thousand men. The Spaniards assembled in superior numbers to destroy them; but Bolivar embarked, and relanded at Ocumare, with an intention of taking Caracas: great part, however, of the Spanish army having by this time returned from New Granada to Venezuela, Bolivar was obliged to re-embark for Margarita.

In 1817, he landed near Barcelona, where he collected seven hundred recruits, and marched towards Caracas; but, being worsted in an affair at Clarines, he fell back again upon Barcelona, where he shut himself up with four hundred men, and made a successful resistance against a superior force.

Bolivar received some reinforcements from the interior of the province of Cumaná, upon which he decided upon making the banks of the Orinoco the theatre of his future efforts. Having further augmented his force, and taken the necessary steps to keep alive the war in the districts on the coast, he marched to the interior, beating several small royalist parties which he encountered on his route.

Of the Spanish army which had returned from New Granada, a division, under the brave General La Torre, was destined to act against the patriots in Guayana. A division of the latter, under General Piar, having obtained a decisive victory, Bolivar was enabled to invest Angostura, and the town of old Guyana, which were successively taken on the 3rd and 18th of July.

In Angostura, Piar was found guilty, by a court-martial, of an attempt to excite a war of colour. Piar (a man of colour himself) was the bravest of the brave, and adored by his followers; but his execution stifled anarchy in the bud.

The rest of the year 1817 was actively spent in organizing a force to act against Morillo, who had lately been reinforced by two thousand fresh troops from the Peninsula, under General Canterac, then on his way from Spain to Peru. An abundant supply of arms, received from England, was sent to the patriot corps on the banks of the Apure.

(To be continued.)LEDYARD TO HIS MISTRESS

(For the Mirror.)Dost wish to roam in foreign climesForget thy home and long past times?Dost wish to be a wand'rer's bride,And all thy thoughts in him confide?Thou canst not traverse mountain seas,Nor bear cold Lapland's freezing breeze;Thou canst not bear the torrid heats,Nor brave the toils a wand'rer meets;Thou wouldst faint, dearest, with fatigueTrav'ling the desert's sandy league.Pale hunger with her sickly painsWill silence thy heroic strains;Thy heart—now warmly beats—will chillAnd stop thy lover's wonted skill.He could not see thee pine and weepNor could he ease thy troubled sleep—'Twould quite unman his firm resolve,And with grief thy love involve.Terrenus.

