полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 369, May 9, 1829

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 13, No. 369, May 9, 1829

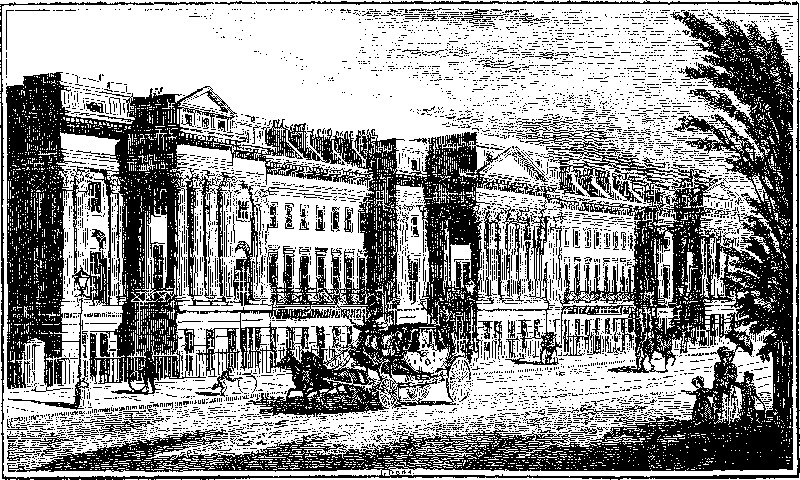

CORNWALL TERRACE REGENT'S PARK

Adjoining York Terrace, engraved and described in No. 358, of the MIRROR, is Cornwall Terrace, one of the earliest and most admired of all the buildings in the Park; although its good taste has not been so influential as might have been expected, on more recent structures. It is named after the ducal title of the present King, when Regent.

Cornwall Terrace is from the designs of Mr. Decimus Burton, and is characterized by its regularity and beauty, so as to reflect high credit on the taste and talent of the young architect. The ground story is rusticated, and the principal stories are of the Corinthian order, with fluted shafts, well proportioned capitals, and an entablature of equal merit. The other embellishments of Cornwall Terrace are in correspondent taste, and the whole presents a facade of great architectural beauty and elegance.

THE COSMOPOLITE

THE TIMES NEWSPAPER

(Concluded from page 292.)

Passing over the leading articles, and some news from the seat of war, next is the Court Circular, describing the mechanism of royal and noble etiquette in right courtly style. The "Money Market and City Intelligence"—what a line for the capitalist: only watch the intensity with which he devours every line of the oracle, as the ancients did the spirantia exta—and weighs and considers its import and bearing with the Foreign News and leading articles. What rivets are these—"risen about 1/4 per cent"—and "a shade higher;" no fag or tyro ever hailed an illustration with greater interest. Talk to him whilst he is reading any other part of the paper, and he will break off, and join you; but when reading this, he can only spare you an occasional "hem," or "indeed"—his eyes still riveted to the column. This has been satirically termed "watching the turn of the market;" although every reader does the same, and first looks for those events in the paper which bear upon his interests or enjoyments; for pleasure, as well as industry, has her studies. Thus the lines "Drury Lane Theatre," and "Professional Concert" are 'Change news to a certain class—and a long criticism on Miss Phillips's first appearance in Jane Shore will ensure attention and sympathy, from anxiety for an actress of high promise, and the pathos of the play itself; and we need not insist upon the beneficial effect which sound criticism has on public taste. To pass from an account of a Concert at the Argyll Rooms, with its fantasias and concertanti, to the fact of 940 weavers being at present unemployed in Paisley,—and the death of a young man in Paris, from hydrophobia, is a sad transition from gay to grave—yet so they stand in the column. A long correspondence on Commercial Policy, Taxation, Finance, and Currency—we leave to the capitalist, the "parliament man," and other disciples of Adam Smith; whilst our eye descends to the right-hand corner, where is recorded the horrible fact of a mother attempting to suffocate her infant at her breast! Humanity sickens at such a pitch of savage crime in the centre of the most refined city in the world!

