полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 13, No. 377, June 27, 1829

Father Guillotin consumed generally more oil than cotton, but I can, nevertheless, affirm, that, in my time, some banquets have been spread at his cabaret, which, subtracting the liquids, could not have cost more at the café Riche, or at Grignon's. I remember six individuals, named Driancourt, Vilattes, Pitroux, and three others, who found means to spend 166 francs there in one night. In fact, each of them had with him his favourite bella. The citizen no doubt pretty well fleeced them, but they did not complain, and that quarter of an hour which Rabelais had so much difficulty in passing, caused them no trouble; they paid like grandees, without forgetting the waiter. I apprehended them whilst they were paying the bill, which they had not even taken the trouble of examining. Thieves are generous when they are caught "i' the vein." They had just committed many considerable robberies, which they are now repenting in the bagnes of France.

It can scarcely be believed that in the centre of civilization, there can exist a den so hideous as the cave of Guillotin; it must be seen, as I have seen it, to be believed. Men and women all smoked as they danced, the pipe passed from mouth to mouth, and the most refined gallantry that could be offered to the nymphs who came to this rendezvous, to display their graces in the postures and attitudes of the indecent Chahut, was, to offer them the pruneau, that is, the quid of tobacco, submitted or not, according to the degree of familiarity, to the test of a previous mastication. The peace-officers and inspectors were characters too greatly distinguished to appear amongst such an assemblage, they kept themselves most scrupulously aloof, to avoid so repugnant a contact; I myself was much disgusted with it, but at the same time was persuaded, that to discover and apprehend malefactors it would not do to wait until they should come and throw themselves into my arms; I therefore determined to seek them out, and that my searches might not be fruitless, I endeavoured to find out their haunts, and then, like a fisherman who has found a preserve, I cast my line out with a certainty of a bite. I did not lose my time in searching for a needle in a bottle of hay, as the saying is; when we lack water, it is useless to go to the source of a dried-up stream and wait for a shower of rain; but to quit all metaphor, and speak plainly—the spy who really means to ferret out the robbers, ought, as much as possible, to dwell amongst them, that he may grasp at every opportunity which presents itself of drawing down upon their heads the sentence of the laws. Upon this principle I acted, and this caused my recruits to say that I made men robbers; I certainly have, in this way, made a vast many, particularly on my first connexion with the police.

CONSUMPTION OF EUROPEAN MANUFACTURES

From the Memoirs of General MillerSecond EditionThe aboriginal inhabitants of Peru are gradually beginning to experience the benefit which has been conferred upon them, by the repeal of ancient oppressive laws. In the districts that produce gold, their exertions will be redoubled, for they now work for themselves. They can obtain this precious metal by merely scratching the earth, and, although the collection of each individual may be small, the aggregate quantity thus obtained will be far from inconsiderable. As the aborigines attain comparative wealth, they will acquire a taste for the minor comforts of life. The consumption of European manufactures will be increased to an incalculable degree, and the effect upon the general commerce of the world will be sensibly perceived. It is for the first and most active manufacturing country in Christendom to take a proper advantage of the opening thus afforded. Already, in those countries, British manufactures employ double the tonnage, and perhaps exceed twenty times the value, of the importations from all other foreign nations put together. The wines and tasteful bagatelles of France, and the flour and household furniture of the United States, will bear no comparison in value to the cottons of Manchester, the linens of Glasgow, the broadcloths of Leeds, or the hardware of Birmingham. All this is proved by the great proportion of precious metals sent to England, as compared with the remittances to other nations. The very watches sent by Messrs. Roskell and Co. of Liverpool, would out-balance the exports of some of the nations which trade to South America.

SOUTH AMERICAN MANNERS

Whether it be the romantic novelty of many places in South America, the salubrity of the climate, the free unrestrained intercourse of the more polished classes, or whether there be some undefinable charm in that state of society which has not passed beyond a certain point of civilization, certain it is that few foreigners have resided for any length of time in Chile, Peru, or in the principal towns of the Pampas, without feeling an ardent desire to revisit them. In this number might be named several European naval officers who have served in the Pacific, and who nave expressed these sentiments, although they move in the very highest circles of England and France. Countries which have not reached the utmost pitch of refinement have their peculiar attractions, as well as the most highly polished nations; but, to the casual resident, the former offers many advantages unattainable in Europe. The virtue of hospitality, exiled by luxury and refinement, exhibits itself in the New World under such noble and endearing forms as would almost tempt the philosopher, as well as the weary traveller, to dread the approach of the factitious civilization that would banish it.