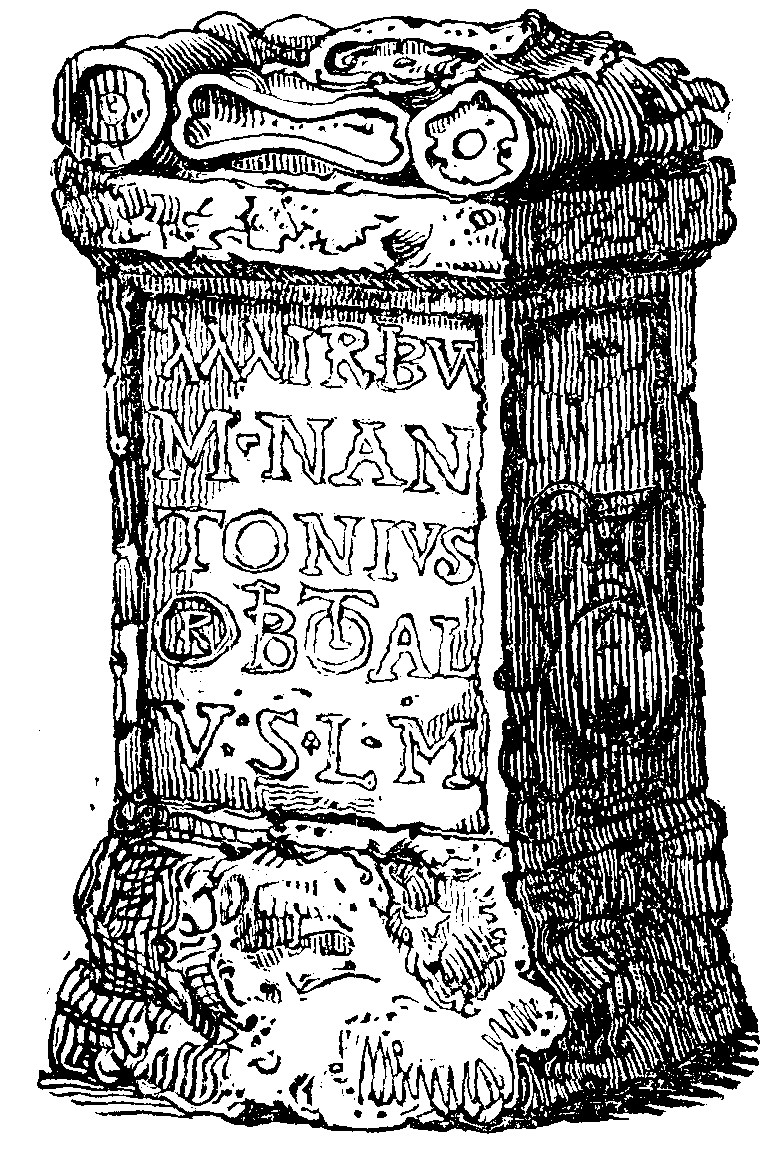

ROMAN ALTAR

Enclosed I send you a drawing of a Roman votive altar, which was found in digging a cellar about six feet deep, in St. Sepulchre's Gate, Doncaster, in the year 1781. It is the oldest relic of antiquity which Doncaster has yet produced, and is of exquisite engraving and workmanship. Upon the capital, or top of the stone, a small space above the sculpture of the altar itself, is a crater or flowing bowl,4 sacred to Bacchus, the god of wine; on the dexter, or right side of the altar, is a flower-pot, or cornucopiæ, with five branches in it, loaded with leaves and fruit, sacred to Ceres, or Terra-Mater, the goddess of plants; and on the sinister, or left side thereof, is a large jug or pitcher with a large handle, also sacred to Bacchus. It is about 2 feet 6-1/2 inches in height, and 1 foot in breadth at the base. The corporation employed a Mr. Richard John Tetlow, of Ferrybridge, a celebrated antiquary, to interpret the inscription, and give them his opinion on its age. They also sent it to the Antiquarian Society in London for inspection.

Interpretation of the SocietyMatribus magnis,5 Nantonius6 Orberthol, vota solvit lubens merito.

TranslationTo the great mothers, (goddesses,) Anthony Orberthol willingly and meritoriously has performed his vows or promises.

Interpretation of Mr. TetlowLunæ, Latonæ, Lucinæ, Matribus magnis Antonius Orbis Romani Imperator Bonis Oeis Altare. vota. solvit. lubens merito.

TranslationTo Luna, Latona, Lucina, the great good mothers, goddesses, Anthony, the emperor of the Roman empire, hath erected, or dedicated, this altar. Freely and fully he has discharged his vows and promises.

It is, reasonably enough, conjectured from several corroborative circumstances, that the altar above described is no less than 1,645 years old. One of these circumstances is its being similar in some respects to two other Roman altars which were found in England some years back, one of which is related to have been made in the year of Christ 161.

Near Sheffield. J. M. C–d.

NOTES OF A READER

SUNSET

Day sets in glory, and the glowing airSeems dreaming in delight; peace reigns around,Save where some beetle starteth here and thereFrom the shut flowers that kiss the dewy ground—A burning ocean, stretching vast and farThe parting banners of the king of light,Gleam round the temples of each living starThat comes forth in beauty with the night:The west seems now like some illumined hall,Where beam a thousand torches in their pride,As if to light the joyous carnivalHeld by the bright sun and his dark-robed bride,Whose cloudy arms are round his bosom press'd,As with her thousand eyes she woos him to his rest.The African, a Tale.

