полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 10, No. 280, October 27, 1827

"I am ashamed to look no man in the face," said Robin Oig, something moved; "and, moreover, I will look you in the face this blessed day, if you will bide at the Clachan down yonder."

"Mayhap you had as well keep away," said his comrade; and turning his back on his former friend, he collected his unwilling associates, assisted by the bailiff, who took some real and some affected interest in seeing Wakefield accommodated.

After spending some time in negotiating with more than one of the neighbouring farmers, who could not, or would not, afford the accommodation desired, Henry Wakefield, at last, and in his necessity, accomplished his point by means of the landlord of the alehouse at which Robin Oig and he had agreed to pass the night, when they first separated from each other. Mine host was content to let him turn his cattle on a piece of barren moor, at a price little less than the bailiff had asked for the disputed enclosure; and the wretchedness of the pasture, as well as the price paid for it, were set down as exaggerations of the breach of faith and friendship of his Scottish crony. This turn of Wakefield's passions was encouraged by the bailiff (who had his own reasons for being offended against poor Robin, as having been the unwitting cause of his falling into disgrace with his master), as well as by the innkeper, and two or three chance guests, who soothed the drover in his resentment against his quondam associate,—some from the ancient grudge against the Scots, which, when it exists any where, is to be found lurking in the Border counties, and some from the general love of mischief, which characterizes mankind in all ranks of life, to the honour of Adam's children be it spoken. Good John Barleycorn also, who always heightens and exaggerates the prevailing passions, be they angry or kindly, was not wanting in his offices on this occasion; and confusion to false friends and hard masters, was pledged in more than one tankard.

In the meanwhile, Mr. Ireby found some amusement in detaining the northern drover at his ancient hall. He caused a cold round of beef to be placed before the Scot in the butler's pantry, together with a foaming tankard of home-brewed, and took pleasure in seeing the hearty appetite with which these unwonted edibles were discussed by Robin Oig M'Combich. The squire himself lighting his pipe, compounded between his patrician dignity and his love of agricultural gossip, by walking up and down while he conversed with his guest.

"I passed another drove," said the squire, with one of your countrymen behind them, they were something less beasts than your drove—doddies most of them; a big man was with them—none of your kilts though, but a decent pair of breeches;—d'ye know who he may be?"

"Hout ay—that might, could, and would pe Hughie Morrison—I didna think he could hae peen sae weel up. He has made a day on us; put his Argyle-shires will have wearied shanks. How far was he pehind?"

"I think about six or seven miles," answered the squire, "for I passed them at the Christenbury Cragg, and I overtook you at the Hollan Bush. If his beasts be leg-weary, he will be may be selling bargains."

"Na, na, Hughie Morrison is no the man for pargains—ye maun come to some Highland body like Robin Oig hersell for the like of these;—put I maun be wishing you good night, and twenty of them, let alane ane, and I maun down to the Clachan to see if the lad Henry Waakfelt is out of his humdudgeons yet."

The party at the alehouse were still in full talk, and the treachery of Robin Oig still the theme of conversation, when the supposed culprit entered the apartment. His arrival, as usually happens in such a case, put an instant stop to the discussion of which he had furnished the subject, and he was received by the company assembled with that chilling silence, which more than a thousand exclamations tells an intruder that he is unwelcome. Surprised and offended, but not appalled by the reception which he experienced, Robin entered with an undaunted, and even a haughty air, attempted no greeting as he saw he was received with none, and placed himself by the side of the fire, a little apart from a table, at which Harry Wakefield, the bailiff, and two or three other persons, were seated. The ample Cumbrian kitchen would have afforded plenty of room even for a larger separation.

Robin, thus seated, proceeded to light his pipe, and call for a pint of twopenny.

"We have no twopenny ale," answered Ralph Heskett, the landlord; but as thou find'st thy own tobacco, its like thou may'st find thine own liquor too—it's the wont of thy country, I wot."

"Shame, goodman," said the landlady, a blithe, bustling housewife, hastening herself to suply the guest with liquor—"Thou knowest well enow what the strange man wants, and it's thy trade to be a civil man. Thou shouldest know, that if the Scot likes a small pot, he pays a sure penny."

Without taking any notice of this nuptial dialogue, the Highlander took the flagon in his hand, and, addressing the company generally, drank the interesting toast of "Good markets," to the party assembled.

"The better that the wind blew fewer dealers from the north," said one of the farmers, and fewer Highland runts to eat up the English meadows."

"Soul of my pody, put you are wrang there, my friend," answered Robin, with composure, "it is your fat Englishmen that eat up our Scots cattle, puir things."

"I wish there was a summat to eat up their drovers," said another; "a plain Englishman canna make bread within a kenning of them."

"Or an honest servant keep his master's favour, but they will come sliding in between him and the sunshine," said the bailiff.

"If these pe jokes," said Robin Oig, with the same composure, "there is ower mony jokes upon one man."

"It is no joke, but downright earnest," said the bailiff. "Harkye, Mr. Robin Ogg, or whatever is your name, it's right we should tell you that we are all of one opinion, and that is, that you, Mr. Robin Ogg, have behaved to our friend, Mr. Harry Wakefield here, like a raff and a blackguard."

"Nae doubt, nae doubt," answered Robin with great composure; "and you are a set of very feeling judges, for whose prains or pehaviour I wad not gae a pinch of sneeshing. If Mr. Harry Waakfelt kens where he is wranged, he kens where he may be righted."

"He speaks truth," said Wakefield, who had listened to what passed, divided between the offence which he had taken at Robin's late behaviour, and the revival of his habitual acts of friendship.

He now rose and went towards Robin, who got up from his seat as he approached, and held out his hand.

"That's right, Harry—go it—serve him out!" resounded on all sides—"tip him the nailer—show him the mill."

"Hold your peace, all of you, and be–," said Wakefield; and then addressing his comrade, he took him by the extended hand, with something alike of respect and defiance. "Robin," he said, "thou hast used me ill enough this day; but if you mean, like a frank fellow, to shake hands, and take a tussel for love on the sod, why I'll forgie thee, man, and we shall be better friends than ever."

"And would it not pe petter to be cooed friends without more of the matter?" said Robin; "we will be much petter friendships with our panes hale than broken."

Harry Wakefield dropped the hand of his friend, or rather threw it from him.

"I did not think I had been keeping company for three years with a coward."

"Coward belongs to none of my name," said Robin, whose eyes began to kindle, but keeping the command of his temper. "It was no coward's legs or hands, Harry Waakfelt, that drew you out of the fords of Fried, when you was drifting ower the place rock, and every eel in the river expected his share of you."

"And that is true enough, too," said the Englishman, struck by the appeal.

"Adzooks!" exclaimed the bailiff—"sure Harry Wakefield, the nattiest lad at Whitson Tryste, Wooler Fair, Carlisle Sands, or Stagshaw Bank, is not going to show white feather? Ah, this comes of living so long with kilts and bonnets—men forget the use of their daddies."

"I may teach you, Master Fleecebumpkin, that I have not lost the use of mine," said Wakefield, and then went on. "This will never do, Robin. We must have a turn-up, or we shall be the talk of the country side. I'll be d–d if I hurt thee—I'll put on the gloves gin thou like. Come, stand forward like a man."

"To pe peaten like a dog," said Robin; "is there any reason in that? If you think I have done you wrong, I'll go before your shudge, though I neither know his law nor his language."

A general cry of "No, no—no law, no lawyer! a bellyful and be friends," was echoed by the bystanders.

"But," continued Robin, "if I am to fight, I have no skill to fight like a jackanapes, with hands and nails."

"How would you fight then?" said his antagonist; "though I am thinking it would be hard to bring you to the scratch any how."

"I would fight with proadswords, and sink point on the first plood drawn– like a gentlemans."

A loud shout of laughter followed the proposal, which indeed had rather escaped from poor Robin's swelling heart, than been the dictates of his sober judgment.

"Gentleman, quotha!" was echoed on all sides, with a shout of unextinguishable laughter; "a very pretty gentleman, God wot—Canst get two swords for the gentleman to fight with, Ralph Heskett?"

"No, but I can send to the armoury at Carlisle, and lend them two forks to be making shift with in the meantime."

"Tush, man," said another, "the bonny Scots come into the world with the blue bonnet on their heads, and dirk and pistol at their belt."

"Best send post," said Mr. Fleecebumpkin, "to the squire of Corby Castle to come and stand second to the gentleman."

In the midst of this torrent of general ridicule, the Highlander instinctively griped beneath the folds of his plaid.

"But it's better not," he said in his own language. "A hundred curses on the swine-eaters, who know neither decency nor civility!"

"Make room, the pack of you," he said, advancing to the door.

But his former friend interposed his sturdy bulk, and opposed his leaving the house; and when Robin Oig attempted to make his way by force, he hit him down on the floor, with as much ease as a boy bowls down a nine-pin.

"A ring, a ring!" was now shouted, until the dark rafters, and the hams that hung on them, trembled again, and the very platters on the bink clattered against each other. "Well done, Harry."—"Give it him home, Harry."—"Take care of him now—he sees his own blood!"

Such were the exclamations, while the Highlander, starting from the ground, all his coldness and caution lost in frantic rage, sprung at his antagonist with the fury, the activity, and the vindictive purpose of an incensed tiger-cat. But when could rage encounter science and temper? Robin Oig again went down in the unequal contest; and as the blow was necessarily a severe one, he lay motionless on the floor of the kitchen. The landlady ran to offer some aid, but Mr. Fleecebumpkin would not permit her to approach.

"Let him alone," he said, "he will come to within time, and come up to the scratch again. He has not got half his broth yet."

"He has got all I mean to give him though," said his antagonist, whose heart began to relent towards his old associate; "and I would rather by half give the rest to yourself, Mr. Fleecebumpkin, for you pretend to know a thing or two, and Robin had not art enough even to peel before setting to, but fought with his plaid dangling about him.—Stand up, Robin, my man! all friends now; and let me hear the man that will speak a word against you, or your country, for your sake."

Robin Oig was still under the dominion of his passion, and eager to renew the onset; but being withheld on the one side by the peace-making Dame Heskett, and on the other, aware that Wakefield no longer meant to renew the combat, his fury sunk into gloomy sullenness.

"Come, come, never grudge so much at it, man," said the brave-spirited Englishman, with the placability of his country; "shake hands, and we will be better friends than ever."

"Friends!" exclaimed Robin Oig with strong emphasis—"friends!—Never. Look to yourself, Harry Waakfelt."

"Then the curse of Cromwell on your proud Scots stomach, as the man says in the play, and you may do your worst and be d–; for one man can say nothing more to another after a tussel, than that he is sorry for it."

On these terms the friends parted; Robin Oig drew out, in silence, a piece of money, threw it on the table, and then left the alehouse. But turning at the door, he shook his hand at Wakefield, pointing with his fore-finger upwards, in a manner which might imply either a threat or a caution. He then disappeared in the moonlight.

(To be concluded in our next.)

ARCANA OF SCIENCE

Sheppey.—The isle of Sheppey is quickly giving way to the sea, and if measures are not hereafter taken to remedy this, possibly in a century or two hence its name may be required to be obliterated from the map. Whole acres, with houses upon them, have been carried away in a single storm, while clay shallows, sprinkled with sand and gravel, which stretch a full mile beyond the verge of the cliff, over which the sea now sweeps, demonstrate the original area of the island. From the blue clay of which these cliffs are composed may be culled out specimens of all the fishes, fruits, and trees, which abounded in Britain before the birth of Noah; and the traveller may consequently handle fish which swam, and fruit which grew, in the days of the antediluvians, all now converted into sound stone, by the petrifying qualities of the soil in which they are imbedded. Here are lobsters, crabs, and nautili, presenting almost the same reality as those we now see crawling and floating about; branches of trees, too, in as perfect order as when lopped from their parent stems; and trunks of them, twelve feet in length and two or three diameter, fit, in all appearance, for the operations of the saw, with great varieties of fruits, resembling more those of tropical climates than of cold latitudes like ours, one species having a large kernel, with an adherent stalk, as complete as when newly plucked from the tree that produced it. An interesting collection of these relics of a former world may be seen at a watchmaker's on the cliff, at Margate, including the most remarkable productions of the isle of Sheppey.

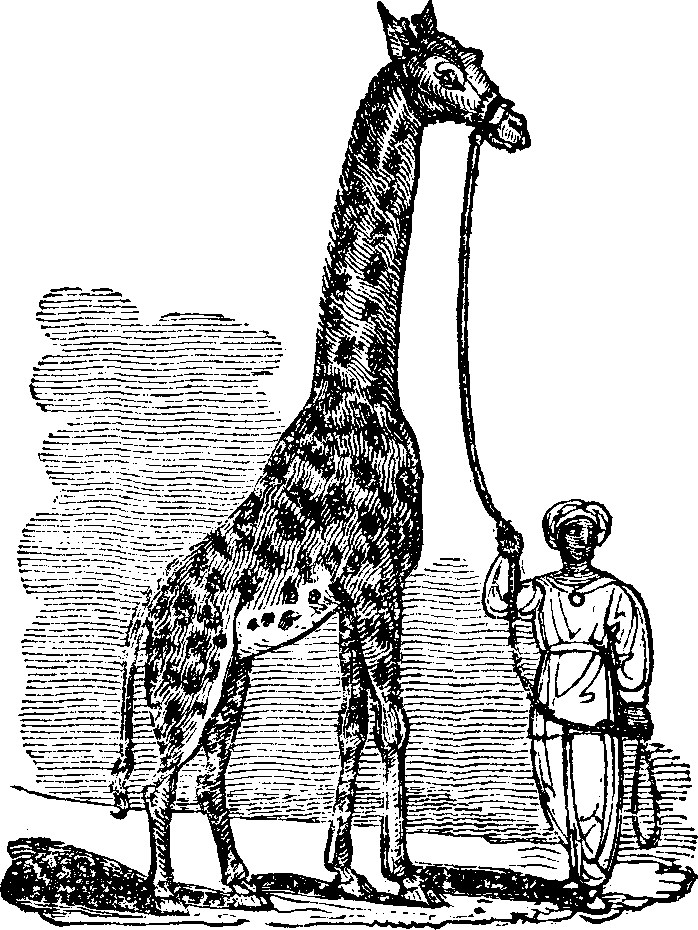

The Camelopard

As a live camelopard has been sent to London and another to Paris, the history and habits of these animals have excited some interest. At a meeting of the Academy of Sciences in Paris, on the 2nd of July last, M. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire observed that naturalists were wrong in supposing that there was only one species of the camelopard. The animal now in Paris differs from the Cape of Good Hope species by several essential anatomical characters, and he proposes to distinguish it by the name of the Giraffe of Sennaar, the country from which it comes. Some natives of Egypt having come to see the one in Paris in the costume of the country, the animal gave evident proofs of joy, and loaded them with caresses. This fact is explained by the circumstance that the Giraffe has an ardent affection for its Arabian keeper, and that it naturally is delighted with the sight of the turban and the costume of its keeper.

Some authors have proved the mildness and docility of the camelopard, while others represent it as incapable of being tamed. This difference is ascribed by M. Saint-Hilaire to difference of education. Four or five years ago a male Giraffe, extremely savage, was brought to Constantinople. The keeper of the present Giraffe had also the charge of this one, and he ascribes its savageness entirely to the manner in which it was treated. At the same time M. Mongez read a memoir on the testimony of ancient authors respecting the Giraffe. Moses is the first author who speaks of it. As Aristotle does not mention it, M. Mongez supposes that it was unknown to the Greeks, and that it did not then exist in Egypt, otherwise Aristotle, who travelled there, must have known about it. In the year 708 of Rome, Julius Caesar brought one to Europe, and the Roman emperors afterwards exhibited them at Rome, either for the games in the circus, or in their triumphs over the African princes. Albertus Magnus, in his Treatise de Animalibus, is the first modern author who speaks of the Giraffe. In 1486, one of the Medici family possessed one at Florence, where it lived for a considerable time.

In its native country the Giraffe browses on the twigs of trees, preferring plants of the Mimosa genus; but it appears that it can without inconvenience subsist on other vegetable food. The one kept at Florence fed on the fruits of the country, and chiefly on apples, which it begged from the inhabitants of the first storeys of the houses. The one now in Paris, from its having been accustomed in early life to the food prepared by the Arabs for their camels, is fed on mixed grains bruised, such as maize, barley, &c., and it is furnished with milk for drink morning and evening. It however willingly accepts fruits and the branches of the acacia which are presented to it. It seizes the leaves with its long rugous and narrow tongue by rolling it about them, and seems annoyed when it is obliged to take any thing from the ground, which it seems to do with difficulty. To accomplish this it stretches first one, then the other of its long fore-legs asunder, and it is not till after repeated attempts that it is able to seize the objects with its lips and tongue.

The pace of the Giraffe is an amble, though when pursued it flies with extreme rapidity, but the small size of its lungs prevents it from supporting a lengthened chase. The Giraffe defends itself against the lion, its principal enemy, with its fore feet, with which it strikes with such force as often to repulse him. The specimen in the museum at Paris is about two years and a half old.

The name Camelo-pardalis (camel-leopard) was given by the Romans to this animal, from a fancied combination of the characters of the camel and leopard; but its ancient denomination was Zurapha, from which the name Giraffe has been adopted.—Brewster's Journal.

SugarAbout 3,700,000 cwt. of sugar are annually imported from the West Indies. An advance in price, therefore, of one penny per pound is a charge on the public of 1,726,600l. a year, being more than one-third of the gross amount of the duty levied at the Custom-house for the revenue.

SilkLord Kingston has upwards of 30,000 mulberry-trees growing upon one estate in Ireland, and has already sent raw silk into the market.

SINGULAR ASSASSINATION IN KINCARDINESHIRE

(For the Mirror.)

The fate of one of the sheriffs of this county, in former times, merits notice, especially as connected with a ruin in the parish of Eccliscraig, formerly a place of great strength, being erected on a perpendicular and peninsulated rock, sixty feet above the sea, at the mouth of a small rivulet. It was built in consequence of a murder committed in the reign of James the First, and the circumstance deserves to be recorded, as it affords a specimen of the barbarity of the times. Melville, sheriff of Kincardineshire, had, by a vigorous exercise of his authority, rendered himself so very obnoxious to the barons of the county, that they had made repeated complaints to the king. On the last of these occasions the king, in a fit of impatience, happened to say to Barclay, of Mathers, "I wish that sheriff were sodden and supped in brue." Barclay instantly withdrew, and reported to his neighbours the king's words, which they resolved literally to fulfil. Accordingly, the conspirators invited the unsuspecting Melville to a hunting party in the forest of Garvock; where, having a fire kindled, and a cauldron of water boiling on it, they rushed to the spot, stripped the sheriff naked, and threw him headlong into the boiling vessel: after which, on pretence of fulfilling the royal mandate, each swallowed a spoonful of the broth. After this cannibal feast, Barclay, to screen himself from the vengeance of the king, built this fortress, which before the invention of gunpowder must have been impregnable. Some of the conspirators were afterwards pardoned. One of the pardons is said to be still in existence; and the reason assigned for granting it is, that the conspirator was within the tenth degree of kin to Macduff, thane of Fife.

CHARLES STUART.

USE OF HORSE-CHESTNUTS

(For the Mirror.)

These nuts are much used in France and in Switzerland, in whitening not only of hemp and flax, but also of silk and wool. They contain a soapy juice, fit for washing of linens and stuffs, for milling of caps and stockings, &c., and for fulling of stuffs and cloths.

Twenty nuts are sufficient for five quarts of water. They must be first peeled, which can be done by children, then rasped or dried, and ground in a malt-mill, or any other common steel mill. The water must be soft, either rain or river water, for hard well water will by no means do. When the nuts are rasped or ground, they must be steeped in the water quite cold, which soon becomes frothy, (as it does with soap,) and then turns white as milk. It must be well stirred at first with a stick, and then, after standing some time to settle, must be strained, or poured off quite clear. Linen washed in this liquor, and afterwards rinsed in clear running water, takes an agreeable light sky-blue colour. It takes spots out of both linen and woollen, and never damages or injures the cloth. Poultry will eat the meal of them, if it is steeped in hot water, and mixed with an equal quantity of pollard. The nuts also are eat by some cows, and without hurting their milk; but they are excellent for horses whose wind is injured.

A.B.

A FETCH

(For the Mirror.)

"I do believe," (as Byron cries,)"There is a haunted spot,And I can point out where it lies,But cannot—where 'tis not.Turn gentle people, lend an ear,Unto my simple tale,It will not draw a single tearNor make the heart bewail,'Tis of a ghost! O ladies fair!Start not with sore affright,It will not harm a single hair,Nor 'make it stand upright."Attend, it was but yesternight,I in my garret sat,I saw—no, nothing yet I saw,But something went pit-pat.So did my heart responsively,Beat like a prison'd bird,That's newly caught—but no replyI made, to what I heard.It nearer came—'Angels,' I cried,'And Ministers of Grace defend.'Yet nothing I as yet descried,My hair stood all on end.My breath was short, I'm sure my eyeWas dim, so was the light,I thought that I that hour should die,With sad and sore affright.And then came o'er me—what came o'er?Some spectre grim I'll bet,O tell me!—why at every pore—A very heavy sweat.Poh, don't delay the wond'rous tale,What follow'd? tell me that,(I feel my heart and limbs too fail)The same thing, pit-a-pat.And then there came before my eyes,I pray thee 'list, O list,'You fill my heart with dread surpriseWhat was it? why a mist.And then around my head there play'dA flame, so wond'rous bright,That made me more than all afraid—My wig had caught the light.And there came wand'ring by at last,The same thing, pit-a-pat,I found as 'cross the room it past,The cat had got a rat.MAY.

TEA

(For the Mirror.)

"The Muses' friend, tea, does our fancy aid,Repress those vapours which the head invade."WALLER.The tea-tree loves to grow in valleys, at the foot of mountains, and upon the banks of rivers, where it enjoys a southern exposure to the sun, though it endures considerable variations of heat and cold, as it flourishes in the northern clime of Peking, as well as about Canton; and it is observed that the degree of cold at Peking is as severe in winter as in some parts of Europe. However, the best tea grows in a mild, temperate climate, the country about Nanking producing better tea than either Peking or Canton, betwixt which places it is situated. The root resembles that of the peach-tree; the leaves are green, longish at the point, and narrow, an inch and half long, and jagged all round. The flower is much like that of the wild rose, but smaller. The fruit is of different forms, sometimes round, sometimes long, sometimes triangular, and of the ordinary size of a bean, containing two or three seeds, of a mouse colour, including each a kernel. These are the seeds by which the plant is propagated, a number, from six to twelve, or fifteen, being promiscuously put into one hole, four or five inches deep, at certain distances from each other. The seeds vegetate without any other care, though the more industrious annually remove the weeds and manure the land. The leaves which succeed are not fit to be plucked before the third year's growth, at which period they are plentiful, and in their prime. In about seven years the shrub rises to a man's height, and as it then bears few leaves, and grows slowly, it is cut down to the stem, which occasions an exuberance of fresh shoots and leaves the succeeding summer. In Japan, the tea-tree is cultivated round the borders of the fields, without regard to soil, but as the Chinese export great quantities of tea, they plant whole fields with it. The tea-trees that yield often the finest leaves, grow on the steep declivities of hills, where it is dangerous and in some cases impracticable to collect them. The Chinese are said to vanquish this difficulty by a singular contrivance. The large monkeys which inhabit these cliffs are irritated, and in revenge they break off the branches and throw them down, so that the leaves are thus obtained. The leaves should be dried as soon as possible after they are gathered. The Chinese are always taking tea, especially at meals; it is the chief treat with which they regale their friends, but they use it without the addition of sugar and milk. Tea was first introduced into Europe by the Dutch East India Company very early in the seventeenth century, and a great quantity of it was brought over from Holland by Lord Arlington and Lord Ossory about the year 1666, at which time it sold for 60s. per pound. Tea exhilarates without intoxication, and its enlivening qualities are equally felt by the sedentary student and the active labourer. Dr. Johnson dearly loved tea, and drank great quantities of this elegant and popular beverage, and so does P.T.W.