полная версия

полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 2

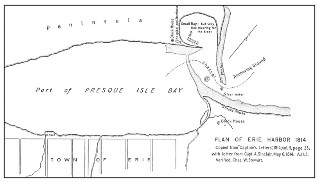

From point to point the mouth of the harbor, where the outer bar occurs, was eight tenths of a mile wide. As shown by a sketch of the period, the distance to be travelled on the floats, from deep water within to deep water without, was a mile; rather less than more. On Monday morning, August 2, the movement of the vessels began simultaneously. Five of the smaller, which under usual conditions could pass without lightening, were ordered to cross and take positions outside, covering the channel; a sixth, with the "Niagara," were similarly posted within. The protection thus afforded was re-enforced by three 12-pounder long guns, mounted on the beach, abreast the bar; distant not over five hundred yards from the point where the channel issued on the lake. While these dispositions were being made, the "Lawrence's" guns were hoisted out, and placed in boats to be towed astern of her; the floats taken alongside, filled, sunk, and made fast, so that when pumped out their rising would lift the brig. In the course of these preparations it was found that the water had fallen to four feet, so that even the schooners had to be lightened, while the transit of the "Lawrence" was rendered more tedious and difficult. The weather, however, was propitious, with a smooth lake; and although the brig grounded in the shoalest spot, necessitating a second sinking of the burden-bearing floats,—appropriately called "camels,"—perseverance protracted through that night and the day of the 3d carried her outside. At 8 A.M. of the 4th she was fairly afloat. Guns, singly light in weight as hers were, were quickly hoisted on board and mounted; but none too soon, for the enemy appeared almost immediately. The "Niagara's" passage was more easily effected, and Barclay offered no molestation. In a letter to the Department, dated August 4, 1813, 9 P.M., Perry reported, "I have great pleasure in informing you that I have succeeded in getting over the bar the United States vessels, the 'Lawrence,' 'Niagara,' 'Caledonia,' 'Ariel,' 'Scorpion,' 'Somers,' 'Tigress,' and 'Porcupine.'" He added, "The enemy have been in sight all day." The vessels named, with the schooner "Ohio" and the sloop "Trippe," constituted the entire squadron.

PLAN OF ERIE HARBOR 1814

While Perry was thus profitably employed, Procter had embarked on another enterprise against the magazines on the American front of operations. His intention, as first reported to Prevost, was to attack Sandusky; but the conduct of the Indians, upon the co-operation of whom he had to rely, compelled him to diverge to Fort Meigs. Here the savages began to desert, an attempt to draw the garrison into an ambush having failed; and when Procter, after two days' stay, determined to revert to Sandusky, he was accompanied by "as many hundred of them as there should have been thousands." The white troops went on by water, the Indians by the shore. They appeared before Fort Stephenson on Sunday, August 1. The garrison was summoned, with the customary intimation of the dire consequences to be apprehended from the savages in case of an assault. The American commander, Major Croghan, accepted these possibilities, and the following day, during which the "Lawrence" was working her way over Erie bar, the artillery and the guns of the gunboats were busy battering the northwest angle of the fort. At 4 P.M. an assault was made. It was repelled with heavy loss to the assailants, and little to the besieged. That night the baffled enemy withdrew to Malden.

The American squadron having gained the lake and mounted its batteries, Barclay found himself like Chauncey while awaiting the "General Pike." His new and most powerful vessel, the ship "Detroit," was approaching completion. He was now too inferior in force to risk action when he might expect her help so soon, and he therefore retired to Malden. Perry was thus left in control of Lake Erie. He put out on August 6; but, failing to find the enemy, he anchored again off Erie, to take on board provisions, and also stores to be carried to Sandusky for the army. While thus occupied, there came on the evening of the 8th the welcome news that a re-enforcement of officers and seamen was approaching. On the 10th, these joined him to the number of one hundred and two. At their head was Commander Jesse D. Elliott, an officer of reputation, who became second in command to Perry, and took charge of the "Niagara."