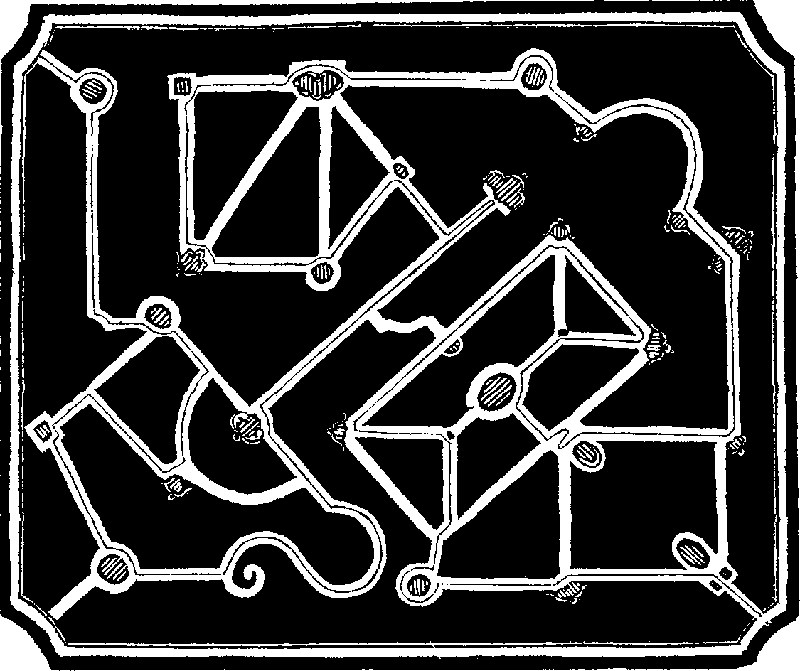

The Labyrinth, at Versailles

This charming labyrinth is attached to Le Petit Trianon at Versailles. The palace and its gardens were formed under the reign of Louis XV., who was there when he was attacked by the contagious disease of which he died. Louis XVI. gave it to his queen, who took great delight in the spot, and had the gardens laid out in the English style. The château, or palace, is situated at one of the extremities of the park of the Grand Trianon, and forms a pavilion, about seventy-two feet square. It consists of a ground floor and two stories, decorated with fluted Corinthian columns and pilasters crowned by a balustrade. The gardens are delightful: here is a temple of love; there an artificial rock from which water rushes into a lake; there a picturesque wooden bridge, a rural hamlet, grottoes, cottages embowered in groves of trees, diversified with statues and seats—and above all, the fascinating MAZE, the plan of which is represented in the Engraving.

Versailles, its magnificent palace and gardens, are altogether fraught with melancholy associations. When we last saw them, the grounds and buildings presented a sorry picture of neglect and decay. The mimic lakes and ponds were green and slimy, the grottoes and shell-work crumbling away, the fountains still, and the cascades dry. But the latter are exhibited on certain days during the summer, when the gardens are thronged with gay Parisians. The most interesting object however, is, the orange-tree planted by Francis I. in 1421, which is in full health and bearing: alas! we halted beside it, and thought of the wonderful revolutions and uprootings that France had suffered since this tree was planted.

In Le Petit Trianon and its grounds the interesting Queen Marie Antoinette passed many happy hours of seclusion; and would that her retreat had been confined to the maze of Nature, rather than she had been engaged in the political intrigues which exposed her to the fury of a revolutionary mob. In the palace we were shown the chamber of Marie Antoinette, where the ruffians stabbed through the covering of the bed, the queen having previously escaped from this room to the king's chamber; and, as if to keep up the folly of the splendid ruin, a gilder was renovating the room of the ill-starred queen.

RECENT BALLOON ASCENT

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

I trust you will pardon my feeble attempt last week, and I wish you had been in the car with us, to have witnessed the magnificent scene, and the difficulty of describing it. At our ascent we rose, in a few seconds, 600 feet; and instantly a flood of light and beautiful scenery burst forth. Picture to yourself the Thames with its shipping; Greenwich with its stately Hospital and Park; Blackwall, Blackheath, Peckham, Camberwell, Dulwich, Norwood, St. Paul's, the Tower of London, &c. and the surrounding country, all brought immediately into your view, all apparently receding, and lit up into magnificence by the beams of a brilliant evening sun, (twenty-seven minutes past seven,) and then say who can portray or describe the scene, I say I cannot.

