полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 488, May 7, 1831

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 17, No. 488, May 7, 1831

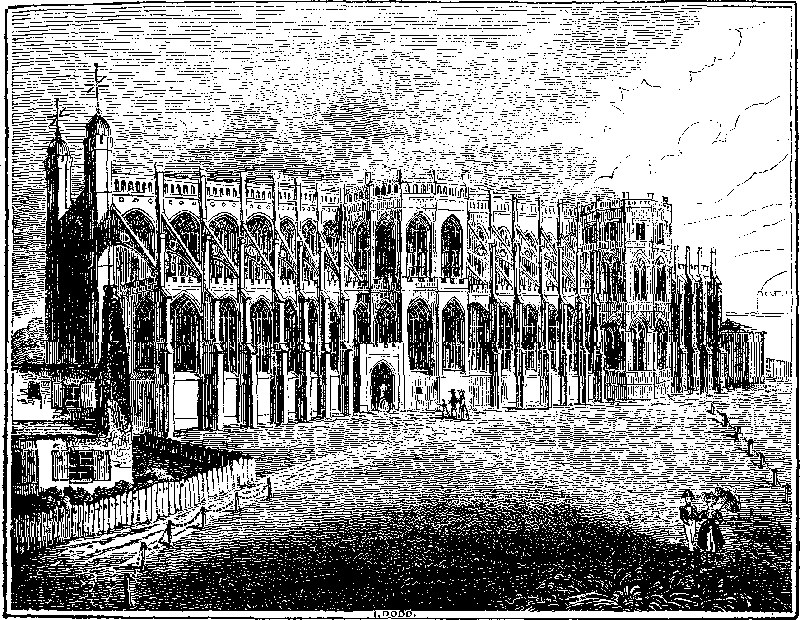

ST. GEORGE'S CHAPEL, WINDSOR.

ST. GEORGE'S CHAPEL, WINDSOR

This venerable structure, as we explained in No. 486 of The Mirror, is situated in the lower ward or court of Windsor Castle. It stands in the centre, and in a manner, divides the court into two parts. On the north or inner side are the houses and apartments of the Dean and Canons of St. George's Chapel, with those of the minor canons, clerks, and other officers; and on the south and west sides of the outer part are the houses of the Poor Knights of Windsor.

The Engraving represents the south front of the Chapel as it presents itself to the passenger through Henry the Eighth's Gateway, the principal entrance to the Lower Ward. The entrance to the Chapel, as shown in the Engraving, is that generally used, and was formed by command of George the Fourth; through which his Majesty's remains were borne, according to a wish expressed some time previous to his death.

The exterior of the Chapel requires but few descriptive details. The interior will be found in our last volume.

It is a beautiful structure, in the purest style of the Pointed architecture, and was founded by Edward the Third, in 1377, for the honour of the Order of the Garter. But however noble the first design, it was improved by Edward the Fourth and Henry the Seventh, in whose reign the famous Sir Reg. Bray, K.G., assisted in ornamenting the chapel and completing the roof. The architecture of the inside has ever been esteemed for its great beauty; and, in particular, the stone vaulting is reckoned an excellent piece of workmanship. It is an ellipsis, supported by lofty pillars, whose ribs and groins sustain the whole roof, every part of which has some different device well finished, as the arms of several of our kings, great families, &c. On each side of the choir are the stalls of the Sovereign and Knights of the Garter, with the helmet, mantling, crest, and sword of each knight, set up over his stall, on a canopy of ancient carving curiously wrought. Over the canopy is affixed the banner of each knight blazoned on silk, and on the backs of the stalls are the titles of the knights, with their arms neatly engraved and emblazoned on copper.

There are several small chapels in this edifice, in which are the monuments of many illustrious persons; particularly of Edward, Earl of Lincoln, a renowned naval warrior; George Manners, Lord Roos, and Anne, his consort, niece of Edward the Fourth; Anne, Duchess of Exeter, mother of that lady, and sister to the king; Sir Reginald Bray, before mentioned; and Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, who married the sister of King Henry the Eighth.