On August 12 the squadron finally made sail for the westward, not to return to Erie till the campaign was decided. Its intermediate movements possess little interest, the battle of Lake Erie being so conspicuously the decisive incident as to reduce all preceding it to insignificance. Perry was off Malden on August 25, and again on September 1. The wind on the latter day favoring movement both to go and come, a somewhat rare circumstance, he remained all day reconnoitring near the harbor's mouth. The British squadron appeared complete in vessels and equipment; but Barclay had his own troubles about crews, as had his antagonist, his continual representations to Yeo meeting with even less attention than Perry conceived himself to receive from Chauncey. He was determined to postpone action until re-enforcements of seamen should arrive from the eastward, unless failure of provisions, already staring him in the face, should force him to battle in order to re-establish communications by the lake.

The headquarters of the United States squadron was at Put-in Bay, in the Bass Islands, a group thirty miles southeast of Malden. The harbor was good, and the position suitable for watching the enemy, in case he should attempt to pass eastward down the lake, towards Long Point or elsewhere. Hither Perry returned on September 6, after a brief visit to Sandusky Bay, where information was received that the British leaders had determined that the fleet must, at all hazards, restore intercourse with Long Point. From official correspondence, afterwards captured with Procter's baggage, it appears that the Amherstburg and Malden district was now entirely dependent for flour upon Long Point, access to which had been effectually destroyed by the presence of the American squadron. Even cattle, though somewhat more plentiful, could no longer be obtained in the neighborhood in sufficient numbers, owing to the wasteful way in which the Indians had killed where they wanted. They could not be restrained without alienating them, or, worse, provoking them to outrage. Including warriors and their families, fourteen thousand were now consuming provisions. In the condition of the roads, only water transport could meet the requirements; and that not by an occasional schooner running blockade, but by the free transit of supplies conferred by naval control. To the decision to fight may have been contributed also a letter from Prevost, who had been drawn down from Kingston to St. David's, on the Niagara frontier, by his anxiety about the general situation, particularly aroused by Procter's repulse from Fort Stephenson. Alluding to the capture of Chauncey's two schooners on August 10, he wrote Procter on the 22d, "Yeo's experience should convince Barclay that he has only to dare and he will be successful."83 It was to be Sir George's unhappy lot, a year later, to goad the British naval commander on Lake Champlain into premature action; and there was ample time for the present indiscreet innuendo to reach Barclay, and impel him to a step which Prevost afterwards condemned as hasty, because not awaiting the arrival of a body of fifty seamen announced to be at Kingston on their way to Malden.

At sunrise of September 10, the lookout at the masthead of the "Lawrence" sighted the British squadron in the northwest. Barclay was on his way down the lake, intending to fight. The wind was southwest, fair for the British, but adverse to the Americans quitting the harbor by the channel leading towards the enemy. Fortunately it shifted to southeast, and there steadied; which not only enabled them to go out, but gave them the windward position throughout the engagement. The windward position, or weather gage, as it was commonly called, conferred the power of initiative; whereas the vessel or fleet to leeward, while it might by skill at times force action, or itself obtain the weather gage by manœuvring, was commonly obliged to await attack and accept the distance chosen by the opponent. Where the principal force of a squadron, as in Perry's case, consists in two vessels armed almost entirely with carronades, the importance of getting within carronade range is apparent.

Looking forward to a meeting, Perry had prearranged the disposition of his vessels to conform to that which he expected the enemy to assume. Unlike ocean fleets, all the lake squadrons, as is already known of Ontario, were composed of vessels very heterogeneous in character. This was because the most had been bought, not designed for the navy. It was antecedently probable, therefore, that a certain general principle would dictate the constitution of the three parts of the order of battle, the centre and two flanks, into which every military line divides. The French have an expression for the centre,—corps de bataille,—which was particularly appropriate to squadrons like those of Barclay and Perry. Each had a natural "body of battle," in vessels decisively stronger than all the others combined. This relatively powerful division would take the centre, as a cohesive force, to prevent the two ends—or flanks—being driven asunder by the enemy. Barclay's vessels of this class were the new ship, "Detroit," and the "Queen Charlotte;" Perry's were the "Lawrence" and "Niagara." Each had an intermediate vessel; the British the "Lady Prevost," the Americans the "Caledonia." In addition to these were the light craft, three British and six Americans; concerning which it is to be said that the latter were not only the more numerous, but individually much more powerfully armed.

The same remark is true, vessel for vessel, of those opposed to one another by Perry's plan; that is, measuring the weight of shot discharged at a broadside, which is the usual standard of comparison, the "Lawrence" threw more metal than the "Detroit," the "Niagara" much more than the "Queen Charlotte," and the "Caledonia," than the "Lady Prevost." This, however, must be qualified by the consideration, more conspicuously noticeable on Ontario than on Erie, of the greater length of range of the long gun. This applies particularly to the principal British vessel, the "Detroit." Owing to the difficulties of transportation, and the demands of the Ontario squadron, her proper armament had not arrived. She was provided with guns from the ramparts of Fort Malden, and a more curiously composite battery probably never was mounted; but, of the total nineteen, seventeen were long guns. It is impossible to say what her broadside may have weighed. All her pieces together fired two hundred and thirty pounds, but it is incredible that a seaman like Barclay should not so have disposed them as to give more than half that amount to one broadside. That of the "Lawrence," was three hundred pounds; but all her guns, save two twelves, were carronades. Compared with the "Queen Charlotte," the battery of the "Niagara" was as 3 to 2; both chiefly carronades.

From what has been stated, it is evident that if Perry's plan were carried out, opposing vessel to vessel, the Americans would have a superiority of at least fifty per cent. Such an advantage, in some quarter at least, is the aim of every capable commander; for the object of war is not to kill men, but to carry a point: not glory by fighting, but success in result. The only obvious dangers were that the wind might fail or be very light, which would unduly protract exposure to long guns before getting within carronade range; or that, by some vessels coming tardily into action, one or more of the others would suffer from concentration of the enemy's fire. It was this contingency, realized in fact, which gave rise to the embittered controversy about the battle; a controversy never settled, and probably now not susceptible of settlement, because the President of the United States, Mr. Monroe, pigeonholed the charges formulated by Perry against Elliott in 1818. There is thus no American sworn testimony to facts, searched and sifted by cross-examination; for the affidavits submitted on the one side and the other were ex parte, while the Court of Inquiry, asked by Elliott in 1815, neglected to call all accessible witnesses—notably Perry himself. In fact, there was not before it a single commanding officer of a vessel engaged. Such a procedure was manifestly inadequate to the requirement of the Navy Department's letter to the Court, that "a true statement of the facts in relation to Captain Elliott's conduct be exhibited to the world." Investigation seems to have been confined to an assertion in a British periodical, based upon the proceedings of the Court Martial upon Barclay, to the effect that Elliott's vessel "had not been engaged, and was making away,"84 at the time when Perry "was obliged to leave his ship, which soon after surrendered, and hoist his flag on board another of his squadron." The American Court examined two officers of Perry's vessel, and five of Elliott's; no others. To the direct question, "Did the 'Niagara' at any time during the action attempt to make off from the British fleet?" all replied, "No." The Court, therefore, on the testimony before it, decided that the charge "made in the proceedings85 of the British Court Martial … was malicious, and unfounded in fact;" expressing besides its conviction "that the attempts to wrest from Captain Elliott the laurels he gained in that splendid victory … ought in no wise to lessen him in the opinion of his fellow citizens as a brave and skilful officer." At the same time it regretted that "imperious duty compelled it to promulgate testimony which appears materially to differ in some of its most important points."

In this state the evidence still remains, owing to the failure of the President to take action, probably with a benevolent desire to allay discord, and envelop facts under a kindly "All's well that ends well." Perry died a year after making his charges, which labored under the just imputation that he had commended Elliott in his report, and again immediately afterwards, though in terms that his subordinate thought failed to do him justice. American naval opinion divided, apparently in very unequal numbers. Elliott's officers stood by him, as was natural; for men feel themselves involved in that which concerns the conduct of their ship, and see incidents in that light. Perry's officers considered that the "Lawrence" had not been properly supported; owing to which, after losses almost unparalleled, she had to undergo the mortification of surrender. Her heroism, her losses, and her surrender, were truths beyond question.

The historian to-day thus finds himself in the dilemma that the American testimony is in two categories, distinctly contradictory and mutually destructive; yet to be tested only by his own capacity to cross-examine the record, and by reference to the British accounts. The latter are impartial, as between the American parties; their only bias is to constitute a fair case for Barclay, by establishing the surrender of the American flagship and the hesitancy of the "Niagara" to enter into action. This would indicate victory so far, changed to defeat by the use Perry made of the vessel preserved to him intact by the over-caution of his second. Waiving motives, these claims are substantially correct, and constitute the analysis of the battle as fought and won.

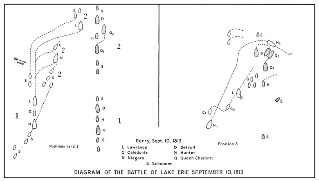

Barclay, finding the wind to head him and place him to leeward, arranged his fleet to await attack in the following order, from van to rear: The schooner "Chippewa," "Detroit," "Hunter," "Queen Charlotte," "Lady Prevost," "Little Belt."86 This, he said in his official letter, was "according to a given plan, so that each ship [that is, the "Detroit" and "Queen Charlotte"] might be supported against the superior force of the two brigs opposed to them." The British vessels lay in column, in each other's wake, by the wind on the port tack, hove-to (stopped) with a topsail to the mast, heading to the southwest (position 1). Perry now modified some details of his disposition. It had been expected that the "Queen Charlotte" would precede the "Detroit," and the American commander had therefore placed the "Niagara" leading, as designated to fight the "Charlotte," the "Lawrence" following the "Niagara." This order was now reversed, and the "Caledonia" interposed between the two; the succession being "Lawrence," "Caledonia," "Niagara." Having more schooners than the enemy, he placed in the van two of the best, the "Scorpion" and the "Ariel"; the other four behind the "Niagara." His centre, therefore, the "Lawrence," "Caledonia," and "Niagara," were opposed to the "Detroit," "Hunter," and "Queen Charlotte." The long guns of the "Ariel," "Scorpion," and "Caledonia" supplied in measure the deficiency of gun power in the "Lawrence," while standing down outside of carronade range; the "Caledonia," with the rear schooners, giving a like support to the "Niagara." The "Ariel," and perhaps also the "Scorpion," was ordered to keep a little to windward of the "Lawrence." This was a not uncommon use of van vessels, making more hazardous any attempt of the opponent to tack and pass to windward, in order to gain the weather gage with its particular advantages (position 1).

The rear four schooners, as is frequently the case in long columns, were straggling somewhat at the time the signal to bear down was made; and they had difficulty in getting into action, being compelled to resort to the sweeps because the wind was light. It is not uncommon to see small vessels with low sails thus retarded, while larger are being urged forward by their lofty light canvas. The line otherwise having been formed, Perry stood down without regard to them. At quarter before noon the "Detroit" opened upon the "Lawrence" with her long guns. Ten minutes later the Americans began to reply. Finding the British fire at this range more destructive than he had anticipated, Perry made more sail upon the Lawrence. Word had already been passed by hail of trumpet to close up in the line, and for each vessel to come into action against her opponent, before designated. The "Lawrence" continued thus to approach obliquely, using her own long twelves, and backed by the long guns of the vessels ahead and astern, till she was within "canister range," apparently about two hundred and fifty yards, when she turned her side to the wind on the weather quarter of the "Detroit," bringing her carronade battery to bear (position 2). This distance was greater than desirable for carronades; but with a very light breeze, little more than two miles an hour, there was a limit to the time during which it was prudent to allow an opponent's raking fire to play, unaffected in aim by any reply. Moreover, much of her rigging was already shot away, and she was becoming unmanageable. The battle was thus joined by the commander-in-chief; but, while supported to his satisfaction by the "Scorpion" and "Ariel" ahead, and "Caledonia" astern, with their long guns, the "Niagara" did not come up, and her carronades failed to do their share. The captain of her opponent, the "Queen Charlotte," finding that his own carronades would not reach her, made sail ahead, passed the "Hunter," and brought his battery to the support of the "Detroit" in her contest with the "Lawrence" (Q2). Perry's vessel thus found herself under the combined fire of the "Detroit," "Queen Charlotte," and in some measure of the "Hunter"; the armament of the last, however, was too trivial to count for much.

Elliott's first placing of the "Niagara" may, or may not, have been judicious as regards his particular opponent. The "Queen Charlotte's" twenty-fours would not reach him; and it may be quite proper to take a range where your own guns can tell and your enemy's cannot. Circumstance must determine. The precaution applicable in a naval duel may cease to be so when friends are in need of assistance; and when the British captain, seeing how the case stood, properly and promptly carried his ship forward to support his commander, concentrating two vessels upon Perry's one, the situation was entirely changed. The plea set up by Cooper, who fought Elliott's battle conscientiously, but with characteristic bitterness as well as shrewdness, that the "Niagara's" position, assigned in the line behind the "Caledonia," could not properly be left without signal, practically surrenders the case. It is applying the dry-rot system of fleet tactics in the middle of the eighteenth century to the days after Rodney and Nelson, and is further effectually disposed of by the consentient statement of several of the American captains, that their commander's dispositions were made with reference to the enemy's order; that is, that he assigned a special enemy's ship to a special American, and particularly the "Detroit" to the "Lawrence," and the "Queen Charlotte" to the "Niagara." The vessels of both fleets being so heterogeneous, it was not wise to act as with units nearly homogeneous, by laying down an order, the governing principle of which was mutual support by a line based upon its own intrinsic qualities. The considerations dictating Perry's dispositions were external to his fleet, not internal; in the enemy's order, not in his own. This was emphasized by his changing the previously arranged stations of the "Lawrence" and the "Niagara," when he saw Barclay's line. Lastly, he re-enforced all this by quoting to his subordinates Nelson's words, that no captain could go very far wrong who placed his vessel close alongside those of the enemy.

DIAGRAM OF THE BATTLE OF LAKE ERIE SEPTEMBER 10, 1813

Cooper, the ablest of Elliott's champions, has insisted so strongly upon the obligation of keeping the station in the line, as laid down, that it is necessary to examine the facts in the particular case. He rests the certainty of his contention on general principles, then long exploded, and further upon a sentence in Perry's charges, preferred in 1818, that "the commanding officer [Perry] issued, 1st, an order directing in what manner the line of battle should be formed … and enjoined upon the commanders to preserve their stations in the line" thus laid down.87 This is correct; but Cooper omits to give the words immediately following in the specification: "and in all cases to keep as near the commanding officer's vessel [the "Lawrence"] as possible."88 Cooper also omits that which next succeeds: "2d, An order of attack, in which the 'Lawrence' was designated to attack the enemy's new ship (afterwards ascertained to have been named the 'Detroit'), and the 'Niagara' designated to attack the 'Queen Charlotte,' which orders were then communicated to all the commanders, including the said Captain Elliott, who for that purpose … were by signal called together by the said commanding officer … and expressly instructed that 'if, in the expected engagement, they laid their vessels close alongside of those of the enemy, they could not be out of the way.'"89 An officer, if at once gallant and intelligent, finding himself behind a dull sailing vessel, as Cooper tells us the "Caledonia" was, could hardly desire clearer authority than the above to imitate his commanding officer when he made sail to close the enemy:—"Keep close to him," and follow up the ship which "the 'Niagara' was designated to attack."

Charges preferred are not technical legal proof, but, if duly scrutinized, they are statements equivalent in value to many that history rightly accepts; and, at all events, that which Cooper quotes is not duly scrutinized if that which he does not quote is omitted. He does indeed express a gloss upon them, in the words: "Though the 'Niagara' was ordered to direct her fire at the 'Queen Charlotte,' it could only be done from her station astern of the 'Caledonia,' … without violating the primary order to preserve the line."90 This does not correctly construe the natural meaning of Perry's full instructions. It is clear that, while he laid down a primary formation, "a line of battle," he also most properly qualified it by a contingent instruction, an "order of attack," designed to meet the emergency likely to occur in every fleet engagement, and which occurred here, when a slavish adherence to the line of battle would prevent intelligent support to the main effort. If he knew naval history, as his quotation from Nelson indicates, he also knew how many a battle had been discreditably lost by "keeping the line."