The commencement of the third folio is a gratifying contrast to the last horrible incident. It describes the Anniversary of St. Patrick's Charity Schools, with one of the King's brothers presiding at the benevolent banquet, and records an after-dinner subscription of 540l.! What a delightful scene for the philanthropist—what a blessed picture of British beneficence! Yet beneath this is a piracy—a tale of blood, whose very recital "will harrow up thy soul"—the murder of the captain and crew of an American brig, as narrated by one man who was concealed. In the next column are two reports of Parish Elections, which afford more speculation than we are prone to indulge, as the turning-out of old parties and setting-up of new, and many of the petty feuds and jealousies that divide and distract parishes or large families, the little circles of the great whole. At the foot of this column a paragraph records the death of a miserly bachelor schoolmaster, who had worn the same coat twenty years, and on the tester of whose bed were found, wrapped up in old stockings £1,600. in interest notes, commencing thirty-five years since, the compound interest of which would have been £4,000.; and for what purpose was this concealment?—a dread of being required to assist his relatives! Yet contrast this wicked abuse with a few of the incidents we have recorded—the dinner of St. Patrick's, for instance, and is it possible to conceive a more despicable situation (short of crime) than this poor miser deserves in our chronicle.

The third column opens to us a scene of a very opposite character, the Newmarket Craven Meeting—the most brilliant assemblage ever known there; the town crammed with the children of chance, the innkeepers trebling their charges, and like the Doncaster people, doing "noting widout the guinea." What an heterogeneous mixture of fine old sport, black legs and consciences, panting steeds and hearts bursting with expectation and despair, and the grand machinery of chance working with mathematical truth, and not unfrequently beneath luxury and the mere show of hospitality.

The moralist will turn away from this rural pandemonium with disgust; but what will he say to the records of wretchedness and crime that fill up nearly the remainder of the folio. A Coroner's Inquest upon a fellow creature who "died from neglect, and want of common food to support life"—and another upon a poor girl, whose young and tender wits being "turned to folly,"—died by a draught of laudanum—are still more lamentable items in the calendar.

Beneath these inquests is a brief tale of a romantic robbery in an obscure department of France. The priest of a village, aged 80, lived in an isolated cottage with his niece. About midnight, he was disturbed, and on his getting out of bed, was bound by two men, whilst a third stood at the door. The robbers then proceeded to the girl's chamber, very ungallantly took her gold ear-rings, and by threatening her and her uncle with death, got possession of 300 francs. Two of the ruffians then proceeded to the church, broke open the poor-box, and took about 30 francs. They then bound again the old man and his niece, and departed. One of the robbers, however, left an agricultural tool behind him, which led to the discovery of two of the thieves, who are committed for trial. This is a perfect newspaper gem.

The fifth column has terror in its first line "Law Report," and commences with an action in the Court of King's Bench, against the late Sheriffs of London for an illegal seizure—one of the glorious delights of office. The next portion relates to an illustrious foreigner, who stated that he professed to swallow fire and molten lead, "but he only put them into his mouth, and took them out again in a sly manner, for they were too hot to eat." (Much laughter.) He could swallow prussic acid without experiencing any ill effects from it; that was what he called pyrotechny; "he had no property except a wife and child, &c."

Next are the Police Reports, sometimes affording admirable studies of men and manners. The first is a case of a man being locked up for the night in a watch-house, "on suspicion of ringing a bell"—and brings to light a most outrageous abuse of petty power. In another case, a gang of robbers pursued by one set of watchmen, were suffered to escape by another set, who would not stir a foot beyond their own boundary line! Neither Shakspeare, Fielding, nor Sheridan have given us a better standing jest than this incident affords. It reminds us of the fellow who refused to take off Tom Ashe's coat, because it was felony to strip an ash; or the tanner who would not help the exciseman out of his pit without twelve hours' notice.

The Births, Marriages, and Deaths—and the Markets, and Price of Stocks, in small type, which well bespeaks their crowded interest, wind up the sheet. Yet what thrilling sensations does this small portion of our sheet often impart. What hopes and expectations for heirs and legacy hunters—people who want the "quotation" of Mark Lane and the Coal Market—and others whose daily tone and temper depends on the little cramped fractions in the "Stocks" and "Funds." Another catches a fine frenzy from the "Shares," and regulates his day's movements "the very air o' the time" by their import—and hence he dreams of gold and gossamer, or sits torturing his imagination with writs and executions that await adverse fortune.

Such are but a few of the pleasures and pains of a newspaper. Shenstone says the first part which an ill-natured man examines, is the list of bankrupts, and the bills of mortality; but, to prove that our object is any thing but ill-natured, we have glanced last at the Deaths. The paper over which we have been travelling, wants the Gazette and Parliamentary News, and a Literary feature. The Debates would have enabled us to illustrate the rapid marches of science and intellect in our times, as displayed in the present perfect system of parliamentary reporting. But enough has been said on other points to prove that the physiognomy of a newspaper is a subject of intense interest. In this slight sketch we have neither magnified the crimes, nor sported with the weaknesses; all our aim has been to search out points or pivots upon which the reflective reader may turn; the result will depend on his own frame of mind.