At the east end of St. George's Chapel is a freestone edifice, built by Henry the Seventh, as a burial-place for himself and his successors; but afterwards altering his purpose, he began the more noble structure at Westminster; and this remained neglected until Cardinal Wolsey obtained a grant of it from Henry the Eighth, and, with a profusion of expense, began here a sumptuous monument for himself, whence this building obtained the name of Wolsey's Tomb House. This monument was so magnificently built, that it exceeded that of Henry the Seventh, in Westminster Abbey; and at the time of the cardinal's disgrace, the tomb was so far executed, that Benedetto, a statuary of Florence, received 4,250 ducats for what he had already done; and 380l. 18s. had been paid for gilding only half of this monument. The cardinal dying soon after his disgrace, was buried in the cathedral at York, and the monument remained unfinished. In 1646, the statues and figures of gilt copper, of exquisite workmanship, were sold. James the Second converted this building into a Popish chapel, and mass was publicly performed here. The ceiling was painted by Verrio, and the walls were finely ornamented and painted; but the whole having been neglected since the reign of James the Second, it fell into a complete state of decay, from which, however, it was some years ago retrieved by George the Third, who had it magnificently completed (under the direction of the late James Wyatt, Esq.) in accordance with the original style, and a mausoleum constructed within, as a burial-place for the royal family.

Windsor Castle, as the reader may recollect, was magnificently re-built by William of Wykeham, who was Clerk of the Works to Edward the Third, in 1356. Little now remains of Wykeham's workmanship, save the round tower, and this has just been raised considerably. Wykeham had power to press all sorts of artificers, and to provide stone, timber, and all necessary materials for conveyance and erection. Indeed, Edward caused workmen to be impressed out of London and several counties, to the number of five or six hundred, by writs directed to the various sheriff's, who were commanded to take security of the masons and joiners, that they should not leave Windsor without permission of the architect. What a contrast are these strong measures with the scrutinized votes of money recently made for the renovation of the Castle!

ORIGIN OF THE WORD ALBION

(To the Editor.)To the elucidation of the word Britannia, contained in your 486th number, I beg to add the opinion of the same author on the subject of Albion:—

"Albion (the most ancient name of this Isle) containeth Englande and Scotlande: of the beginning (origin) of which name haue been sundrie opinios (opinions): One late feigned by him, which first prynted the Englishe Chronicle,1 wherein is neither similitude of trouth, reasone, nor honestie: I mean the fable of the fiftie doughters of Dioclesian, kyng of Syria, where neuer any other historic maketh mencion of a kyng of Syria, so named: Also that name is Greke, and no part of the language of Syria. Moreouer the coming of theim from Syria in a shippe or boate without any marynours (mariners) thorowe (through) the sea called Mediterraneum, into the occean, and so finally to finde this He, and to inhabit it, * * * * is both impossible, and much reproche to this noble Realme, to ascribe hir first name and habitation, to such inuention. Another opinion is (which hath a more honeste similitude) that it was named Albion, ab albis rupibus, of white rockes, because that unto them, that come by sea, the bankes and rockes of this He doe appeare whyte. Of this opinion I moste mervayle (marvel), because it is written of great learned men, First, Albion is no latin worde, nor hath the analogie, that is to saie, proportion or similitude of latine. For who hath founde this syllable on, at the ende of a latin woord. And if it should have bæn (been) so called for the whyte colour of the rockes, men would have called called it (I believe this to be a misprint) Alba, or Albus, or Album. In Italy were townes called Alba2 and in Asia a countrey called Albania, and neither of them took their beginning of whyte rockes, or walles, as ye may read in books of geographic: nor the water of the ryuer called Albis, semeth any whiter than other water. But if where auncient remembraunce of the beginning of thinges lacketh, it may be leeful for men to use their conjectures, than may myne be as well accepted as Plinies (although he incomparably excelled me in wisedome e doctrine) specially if it may appéer, that my coiecture (conjecture) shal approch more neere to the similitude of trouth. Wherfore I will also sett foorth mine opinion onely to the intent to exclude fables, lackyng eyther honestie or reasonable similitudes. Whan the Greekes began first to prosper, and their cities became populous, and wared puissaunt, they which trauailed on the seas, and also the yles in the seas called Hellespontus, Æigeum and Creticu (m), after that thei knewe perfectly the course of sailynge, and had founden thereby profyte, they by little and little attempted to serch and finde out the commodities of outwarde countrees: and like as Spaniardes and Portugalls haue late doone, they experienced to seeke out countries before unknown. And at laste passynge the streictes of Marrocke (Morocco) they entered into the great occean sea, where they fond (found) dyvers and many Iles. Among which they perceiuing this Ile to be not onely the greatest in circuite, but also most plenteouse of every necessary to man, the earth moste apte to bring forth," &c. The learned prelate goes on to enumerate the natural advantages of our country. He continues—"They wanderynge and reioysinge at their good and fortunate arrival, named this yle in Greeke Olbion, which in Englishe signifieth happy."

