полная версия

полная версияThe Half-Back: A Story of School, Football, and Golf

Play had begun this morning at nine o'clock, and by noon only Somers, Whipple, and West had been left in the match. Blair had encountered defeat most unexpectedly at the hands of Greene, a junior, of whose prowess but little had been known by the handicapper; for, although Blair had done the round in three strokes less than his adversary's gross score, the latter's allowance of six strokes had placed him an easy winner. But Blair had been avenged later by West, who had defeated the youngster by three strokes in the net. In the afternoon Somers and Whipple had met, and, as West had predicted, the latter won by two strokes.

And now West and Whipple, both excellent players, and sworn enemies of the links, were fighting it out, and on this round depended the possession of the title of champion and the ownership for one year of the handicap cup, a modest but highly prized pewter tankard. Medal Play rules governed to-day, and the scoring was by strokes.

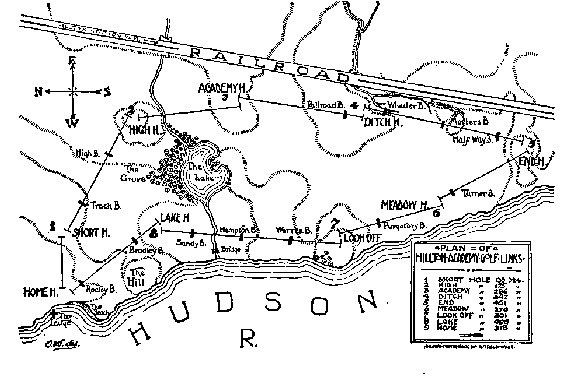

"Plan of Hilton Academy Golf Links."

Whipple reached the first green in one stroke, but used two more to hole-out. West took two short drives to reach a lie, from which he dropped his ball into the hole in one try. And the honors were even. The next hole was forty yards longer, and was played either in two short drives or one long drive and an approach shot. It contained two hazards, Track Bunker and High Bunker, the latter alone being formidable. Whipple led off with a long shot that went soaring up against the blue and then settled down as gently as a bird just a few yards in front of High Bunker. He had reversed his play of the last hole, and was now relying on his approach shot for position. West played a rather short drive off an iron which left his ball midway between the two bunkers. Whipple's next stroke took him neatly out of danger and on to the putting green, but West had fared not so well.

There was a great deal of noise from the younger boys who were looking on, much discussion of the methods of play, and much loud boasting of what some one else would have done under existing circumstances. West glanced up once and glared at one offending junior, and an admonitory "Hush!" was heard. But he was plainly disturbed, and when the little white sphere made its flight it went sadly aglee and dropped to earth far to the right of the green, and where rough and cuppy ground made exact putting well-nigh impossible. Professor Beck promptly laid down a command of absolute silence during shots, and some of the smaller youths left the course in favor of another portion of the campus, where a boy's right to make all the noise he likes could not be disputed. But the harm was done, and when play for the third hole began the score was: Whipple 7, West 8.

Even to one of such intense ignorance of the science of golf as Joel March, there was a perceptible difference in the style of the two competitors. Outfield West was a great stickler for form, and imitated the full St. Andrews swing to the best of his ability. In addressing the ball he stood as squarely to it as was possible, without the use of a measuring tape, and drove off the right leg, as the expression is. Despite an almost exaggerated adherence to nicety of style, West's play had an ease and grace much envied by other golf disciples in the school, and his shots were nearly always successful.

Whipple's manner of driving was very different from his opponent's. His swing was short and often stopped too soon. His stance was rather awkward, after West's, and even his hold on the club was not according to established precedent. Yet, notwithstanding all this, it must be acknowledged that Whipple's drives had a way of carrying straight and far and landing well.

Joel followed the play with much interest if small appreciation of its intricacies, and carried West's bag, and hoped all the time that that youth would win, knowing how greatly he had set his heart upon so doing.

There is no bunker between second and third holes, but the brook which supplies the lake runs across the course and is about six yards wide from bank to bank. But it has no terrors for a long drive, and both the players went safely over and won Academy Hole in three strokes. West still held the odd. Two long strokes carried Whipple a scant distance from Railroad Bunker, which fronts Ditch Hole, a dangerous lie, since Railroad Bunker is high and the putting green is on an elevation, almost meriting the title of hill, directly back of it. But if Whipple erred in judgment or skill, West found himself in even a sorrier plight when two more strokes had been laid to his score. His first drive with a brassie had fallen rather short, and for the second he had chosen an iron. The ball sailed off on a long flight that brought words of delight from the spectators, but which caused Joel to look glum and West to grind the turf under his heel in anger. For, like a thing possessed, that ball fell straight into the very middle of the bunker, and when it was found lay up to its middle in gravel.

West groaned as he lifted the ball, replaced it loosely in its cup, and carefully selected a club. Whipple meanwhile cleared the bunker in the best of style, and landed on the green in a good position to hole out in two shots. "Great Gobble!" muttered West as he swung his club, and fixed his eye on a point an inch and a half back of the imbedded ball, "if I don't get this out of here on this shot, I'm a gone goose!" March grinned sympathetically but anxiously, and the onlookers held their breath. Then back went the club–there was a scattering of sand and gravel, and the ball dropped dead on the green, four yards from the hole.

"Excellent!" shouted Professor Beck, and Joel jumped in the air from sheer delight. "Good for you, Out!" yelled Dave Somers; and the rest of the watchers echoed the sentiment in various ways, even those who desired to see Whipple triumphant yielding their meed of praise for the performance. And, "I guess, Out," said Whipple ruefully, "you might as well take the cup." But Outfield West only smiled silently in response, and followed his ball with businesslike attention to the game.

Whipple was weak on putting, and his first stroke with an iron failed to carry his ball to the hole. West, on the contrary, was a sure player on the green, and now with his ball but four yards from the hole he had just the opportunity he desired to better his score. The green was level and clean, and West selected a small iron putter, and addressed the ball with all the attention to form that the oldest St. Andrews veteran might desire. Playing on the principle that it is better to go too far than not far enough, since the hole is larger than the ball, West gave a long stroke, and the gutta-percha disappeared from view. Whipple holed out on his next try, adopting a wooden putter this time, and the score stood fifteen strokes each.

The honor was West's, and he led off for End Hole with a beautiful brassie drive that cleared the first two bunkers with room to spare. Whipple, for the first time in the round, drove poorly, toeing his ball badly, and dropping it almost off of the course and just short of the second bunker. West's second drive was a loft over Halfway Bunker that fell fairly on the green and rolled within ten feet of the hole. From there, on the next shot, he holed out very neatly in eighteen. Whipple meanwhile had redeemed himself with a high lofting stroke that carried past the threatening dangers of Masters Bunker and back on to the course within a few yards of West's lie. But again skill on the putting green was wanting, and he required two strokes to make the hole. Once more the honor was West's, and that youth turned toward home with a short and high stroke. The subsequent hole left the score "the like" at 22, and the seventh gave Whipple, 25, West 26.

"But here's where Mr. West takes the lead," confided that young gentleman to Joel as they walked to the teeing ground. "From here to Lake Hole is four hundred and ninety-six yards, and I'm going to do it in three shots on to the green. You watch!"

Four hundred and ninety-odd yards is nothing out of the ordinary for an older player, but to a lad of seventeen it is a creditable distance to do in three drives. Yet that is what West did it in; and strange to relate, and greatly to that young gentleman's surprise, Whipple duplicated the performance, and amid the excited whispers of the onlookers the two youths holed out on their next strokes; and the score still gave the odd to West–29 to 30.

"I didn't think he could do it," whispered West to Joel, "and that makes it look bad for your uncle Out. But never mind, my lad, there's still Rocky Bunker ahead of us, and–" West did not complete his remark, but his face took on a very determined look as he teed his ball. The last hole was in sight, and victory hovered overhead.

Now, the distance from Lake Hole to the Home Hole is but a few yards over three hundred, and it can be accomplished comfortably in two long brassie drives. Midway lies The Hill, a small elevation rising from about the middle of the course to the river bluff, and there falling off sheer to the beach below. It is perhaps thirty yards across, and if the ball reaches it safely it forms an excellent place from which to make the second drive. So both boys tried for The Hill. Whipple landed at the foot of it, while West came plump upon the side some five yards from the summit, and his next drive took him cleanly over Rocky Bunker and to the right of the Home Green. But Whipple summoned discretion to his aid, and instead of trying to make the green on the next drive, played short, and landed far to the right of the Bunker. This necessitated a short approach, and by the time he had gained the green and was "made" within holing distance of the flag, the score was once more even, and the end was in sight.

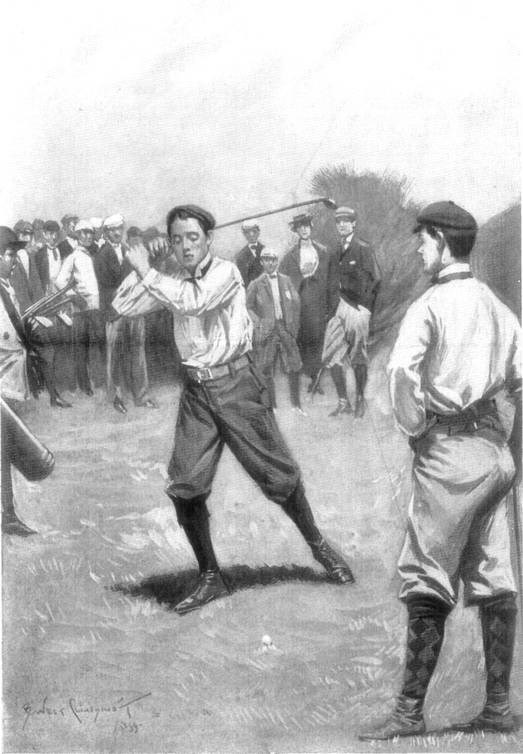

"His next drive took him cleanly over Rocky Bunker.

And now the watchers moved about restlessly, and Joel found his heart in his throat. But West gripped his wooden putter firmly and studied the situation. It was quite possible for a skillful player to hole out on the next stroke from Whipple's lie. West, on the contrary, was too far distant to possess more than one chance in ten of winning the hole in one play. Whether to take that one chance or to use his next play in bettering his lie was the question. Whipple, West knew, was weak on putting, but it is ever risky to rely on your opponent's weakness. While West pondered, Whipple studied the lay of the green with eyes that strove to show no triumph, and the little throng kept silence save for an occasional nervous whisper.

Then West leaned down and cleared a pebble from before his ball. It was the veriest atom of a pebble that ever showed on a putting green, but West was willing to take no chances beyond those that already confronted him. His mind was made up. Gripping his iron putter firmly rather low on the shaft and bending far over, West slowly, cautiously swung the club above the gutty, glancing once and only once as he did so at the distant goal. Then there was a pause. Whipple no longer studied his own play; his eyes were on that other sphere that nestled there so innocently against the grass. Joel leaned breathlessly forward. Professor Beck muttered under his breath, and then cried "S–sh!" to himself in an angry whisper. And then West's club swung back gently, easily, paused an instant–and–

Forward sped the ball–on and on–slower–slower–but straight as an arrow–and then–Presto! it was gone from sight!

A moment of silence followed ere the applause broke out, and in that moment Professor Beck announced:

"The odd to Whipple. Thirty-two to thirty-three."

Then the group became silent again. Whipple addressed his ball. It was yet possible to tie the score. His face was pale, and for the first time during the tournament he felt nervous. A better player could scarce have missed the hole from Whipple's lie, but for once that youth's nerve forsook him and he hit too short; the ball stopped a foot from the hole. The game was decided. Professor Beck again announced the score:

"The two more to Whipple. Thirty-two to thirty-four."

Again Whipple addressed his ball, and this time, but too late to win the victory, the tiny sphere dropped neatly into the hole, and the throng broke silence. And as West and Whipple, victor and vanquished, shook hands over the Home Hole, Professor Beck announced:

"Thirty-two to thirty-five. West wins the Cup!"

CHAPTER IX.

AN EVENING CALL

The last week of October brought chilling winds and flying clouds. Life at Hillton Academy had gone on serenely since West's victory on the links. The little pewter tankard reposed proudly upon his mantel beside a bottle of chow-chow, and bore his name as the third winner of the trophy. But West had laid aside his clubs, save for an occasional hour at noon, and, abiding by his promise to Joel, he had taken up his books again with much resolution, if little ardor. Hillton had met and defeated two more football teams, and the first eleven was growing gradually stronger. Remsen was seen to smile now quite frequently during practice, and there was a general air of prosperity about the gridiron.

The first had gone to its training table at "Mother" Burke's, in the village, and the second ate its meals in the center of the school dining hall with an illy concealed sense of self-importance. And the grinds sneered at its appetites, and the obscure juniors admired reverently from afar. Joel had attended both recitations and practice with exemplary and impartial regularity, and as a result his class standing was growing better and better on one hand, and on the other his muscles were becoming stronger, his flesh firmer, and his brain clearer.

The friendship between him and Outfield West had ripened steadily, until now they were scarcely separable. And that they might be more together West had lately made a proposition.

"That fellow Sproule is a regular cad, Joel, and I tell you what we'll do. After Christmas you move over to Hampton and room with me. You have to make an application before recess, you know. What do you say?"

"I should like to first rate, but I can't pay the rent there," Joel had objected.

"Then pay the same as you're paying for your den in Masters," replied West. "You see, Joel, I have to pay the rent for Number 2 Hampton anyhow, and it won't make any difference whether I have another fellow in with me or not. Only, if you pay as much of my rent as you're paying now, why, that will make it so much cheaper for me. Don't you see?"

"Yes, but if I use half the room I ought to pay half, the rent." And to this Joel stood firm until West's constant entreaties led to a compromise. West was to put the matter before his father, and Joel before his. If their parents sanctioned it, Joel was to apply for the change of abode. As yet the matter was still in abeyance.

Richard Sproule, as West had suggested rather more forcibly than politely, was becoming more and more objectionable, and Joel was not a bit grieved at the prospect of leaving him. Of late, intercourse between the roommates had become reduced to rare monosyllables. This was the outcome of a refusal on Joel's part to give a portion of his precious study time to helping Sproule with his lessons. Once or twice Joel had consented to assist his roommate, and had done so to the detriment of his own affairs; but the result to both had proved so unsatisfactory that Joel had stoutly refused the next request. Thereupon Sproule had considered himself deeply aggrieved, and usually spent the time when Joel was present in sulking.

Bartlett Cloud, since his encounter with Joel on the field the afternoon that he was put off the team, had had nothing to say to him, though his looks when they met were always dark and threatening. But in a school as large as Hillton there is plenty of room to avoid an objectionable acquaintance, so long as you are not under the same roof with him, and consequently Cloud and Joel seldom met. The latter constantly regretted having made an enemy of the other, but beyond this regret his consideration of Cloud seldom went.

So far Joel had not found an opportunity to accept the invitation that Remsen had extended to him, though that invitation had since been once or twice repeated. But to-night West and he had made arrangement to visit Remsen at his room, and had obtained permission from Professor Wheeler to do so. The two boys met at the gymnasium after supper was over and took their way toward the village. West had armed himself with a formidable stick, in the hope, loudly expressed at intervals, that they would be set upon by tramps. But Remsen's lodgings were reached without adventure, and the lads were straightway admitted to a cosey study, wherein, before an open fire, sat Remsen and a guest. After a cordial welcome from Remsen the guest was introduced as Albert Digbee.

"Yes, we know each other," said West, as he shook hands. "We both room in Hampton, but Digbee's a grind, you know, and doesn't care to waste his time on us idlers." Digbee smiled.

"It isn't inclination, West; I don't have the time, and so don't attempt to keep up with you fellows." He shook Joel's hand. "I'm glad to meet you. I've heard of you before."

Then the quartet drew chairs up to the blaze, and, as Remsen talked, Joel examined his new acquaintance.

Digbee was a year older than West and Joel. He was in the senior class, and was spoken of as one of the smartest boys in the school. Although a Hampton House resident, he seldom was seen with the others save at the table, and was usually referred to among themselves as "Dig," both because that suggested his Christian name and because, as they said, he was forever digging at his books. In appearance Albert Digbee was a tall, slender, but scarcely frail youth, with a cleanly cut face that looked, in the firelight, far too pale. His eyes were strikingly bright, and though his smiles were infrequent, his habitual expression was one of eager and kindly interest. Joel had often come across him in class, and had long wanted to know him.

"You see, boys," Remsen was saying, "Digbee here is of the opinion that athletics in general and football in particular are harmful to schools and colleges as tending to draw the attention of pupils from their studies, and I maintain the opposite. Now, what's your opinion, West? Digbee and I have gone over it so often that we would like to hear some one else on the subject."

"Oh, I don't know," replied West. "If fellows would give up football and go in for golf, there wouldn't be any talk about athletics being hurtful. Golf's a game that a chap can play and get through with and have some time for study. You don't have to train a month to play for an hour; it's a sport that hasn't become a business."

"I can testify," said Joel gravely, "that Out is a case in point. He plays golf, and has time left to study–how to play more golf."

"Well, anyhow, you know I do study some lately, Joel," laughed West. Joel nodded with serious mien.

"I think you've made a very excellent point in favor of golf, West," said Digbee. "It hasn't been made a business, at least in this school. But won't it eventually become quite as much of a pursuit as football now is?"

"Oh, it may become as popular, but, don't you see, it will never become as–er–exacting on the fellows that play it. You can play golf without having to go into training for it."

"Nevertheless, West," replied the head coach, "if a fellow can play golf without being in training, doesn't it stand to reason that the same fellow can play a better game if he is in training? That is, won't he play a better game if he is in better trim?"

"Yes, I guess so, but he will play a first-class game if he doesn't train."

"But not as good a game as he will if he does train?"

"I suppose not," admitted West.

"Well, now, a fellow can play a very good game of football if he isn't in training," continued Remsen, "but that same fellow, if he goes to bed and gets up at regular hours, and eats decent food at decent times, and takes care of himself in such a way as to improve his mental, moral, and physical person, will play a still better game and derive more benefit from it. When golf gets a firmer hold on this side of the Atlantic, schools and colleges will have their golf teams of, say, from two to a dozen players. Of course, the team will not play as a team, but the members of it will play singly or in couples against representatives of other schools. And when that happens it is sure to follow that the players will go into almost as strict training as the football men do now."

"Well, that sounds funny," exclaimed West.

"Digbee thinks one of the most objectionable features of football is the fact that the players go into it so thoroughly–that they train for it, and study it, and spend a good deal of valuable time thinking about it. But to me that is one of its most admirable features. When a boy or a man goes in for athletics, whether football or rowing or hockey, he desires, if he is a real flesh-and-blood being, to excel in it. To do that it is necessary that he put himself in the condition that will allow of his doing his very best. And to that end he trains. He gives up pastry, and takes to cereals; he abandons his cigarettes and takes to fresh air; he gives up late hours at night, and substitutes early hours in the morning. And he is better for doing so. He feels better, looks better, works better, plays better."

"But," responded Digbee, "can a boy who has come to school to study, and who has to study to make his schooling pay for itself, can such a boy afford the time that all that training and practicing requires?"

"Usually, yes," answered Remsen. "Of course, there are boys, and men too, for that matter, who are incapable of occupying their minds with two distinct interests. That kind should leave athletics alone. And there are others who are naturally–I guess I mean-unnaturally–stupid, and who, should they attempt to sandwich football or baseball into their school life, would simply make a mess of both study and recreation. But they need not enter into the question of the harm or benefit of athletics, since at every well-conducted school or college those boys are not allowed to take up with athletics. Yes, generally speaking, the boy who comes to school to study can afford to play football, train for football, and think football, because instead of interfering with his studies it really helps him with them. It makes him healthy, strong, wide-awake, self-reliant, and clearheaded. Some time I shall be glad to show you a whole stack of careful statistics which prove that football men, at least, rather than being backward with studies, are nearly always above the average in class standing. March, you're a hard-worked football enthusiast, and I understand that you're keeping well up with your lessons. Do you have trouble to attend to both? Do you have to skimp your studies? I know you give full attention to the pigskin."

"I'm hard put some days to find time for everything," answered Joel, "but I always manage to make it somehow, and I have all the sleep I want or need. Perhaps if I gave up football I might get higher marks in recitations, but I'd not feel so well, and it's possible that I'd only get lower marks. I agree with you, Mr. Remsen, that athletics, or at least football, is far more likely to benefit a chap than to hurt him, because a fellow can't study well unless he is in good health and spirits."

"Are you convinced, Digbee?" asked Remsen. Digbee shook his head smilingly.

"I don't believe I am, quite. But you know more about such things than I do. In fact, it's cheeky for me to argue about them. Why, I've never played anything but tennis, and never did even that well."

"You know the ground you argue from, and because I have overwhelmed you with talk it does not necessarily follow that I am right," responded his host courteously. "But enough of such dull themes. There's West most asleep.–March, have you heard from your mother lately?"

"Yes, I received a letter from her yesterday morning. She writes that she's glad the relationship is settled finally; says she's certain that any kin of the Maine Remsens is a person of good, strong moral character." When the laugh had subsided, Remsen turned to West.