There is, however, one little paragraph, one pearl appended to the Police Report which we must detach, viz. the acknowledgment of £2. sent to the Bow Street office poor-box, the seventh contribution of the same amount of a benevolent individual (by the handwriting, a lady) signed "A friend to the unfortunate."

Read this ye who gloat over ill-gotten wealth, or abuse good fortune; think of the delights of this divine benefactress—silent and unknown—but, above all, of the exceeding great reward laid up for her in heaven.

PHILO.CAT AND FIDDLE

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

Your correspondent, double X has furnished us with a well written and whimsical derivation of the above ale-house sign, and partly by Roman patriotism and French "lingo," he traces it up to "l'hostelle du Caton fidelle." But I presume the article is throughout intended for pure banter—as I do not consider your facetious friend seriously meant that "no two objects in the world have less to do with each other than a cat and violin."

How close the connexion is between fiddle and cat-gut, seems pretty well evident—for a proof, I therefore refer double X to any cat-gut scraper in his majesty's dominions, from the theatres royal, to Mistress Morgan's two-penny hop at Greenwich Fair.

JACOBUS.THE ROUE'S INTERPRETATION OF DEATH

(For the Mirror.)

"Death! who would think that five simple letters, would produce a word with so much terror in it."—The Rou.

Death! and why should it beThat hideous mysteryIs with those atoms integral combin'd?Alas! too well—too well,I've prob'd unto the spellIn each dark imag'd sound, that lurks entwin'd!Eternity, impliedIn Death, and long deniedNow sacrifices my tortur'd menial gaze!Whilst, with its lurid lightHeart-burnings fierce uniteAnd what may quench, the guilty spirit's blaze?Annihilation!—this,Was once, the startling blissI forc'd my soul to fancy Death should give!But, whilst I shudd'ring blessThe hopes—of—nothingness,A something sighs: "Beyond the grave I live!"Tophet! I thrill! for scorn'dWas the sere thought, though warn'dOfttimes that Death, enclos'd that dread abyss!Now, by each burning veinAnd venom'd conscience—painI know the terrors of that world, in this!Heaven! ay, 'tis in DeathFor him, whose fragile breathWends from a breast of piety and peace,But darkness, chains, and dreeEternal, are for meSince Death's tremendous myst'ries never cease!M.L.B.TO JUDY

(For the Mirror.)

I have thought of you much since we parted,And wished for you every day,And often the sad tear has started,And often I've brush'd it away;When the thought of thy sweet smile come o'er meLike a sunbeam the tempest between,And the hope of thy love shone before meSo brilliantly bright and serene,I remember thy last vow that made meForget all my sorrow and care,And I think of the dear voice that bade meAwake from the dream of despair.I regard not the gay scene around me,The smiles of the young and the free,Have not now the soft charm that once bound me.For that hath been broken by thee;And tho' voices, dear voices are teeming,With friendship and gladness, and wit,And a welcome from bright eyes is beaming,I cannot, I cannot, forget—I may join in the dance and the song,And laugh with the witty and gay,Yet the heart and best feelings that throngAround it, are far, far away.Dost remember the scene we last traced, love,When the smile from night's radiant queenBeamed bright o'er the valley, and chased loveThe spirit of gloom from the scene?And the riv'let how heedless it rushed, love,From its home in the mountain away,And the wild rose how faintly it blush'd, love,In the light of the moon's silver ray:Oh, that streamlet was like unto me,Parting from whence its brightness first sprung,And that sweet rose was the emblem of thee,As so pale on my bosom you hung.Dearest, why did I leave thee behind me,Oh! why did I leave thee at all,Ev'ry day that dawns, only can find meIn sorrow, and tho' the sweet thrallOf my heart serves to cheer and to check meWhen sorrow or passion have sway,Yet I'd rather have thee to hen-peck1 me,Than be from thy bower away;And, dear Judy, I'm still what you found me,When we met in the grove by the rill,I forget not the spell that first bound me,And I shall not, till feeling be still.F. BERINGTON.ANCIENT PLACES OF SANCTUARY IN LONDON AND WESTMINSTER