Foley Place.

AN ANTIQUARYLINES

(For the Mirror.)"Preach to the storm, or reason with despair,But tell not misery's son that life is fair"H.K. WHITE.I mark'd his eye—it beam'd with gladness,His ceaseless smile and joyous air,His infant soul had ne'er felt sadness,Nor kenn'd he yet but life was fair.His chubby cheek with genuine mirthBlown out—while all around him smiled,And fairy-land to him seemed earth,I envied him, unwitting child.I look'd again—his eye was flush'dWith passion proud and deep delight,But often o'er his brow there gush'dA blackened cloud which made it night,But still the cloud would wear away,(His youthful cheek was red and rare,)And still his heart beat light and gay,Still did he fancy life was fair.Again I looked—another change—The darkened eye, the visage wan,Told me that sorrow had been there,Told me that time had made him man.His brow was overcast, and deepHad care, the demon, furrow'd there,I heard him sigh with anguish deep,"Oh! tell me not that life is fair."COLBOURNEBIRTHPLACE OF LOCKE

(To the Editor.)The philosopher was born in the room lighted by the upper window on the right, in your Engraving No. 487. It is a small, plain apartment, having few indications of former respectability.

In the garden of Barley Wood, near Wrington, the residence of the religious and sentimental Hannah More, stands an urn commemorative of Locke, the gift of Mrs. Montague, with the following inscription:

ToJOHN LOCKE,Born in this villageThis memorial is erectedbyMrs. Montague,and presented toHANNAH MOREJ. SILVESTER

THE SELECTOR, AND LITERARY NOTICES OF NEW WORKS

A FUNERAL AT SEA

We quote the following "last scene of poor Jack's eventful history" from Capt. Basil Hall's Fragments of Voyages and Travel, a work, observes the Quarterly Review, "sure sooner or later, to be in everybody's hands."