BEES

Alternations of torpor and animation cause greater exhaustion and loss of physical powers, than would be occasioned by a continuance of uniform torpor. This we infer from the fact, that in Russia, where the winters are uniformly cold, bees do not perish; and in the West Indies where there is perpetual verdure, they are never exhausted.

Major Rennell—clarum et venerabile nomen—now in his 87th year, possesses in full vigour, for the happiness of himself and friends, all those intellectual faculties which have so eminently distinguished his long and useful life; who, suffering little short of martyrdom, from the frequent attacks of gout, still devotes hours and days to his favourite pursuit; uniting with his studies all the playfulness and vivacity of youth.

Quarterly Review.

WAR

War! what miseries are heaped together in the sound!–What an accumulation of curses is breathed in that one word. To us, happy in our insular position, we have, within existing memory, known chiefly of war, its pomp and circumstance alone; the gay parade, the glancing arms, the bright colours, the inspiring music—these are what we see of war in its outset;—glory, and praise, and badges of honour, these are what appear to us as its result. The favourite son, the beloved brother, he who, perhaps, is dearer still, returns to the home of his youth or of his heart, having sown danger and reaped renown. Thus do we look on war. But ask the inhabitant of a country which has been the seat of war, what is his opinion of it. He will tell you that he has seen his country ravaged, his home violated, his family – But no! the tongue recoils from speaking the horrors and atrocities of war thus brought into the bosom of a peaceful home. All the amenities and charities of domestic life are outraged, are annihilated. All that is dearest to man; all that tends to refine, to soften him—to make him a noble and a better being—all these are trampled under foot by a brutal soldiery—all these are torn from his heart for ever! He will tell you that he detests war so much that he almost despises its glories; and that he detests it because he has known its evils, and felt how poorly and miserably they are compensated by the fame which is given to the slaughterer and the destroyer, because he is such!

Tales of Passion.

THE NEWSPAPERS

These square pieces of paper are the Agoras of modern life. The same skilful division of labour which brings the fowl ready trussed to our doors from the market, brings also an abstract of the

Votum, timor, ira, voluptas,Gaudia, discursus,which agitate the great metropolis, and even opinions, ready prepared, to the breakfast tables of our remotest farms, ere the controversial warmth has had time to cool. In the centre of this square, where you observe the larger character, a public orator, "vias et verba locans," takes his daily stand. One makes his speech in the morning, and another reserves his for the evening; a third class, either disposed to take less trouble, or, finding it convenient to construct their speeches from fragments of the daily orations, harangue once in two or three days; while a fourth waylay the people in their road to visit the temples on our hebdomadal festivals. But cast your eyes to another part of these our artificial forums, and observe the number of small divisions which fill up the space. There are stalls of merchandize. The ancient venders must have been noisy, and a frequent cause of annoyance to political speakers; but here the hawkers of wet and dry goods, the hawkers of medicine, the hawkers of personal services, the hawkers of husbands and wives, (for among us these articles are often cried up for sale,) and lastly, the hawkers of religions, moral, and political wisdom, all cry out at once, without tumult or confusion, yet so as to be heard in these days through the remotest corners of these islands.... If a peculiarly bloody murder has been tried, or if some domestic intrigue has produced a complicated love story, however offensive in its details, you will find our reading crowd stationary in that quarter, to enjoy the tragic stimulants of terror and pity. We have also a modest corner of the square appropriated to the use of our posts; but like Polydorus's ghost, they generally utter doleful soliloquies, which no one will stop to hear.

London Review.

BEAUTY

It is vain to dispute about the matter; moralists may moralize, preachers may sermonize about it as much as they please; still beauty is a most delightful thing,—and a really lovely woman a most enchanting object to gaze on. I am aware of all that can be said about roses fading, and cheeks withering, and lips growing thin and pale. No one, indeed, need be ignorant of every change which can be rung upon this peal of bells, for every one must have heard them in every possible, and impossible, variety of combination. Give time, and complexion will decay, and lips and cheeks will shrink and grow wrinkled, sure enough. But it is needless to anticipate the work of years, or to give credit to old Time for his conquests before he has won them. The edge of his scythe does more execution than that of the conqueror's sword: we need not add the work of fancy to his,—it is more than sufficiently sure and rapid already.

Tales of Passion.

PRE-AUX-CLERCS

In 1559, the most frequented promenade in Paris was the Pré-aux-Clercs, situated where a part of the Faubourg St. Germain is at present. The students of the university were generally in favour of the reformed religion, and not only made a profession of it, but publicly defended its principles. They had been in the habit of meeting at this place for several years, and the monks of the Abbey St. Victor having refused to let them assemble in the Pré-aux-Clercs, a serious affair sprung out of the refusal, and several rencounters took place, in which blood was shed; the students, being the most numerous, carried their point, the monks resigned the field to them, and the Pré-aux-Clercs was more than ever frequented. It became the grand rendezvous of all the Protestants, who would sing Marot's psalms during the summer evenings; and such numbers giving confidence, many persons declared themselves Protestants, whose rank had hitherto deterred them from such a step. Among such, the most eminent was Anthony of Bourbon, first prince of the blood, and, in right of his wife, king of Navarre.

Browning's History of the Hugonots.

LOVE

When she learned the vocabulary, she did not find that admiration meant love; she did not find that gratitude meant love; she did not find that habit meant love; she did not find that approbation meant love; but in process of time she began to suspect that all these put together produced a feeling very much like love.

Rank and Talent.

HUGONOTS

Various definitions of this epithet exist. Pasquier says it arose from their assembling at Hugon's Tower, at Tours; he also mentions, that in 1540 he heard them called Tourangeaux. Some have attributed the term to the commencement of their petitions, "Huc nos venimus." A more probable reason is to be found in the name of a party at Geneva, called Eignots, a term derived from the German, and signifying a sworn confederate. Voltaire and the Jesuit Maimbourg are both of this opinion.

Browning's History of the Hugonots.

A ROUT

A great, large, noisy, tumultuous, promiscuous, crowding, crushing, perfumed, feathered, flowered, painted, gabbling, sneering, idle, gossiping, rest-breaking, horse-killing, panel-breaking, supper-scrambling evening-party is much better imagined than described, for the description is not worth the time of writing or reading it.

Rank and Talent.

PLEASURE

We are mad gamesters in this world below,All hopes on one uncertain die to throw;How vain is man's pursuit, with passion blind,To follow that which leaves us still behind!Go! clasp the shadow, make it all thine own,Place on the flying breeze thine airy throne;Weave the thin sunbeams of the morning sky;Catch the light April clouds before they fly;Chase the bright sun unto the fading west,And wake him early from his golden rest;Seeking th' impossible, let life be past,But never dream of pleasure that shall last.The Ruined City.

GERMAN LIFE

One day (says a late adventurer,) that I was quartered in a farm-house, along with some of our German dragoons, the owner came to complain to me that the soldiers had been killing his fowls, and pointed out one man in particular as the principal offender. The fact being brought home to the dragoon, he excused himself by saying, "One shiken come frighten my horse, and I give him one kick, and he die." "Oh, but," said I, "the patron contends that you killed more than one fowl." "Oh yes; that shiken moder see me kick that shiken, so she come fly in my face, and I give her one kick, and she die." Of course I reported the culprit to his officer, by whom he was punished as a notorious offender.

Twelve Years' Military Adventures.

THE HEIR

Persons who are very rich, and have no legal heirs, may entertain themselves very much at the expense of hungry expectants and lean legacy-hunters. Who has not seen a poor dog standing on his hind legs, and bobbing up and down after a bone scarcely worth picking, with which some mischief-loving varlet has tantalized the poor animal till all its limbs have ached? That poor dog shadows out the legacy-hunter or possible heir.

Rank and Talent.

The author of "The Journal of a Naturalist," just published, relates the following incident that occurred a few years past at a lime-kiln, (on the old Bristol Road) because it manifests how perfectly insensible the human frame may be to pains and afflictions in peculiar circumstances; and that which would be torture if endured in general, may be experienced at other times without any sense of suffering. A travelling man one winter's evening laid himself down upon the platform of a lime-kiln, placing his feet, probably numbed with cold, upon the heap of stones newly put on to burn through the night. Sleep overcame him in this situation; the fire gradually rising and increasing until it ignited the stones upon which his feet were placed. Lulled by the warmth, he still slept; and though the fire increased until it burned one foot (which probably was extended over a vent hole) and part of the leg, above the ankle, entirely off, consuming that part so effectually, that no fragment of it was ever discovered; the wretched being slept on! and in this state was found by the kiln-man in the morning. Insensible to any pain, and ignorant of his misfortune, he attempted to rise and pursue his journey, but missing his shoe, requested to have it found; and when he was raised, putting his burnt limb to the ground to support his body, the extremity of his leg-bone, the tibia, crumbled into fragments, having been calcined into lime. Still he expressed no sense of pain, and probably experienced none, from the gradual operation of the fire and his own torpidity during the hours his foot was consuming. This poor drover survived his misfortunes in the hospital about a fortnight; but the fire having extended to other parts of his body, recovery was hopeless.

GAMING

Gambling, the besetting sin of the indolent in many countries, is ruinously general throughout South America. In England, and other European states, it is pretty much limited to the unemployed of the upper classes, who furnish a never-ending supply of dupes to knavery. In South America the passion taints all ages, both sexes, and every rank. The dregs of society yield to the fascination as blindly as the high-born and wealthy of the old or of the new world. It speaks much in favour of the revolution, that this vice is sensibly diminishing in Peru, and to the unfortunate Monteagudo belongs the honour of having been the first to attempt its eradication. A noted gambler was once as much an object of admiration in South America as a six-bottle man was in England fifty years ago. The houses of the great were converted into nightly hells, where the priesthood were amongst the most regular and adventurous attendants. Those places are now more innocently enlivened by music and dancing. Buena Vista, a seat of the late Marquess of Montemira, six leagues from Lima, was the Sunday rendezvous of every fashionable of the capital who had a few doubloons to risk on the turn of a card. On one occasion, a fortunate player, the celebrated Baquijano, was under the necessity of sending for a bullock car to convey his winnings, amounting to above thirty thousand dollars: a mule thus laden with specie was a common occurrence. Chorillos, a fishing town, three leagues south of Lima, is a fashionable watering place for a limited season. Here immense sums are won and lost; but political and literary coteries, formerly unknown, daily lessen the numbers of the votaries of fortune.

So strong was this ruling passion, that when the patriot army has been closely pursued by the royalists, and pay has been issued to lighten the military chest, the officers, upon halting, would spread their ponchos on the ground, and play until it was time to resume the march; and this was frequently done even on the eve of a battle. Soldiers on piquet often gambled within sight of an enemy's advanced post.

Memoirs of Gen. Miller.

THE NATURALIST

VOLCANIC ISLAND OF ST. CHRISTOPHER

This island is entirely composed of volcanic matter, in some places alternating with submarine productions. The principal mountain is situated at the western end of the island; it is an exhausted volcano, called in books of navigation, charts, &c., Mount Misery. The summit of this mountain is 3,711 feet above the sea; it appears to consist of large masses of volcanic rocks, roasted stones, cinders, pumice, and iron-clay. The whole extent of land, to the sea-shore on either side, may be considered as the base of this mountain, as it rises with a pretty steep ascent towards it; but from the part which is generally considered the foot of the mountain, it takes a sudden rise of an average angle of about 50 degrees. To the east, another chain of mountains runs, of a similar formation, though of inferior height. On the summits of these there are no remains that indicate their having ever possessed a crater: so that whether any of them have originally been volcanoes, or whether they have been formed by an accumulation of matter thrown out of Mount Misery, it is difficult to decide. That the low lands have been thrown from the mouth of the volcano is evident, from the regular strata of volcanic substances of which they consist; these too are interspersed with masses of volcanic rock, and other stones, some of the lesser ones entirely roasted through, and some of the larger ones to certain depths from their surfaces. Masses, also, of iron-clay, enclosing various pebbles, which have been burnt into a kind of red brick, are abundantly found in many places. There is scarcely any thing that can be called a path, or even a track, to the mouth of the crater of Mount Misery; indeed, there are but few whose curiosity is sufficiently strong to induce them to undertake this expedition. The common course for those who do, is to take a negro man as a guide, with a cutlass, or large knife, to clear away the underwood, and form a kind of path as he goes on. The ascent is very irregular, in some places being gentle, in others almost perpendicular; in which case the hands are obliged to assist the operations of the feet. In wet weather, the ascent of this mountain is extremely laborious, as a great part of it consists of clay, which then becomes so slippery as to render the getting up almost impracticable. About half-way up on the south side, and in a very pretty, romantic situation, there is a natural spring of remarkably cool water. On the north side, at about the same height, there is a waterfall, which, though small and insignificant in itself, has a pleasing appearance, as it rushes over the rocks, and through the trees and shrubs. This mountain is thickly clothed with wood, which in many places not only excludes the rays of the sun, but produces a sombre, gloomy appearance; this, with the occasional plaintive coo of the mountain dove, (the only sound heard at this height,) creates in the mind sensations of pleasing melancholy. In some parts an open space suddenly appears, from whence the whole country below bursts unexpectedly upon the view, which has, as may be supposed, an extremely fine effect. The thermometer, on the top of the mountain when the writer visited it, stood at 65, being a difference of 15 degrees from the low lands, where it stood at 80 degrees. The descent into the crater on the north and east sides is perfectly perpendicular; on the south and west sides, it slopes at an average angle of not more than 18 or 20 degrees from the perpendicular; consequently, persons descending are often obliged to let themselves down by clinging to projecting corners of rocks, or the branches and roots of shrubs, which grow all the way down; nor is this mode of travelling particularly safe, for should any of these give way, the consequence would probably be highly dangerous. The bottom of the crater, which, as nearly as could be estimated, is about 2,500 feet below the summit of the mountain, and contains about forty-five or fifty acres, may be said to be divided into three parts: the lowest side (to the south) consists of a large pond or lake, formed entirely by the rain-water collected from the sides of the crater—accordingly its extent is greater or less, as the season is wet or dry; the centre part is covered with small ferns, palms, and shrubs, and some curious species of moss; the upper part, to the north, is that which is called the Soufriere. The ground here consists of large beds of pipe-clay, in some places perfectly white, in others of a bluish or black colour, from the presence of iron pyrites. These are intermixed with masses and irregular beds of gray cinders and score, pumice, various kinds of lava, lithomarge, and fuller's earth. Amidst these beds of clay there are several hot springs, small, but boiling with much violence, and emitting large quantities of steam. A rumbling noise is heard under the whole of this part of the crater. The hot springs are not stationary, but suddenly disappear, and burst up in another place. The ground in many parts is too hot to be walked upon: a great quantity of sulphuretted hydrogen gas is likewise emitted, which is exceedingly disagreeable to the smell; and occasionally such a volume of it arises, as is almost suffocating, and resembles much the smell of rotten eggs. The watches of the writer and his companion during his visit, and every article of gold or silver about their persons, were in a few moments turned perfectly black, from the effect of this gas.