полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 14, No. 381, July 18, 1829

NEAPOLITAN SUPERSTITION

The Neapolitan sailors never go to sea without a box of small images or puppets, some of which are patron saints, inherited from their progenitors, while others are more modern, but of tried efficacy in the hour of peril. When a storm overtakes the vessel, the sailors leave her to her fate, and bring upon deck the box of saints, one of which is held up, and loudly prayed to for assistance. The storm, however, increases, and the obstinate or powerless saint is vehemently abused, and thrown upon the deck. Others are held up, prayed to, abused, and thrown down in succession, until the heavens become more propitious. The storm abates, all danger disappears, the saint last prayed to acquires the reputation of miraculous efficacy, and, after their return to Naples, is honoured with prayers.—Ibid.

The Naturalist

LENGTH AND FINENESS OF THE SILKWORM'S WEB, &c

Baker in The Microscope made Easy, says, "A silkworm's web being examined, appeared perfectly smooth and shining, every where equal, and much finer than any thread the best spinster in the world can make, as the smallest twine is finer than the thickest cable. A pod of this silk being wound off, was found to contain 930 yards; but it is proper to take notice, that as two threads are glewed together by the worm through its whole length, it makes double the above number, or 1,860 yards; which being weighed with the utmost exactness, were found no heavier than two grains and a half. What an exquisite fineness is here! and yet, this is nothing when compared with the web of a small spider, or even with the silk that issued from the mouth of this very worm, when but newly hatched from the egg."

Under the article Silk, in Rees's Cyclopaedia, the writer says, "that those who have examined it attentively, think they speak within compass, when they affirm that each ball contains silk enough to reach the length of six English miles."

Baker tells us, "not to neglect the skins these animals cast off three times before they begin to spin; for the eyes, mouth, teeth, ornaments of the head, and many other parts may be discovered better in the cast-off skins than in the real animal."

P.T.WCUCKOO

Mr. Jerdan, editor of the Literary Gazette, in a letter to Mr. Loudon, says, "about fifteen years ago I obtained a cuckoo from the nest of (I think) a hedge sparrow, at Old Brompton, where I then resided. It was rather curious, as being within ten yards of my house, Cromwell Cottage, and in a narrow and much frequented lane, leading from near Gloucester Lodge to Kensington. This bird I reared and kept alive till late in January; when it fell suddenly from its perch, while feeding on a rather large dew worm. It was buried: but I had, long afterwards, strange misgivings, that my poor feathered favourite was only choked by his food, or in a fit of some kind—his apparent death was so extremely unexpected from his health and liveliness at the time. I assure you that I regretted my loss much, my bird being in full plumage and a very handsome creature. He was quite tame, for in autumn I used to set him on a branch of a tree in the garden, while I dug worms for him to dine upon, and he never attempted more than a short friendly flight. During the coldest weather, and it was rather a sharp winter, my only precaution was, nearly to cover his cage with flannel; and when I used to take it off, more or less, on coming into my breakfast room in the morning, I was recognised by him with certainly not all the cry "unpleasant to a married ear," but with its full half "Cuck! Cuck!"—the only sounds or notes I ever heard from my bird. Though trifling, these facts may be so far curious as illustrating the natural history of a remarkable genus, and I have great pleasure in offering them for your excellent Journal." Mag. Nat. Hist.

MUSICAL SNAILS

As I was sitting in my room, on the first floor, about nine P.M. (4th of October last), I was surprised with what I supposed to be the notes of a bird, under or upon the sill of a window. My impression was, that they somewhat resembled the notes of a wild duck in its nocturnal flight, and, at times, the twitter of a redbreast, in quick succession. To be satisfied on the subject, I carefully removed the shutter, and, to my surprise, found it was a garden snail, which, in drawing itself along the glass, had produced sounds similar to those elicited from the musical glasses.—Ibid.

BEWICK

In the museum at Newcastle are many of the identical specimens from which the illustrious townsman Bewick drew his figures for the wood-cuts which embellish his unique and celebrated work. This truly amiable man, and, beyond all comparison, greatest genius Newcastle has ever produced, died on the 8th of November last, in the 76th year of his age. He continued to the last in the enjoyment of all his faculties; his single-heartedness and enthusiasm not a jot abated, and his wonder-working pencil still engaged in tracing, with his wonted felicity and fidelity, those objects which had all his life afforded him such delight, and which have charmed, and must continue to charm, all those who have any relish for the pure and simple beauties of nature.—Ibid.

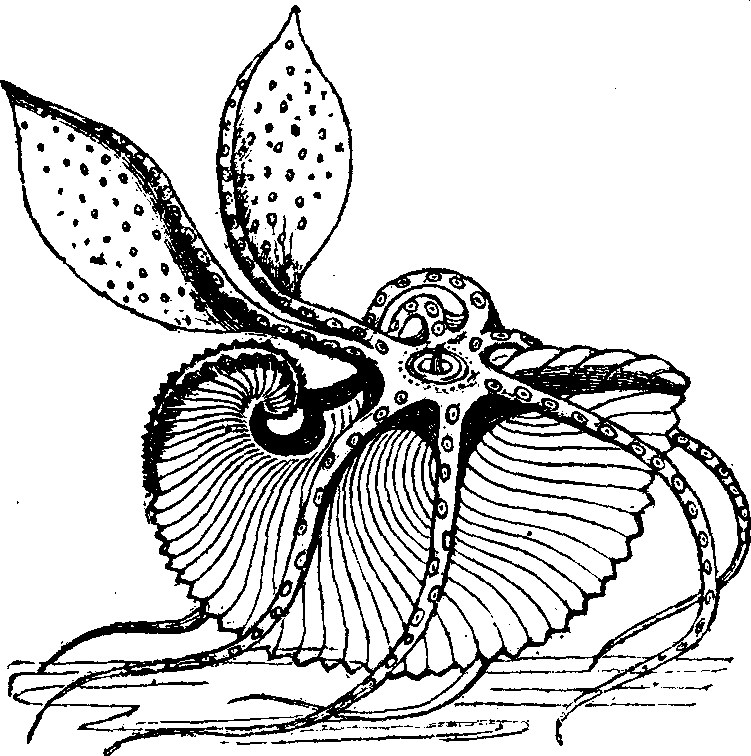

The Argonaut, Or Paper Nautilus

This species of shell-fish, (see the cut,) is named from Argonautes, the companions of Jason, in the celebrated ship, Argo, and from the Latin naus, a ship; the shells of all the Nautili having the appearance of a ship with a very high poop. The shell of this interesting creature is no thicker than paper, and divided into forty compartments or chambers, through every one of which a portion of its body passes, connected as it were, by a thread. In the cut it is represented as sailing, when it expands two of its arms on high, and between these supports a membrane which serves as a sail, hanging the two other arms out of its shell, to serve as oars, the office of steerage being generally served by the tail.

The shell of the Nautilus being exceedingly thin and fragile, the tenant has many enemies, and among others the Trochus who makes war on it with unrelenting fury. Pursued by this cruel foe, it ascends to the top of the water, spreads its little sail to catch the flying breeze, and rowing with all its might, scuds along, like a galley in miniature, and often escapes its more cumbrous pursuer. Sometimes, however, all will not do, the Trochus nears and nears, and escape appears impossible; but when the little animal, with inexplicable ingenuity, suddenly and secretly extricates itself from its tortuous and fragile dwelling, the Trochus immediately turns to other prey. The Nautilus then returns to tenant and repair its little bark; but it too often happens, that before he can regain it, it is by a species of shipwreck, dashed to pieces on the shore. Thus wretchedly situated, this hero of the testaceous tribe seeks some obscure corner "where to die," but which seldom, if ever, happens, until after he has made extraordinary exertions to establish himself anew. What a fine picture of virtue nobly struggling with misfortune.8

When the sea is calm, whole fleets of these Nautili may be seen diverting themselves; but when a storm rises, or they are disturbed, they draw in their legs, take in as much water as makes them specifically heavier, than that in which they float, and then sink to the bottom. When they rise again they void this water by numerous holes, of which their legs are full. The other species of Nautilus, whose shell is thick, never quits that habitation. The shells of both varieties are exceedingly beautiful when polished, and produce high prices among Conchologists.

It is easy to conceive that the ingenious habits of this wonderful creature may have suggested to man the power of sailing upon the sea, and of the various apparatus by which he effects that object. The whole creation abounds with similar instances of Nature ministering to the proud purposes of art: one of them, the origin of the Gothic Arch from the "high o'erarching groves," is mentioned by Warburton, in his Divine Legation, and is a sublime lesson for besotted man.

THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

VIDOCQ

[We have abridged one of the most striking chapters in the very extraordinary history of Vidocq; premising that the interest of the adventure will compensate for the space it here occupies.]

A short time before the first invasion (1814), M. Senard, one of the richest jewellers of the Palais Royal, having gone to pay a visit to his friend the Curè of Livry, found him in one of those perplexities which are generally caused by the approach of our good friends the enemy. He was anxious to secrete from the rapacity of the cossacks first the consecrated vessels, and then his own little treasures. After much hesitation, although in his situation he must have been used to interments, Monsieur le Curè decided on burying the objects which he was anxious to save, and M. Senard, who, like the other gossips and misers, imagined that Paris would be given over to pillage, determined to cover up, in a similar way, the most precious articles in his shop. It was agreed that the riches of the pastor and those of the jeweller should be deposited in the same hole. But, then, who was to dig the said hole? One of the singers in church was the very pearl of honest fellows, father Moiselet, and in him every confidence could be reposed. He would not touch a penny that did not belong to him. The hole, made with much skill, was soon ready to receive the treasure which it was intended to preserve, and six feet of earth were cast on the specie of the Curè, to which were united diamonds worth 100,000 crowns, belonging to M. Senard, and enclosed in a small box. The hollow filled up, the ground was so well flattened, that one would have betted with the devil that it had not been stirred since the creation. "This good Moiselet," said M. Senard, rubbing his hands, "has done it all admirably. Now, gentlemen cossacks, you must have fine noses if you find it out!" At the end of a few days the allied armies made further progress, and clouds of Kirguiz, Kalmucs, and Tartars, of all hordes and all colours, appeared in the environs of Paris. These unpleasant guests are, it is well known, very greedy for plunder: they made, every where, great ravages; they passed no habitation without exacting tribute: but in their ardour for pillage they did not confine themselves to the surface, all belonged to them to the centre of the globe; and that they might not be frustrated in their pretensions, these intrepid geologists made a thousand excavations, which, to the regret of the naturalists of the country, proved to them, that in France the mines of gold or silver are not so deep as in Peru. Such a discovery was well calculated to give them additional energy; they dug with unparalleled activity, and the spoil they found in many places of concealment threw the Croesuses of many cantons into perfect despair. The cursed Cossacks! But yet the instinct which so surely led them to the spot where treasure was hidden, did not guide them to the hiding place of the Curè. It was like the blessing of heaven, each morning the sun rose and nothing new; nothing new when it set.

Most decidedly the finger of heaven must be recognised in the impenetrability of the mysterious inhumation performed by Moiselet. M. Senard was so fully convinced of it, that he actually mingled thanksgivings with the prayers which he made for the preservation and repose of his diamonds. Persuaded that his vows would be heard, in growing security he began to sleep more soundly, when one fine day, which was, of all days in the week, a Friday, Moiselet, more dead than alive, ran to the Curè's.

"Ah, sir, I can scarcely speak."

"What's the matter, Moiselet?"

"I dare not tell you. Poor M. le Curè, this affects me deeply, I am paralyzed. If my veins were open not a drop of blood would flow."

"What is the matter? You alarm me."

"The hole."

"Mercy! I want to learn no more. Oh, what a terrible scourge is war! Jeanneton, Jeanneton, come quickly, my shoes and hat."

"But, sir, you have not breakfasted."

"Oh, never mind breakfast."

"You know, sir, when you go out fasting you have such spasms–."

"My shoes, I tell you."

"And then you complain of your stomach."

"I shall have no want of a stomach again all my life. Never any more—no, never—ruined."

"Ruined—Jesu—Maria! Is it possible? Ah! sir, run then,—run—."

Whilst the Curè dressed himself in haste, and, impatient to buckle the strap, could scarcely put on his shoes, Moiselet, in a most lamentable tone, told him what he had seen.

"Are you sure of it?" said the Curè, perhaps they did not take all."

"Ah, sir, God grant it, but I had not courage enough to look."

They went together towards the old barn, when they found that the spoliation had been complete. Reflecting on the extent of his loss, the Curè nearly fell to the ground. Moiselet was in a most pitiable state; the dear man afflicted himself more than if the loss had been his own. It was terrific to hear his sighs and groans. This was the result of love to one's neighbour. M. Senard little thought how great was the desolation at Livry. What was his despair on receiving the news of the event! In Paris the police is the providence of people who have lost any thing. The first idea, and the most natural one, that occurred to M. Senard was, that the robbery had been committed by the Cossacks, and, in such a case, the police could not avail him materially; but M. Senard took care not to suspect the Cossacks.

One Monday when I was in the office of M. Henry, I saw one of those little abrupt, brisk men enter, who, at the first glance, we are convinced are interested and distrustful: it was M. Senard, who briefly related his mishap, and concluded by saying, that he had strong suspicions of Moiselet. M. Henry thought also that he was the author of the robbery, and I agreed with both. "It is very well," he said, "but still our opinion is only founded on conjecture, and if Moiselet keeps his own counsel we shall have no chance of convicting him. It will be impossible."

"Impossible!" cried M. Senard, "what will become of me? No, no, I shall not vainly implore your succour. Do not you know all? can you not do all when you choose? My diamonds! my poor diamonds! I will give one hundred thousand francs to get them back again."

[Vidocq promises to recover the jewels, and the jeweller offers him 10,000 francs.]

In spite of successive abatements of M. Senard, in proportion as he believed the discovery probable, I promised to exert every effort in my power to effect the desired result. But before any thing could be undertaken, it was necessary that a formal complaint should be made; and M. Senard and the Curè, thereupon, went to Pontoise, and the declaration being consequently made, and the robbery stated, Moiselet was taken up and interrogated. They tried every means to make him confess his guilt; but he persisted in avowing himself innocent, and, for lack of proof to the contrary, the charge was about to be dropped altogether, when to preserve it for a time, I set an agent of mine to work. He, clothed in a military uniform, with his left arm in a sling, went with a billet to the house where Moiselet's wife lived. He was supposed to have just left the hospital, and was only to stay at Livry for forty-eight hours; but a few moments after his arrival, he had a fall, and a pretended sprain suddenly occurred, which put it out of his power to continue his route. It was then indispensable for him to delay, and the mayor decided that he should remain with the cooper's wife until further orders.

The cooper's wife was charmed with his many little attentions. The soldier could write, and became her secretary; but the letters which she addressed to her dear husband were of a nature not to compromise her—not the least expression that can have a twofold construction—it was innocence corresponding with innocence. At length, after a few day's experience, I was convinced that my agent, in spite of his talent, would draw no profit from his mission. I then resolved to manoeuvre in person, and, disguised as a travelling hawker, I began to visit the environs of Livry. I was one of those Jews who deal in every thing,—clothes, jewels, &c. &c.; and I took in exchange gold, silver, jewels, in fact, all that was offered me. An old female robber, who knew the neighbourhood perfectly, accompanied me in my tour: she was the widow of a celebrated thief, Germain Boudier, called Father Latuil, who, after having undergone half-a-dozen sentences, died at last at Saint Pelagie. I flattered myself that Madame Moiselet, seduced by her eloquence, and by our merchandize, would bring out the store of the Curè's crowns, some brilliant of the purest water, nay, even the chalice or paten, in case the bargain should be to her liking. My calculation was not verified; the cooper's wife was in no haste to make a bargain, and her coquetry did not get the better of her.

The Jew hawker was soon metamorphosed into a German servant; and under this disguise I began to ramble about the vicinity of Pontoise, with a design of being apprehended. I sought out the gendarmes, whilst I pretended to avoid them; but they, thinking I wished to get away from them, demanded a sight of my papers. Of course I had none, and they desired me to accompany them to a magistrate, who, knowing nothing of the jargon in which I replied to his questions, desired to know what money I had; and a search was forthwith commenced in his presence. My pockets contained some money and valuables, the possession of which seemed to astonish him. The magistrate, as curious as a commissary, wished to know how they came into my hands; and I sent him to the devil with two or three Teutonic oaths, of the most polished kind; and he, to teach me better manners another time, sent me to prison.

Once more the iron bolts were drawn upon me. At the moment of my arrival, the prisoners were playing in the prison yard, and the jailer introduced me amongst them in these terms, "I bring you a murderer of the parts of speech; understand him if you can."

They immediately flocked about me, and I was accosted with salutations of Landsman and Meinheer without end. During this reception, I looked out for the cooper of Livry.

[He meets with him.]

"Mossié, Mossié," I said, addressing the prisoner, who seemed to think I said Moiselet, "Mossié Fine Hapit, (not knowing his name, I so designated him, because his coat was the colour of flesh,) sacrement, ter teufle, no tongue to me; yer François, I miseraple, I trink vine; faut trink for gelt, plack vine."

I pointed to his hat, which was black; he did not understand me; but on making a gesture that I wanted to drink, he found me perfectly intelligible. All the buttons of my great coat were twenty-franc pieces; I gave him one: he asked if they had brought the wine, and soon afterwards I heard a turnkey say,

"Father Moiselet, I have taken up two bottles for you." The flesh-coloured coat was then Moiselet. I followed him into his room, and we began to drink with all our might. Two other bottles arrived; we only went on in couples. Moiselet, in his capacity of chorister, cooper, sexton, &c. &c. was no less a sot than gossip; he got tipsy with great good-will, and incessantly spoke to me in the jargon I had assumed.

Matters progressed well; after two or three hours such as these I pretended to get stupid. Moiselet, to set me to rights, gave me a cup of coffee without sugar; after coffee came glasses of water. No one can conceive the care which my new friend took of me; but when drunkenness is of such a nature it is like death—all care is useless. Drunkenness overpowered me. I went to bed and slept; at least Moiselet thought so; but I saw him many times fill my glass and his own, and gulp them both down. The next day, when I awoke, he paid me the balance, three francs and fifty centimes, which, according to him, remained from the twenty-franc piece. I was an excellent companion; Moiselet found me so, and never quitted me. I finished the twenty-franc piece with him, and then produced one of forty francs, which vanished as quickly. When he saw it drunk out also he feared it was the last.

"Your button again," said he to me, in a tone of extreme anxiety, and yet very comical.

I showed him another coin. "Ah, your large button again," he shouted out, jumping for joy.

This button went the same way as all the other buttons, until at length, by dint of drinking together, Moiselet understood and spoke my language almost as well as I did myself, and we could then disclose our troubles to each other. Moiselet was very curious to know my history, and that which I trumped up was exactly adapted to inspire the confidence I wished to create.

"My master and I come to France—I was tomestic—master of mein Austrian marechal—Austrian with de gelt in family. Master always roving, always gay, joint regiment at Montreau. Montreau, oh, mein Gott, great, great pattle—many sleep no more but in death. Napoleon coom—poum, poum go gannon. Prusse, Austrian, Rousse all disturb. I, too, much disturb. Go on my ways with master mein, with my havresac on mein horse—poor teufel was I—but there was gelt in it. Master mein say, 'Galop, Fritz.' I called Fritz in home mein. Fritz galop to Pondi—there halt Fritz—place havresac not visible; and if I get again to Yarmany with havresac, me rich becomen, mistress mein rich, father mein rich, you too rich."

Although the narrative was not the cleverest in the world, father Moiselet swallowed it all as gospel; he saw well that during the battle of Montereau, I had fled with my master's portmanteau, and hidden it in the forest of Bondy. The confidence did not astonish him, and had the effect of acquiring for me an increase of his affection. This augmentation of friendship, after a confession which exposed me as a thief, proved to me that he had an accommodating conscience. I thenceforth remained convinced that he knew better than any other person what had become of the diamonds of M. Senard, and that it only depended on him to give me full and accurate information.

One evening, after a good dinner, I was boasting to him of the delicacies of the Rhine: he heaved a deep sigh, and then asked me if there was good wine in that country.

"Yes, yes," I answered, "goot vine and charming girl."

"Charming girl too!"

"Ya, ya."

"Landsman, shall I go with you."

"Ya, ya, me grat content."

"Ah, you content, well! I quit France, yield the old woman, (he showed me by his fingers that Madame Moiselet was three-and-thirty,) and in your land I take little girl no more as fifteen years."

"Ya, bien, a girl no infant: a! you is a brave lad."

Moiselet returned more than once to his project of emigration; he thought seriously of it, but to emigrate liberty was requisite, and they were not inclined to let us go out. I suggested to him that he should escape with me on the first opportunity—and when he had promised me that we would not separate, not even to take a last adieu of his wife, I was certain that I should soon have him in my toils. This certainly was the result of very simple reasoning. Moiselet, said I to myself, will follow me to Germany: people do not travel or live on air: he relies on living well there: he is old, and, like king Solomon, proposes to tickle his fancy with some little Abishag of Sunem. Oh, father Moiselet has found the black hen; here he has no money, therefore his black hen is not here; but where is she? We shall soon learn, for we are to be henceforward inseparable.

As soon as my man had made all his reflections, and that, with his head full of his castles in Germany, he had so soon resolved to expatriate himself, I addressed to the king's attorney-general a letter, in which, making myself known as the superior agent of the Police de Sûreté, I begged him to give an order that I should be sent away with Moiselet, he to go to Livry, and I to Paris.