P.T.WTHE NATURALIST

BEES

The faculty, or instinct of bees is sometimes at fault, for we often hear of their adopting the strangest and most unsuitable tenements for the construction of cells. A hussar's cap, so suspended from a moderate sized branch of a tree, as to be agitated by slight winds, was found filled with bees and comb. An old coat, that had been thrown over the decayed trunk of a tree and forgotten, was filled with comb and bees. Any thing, in short, either near the habitations of man, or in the forests, will serve the bees for a shelter to their combs.

The average number of a hive, or swarm, is from fifteen to twenty thousand bees. Nineteen thousand four hundred and ninety-nine are neuters or working bees, five hundred are drones, and the remaining one is the queen or mother! Every living thing, from man down to an ephemeral insect, pursues the bee to its destruction for the sake of the honey that is deposited in its cell, or secreted in its honey-bag. To obtain that which the bee is carrying to its hive, numerous birds and insects are on the watch, and an incredible number of bees fall victims, in consequence, to their enemies. Independently of this, there are the changes in the weather, such as high winds, sudden showers, hot sunshine; and then there is the liability to fall into rivers, besides a hundred other dangers to which bees are exposed.

When a queen bee ceases to animate the hive, the bees are conscious of her loss; after searching for her through the hive, for a day or more, they examine the royal cells, which are of a peculiar construction and reversed in position, hanging vertically, with the mouth underneath. If no eggs or larvae are to be found in these cells, they then enlarge several of those cells, which are appropriated to the eggs of neuters, and in which queen eggs have been deposited. They soon attach a royal cell to the enlarged surface, and the queen bee, enabled now to grow, protrudes itself by degrees into the royal cell, and comes out perfectly formed, to the great pleasure of the bees.

The bee seeks only its own gratification in procuring honey and in regulating its household, and as, according to the old proverb, what is one man's meat is another's poison, it sometimes carries honey to its cell, which is prejudicial to us. Dr. Barton in the fifth volume, of the "American Philosophical Transactions," speaks of several plants that yield a poisonous syrup, of which the bees partake without injury, but which has been fatal to man. He has enumerated some of these plants, which ought to be destroyed wherever they are seen, namely, dwarf-laurel, great laurel, kalmia latifolia, broad-leaved moorwort, Pennsylvania mountain-laurel, wild honeysuckle (the bees, cannot get much of this,) and the stramonium or Jamestown-weed.

A young bee can be readily distinguished from an old one, by the greyish coloured down that covers it, and which it loses by the wear and tear of hard labour; and if the bee be not destroyed before the season is over, this down entirely disappears, and the groundwork of the insect is seen, white or black. On a close examination, very few of these black or aged bees, will be seen at the opening of the spring, as, not having the stamina of those that are younger, they perish from inability to encounter the vicissitudes of winter.—American Farmer's Manual.

THE ELM

(To the Editor of the Mirror.)

I shall be obliged to any of your correspondents who can inform me from whence came the term witch-elm, a name given to a species of elm tree, to distinguish it from the common elm. Some people have conjectured that it was a corruption of white elm, and so called from the silvery whiteness of its leaves when the sun shines upon them; but this is hardly probable, as Sir F. Bacon in his "Silva Silvarum, or Natural History, in Ten Centuries," speaks of it under the name of weech-elm.

H.B.ACROP OF BIRDS

Besides the stomach, most birds have a membranous sac, capable of considerable distension; it is usually called a crop, (by the scientific Ingluvies,) into which the food first descends after being swallowed. This bag is very conspicuous in the granivorous tribes immediately after eating. Its chief use seems to be to soften the food before it is admitted into the gizzard. In young fowls it becomes sometimes preternaturally distended, while the bird pines for want of nourishment. This is produced by something in the crop, such as straw, or other obstructing matter, which prevents the descent of the food into the gizzard. In such a case, a longitudinal incision may be made in the crop, its contents removed, and, the incision being sewed up, the fowl will, in general, do well.

Another curious fact relative to this subject was stated by Mr. Brookes, when lecturing on birds at the Zoological Society, May 1827. He had an eagle, which was at liberty in his garden; happening to lay two dead rats, which had been poisoned, under a pewter basin, to which the eagle could have access, but who nevertheless did not see him place the rats under it, he was surprised to see, some time afterwards, the crop of the bird considerably distended; and finding the rats abstracted from beneath the basin, he concluded that the eagle had devoured them. Fearing the consequences, he lost no time in opening the crop, took out the rats, and sewed up the incision; the eagle did well and is now alive. A proof this of the acuteness of smell in the eagle, and also of the facility and safety with which, even in grown birds, the operation of opening the crop may be performed.—Jennings's Ornithologia.

HATCHING

The following singular fact was first brought into public notice by Mr. Yarrel; and will be found in his papers in the second volume of the Zoological Journal. The fact alluded to is, that there is attached to the upper mandible of all young birds about to be hatched a horny appendage, by which they are enabled more effectually to make perforations in the shell, and contribute to their own liberation. This sharp prominence, to use the words of Mr. Yarrel, becomes opposed to the shell at various points, in a line extending throughout its whole circumference, about one third below the larger end of the egg; and a series of perforations more or less numerous are thus effected by the increasing strength of the chick, weakening the shell in a direction opposed to the muscular power of the bird; it is thus ultimately enabled, by its own efforts, to break the walls of its prison. In the common fowl, this horny appendage falls off in a day or two after the chick is hatched; in the pigeon it sometimes remains on the beak ten or twelve days; this arises, doubtless, from the young pigeons being fed by the parent bird for some time after their being hatched; and thus there is no occasion for the young using the beak for picking up its food.—Ibid.

MAN.—A FRAGMENT

Man is a monster,The fool of passion and the slave of sin.No laws can curb him when the will consentsTo an unlawful deed.CYMBELINE.SPIRIT OF THE PUBLIC JOURNALS

THE CHOSEN ONE

"Here's a long line of beauties—see!Ay, and as varied as they're many—Say, can I guess the one would beYour choice among them all—if any?""I doubt it,—for I hold as dustCharms many praise beyond all measure—While gems they treat as lightly, mustCombine to form my chosen treasure.""Will this do?"—"No;—that hair of gold,That brow of snow, that eye of splendour,Cannot redeem the mien so cold,The air so stiff, so quite un-tender.""This then?"—"Far worse! Can lips like theseThus smile as though they asked the kiss?—Thinks she that e'en such eyes can please,Beaming—there is no word—like this?""Look on that singer at the harp,Of her you cannot speak thus—ah, no!"—"Her! why she's formed of flat and sharp—I doubt not she's a fine soprano!""The next?"—"What, she who lowers her eyesFrom sheer mock-modesty—so pert,So doubtful-mannered?—I despiseHer, and all like her—she's a Flirt!"And this is why my spleen's aboveThe power of words;—'tis that they canMake the vile semblance be to LoveJust what the Monkey is to Man!"But yonder I, methinks, can traceOne very different from these—Her features speak—her form is GraceCompleted by the touch of Ease!"That opening lip, that fine frank eyeBreathe Nature's own true gaiety—So sweet, so rare when thus, that IGaze on't with joy, nay ecstacy!"For when 'tis thus, you'll also seeThat eye still richer gifts express—And on that lip there oft will beA sighing smile of tenderness!"Yes! here a matchless spirit dwellsE'en for that lovely dwelling fit!—I gaze on her—my bosom swellsWith feelings, thoughts,–oh! exquisite!"That such a being, noble, tender,So fair, so delicate, so dear,Would let one love her, and befriend her!——Ah, yes, my Chosen One is here!"London Magazine.

TRAVELLING ON THE CONTINENT

The man whom we have known to be surrounded by respect and attachment at home, whose life is honourable and useful within his proper sphere, we have seen with his family drudging along continental roads, painfully disputing with postilions in bad French, insulted by the menials of inns, fretting his time and temper with the miserable creatures who inflict their tedious ignorance under the name of guides, and only happy in reaching any term to the journey which fashion or family entreaty have forced upon him. We are willing, however, to regard such instances as casual, and proving only that travelling, like other pleasures, has its alloys; but stationary residence abroad brings with it other and more serious evils. To the animation of a changing scene of travel, succeeds the tedious idleness of a foreign town, with scanty resources of society, and yet scantier of honourable or useful occupation. Here also we do but describe what we have too frequently seen—the English gentleman, who at home would have been improving his estates, and aiding the public institutions of his country, abandoned to utter insignificance; his mind and resources running waste for want of employment, or, perchance, turned to objects to which even idleness might reasonably be preferred. We have seen such a man loitering along his idle day in streets, promenades, or coffee-houses; or sometimes squandering time and money at the gambling-table, a victim because an idler. The objects of nature and art, which originally interested him, cease altogether to do so.

We admit many exceptions to this picture; but we, nevertheless, draw it as one which will be familiar to all, who have been observers on the continent. One circumstance must further be added to the outline; we mean, the detachment from religious habits, which generally and naturally attends such residence abroad. The means of public worship exist to our countrymen but in few places; and there under circumstances the least propitious to such duties. Days speedily become all alike; or if Sunday be distinguished at all, it is but as the day of the favourite opera, or most splendid ballet of the week. We are not puritanically severe in our notions, and we intend no reproach to the religious or moral habits of other nations. We simply assert, that English families removed from out of the sphere of those proper duties, common to every people, and from all opportunities of public worship or religious example, incur a risk which is very serious in kind, especially to those still young and unformed in character.

Quarterly Review.

RETROSPECTIVE GLEANINGS

ANCIENT FARRIERY

(For the Mirror.)

The following curious verses are copied from an engraving which the Farriers' Company have lately had taken from an old painting of their pedigree, on vellum, at the George and Vulture Tavern.

If suche may boast as by a subtile arte,Canne without labour make excessive gayne,And under name of Misterie imparte,Unto the worlde the Crafie's but of their brayne.How muche more doe their praise become men's themesThat bothe by art and labour gett their meanes.And of all artes that worthe or praise doeth merite,To none the Marshall Farrier's will submitt,That bothe by Physicks, arte, force, hands, and spirittThe Kinge and subject in peace and warre doe fitt,Many of Tuball boast first Smythe that ever wrought,But Farriers more do, doe than Tuball ever taught.Three things there are that Marshalry doe proveTo be a Misterie exceeding farre,Those wilie Crafte's that many men doe love.Is unfitt for peace and more unaptt for warre,For Honor, Anncestrie, and for Utilitie,Farriers may boast their artes habilitie,For Honor, view, this anncient Pedigree2Of Noble Howses, that did beare the nameOf Farriers, and were Earles; as you may see,That used the arte and did supporte the same,And to perpetuall honour of the Crafte,Castells they buylt and to succession left.For anncestrie of tyme oh! who canne tellThe first beginning of so old a trade,For Horses were before the Deluge fell,And cures, and shoes, before that tyme were made,We need not presse tyme farther then it beares,A Company have Farriers beene 300 Yeres!!And in this Cittie London have remaynedCalled by the name of Marshall Farriers,Which title of Kinge Edward the Third was gaynde,For service done unto him in his warres,A Maister and two Wardens in skill expert,The trade to rule and give men their desert.And for utilitie that cannot be denied,That many are the Proffitts that ariseTo all men by the Farriers arte beside.To them they are tied, by their necessities,From the Kinge's steede unto the ploweman's cart,All stande in neede of Farriers skillfull arte.In peace at hande the Farriers must be hadde,For lanncing, healinge, bleedinge, and for shooeinge,In Warres abroade of hym they wille be gladdTo cure the wounded Horsse, still he is douinge,In peace or warre abroade, or ellse at home,To Kinge and Countrie that some good may come.Loe! thus you heare the Farriers endelesss praise,God grant it last as many yeres as it hath lasted Daies.Anno Dni 1612.

G.WCURIOUS SCRAPS

We read of a beautiful table, "wherein Saturn was of copper, Jupiter of gold, Mars of iron, and the Sun of silver, the eyes were charmed, and the mind instructed by beholding the circles. The Zodiac and all its signs formed with wonderful art, of metals and precious stones."

Was not this an imperfect orrery?

In 1283, say the annals of Dunstable, "We sold our slave by birth, William Pike, with all his family, and received one mark from the buyer." Men must have been cheaper than horses.

In 1340, gunpowder and guns were first invented by Swartz, a monk of Cologne. In 1346, Edward III. had four pieces of cannon, which contributed to gain him the battle of Cressy. Bombs and mortars were invented about this time.

In 1386, the magnificent castle of Windsor was built by Edward III. and his method of conducting the work may serve as a specimen of the condition of the people in that age. Instead of engaging workmen by contracts or wages, he assessed every county in England to send him a certain number of masons, tilers, and carpenters, as if he had been levying an army.