"It need not be mentioned, that the surgeon is in constant attendance upon the dying man, who has generally been removed from his hammock to a cot, which is larger and more commodious, and is placed within a screen on one side of the sick bay, as the hospital of the ship is called. It is usual for the captain to pass through this place, and to speak to the men every morning; and I imagine there is hardly a ship in the service in which wine, fresh meat, and any other supplies recommended by the surgeon, are not sent from the tables of the captain and officers to such of the sick men as require a more generous diet than the ship's stores provided. After the carver in the gun-room has helped his messmates, he generally turns to the surgeon, and says, 'Doctor, what shall I send to the sick?' But, even without this, the steward would certainly be taken to task were he to omit inquiring, as a matter of course, what was wanted in the sick bay. The restoration of the health of the invalids by such supplies is perhaps not more important, however, than the moral influence of the attention on the part of the officers. I would strongly recommend every captain to be seen (no matter for how short a time) by the bed-side of any of his crew whom the surgeon may report as dying. Not occasionally, and in the flourishing style with which we read of great generals visiting hospitals, but uniformly and in the quiet sobriety of real kindness, as well as hearty consideration for the feelings of a man falling at his post in the service of his country. He who is killed in action has a brilliant Gazette to record his exploits, and the whole country may be said to attend his death-bed. But the merit is not less—or may even be much greater—of the soldier or sailor who dies of a fever in a distant land—his story untold, and his sufferings unseen. In warring against climates unsuited to his frame, he may have encountered, in the public service, enemies often more formidable than those who handle pike and gun. There should be nothing left undone, therefore, at such a time, to show not only to the dying man, but to his shipmates and his family at home, that his services are appreciated. I remembered, on one occasion, hearing the captain of a ship say to a poor fellow who was almost gone, that he was glad to see him so cheerful at such a moment; and begged to know if he had anything to say. 'I hope, sir,' said the expiring seaman with a smile, 'I have done my duty to your satisfaction;' 'That you have, my lad,' said his commander, 'and to the satisfaction of your country, too.' 'That is all I wanted to know, sir,' replied the man. These few commonplace words cost the captain not five minutes of his time, but were long recollected with gratitude by the people under his orders, and contributed, along with many other graceful acts of considerate attention, to fix his authority.

"If a sailor who knows he is dying, has a captain who pleases him, he is very likely to send a message by the surgeon to beg a visit—not often to trouble his commander with any commission, but merely to say something at parting. No officer, of course, would ever refuse to grant such an interview, but it appears to me it should always be volunteered; for many men may wish it, whose habitual respect would disincline them to take such a liberty, even at the moment when all distinctions are about to cease.

"Very shortly after poor Jack dies, he is prepared for his deep-sea grave by his messmates, who, with the assistance of the sailmaker, and in the presence of the master-at-arms, sew him up in his hammock, and, having placed a couple of cannon-shot at his feet, they rest the body (which now not a little resembles an Egyptian mummy) on a spare grating. Some portion of the bedding and clothes are always made up in the package—apparently to prevent the form being too much seen. It is then carried aft, and, being placed across the after-hatchway, the union jack is thrown over all. Sometimes it is placed between two of the guns, under the half deck; bat generally, I think, he is laid where I have mentioned, just abaft the mainmast. I should have mentioned before, that as soon as the surgeon's ineffectual professional offices are at an end, he walks to the quarter-deck, and reports to the officer of the watch that one of his patients has just expired. At whatever hour of the day or night this occurs, the captain is immediately made acquainted with the circumstance.

"Next day, generally about eleven o'clock, the bell on which the half-hours are struck, is tolled for the funeral, and all who choose to be present, assemble on the gangways, booms, and round the mainmast, while the forepart of the quarter-deck is occupied by the officers. In some ships—and it ought perhaps to be so in all—it is made imperative on the officers and crew to attend the ceremony. If such attendance be a proper mark of respect to a professional brother—as it surely is—it ought to be enforced, and not left to caprice. There may, indeed, be times of great fatigue, when it would harass men and officers, needlessly, to oblige them to come on deck for every funeral, and upon such occasions the watch on deck may be sufficient. Or, when some dire disease gets into a ship, and is cutting down her crew by its daily and nightly, or it maybe hourly ravages, and when, two or three times in a watch, the ceremony must be repeated, those only, whose turn it is to be on deck, need be assembled. In such fearful times, the funeral is generally made to follow close upon the death.

"While the people are repairing to the quarter-deck, in obedience to the summons of the bell, the grating on which the body is placed, being lifted from the main-deck by the messmates of the man who has died, is made to rest across the lee-gangway. The stanchions for the man-ropes of the side are unshipped, and an opening made at the after-end of the hammock netting, sufficiently large to allow a free passage. The body is still covered by the flag already mentioned, with the feet projecting a little over the gunwale, while the messmates of the deceased arrange themselves on each side. A rope, which is kept out of sight in these arrangements, is then made fast to the grating, for a purpose which will be seen presently. When all is ready, the chaplain, if there be one on board, or, if not, the captain, or any of the officers he may direct to officiate, appears on the quarter-deck and commences the beautiful service, which, though but too familiar to most ears, I have observed, never fails to rivet the attention even of the rudest and least reflecting. Of course, the bell has ceased to toll, and every one stands in silence and uncovered as the prayers are read. Sailors, with all their looseness of habits, are well disposed to be sincerely religious; and when they have fair play given them, they will always, I believe, be found to stand on as good vantage ground, in this respect, as their fellow-countrymen on shore. Be this as it may, there can be no more attentive, or apparently reverent auditory, than assembles on the deck of a ship of war, on the occasion of a shipmate's burial.

"The land service for the burial of the dead contains the following words: 'Forasmuch as it hath pleased Almighty God, of his great mercy, to take unto himself the soul of our dear brother here departed, we therefore commit his body to the ground; earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust; in sure and certain hope,' &c. Every one I am sure, who has attended the funeral of a friend—and whom will this not include?—must recollect the solemnity of that stage of the ceremony, where, as the above words are pronounced, there are cast into the grave three successive portions of earth, which, falling on the coffin, send up a hollow, mournful sound, resembling no other that I know. In the burial service at sea, the part quoted above is varied in the following very striking and solemn manner:—'Forasmuch,' &c.—'we therefore commit his body to the deep, to be turned into corruption, looking for the resurrection of the body, when the sea shall give up her dead, and the life of the world to come,' &c. At the commencement of this part of the service, one of the seamen stoops down, and disengages the flag from the remains of his late shipmate, while the others, at the words 'we commit his body to the deep,' project the grating right into the sea. The body being loaded with shot at one end, glances off the grating, plunges at once into the ocean, and—

"'In a moment, like a drop of rain,He sinks into its depths with bubbling groan,Without a grave, unknelled, uncoffined, and unknown.'"This part of the ceremony is rather less impressive than the correspondent part on land; but still there is something solemn, as well as startling, in the sudden splash, followed by the sound of the grating, as it is towed along under the main-chains.

"In a fine day at sea, in smooth water, and when all the ship's company and officers are assembled, the ceremony just described, although a melancholy one, as it must always be, is often so pleasing, all things considered, that it is calculated to leave even cheerful impressions on the mind."

(Even Captain Hall, however, admits that a sea-funeral may sometimes be a scene of unmixed sadness; and he records the following as the most impressive of all the hundreds he has witnessed. It occurred in the Leander, off the coast of North America.)

"There was a poor little middy on board, so delicate and fragile, that the sea was clearly no fit profession for him; but he or his friends thought otherwise; and as he had a spirit for which his frame was no match, he soon gave token of decay. This boy was a great favourite with every body—the sailors smiled whenever he passed, as they would have done to a child—the officers petted him, and coddled him up with all sorts of good things—and his messmates, in a style which did not altogether please him, but which he could not well resist, as it was meant most kindly, nicknamed him Dolly. Poor fellow!—he was long remembered afterwards. I forget what his particular complaint was, but he gradually sunk; and at last went out just as a taper might have done, exposed to such gusts of wind as blew in that tempestuous region. He died in the morning; but it was not until the evening that he was prepared for a seaman's grave.

"I remember, in the course of the day, going to the side of the boy's hammock, and on laying my hand upon his breast, was astonished to find it still warm—so much so, that I almost imagined I could feel the heart beat. This, of course, was a vain fancy; but I was much attached to my little companion, being then not much taller myself—and I was soothed and gratified, in a childish way, by discovering that my friend, though many hours dead, had not yet acquired the usual revolting chillness.

"In after years I have sometimes thought of this incident, when reflecting on the pleasing doctrine of the Spaniards—that as soon as children die, they are translated into angels, without any of those cold obstructions, which, they pretend, intercept and retard the souls of other mortals. The peculiar circumstances connected with the funeral which I am about to describe, and the fanciful superstitions of the sailors upon the occasion, have combined to fix the whole scene in my memory.

"Something occurred during the day to prevent the funeral taking place at the usual hour, and the ceremony was deferred till long after sunset. The evening was extremely dark, and it was blowing a treble-reefed topsail breeze. We had just sent down the top-gallant yards, and made all snug for a boisterous winter's night. As it became necessary to have lights to see what was done, several signal lanterns were placed on the break of the quarter-deck, and others along the hammock railings on the lee-gangway. The whole ship's company and officers were assembled, some on the booms, others in the boats; while the main-rigging was crowded half way up to the cat-harpings. Over-head, the mainsail, illuminated as high as the yard by the lamps, was bulging forwards under the gale, which was rising every minute, and straining so violently at the main-sheet, that there was some doubt whether it might not be necessary to interrupt the funeral in order to take sail off the ship. The lower deck ports lay completely under water, and several times the muzzles of the main-deck guns were plunged into the sea; so that the end of the grating on which the remains of poor Dolly were laid, once or twice nearly touched the tops of the waves, as they foamed and hissed past. The rain fell fast on the bare heads of the crew, dropping also on the officers, during all the ceremony, from the foot of the mainsail, and wetting the leaves of the prayer-book. The wind sighed over us amongst the wet shrouds, with a note so mournful, that there could not have been a more appropriate dirge.

"The ship—pitching violently—strained and creaked from end to end: so that, what with the noise of the sea, the rattling of the ropes, and the whistling of the wind, hardly one word of the service could be distinguished. The men, however, understood, by a motion of the captain's hand, when the time came—and the body of our dear little brother was committed to the deep.

"So violent a squall was sweeping past the ship at this moment, that no sound was heard of the usual splash, which made the sailors allege that their young favourite never touched the water at all, but was at once carried off in the gale to his final resting-place!"

THE TOPOGRAPHER

TRAVELLING NOTES IN SOUTH WALES

(For the Mirror.)Either shorePresents its combination to the viewOf all that interests, delights, enchants;—Corn-waving fields, and pastures green, and slope,And swell alternate, summits crown'd with leaf,And grave-encircled mansions, verdant capes,The beach, the inn, the farm, the mill, the path,And tinkling rivulets, and waters wide,Spreading in lake-like mirrors to the sun.N.T. CARRINGTON.Swansea Bay:—Scenery and Antiquities of GowerThe coast scenery of the western portion of Glamorgan is of singular beauty. We shall ever recall with delight our recollections of Gower, and we believe the future tourist will thank us for the outline of the more prominent beauties in the circle of the district, which we now give. Let us suppose ourselves at Swansea, and start on an excursion to the Mumbles and Caswell Bay. A road has been formed within these few years to the village of Oystermouth, about five miles from Swansea. It is perfectly level, bounded by a tram-road, and runs close to the sea-beach, forming the western side of Swansea Bay. The encroachments of the sea have been very extensive here; at high water shipping now traverse what was fifty years ago, we are told, a marshy flat, bordered by a wood near the present road, the stumps of which yet appear on the sandy beach. We have several times on riding to low water mark (about three quarters of a mile out) been nearly involved in a quick-sand adventure. Landward, the ground is broken and elevated, and thickly studded with gentlemen's seats the whole distance; many of which are embosomed in wood, and have a beautiful effect. Marino, an extensive new mansion in the Elizabethan or old English style of architecture, belonging to Mr. J.H. Vivian, and Woodlands Castle, the seat of General Warde, which is very picturesque, are particularly deserving of attention. After passing the hamlet of Norton, you near Oystermouth Castle, an extensive and splendid Gothic ruin, in fine preservation, which rears its "ivy-mantled" walls, above an eminence adjoining the road. Some suppose it to have been built by Henry de Newburgh, Earl of Warwick, in Henry the First's reign; others ascribe it on better authority to the Lords Braose, of Gower, in the reign of John; it is now the property of the Duke of Beaufort, whose care in its preservation cannot be too much commended. The inspection of this interesting ruin will repay the traveller: