полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 17, No. 483, April 2, 1831

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 17, No. 483, April 2, 1831

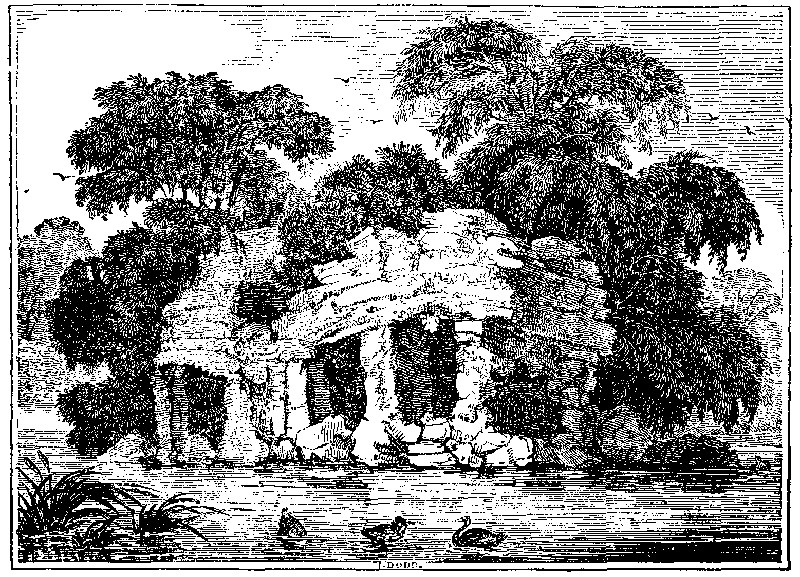

GROTTO AT ASCOT PLACE

Here is a picturesque contrivance of Art to embellish Nature. We have seen many such labours, but none with more satisfaction than the Grotto at Ascot Place.

This estate is in the county of Surrey, five miles south-east from Windsor, on the side of Ascot Heath, near Winkfield. The residence was erected by Andrew Lindergreen, Esq.; at whose death it was sold to Daniel Agace, Esq., who has evinced considerable taste in the arrangement of the grounds. The house is of brick, with wings. On the adjoining lawn, a circular Corinthian temple produces a very pleasing effect. The gem of the estate is, however, the above Grotto, which is situate at the end of a canal running through the grounds. Upon this labour of leisure much expense and good taste have been bestowed. It consists of four rooms, but one only, for the refreshing pastime of tea drinking, appears to be completed. It is almost entirely covered with a white spar, intermixed with curious and unique specimens of polished pebbles and petrifactions. The ceiling is ornamented with pendants of the same material; and the whole, when under the influence of a strong sun, has an almost magical effect. These and other decorations of the same grounds were executed by a person named Turnbull, who was employed here for several years by Mr. Agace. Our View is copied from one of a series of engravings by Mr. Hakewill, the ingenious architect; these illustrations being supplementary to that gentleman’s quarto History of Windsor.

We request the reader to enjoy with us the delightful repose—the cool and calm retreat—of the Engraving. Be he never so indifferent a lover of Nature, he must admire its picturesque beauty; or be he never so enthusiastic, he must regard with pleasure the ingenuity of the artist. To an amateur, the pursuit of decorating grounds is one of the most interesting and intellectual amusements of retirement. We have worshipped from dewy morn till dusky eve in rustic temples and “cool grots,” and have sometimes aided in their construction. The roots, limbs, and trunks of trees, and straw or reeds, are all the materials required to build these hallowed and hallowing shrines. We call them hallowing, because they are either built, or directed to be built, in adoration of the beauties of Nature; who, in turn, mantles them with endless varieties of lichens and mosses. In the Rookery adjoining John Evelyn’s “Wotton” were many such temples dedicated to sylvan deities: one of them, to Pan, consists of a pediment supported by four rough trunks of trees, the walls being of moss and laths, and enclosed with tortuous limbs. Beneath the pediment is the following apposite line from Virgil:

Pan curat oves oviumque magistros.Pan, guardian of the sheep and shepherds too.Yet the building is not merely ornamental, for the back serves as a cow-house!

Pope’s love of grotto-building has made it a poetical amusement. Who does not remember his grotto at Twickenham—

The EGERIAN GROT,Where, nobly pensive, ST. JOHN sat and thought;Where British sighs from dying Wyndham stole,And the bright flame was shot through Marchmont’s soul.Let such, such only, tread this sacred floor,Who dare to love their COUNTRY, and be poor.—The Grotto, has, however, crumbled to the dilapidations of time, and the pious thefts of visiters; but, proud are we to reflect that the poetry of the great genius who dictated its erection—LIVES; and his fame is untarnished by the canting reproach of the critics of our time. True it is that the best, or ripest fruit, is always most pecked at.

FAIRY SONG

(For the Mirror.)Slowly o’er the mountain’s browRosy light is dawning;See! the stars are fading nowIn the beam of morning.Yonder soft approaching rayBids us, Fairies, haste away.Fairy guardians, watching o’erFlowers of tender blossom,Chilling damps descend no more,And the flow’ret’s bosom,Opening to th’ approaching day,Bids ye, Fairies, haste away.Hark! the lonely bird of nightStays its notes of sadness;Early birds, that hail the light,Soon shall wake to gladness.Philomel’s concluding layBids us follow night away.Ye that guard the infant’s rest,Or watch the maiden’s pillow;—Demons seek their home unblest’Neath Ocean’s deepest billow:Harmless now the dreams that playO’er slumbering eyes, then haste away.Farewell lovely scenes, that hereWait the day god’s shining;We must follow Dian’s sphereO’er the hills declining.Brighter comes the beam of day—Haste ye, Fairies, haste away.G.J.DREAMS PRODUCED BY WHISPERING IN THE SLEEPER’S EAR

(For the Mirror)Dreams are but interludes which fancy makes;When monarch Reason sleeps, this mimic wakes.DRYDEN.Dr. Abercrombie, in his work on the Intellectual Powers, has recorded several instances of remarkable dreams.—Among them is the following extraordinary instance of the power which may be exercised over some persons while asleep, of creating dreams by whispering in their ears. An officer in the expedition to Lanisburg, in 1758, had this peculiarity in so remarkable a degree, that his companions in the transport were in the constant habit of amusing themselves at his expense. It had more effect when the voice was that of a friend familiar to him. At one time they conducted him through the whole progress of a quarrel, which ended in a duel, and when the parties were supposed to be met, a pistol was put into his hand, which he fired, and was awakened by the report. On another occasion they found him asleep on the top of a locker, or bunker, in the cabin, when they made him believe he had fallen overboard, and exhorted him to save himself by swimming. They then told him a shark was pursuing him, and entreated him to dive for his life; this he instantly did, but with such force as to throw himself from the locker to the cabin floor, by which he was much bruised, and awakened of course. After the landing of the army at Lanisburg, his companions found him one day asleep in the tent, and evidently much annoyed by the cannonading. They then made him believe he was engaged, when he expressed great fear, and an evident disposition to run away. Against this they remonstrated, but at the same time increased his fears by imitating the groans of the wounded and the dying; and when he asked, as he sometimes did, who were down, they named his particular friends. At last they told him that the man next him in the line had fallen, when he instantly sprang from his bed, rushed out of the tent, and was roused from his danger and his dream together, by falling over the tent ropes.

By the by, all this is quite contrary to Dryden’s theory, who says—

“As one who in a frightful dream would shunHis pressing foe, labours in vain to run;And his own slowness in his sleep bemoans,With thick short sighs, weak cries, and tender groans.”And again, in his Virgil—

“When heavy sleep has closed the sight,And sickly fancy labours in the night,We seem to run, and, destitute of force,Our sinking limbs forsake us in the course;In vain we heave for breath—in vain we cry—The nerves unbraced, their usual strength deny,And on the tongue the flattering accents die.”Now this man seems to have had the use not only of his limbs, but of his faculty of speech, while dreaming; and it was not till after he awoke that he felt the oppression Dryden describes; for it is stated, that when he awoke he had no distinct recollection of his dream, but only a confused feeling of oppression and fatigue, and used to tell his companions that he was sure they had been playing some trick upon him.

W.A.R.

P.S. This is a sleepy article; and I would warn its reader to endeavour not to fall asleep over it, and thus endanger his falling over his chair; and lest some familiar friend or chere amie should, finding his instructions in his hand, take the opportunity of making the experiment, and may be create a little jealous quarrel or so.

SONNET TO THE RIVER ARUN

(For the Mirror.)Pure Stream! whose waters gently glide along,In murmuring cadence to the Poet’s ear,Who, stretch’d at ease your flowery banks among,Views with delight your glassy surface clear,Roll pleasing on through Otways sainted wood;Where “musing Pity” still delights to mourn,And kiss the spot where oft her votary stood,Or hang fresh cypress o’er his weeping urn;—Here, too, retir’d from Folly’s scenes afar,His powerful shell first studious Collins strung;Whilst Fancy, seated in her rainbow car,Round him her flowers Parnassian wildly flung.Stream of the Bards! oft Hayley linger’d here;And Charlotte Smith1 hath grac’d thy current with a tear.The Author of “A Tradesman’s Lays.” No. 85, Leather Lane.RETROSPECTIVE GLEANINGS

ANCIENT BLACK BOOKS, &c

(For the Mirror.)The Black Book of the Exchequer is said to have been composed in the year 1175, by Gervase of Tilbury, nephew of King Henry the Second. It contains a description of the court of England, as it then stood, its officers, their ranks, privileges, wages, perquisites, powers, and jurisdictions; and the revenues of the crown, both in money, grain, and cattle. Here we find, that for one shilling, as much bread might be bought as would serve a hundred men a whole day; and the price for a fat bullock was only twelve shillings, and a sheep four, &c. At the end of this book are the Annals of William of Worcester, which contain notes on the affairs of his own times.

The Black Book of the English Monasteries was a detail of the scandalous enormities practised in religious houses: compiled by order of the visiters, under King Henry the Eighth, to blacken them, and thus hasten their dissolution.

Books which relate to necromancy are called Black Books.

Black-rent, or Black-mail, was a certain rate of money, corn, cattle, or other consideration, paid (says Cowell) to men allied with robbers, to be by them protected from the danger of such as usually rob or steal.

P.T.W.

ANCIENT STATE OF PANCRAS

(For the Mirror.)Brewer, in his “London and Middlesex,” says—“When a visitation of the church of Pancras was made, in the year 1251, there were only forty houses in the parish.” The desolate situation of the village, in the latter part of the 16th century, is emphatically described by Norden, in his “Speculum Britanniæ.” After noticing the solitary condition of the church, he says—“Yet about the structure have bin manie buildings, now decaied, leaving poore Pancrast without companie or comfort.” In some manuscript additions to his work, the same writer has the following observations:—“Although this place be, as it were, forsaken of all, and true men seldom frequent the same, but upon deveyne occasions, yet it is visayed by thieves, who assemble not there to pray, but to waite for prayer; and many fall into their handes, clothed, that are glad when they are escaped naked. Walk not there too late.”

Pancras is said to have been a parish before the Conquest, and is mentioned in Domesday Book. It derived its name from the saint to whom the church is dedicated—a youthful Phrygian nobleman, who suffered death under the Emperor Dioclesian, for his adherence to the Christian faith.

P.T.W.

SALT AMONG THE ANCIENT GREEKS

(For the Mirror.)Potter, in his “Antiquities of Greece,” says—“Salt was commonly set before strangers, before they tasted the victuals provided for them; whereby was intimated, that as salt does consist of aqueous and terrene particles, mixed and united together, or as it is a concrete of several aqueous parts, so the stranger and the person by whom he was entertained should, from the time of their tasting salt together, maintain a constant union of love and friendship.”

Others tell us, that salt being apt to preserve flesh from corruption, signified, that the friendship which was then begun should be firm and lasting; and some, to mention no more different opinions concerning this matter, think, that a regard was had to the purifying quality of salt, which was commonly used in lustrations, and that it intimated that friendship ought to be free from all design and artifice, jealousy and suspicion.

It may be, the ground of this custom was only this, that salt was constantly used at all entertainments, both of the gods and men, whence a particular sanctity was believed to be lodged in it: it is hence called divine salt by Homer, and holy salt by others; and by placing of salt on the table, a sort of blessing was thought to be conveyed to them. To have eaten at the same table was esteemed an inviolable obligation to friendship; and to transgress the salt at the table—that is, to break the laws of hospitality, and to injure one by whom any person had been entertained—was accounted one of the blackest crimes: hence that exaggerating interrogation of Demosthenes, “Where is the salt? where the hospital tables?” for in despite of these, he had been the author of these troubles. And the crime of Paris in stealing Helena is aggravated by Cassandra, upon this consideration, that he had contemned the salt, and overturned the hospital table.

P.T.W.

THE NOVELIST

THE GAMESTER’S DAUGHTER

From the Confessions of an Ambitious StudentA fit, one bright spring morning, came over me—a fit of poetry. From that time the disorder increased, for I indulged it; and though such of my performances as have been seen by friendly eyes have been looked upon as mediocre enough, I still believe, that if ever I could win a lasting reputation, it would be through that channel. Love usually accompanies poetry, and, in my case, there was no exception to the rule.

“There was a slender, but pleasant brook, about two miles from our house, to which one or two of us were accustomed, in the summer days, to repair to bathe and saunter away our leisure hours. To this favourite spot I one day went alone, and crossing a field which led to the brook, I encountered two ladies, with one of whom, having met her at some house in the neighbourhood, I had a slight acquaintance. We stopped to speak to each other, and I saw the face of her companion. Alas! were I to live ten thousand lives, there would never be a moment in which I could be alone—nor sleeping, and that face not with me!

“My acquaintance introduced us to each other. I walked home with them to the house of Miss D–(so was the strange, who was also the younger lady named.) The next day I called upon her; the acquaintance thus commenced did not droop; and, notwithstanding our youth—for Lucy D– was only seventeen, and I nearly a year younger—we soon loved, and with a love, which, full of poesy and dreaming, as from our age it necessarily must have been, was not less durable, nor less heart-felt, than if it had arisen from the deeper and more earthly sources in which later life only hoards its affections.

“Oh, God! how little did I think of what our young folly entailed upon us! We delivered ourselves up to the dictates of our hearts, and forgot that there was a future. Neither of us had any ulterior design; we did not think—poor children that we were—of marriage, and settlements, and consent of relations. We touched each other’s hands, and were happy; we read poetry together—and when we lifted up our eyes from the page, those eyes met, and we did not know why our hearts beat so violently; and at length, when we spake of love, and when we called each other Lucy and –; when we described all that we had thought in absence—and all we had felt when present—when we sat with our hands locked each in each—and at last, growing bolder, when in the still and quiet loneliness of a summer twilight we exchanged our first kiss, we did not dream that the world forbade what seemed to us so natural; nor—feeling in our own hearts the impossibility of change—did we ever ask whether this sweet and mystic state of existence was to last for ever!

“Lucy was an only child; her father was a man of wretched character. A profligate, a gambler—ruined alike in fortune, hope, and reputation, he was yet her only guardian and protector. The village in which we both resided was near London; there Mr. D– had a small cottage, where he left his daughter and his slender establishment for days, and sometimes for weeks together, while he was engaged in equivocal speculations—giving no address, and engaged in no professional mode of life. Lucy’s mother had died long since, of a broken heart—(that fate, too, was afterwards her daughter’s)—so that this poor girl was literally without a monitor or a friend, save her own innocence—and, alas! innocence is but a poor substitute for experience. The lady with whom I had met her had known her mother, and she felt compassion for the child. She saw her constantly, and sometimes took her to her own house, whenever she was in the neighbourhood; but that was not often, and only for a few days at a time. Her excepted, Lucy had no female friend.

“One evening we were to meet at a sequestered and lonely part of the brook’s course, a spot which was our usual rendezvous. I waited considerably beyond the time appointed, and was just going sorrowfully away when she appeared. As she approached, I saw that she was in tears—and she could not for several moments speak for weeping. At length I learned that her father had just returned home, after a long absence—that he had announced his intention of immediately quitting their present home and going to a distant part of the country, or—perhaps even abroad.

“It is an odd thing in the history of the human heart, that the times most sad to experience are often the most grateful to recall; and of all the passages in our brief and checkered love, none have I clung to so fondly or cherished so tenderly, as the remembrance of that desolate and tearful hour. We walked slowly home, speaking very little, and lingering on the way—and my arm was round her waist all the time. There was a little stile at the entrance of the garden round Lucy’s home, and sheltered as it was by trees and bushes, it was there, whenever we met, we took our last adieu—and there that evening we stopped, and lingered over our parting words and our parting kiss—and at length, when I tore myself away, I looked back and saw her in the sad and grey light of the evening still there, still watching, still weeping! What, what hours of anguish and gnawing of heart must one, who loved so kindly and so entirely as she did, have afterwards endured.

“As I lay awake that night, a project, natural enough, darted across me. I would seek Lucy’s father, communicate our attachment, and sue for his approbation. We might, indeed, be too young for marriage—but we could wait, and love each other in the meanwhile. I lost no time in following up this resolution. The next day, before noon, I was at the door of Lucy’s cottage—I was in the little chamber that faced the garden, alone with her father.

“A boy forms strange notions of a man who is considered a scoundrel. I was prepared to see one of fierce and sullen appearance, and to meet with a rude and coarse reception. I found in Mr. D– a person who early accustomed—(for he was of high birth)—to polished society, still preserved, in his manner and appearance, its best characteristics. His voice was soft and bland; his face, though haggard and worn, retained the traces of early beauty; and a courteous and attentive ease of deportment had been probably improved by the habits of deceiving others, rather than impaired. I told our story to this man, frankly and fully. When I had done, he rose; he took me by the hand; he expressed some regret, yet some satisfaction, at what he had heard. He was sensible how much peculiar circumstances had obliged him to leave his daughter unprotected; he was sensible, also, that from my birth and future fortunes, my affection did honour to the object of my choice. Nothing would have made him so happy, so proud, had I been older—had I been my own master. But I and he, alas! must be aware that my friends and guardians would never consent to my forming any engagement at so premature an age, and they and the world would impute the blame to him; for calumny (he added in a melancholy tone) had been busy with his name, and any story, however false or idle, would be believed of one who was out of the world’s affections.

“All this, and much more, did he say; and I pitied him while he spoke. Our conference then ended in nothing fixed;—but—he asked me to dine with him the next day. In a word, while he forbade me at present to recur to the subject, he allowed me to see his daughter as often as I pleased: this lasted for about ten days. At the end of that time, when I made my usual morning visit, I saw D– alone; he appeared much agitated. He was about, he said, to be arrested. He was undone for ever—and his poor daughter!—he could say no more—his manly heart was overcome—and he hid his face with his hands. I attempted to console him, and inquired the sum necessary to relieve him. It was considerable; and on hearing it named, my power of consolation I deemed over at once. I was mistaken. But why dwell on so hacknied a topic as that of a sharper on the one hand, and a dupe on the other? I saw a gentleman of the tribe of Israel—I raised a sum of money, to be repaid when I came of age, and that sum was placed in D–‘s hands. My intercourse with Lucy continued; but not long. This matter came to the ears of one who had succeeded my poor aunt, now no more, as my guardian. He saw D–, and threatened him with penalties, which the sharper did not dare to brave. My guardian was a man of the world; he said nothing to me on the subject, but he begged me to accompany him on a short tour through a neighbouring county. I took leave of Lucy only for a few days as I imagined. I accompanied my guardian—was a week absent—returned—and hastened to the cottage; it was shut up—an old woman opened the door—they were gone, father and daughter, none knew whither!

“It was now that my guardian disclosed his share in this event, so terribly unexpected by me. He unfolded the arts of D–; he held up his character in its true light. I listened to him patiently, while he proceeded thus far; but when, encouraged by my silence, he attempted to insinuate that Lucy was implicated in her father’s artifices—that she had lent herself to decoy, to the mutual advantage of sire and daughter, the inexperienced heir of considerable fortunes,—my rage and indignation exploded at once. High words ensued. I defied his authority—I laughed at his menaces—I openly declared my resolution of tracing Lucy to the end of the world, and marrying her the instant she was found. Whether or not that my guardian had penetrated sufficiently into my character to see that force was not the means by which I was to be guided, I cannot say; but he softened from his tone at last—apologized for his warmth—condescended to soothe and remonstrate—and our dispute ended in a compromise. I consented to leave Mr. S–, and to spend the next year, preparatory to my going to the university, with my guardian: he promised, on the other hand, that if, at the end of that year, I still wished to discover Lucy, he would throw no obstacles in the way of my search. I was ill-contented with this compact; but I was induced to it by my firm persuasion that Lucy would write to me, and that we should console each other, at least, by a knowledge of our mutual situation and our mutual constancy. In this persuasion, I insisted on remaining six weeks longer with S–, and gained my point; and that any letter Lucy might write, might not be exposed to any officious intervention from S–, or my guardian’s satellites, I walked every day to meet the postman who was accustomed to bring our letters. None came from Lucy. Afterwards, I learned that D–, whom my guardian had wisely bought, as well as intimidated, had intercepted three letters which she had addressed to me, in her unsuspecting confidence—and that she only ceased to write when she ceased to believe in me.

“I went to reside with my guardian. A man of a hospitable and liberal turn, his house was always full of guests, who were culled from the most agreeable circles in London. We lived in a perpetual round of amusement; and my uncle, who thought I should be rich enough to afford to be ignorant, was more anxious that I should divert my mind, than instruct it. Well, this year passed slowly and sadly away, despite of the gaiety around me; and, at the end of that time, I left my uncle to go to the university; but I first lingered in London to make inquiries after D–. I could learn no certain tidings of him, but heard that the most probable place to find him was a certain gaming-house in K– Street. Thither I repaired forthwith. It was a haunt of no delicate and luxurious order of vice; the chain attached to the threshold indicated suspicion of the spies of justice; and a grim and sullen face peered jealously upon me before I was suffered to ascend the filthy and noisome staircase. But my search was destined to a brief end. At the head of the Rouge et Noir table, facing my eyes the moment I entered the evil chamber, was the marked and working countenance of D–.