полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 329, August 30, 1828

Womankind, Mr. Editor, I do not believe, are naturally vain; but as they were made for us and for our comfort, it is natural that they should endeavour to gain our esteem; but they carry their endeavours too far; by straining to excite attention they overstep the mark, become vain and coquetish, one strives to outdo another, others say they must do as other women do, and they thus make themselves ridiculous unknowingly. It is really painful to see a woman of sense and education become a slave to the tyranny of fashion—and injuring both body and mind—and it is, I think, an insult to a man of understanding to endeavour to excite his attention by any such peculiarities.

Having now generally stated the subject that I should wish to be taken up by abler hands than mine, I will conclude by recommending all your town-bred, and coquetish ladies to study and restudy a letter signed "Mary Home," in No. 254 of the excellent work before alluded to, "The Spectator." —H.M—. Great Surrey Street, Aug. 1828.

RETROSPECTIVE GLEANINGS

HISTORICAL ACCOUNT OF SMITHFIELD

(For the Mirror.)Stowe, in his "Survey of London," 1633, says, "Then is Smithfield Pond, which of (old time) in records was called Horsepoole, for that men watered horses there, and was a great water. In the 6th of Henry V. a new building was made in the west part of Smithfield, betwixt the said poole and the river of Wels, or Turne-mill-brooke, in a place then called the Elms, for that there grew many elme-trees, and this had been the place of execution for offenders. Since the which time, the building there hath been so increased, that now remaineth not one tree growing. In the yeere 1357, the 31st of Edward III., great and royall justs were then holden in Smithfield, there being present the kings of England, France, and Scotland, with many other nobles, and great estates of divers lands. In the yeere 1362, the 36th of Edward III., on the first five daies of May, in Smithfield, were justs holden, the king and queene being present, with the most part of the chivalry of England and of France and of other nations; to which came Spaniards, Cyprians, and Armenians, knightly requesting ayde of the king of England against the Pagans, that invaded their confines. The 48th of Edward III., Dame Alice Perrers, or Pierce, (the king's concubine,) as lady of the Sunne, rode from the Tower of London through Cheape, accompanied of many lords and ladies, every lady leading a lord by his horse bridle, till they came into West Smithfield, and then began a great just, which endured seven daies after.—In the 14th of Richard II., royal justs and turnements were proclaimed to be done in Smithfield, to begin on Sunday next, after the feast of Saint Michael; many strangers came forth of other countries, namely, Valarian, Earle of St. Paul, that had married King Richard's sister, the Lady Maud Courtney; and William, the young Earle of Ostervant, son to Albert of Baviere, Earle of Holland and Henault. At the day appointed, there issued forth at the Tower, about the third houre of the day, 60 coursers, apparelled for the justs, upon every one an esquire of honour riding a soft pace; then came forth 60 ladies of honour, mounted upon palfraies, riding on the one side, richly apparelled, and every lady led a knight with a chain of gold; those knights, being on the king's party, had their armour and apparell garnished with white harts, and crownes of gold about the harts' neckes; and so they came riding through the streets of London to Smithfield, with a great number of trumpets, &c. The kinge and the queene, who were lodged in the bishop's palace of London, were come from thence, with many great estates, and placed in chambers, to see the justs. The ladies that led the knights were taken down from their palfraies, and went up to chambers prepared for them. Then alighted the esquires of honour from their coursers, and the knights in good order mounted upon them; and after their helmets were set on their heads, and being ready in all points, proclamation made by the heralds, the justs began, and many commendable courses were runne, to the great pleasure of the beholders. The justs continued many days with great feastings, as ye may reade in Froisard," &c. &c.

Smithfield, says Pennant, "was also the spot on which accusations were decided by duel, derived from the Kamp-fight ordeal of the Saxons. I will only (says Mr. P.) mention an instance. It was when the unfortunate armourer entered into the lists, on account of a false accusation of treason, brought against him by his apprentice, in the reign of Henry VI. The friends of the defendant had so plied him with liquor, that he fell an easy conquest to his accuser. Shakspeare has worked this piece of history into a scene, in the second part of Henry VI., but has made the poor armourer confess his treasons in his dying moments; for in the time in which this custom prevailed, it never was even suspected but that guilt must have been the portion of the vanquished. When people of rank fought with sword and lance, plebeian combatants were only allowed a pole, armed with a heavy sand-bag, with which they were to decide their guilt or innocence. In Smithfield were also held our autos-de-fee; but to the credit of our English monarchs, none were ever known to attend the ceremony. Even Philip II. of Spain never honoured any, of the many which were celebrated by permission of his gentle queen, with his presence, notwithstanding he could behold the roasting of his own subjects with infinite self-applause and sang-froid. The stone marks the spot, in this area, on which those cruel exhibitions were executed. Here our martyr Latimer preached patience to friar Forest, agonizing under the torture of a slow fire, for denying the king's supremacy; and to this place our martyr Cranmer compelled the amiable Edward, by forcing his reluctant hand to the warrant, to send Joan Bocher, a silly woman, to the stake. Yet Latimer never thought of his own conduct in his last moments; nor did Cranmer thrust his hand into the fire for a real crime, but for one which was venial, through the frailty of human nature. Our gracious Elizabeth could likewise burn people for religion. Two Dutchmen, Anabaptists, suffered in this place in 1675, and died, as Holinshed sagely remarks, with "roring and crieing." But let me say, (says Pennant,) that this was the only instance we have of her exerting the blessed prerogative of the writ De Haeretico comburendo. Her highness preferred the halter; her sullen sister faggot and fire. Not that we will deny but Elizabeth made a very free use of the terrible act of her 27th year. One hundred and sixty-eight suffered in her reign, at London, York, in Lancashire, and several other parts of the kingdom, convicted of being priests, of harbouring priests, or of becoming converts. But still there is a balance of 109 against us in the article persecution, and that by the agonizing death of fire; for the smallest number estimated to have suffered under the savage Mary, amounts, in her short reign, to 277. The last person who suffered at the stake in England was Bartholomew Logatt, who was burnt here in 1611, as a blasphemous heretic, according to the sentence pronounced by John King, bishop of London. The bishop consigned him to the secular of our monarch James, who took care to give the sentence full effect. This place, as well as Tybourn, was called The Elms, and used for the execution of malefactors even before the year 1219. In the year 1530, there was a most severe and singular punishment inflicted here on one John Roose, a cook, who had poisoned 17 persons of the Bishop of Rochester's family, two of whom died, and the rest never recovered their health. His design was against the pious prelate Fisher, who at that time resided at Rochesterplace, Lambeth. The villain was acquainted with the cook, and, coming into the bishop's kitchen, took an opportunity, while the cook's back was turned to fetch him some drink, to fling a great quantity of poison into the gruel, which was prepared for dinner for the bishop's family, and the poor of the parish. The good bishop escaped. Fortunately, he that day abstained from food. The humility and temperance of that good man are strongly marked in this relation, for he partook of the same ordinary food with the most wretched pauper. By a retrospective law, Roose was sentenced to be boiled to death, which was done accordingly. In Smithfield, the arch-rebel, Wat Tyler, met with, in 1381, the reward of his treason and insolence."

Smithfield3 is at present celebrated, and long since, for being the great market for cattle of all kinds, and likewise for being the place where Bartholomew fair is held, alias the Cockneys' Saturnalia, which was granted by Henry II. to the neighbouring priory.

P.T.W.

THE ANECDOTE GALLERY

THE ANDALUSIAN ASS

A gay lieutenant of the Spanish Royal Guards, known by the name of Alonzo Beldia, became violently enamoured of the beautiful Carlotta Pena, the eldest daughter of a reputable gunsmith, whose humble habitation adjoined the vast cemetery of Valencia, and whom Beldia had casually seen at a public entertainment given in that good city.

Alonzo was affable and extremely complaisant, though an egotist and somewhat loquacious; but nature had, nevertheless, bestowed upon him a prepossessing exterior with an enviable pair of jet black whiskers, and the most expressive eyes; he could sing a tonadilla divinely; dance the fandango with inimitable grace; and "strike the light guitar" with unparalleled mastery. He was, in truth, an accomplished man of pleasure, and by his gallantry he subdued the tender hearts of many fair daughters of Ferdinand's domains.

On a dark night in the month of December, just as Alonzo had played one of his bewitching airs, with his wonted execution, and was engaged, in converse sweet, with the enraptured Carlotta, an extraordinary and seemingly supernatural noise suddenly proceeded from a distant part of the hallowed ground where Alonzo sacrificed at the shrine of love. Jesu Maria! exclaimed the terrified damsel, what, in the name of heaven, can it be? ere the silvery tones of her sweet voice had reached the ears of the petrified Alonzo, the "iron tongue" of the cathedral clock announced the hour of midnight, and the solemn intonation of its prodigious bell instilled new horrors into the confused minds of the affrighted lovers. The brave, the royal Alonzo heard not the voice of his enchanting dulcinea; he, poor fellow, with difficulty supported his trembling frame against an ancient memento mori, which reared its tristful crest within a whisper of the lattice of the lovely Carlotta. Large globules of transparent liquid adorned his pallid brow, and his convulsed knees sought each other with mechanical solicitude. It was a moment pregnant with the gravest misery to poor Alonzo; not a star was seen to enliven the murky night, and the wind whistled most lugubriously. He was in a state of insensibility, and would have fallen to the cold earth, but luckily for the valiant youth, the melodious voice of the enchanting girl again breathed the tenderest hopes for the safety of her adored Alonzo. He sprang upon his legs and drew a pistol from his girdle, which he discharged with unerring aim at the dreaded goblin. A horrible groan followed this murderous act, which was succeeded by a confused noise, and a solemn silence ensued! "It's vanished, Carlotta! I have hurried the intruding demon to the nether world!" exclaimed the valorous guardsman. "Heavens be praised," cried the superstitious girl, "but hasten, my love—quit this spot directly—my father has alarmed his people—away, away!"

The worthy maker of guns approached the scene of carnage, accompanied by the inmates of his dwelling, with rueful countenances, illumined by tapers, when the cause of their disquietude was soon discovered. No apparition or sprite forsooth, but a full grown donkey of the Andalusian breed, lay weltering in gore, yet warm with partial life! By timely liberality the valorous Alonzo escaped detection, though the heroic deed is still remembered in merry Valencia, and often cited as an instance of glorious (?) chivalry.

GRADIVUS.

SPIRIT OF DISCOVERY

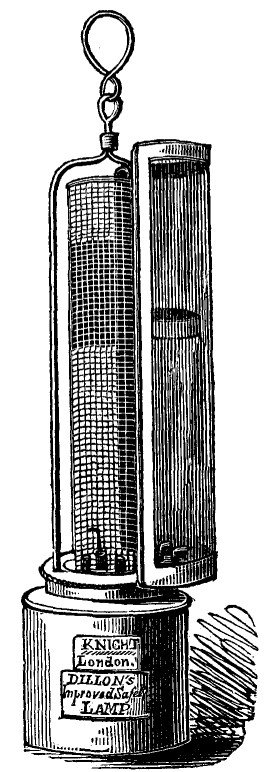

IMPROVED SAFETY LAMP

Mr. Dillon has lately introduced to the notice of the scientific world, an improvement upon the Safety Lamp of Sir Humphry Davy, which appears to us of sufficient interest for illustration in our columns. As the Davy Lamp is too well known to need special description here, it will be merely necessary to allude to the principle of the invention, in order to point out Mr. Dillon's improvement.

He maintains, in opposition to Sir Humphry Davy, that the Davy lamp acts by its heat and rarefaction, and not from Sir H. Davy's theory, that flame is cooled by a wire-gauze covering. He shows, by a simple experiment, that the Davy lamp is not safe in a current of hydrogen or carburetted hydrogen gas, and that many lives may have been lost from the confidence of miners in its perfect safety. A current of hydrogen or carburetted hydrogen gas steadily directed on the flame of the lamp from a bladder and stopcock, by cooling the wire gauze, brings the flame of the lamp through the gauze to the mouth of the stopcock, (even should there be six folds of gauze intervening.) He shows also, by immersing the lamp, when cold and newly lighted, into a jar of dense hydrogen or carburetted hydrogen gas, or an explosive mixture with atmospheric air, that explosion takes place inside and outside of the lamp; whereas, when the lamp has burnt sufficiently long to heat the wire gauze, no explosion takes place on the outside of the lamp. These experiments appear incontrovertible in support of his theory, which is, "that the wire gauze is merely the rapid receiver and the retainer of heat, and that it is the caloric in its meshes which prevents the flame of the lamp from being fed by the oxygen of the atmosphere on the outside."

The experiments of Libri, showing that flame is inflected by metallic rods, and that "when two flames are made to approach each other, there is a mutual repulsion, although their proximity increases the temperature of each, instead of diminishing it," support Mr. Dillon's theory—the inflection being occasioned by the rarefaction of the air between the rod and the flame, the latter seeking for oxygen to support it in a denser medium, the two flames repelling each other for the same reason, and not from any mysterious and "repulsive effect of the wires of the gauze tissue." Mr. Dillon increases the heat of the lamp, and places on it a shield of talc to protect it from a current, and, upon his theory, the shafts or workings of iron and coal mines may be lighted with gas with perfect safety, protecting the flame with wire gauze and a circular shield of talc.

EPITAPH ON A FRENCH SCOLD

Ci git ma femme; ah! qu'il est bienPour son repos et pour le mien.THE SELECTOR; AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

PENELOPE, OR LOVE'S LABOUR LOST

This is one of the most deservedly attractive novels of the past season; and the good sense with which it abounds, ought to insure it extensive circulation. It has none of the affectation or presumptuousness of "fashionable" literature; but is at once a rational picture of that order of society to which its characters belong, and a just satire on the superior vices of the wealthy and the great. The author is evidently no servile respecter of either of the latter classes, for which reason, his work is the more estimable, and is a picture of real life, whereas fashion at best lends but a disguise, or artificial colouring to the actions of men, and thus renders them the less important to the world, and less to be depended on as scenes and portraitures of human character. The former will, however, stand as lasting records of the men and manners of the age in which they were drawn, whilst the latter, being in their own day but caricatures of life, will, in course of time, fade and lose their interest, and at length become levelled with the mere ephemera, or day-flies of literature. It is true that novel-writing has, within the last sixteen, or eighteen years, attained a much higher rank than it hitherto enjoyed; but it should be remembered that this superiority has not been grounded in mawkish records of the fashionable follies of high life, such as my Lord Duke, or my Lady Bab, might indite below stairs, for the amusement of those in the drawing-room; on the contrary, it was founded in portraits and pictures of human nature, strengthened by historical, or matter-of-fact interest, and stripped of the trickery of fancy and romance; whereas, the chronicles of fashion are little better than the vagaries of an eccentric few, who bear the same proportion to the general mass of society, that the princes, heroes, and statesmen of history do to the whole world. This is a fallacy of which thousands of Bath and Cheltenham novel-readers are not yet aware, and which the listless Dangles of Brighton and Margate have yet to learn, ere they can hope to arrive at a correct estimate of human nature; but to such readers we cordially recommend Penelope as the best corrective we can prescribe for the bile of fashionable prejudice, or the nausea arising from overstrained fiction, modified as it is to the romance of real life.

Penelope has, however, one of the failings common to fashionable novels. Its plot is weak and meagre—but it is still simple and natural, and has not borrowed any of those adventitious aids to which we have alluded above. It bears throughout an air of probability, untinctured by romance, and has the strong impress of truth and fidelity to nature. Sketchy and vivacious, always humorous and sometimes witty; it has many scenes and portraits, which in terseness and energy, will compare with any of its predecessors; and occasionally there are touches of genuine sentiment which seize on the sympathies of the reader with more than common effect. The incidents of the narrative do not present many opportunities for these displays of the writer's talent, and we cannot refrain from thinking that their more frequent introduction would have increased the success of the work—that is, if we may be allowed to judge from the specimens with which the author has here favoured us.

But we are getting somewhat too critical, and consequently as much out of our element as modern aeronauts, who are no sooner in the air than they seem to think of their descent. We shall not, however, impair the pleasure of the reader by giving him a foretaste of the whole plot of Penelope; but we shall rather confine ourselves to a few portrait-specimens of characters, whose drawing will, we hope, attract the general reader; presuming, as we do, that its claims to his attention will be found to outweigh dozens of the scandalous chronicles of high fashion. We are not told whether the parties ate with silver or steel forks, or burned wax or tallow; but those characters must be indeed poorly drawn which do not enable the reader to satisfy himself about such trifles, allowing that he thinks them worth his study.

An outline of the characters may not be unacceptable. The scene lies principally in the villages of Neverden and Smatterton; and between their rectors Dr. Greendale and Mr. Darnley, and their families; the Earl of Smatterton, of Smatterton Hall; Lord Spoonbill, his son; Sir George Aimwell, of Neverden Hall; Penelope Primrose, the heroine, who is placed by her father under the care of Dr. Greendale, whilst Mr. Primrose seeks to repair his fortune in the Indies; and Robert Darnley, Penelope's suitor, also for sometime in the Indies, who is thwarted in his views by Lord Spoonbill, and a creature named colonel Crop, &c.

In the early part of the narrative, Dr. Greendale dies, and Penelope is removed from Smatterton to London, where she is to be brought out as a singer, under the patronage of the Countess of Smatterton, and Spoonbill is first struck with her charms, and resolves to frustrate his absent rival.

The roguery of a postboy named Nick Muggins, who is employed by the noble suitor to intercept letters, and the aid of Crop, who acts as a sort of go-between, are put in requisition for this purpose; but the villany of the latter is finely defeated in his mistaking a silly, forward girl, Miss Glossop, for Penelope, and accordingly prevailing on her to elope with him to Lord Spoonbill's villa, where the blunder is soon discovered by his lordship, who in return is horsewhipped by the father of Miss Glossop; and Darnley and Penelope are eventually married.

There are two or three adjuncts, as Peter Kipperson, a "march of intellect" man, Erpingham, one of Spoonbill's companions in debauchery, Ellen Fitzpatrick, one of his victims, Dr. Greendale's successor, Charles Pringle; and Zephaniah Pringle, a literary coxcomb of the first order.

The portrait of Dr. Greendale is of high finish—full of the truth and amiability of the Christian character—one who regarded the false distinctions of society in their proper light, and knew how to set a right value upon the influence of good example, and who was "loved and respected for the steadiness and respectability of his character; for the integrity, purity, simplicity, and sincerity of his life." At the same time, the doctor is finely contrasted with his wife, who possessed the common failing of paying homage to her illustrious neighbours to obtain their notice and patronage, and who felt flattered by a collateral branch of the Smattertons accepting an invitation to her table. Of the heroine, we quote the author's outline:—

Penelope Primrose exceeded the middle stature, that her dark blue eyes were shaded by a deep and graceful fringe, that her complexion was somewhat too pale for beauty, but that its paleness was not perceptible as a defect whenever a smile illumined her countenance, and developed the dimples that lurked in her cheek and underlip. Her features were regular, her gait exceedingly graceful, and her voice musical in the highest degree. Seldom, indeed, would she indulge in the pleasure of vocal music, but when she did, as was sometimes the case to please the Countess of Smatterton, her ladyship, who was a most excellent judge, used invariably to pronounce Miss Primrose as the finest and purest singer that she had ever heard.

The character of Lord Spoonbill is struck out with singular felicity and spirit:—

Lord Spoonbill was not one of those careless young men who lose at the university what they have gained at school; one reason was, that he had little or nothing to lose; nor was his lordship one of those foolish people who go to a university and study hard to acquire languages which they never use, and sciences which they never apply in after-life. His lordship had sense enough to conclude that, as the nobility do not talk Greek, he had no occasion to learn it; and as hereditary legislators have nothing to do with the exact sciences, it would be a piece of idle impertinence in him to study mathematics. But his lordship had heard that hereditary legislators did occasionally indulge in other pursuits, and for those pursuits he took especial care to qualify himself. In his lordship's cranium, the organ of exclusiveness was strongly developed. We do not mean that his head was so constructed internally, as to exclude all useful furniture, but that he had a strong sense of the grandeur of nobility and the inseparable dignity which attaches itself to the privileged orders. The only instances in which he condescended to persons in inferior rank, were when he was engaged at the race-course at Newmarket, or when he found that condescension might enable him to fleece some play-loving plebeian, or when affairs of gallantry were concerned. In these matters no one could be more condescending than Lord Spoonbill. We should leave but an imperfect impression on the minds of our readers if we should omit to speak of his lordship's outward and visible form. This was an essential part of himself which he never neglected or forgot; and it should not be neglected or forgotten by his historian. He was tall and slender, his face was long, pale and thin, his forehead was narrow, his eyes large and dull, his nose aquiline, his mouth wide, his teeth beautifully white and well formed, and displayed far more liberally than many exhibitions in the metropolis which are only "open from ten till dusk." His lips were thin, but his whiskers were tremendously thick. Of his person he was naturally and justly proud. Who ever possessed such a person and was not proud of it?