"No place indeed should murder sanctuarise."SHAKSPEARE.The principal sanctuaries were those in the neighbourhood of Fleet-street, Salisbury-court, White Friars, Ram-alley, and Mitre-court; Fulwood's-rents, in Holborn, Baldwin's-gardens, in Gray's-inn-lane; the Savoy, in the Strand; Montague-close, Deadman's-place, the Clink, the Mint, and Westminster. The sanctuary in the latter place was a structure of immense strength. Dr. Stutely, who wrote about the year 1724, saw it standing, and says that it was with very great difficulty that it was demolished. The church belonging to it was in the shape of a cross, and double, one being built over the other. It is supposed to have been built by Edward the Confessor. Within this sanctuary was born Edward V., and here his unhappy mother took refuge with her son, the young Duke of York, to secure him from the villanous proceedings of his cruel uncle, the Duke of Gloucester, who had possession of his elder brother. The metropolis at one time (says the Rev. Joseph Nightingale,) abounded with these haunts of villany and wretchedness. They were originally instituted for the most humane and pious purposes; and owe their origin to one of the sacred institutions of the Mosaic law, which appointed certain cities of refuge for persons who had accidentally slain any of their fellow creatures. The institution, as Marmonides justly observes, was a merciful provision both for the manslayer, that he might be preserved, and for the avenger, that his blood might be cooled by the removal of the manslayer out of his sight. In the year 1487, during the Pontificate of Innocent VIII. a bull was issued, and sent here, to lay a little restraint on the privileges of sanctuary. It stated, that if thieves, murderers, or robbers, registered as sanctuary-men, should sally out and commit fresh nuisances, which they frequently did, and enter again, in such cases they might be taken out of their sanctuaries by the king's officers. That as for debtors, who had taken sanctuary to defraud their creditors, their persons only should be protected; but their goods out of sanctuary, should be liable to seizure. As for traitors, the king was allowed to appoint them keepers in their sanctuaries, to prevent their escape. After the Reformation had gained strength, these places of sanctuary began to sink into contempt, and in the year 1697, it became absolutely necessary to take some legislative measures for their destruction.

P.T.W.TRUE PHILOSOPHY

A footman who had been found guilty of murdering his fellow-servant, was engaged in writing his confession: "I murd—" he stopped, and asked, "How do you spell murdered?"

THE SELECTOR AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

TIMBER TREES

In the last volume of the MIRROR, we gave several extracts from a delightful paper on Landscape Gardening, contained in a recent Number of the Quarterly Review; with an abstract of Sir Henry Steuart's new method of transplanting trees, and a variety of information on this interesting department of rural economy. We are therefore pleased to see that the Society for the diffusion of Useful Knowledge, have appropriated the second part of their new work to what are termed "Timber Trees and their applications;" and probably few of their announced volumes will exceed in usefulness and entertainment that which is now before us. Indeed, the Editor could scarcely have devised a more successful means of impressing his readers with a sincere love of nature and her sublime works, than by introducing them to the history of vegetable substances in their connexion with the useful arts.

We subjoin a few specimens, with occasional notes, arising from our own reading and personal observation.

Picturesque Beauty of the OakA fine oak is one of the most picturesque of Trees. It conveys to the mind associations of strength and duration, which are very impressive. The oak stands up against the blast, and does not take, like other trees, a twisted form from the action of the winds. Except the cedar of Lebanon, no tree is so remarkable for the stoutness of its limbs: they do not exactly spring from the trunk, but divide from it; and thus it is sometimes difficult to know which is stem and which is branch. The twisted branches of the oak, too, add greatly to its beauty; and the horizontal direction of its boughs, spreading over a large surface, completes the idea of its sovereignty over all the trees of the forest. Even a decayed oak,—

"–dry and dead,Still clad with reliques of its trophies old,Lifting to heaven its aged hoary head,Whose foot on earth Hath got but feeble hold—"—even such a tree as Spenser has thus described is strikingly beautiful: decay in this case looks pleasing. To such an oak Lucan compared Pompey in his declining state.

The CedarThe cedar of Lebanon, though it has been introduced into many parts of England as an ornamental tree, and has thriven well, has not yet been planted in great numbers for the sake of its timber. No doubt it is more difficult to rear, and requires a far richer soil than the pine and the larch; but the principal objection to it has been the supposed slowness of its growth, although that does not appear to be very much greater than in the oak. Some cedars, which have been planted in a soil well adapted to them, at Lord Carnarvon's, at Highclere, have grown with extraordinary rapidity. Of the cedars planted in the royal garden at Chelsea, in 1683, two had, in eighty-three years, acquired a circumference of more than twelve feet, at two feet from the ground, while their branches increased over a circular space forty feet in diameter. Seven-and-twenty years afterwards the trunk of the largest one had extended more than half a foot in circumference; which is probably more than most oaks of a similar age would do during an equal period. The surface soil in which the Chelsea cedars throve so well is not by any means rich; but they seem to have been greatly nourished from a neighbouring pond, upon the filling up of which they wasted away.

Various specimens of the cedar of Lebanon are mentioned as having attained a very great size in England. One planted by Dr. Uvedale, in the garden of the manor-house at Enfield, about the middle of the seventeenth century, had a girth of fourteen feet in 1789; eight feet of the top of it had been blown down by the great hurricane in 1703, but still it was forty feet in height. At Whitton, in Middlesex, a remarkable cedar was blown down in 1779. It had attained the height of seventy feet; the branches covered an area one hundred feet in diameter; the trunk was sixteen feet in circumference at seven feet from the ground, and twenty-one feet at the insertion of the great branches twelve feet above the surface. There were about ten principal branches or limbs, and their average circumference was twelve feet. About the age and planter of this immense tree its historians are not agreed, some of them referring its origin to the days of Elizabeth, and even alleging that it was planted by her own hand. Another cedar, at Hillingdon, near Uxbridge, had, at the presumed age of 116 years, arrived at the following dimensions; its height was fifty-three feet, and the spread of the branches ninety-six feet from east to west, and eighty-nine from north to south. The circumference of the trunk, close to the ground, was thirteen feet and a half; at seven feet it was twelve and a half; and at thirteen feet, just under the branches, it was fifteen feet eight inches. There were two principal branches, the one twelve feet and the other ten feet in girth. The first, after a length of eighteen inches, divided into two arms, one eight feet and a half, and the other seven feet ten. The other branch, soon after its insertion, was parted into two, of five feet and a half each.2

The Yew Tree(Called Taxus, probably from the Greek, which signifies swiftness, and may allude to the velocity of an arrow shot from a yew-tree bow,) is a tree of no little celebrity, both in the military and the superstitious history of England. The common yew is a native of Europe, of North America, and of the Japanese Isles. It used to be very plentiful in England and Ireland, and probably also Scotland. Caesar mentions it as having been abundant in Gaul; and much of it is found in Ireland, imbedded in the earth. The trunk and branches grow very straight; the bark is cast annually; and the wood is compact, hard, and very elastic. It is therefore of great use in every branch of the arts in which firm and durable timber is required; and, before the general use of fire-arms, it was in high request for bows: so much of it was required for the latter purpose, that ships trading to Venice were obliged to bring ten bow staves along with every butt of Malmsey. The yew was also consecrated—a large tree, or more being in every churchyard; and they were held sacred.3 In funeral processions the branches were carried over the dead by mourners, and thrown under the coffin in the grave. The following extract from the ancient laws of Wales will show the value that was there set upon these trees, and also how the consecrated yew of the priests had risen in value over the reputed sacred mistletoe of the Druids:—

"A consecrated yew, its value is a pound.

"A misletoe branch, threescore pence.

"An oak, sixscore pence.

"Principal branch of an oak, thirty pence.

"A yew tree, (not consecrated) fifteen pence.

"A sweet apple, threescore pence.

"A sour apple, thirty pence.

"A thorn-tree, seven pence halfpenny. Every tree after that, fourpence."

By a statute made in the 5th year of Edward IV., every Englishman, and Irishman dwelling with Englishmen, was directed to have a bow of his own height made of yew, wych-hazel, ash, or awburne—that is, laburnum, which is still styled "awburne saugh," or awburne willow, in many parts of Scotland. His skill in the use of the long bow was the proud distinction of the English yeoman, and it was his boast that none but an Englishman could bend that powerful weapon. It seems that there was a peculiar art in the English use of this bow; for our archers did not employ all their muscular strength in drawing the string with the right hand, but thrust the whole weight of the body into the horns of the bow with the left. Chaucer describes his archer as carrying "a mighty bowe;" and the "cloth-yard shaft," which was discharged from this engine, is often mentioned by our old poets and chroniclers. The command of Richard III. at the battle which was fatal to him, was this: