полная версия

полная версияSea Power in its Relations to the War of 1812. Volume 2

The results from the conditions above analyzed are reflected in the returns of commerce, in the movements of American coasters, and in the consequent dispositions of the enemy. In the Treasury year ending September 30, 1813, the value of the total exports from the Eastern states was $3,049,022; from the Middle section, $17,513,930; from the South, $7,293,043. Virginia is here reckoned with the Middle, because her exports found their way out by the Chesapeake; and this appreciation is commercial and military in character, not political or social. While this was the state of foreign trade under war conditions, the effect of local circumstances upon coasting is also to be noticed. The Middle section, characterized by the great estuaries, and by the description of its products,—grain primarily, and secondly tobacco,—was relatively self-sufficing and compact. Its growth of food, as has been seen, was far in excess of its wants, and the distance by land between the extreme centres of distribution, from tide-water to tide-water, was comparatively short. From New York to Baltimore by road is but four fifths as far as from New York to Boston; and at New York and Baltimore, as at Boston, water communication was again reached for the great lines of distribution from either centre. In fact, traffic from New York southward needed to go no farther than Elk River, forty miles short of Baltimore, to be in touch with the whole Chesapeake system. Philadelphia lies half-way between New York and Baltimore, approximately a hundred miles from each.

The extremes of the Middle section of the country were thus comparatively independent of coastwise traffic for mutual intercourse, and the character of their coasts co-operated to reduce the disposition to employ coasters in war. From the Chesapeake to Sandy Hook the shore-line sweeps out to sea, is safely approachable by hostile navigators, and has for refuge no harbors of consequence, except the Delaware. The local needs of the little communities along the beaches might foster a creeping stream of very small craft, for local supply; but as a highway, for intercourse on a large scale, the sea here was too exposed for use, when taken in connection with the facility for transport by land, which was not only short but with comparatively good roads.

In war, as in other troublous times, prices are subject to complicated causes of fluctuation, not always separable. Two great staples, flour and sugar, however, may be taken to indicate with some certainty the effects of impeded water transport. From a table of prices current, of August, 1813, it appears that at Baltimore, in the centre of the wheat export, flour was $6.00 per barrel; in Philadelphia, $7.50; in New York, $8.50; in Boston, $11.87. At Richmond, equally well placed with Baltimore as regarded supplies, but with inferior communications for disposing of its surplus, the price was $4.00. Removing from the grain centre in the other direction, flour at Charleston is reported at $8.00—about the same as New York; at Wilmington, North Carolina, $10.25. Not impossibly, river transportation had in these last some cheapening effect, not readily ascertainable now. In sugar, the scale is seen to ascend in an inverse direction. At Boston, unblockaded, it is quoted at $18.75 the hundredweight, itself not a low rate; at New York, blockaded, $21.50; at Philadelphia, with a longer journey, $22.50; at Baltimore, $26.50; at Savannah, $20. In the last named place, nearness to the Florida line, with the inland navigation, favored smuggling and safe transportation. The price at New Orleans, a sugar-producing district, $9.00, affords a standard by which to measure the cost of carriage at that time. Flour in the same city, on February 1, 1813, was $25 the barrel.

In both articles the jump between Boston and New York suggests forcibly the harassment of the coasting trade. It manifests either diminution of supply, or the effect of more expensive conveyance by land; possibly both. The case of the southern seaboard cities was similar to that of Boston; for it will not be overlooked that, as the more important food products came from the middle of the country, they would be equally available for each extreme. The South was the more remote, but this was compensated in some degree by better internal water communications; and its demand also was less, for the white population was smaller and less wealthy than that of New England. The local product, rice, also went far to supply deficiencies in other grains. In the matter of manufactured goods, however, the disadvantage of the South was greater. These had to find their way there from the farther extreme of the land; for the development of manufactures had been much the most marked in the east. It has before been quoted that some wagons loaded with dry goods were forty-six days in accomplishing the journey from Philadelphia to Georgetown, South Carolina, in May of this year. Some relief in these articles reached the South by smuggling across the Florida line, and the Spanish waters opposite St. Mary's were at this time thronged with merchant shipping to an unprecedented extent; for although smuggling was continual, in peace as in war, across a river frontier of a hundred miles, the stringent demand consequent upon the interruption of coastwise traffic provoked an increased supply. "The trade to Amelia,"—the northernmost of the Spanish sea-islands,—reported the United States naval officer at St. Mary's towards the end of the war, "is immense. Upwards of fifty square-rigged vessels are now in that port under Swedish, Russian, and Spanish colors, two thirds of which are considered British property."185 It was the old story of the Continental and License systems of the Napoleonic struggle, re-enacted in America; and, as always, the inhabitants on both sides the line co-operated heartily in beating the law.

The two great food staples chosen sufficiently indicate general conditions as regards communications from centre to centre. Upon this supervened the more extensive and intricate problem of distribution from the centres. This more especially imparted to the Eastern and Southern coasts the particular characteristics of coasting trade and coast warfare, in which they differ from the Middle states. These form the burden of the letters from the naval captains commanding the stations at Charleston, Savannah, and Portsmouth, New Hampshire; nor is it without significance that Bainbridge at Boston, not a way port, but a centre, displayed noticeably less anxiety than the others about this question, which less touched his own command. Captain Hull, now commanding the Portsmouth Yard, writes, June 14, 1813, that light cruisers like the "Siren," lately arrived at Boston, and the "Enterprise," then with him, can be very useful by driving away the enemy's small vessels and privateers which have been molesting the coasting trade. He purposes to order them eastward, along the Maine coast, to collect coasters in convoy and protect their long-shore voyages, after the British fashion on the high seas. "The coasting trade here," he adds, "is immense. Not less than fifty sail last night anchored in this harbor, bound to Boston and other points south. The 'Nautilus' [a captured United States brig] has been seen from this harbor every week for some time past, and several other enemy's vessels are on the coast every few days." An American privateer has just come in, bringing with her as a prize one of her own class, called the "Liverpool Packet," which "within six months has taken from us property to an immense amount."186

Ten days later Hull's prospects have darkened. There has appeared off Portsmouth a blockading division; a frigate, a sloop, and two brigs. "When our two vessels were first ordered to this station, I believed they would be very useful in protecting the coasting trade; but the enemy's cruisers are now so much stronger that we can hardly promise security to the trade, if we undertake to convoy it." On the contrary, the brigs themselves would be greatly hazarded, and resistance to attack, if supported by the neighborhood, may entail destruction upon ports where they have taken refuge; a thought possibly suggested by Cockburn's action at Havre de Grace and Frenchtown. He therefore now proposes that they should run the blockade and cruise at sea. This course was eventually adopted; but for the moment the Secretary wrote that, while he perceived the propriety of Hull's remarks, "the call for protection on that coast has been very loud, and having sent those vessels for that special purpose, I do not now incline immediately to remove them."187 It was necessary to bend to a popular clamor, which in this case did not, as it very frequently does, make unreasonable demands and contravene all considerations of military wisdom. A month later Hull reports the blockade so strict that it is impossible to get out by day. The commander of the "Enterprise," Johnston Blakely, expresses astonishment that the enemy should employ so large a force to blockade so small a vessel.188 It was, however, no matter for surprise, but purely a question of business. The possibilities of injury by the "Enterprise" must be blasted at any cost, and Blakely himself a year later, in the "Wasp," was to illustrate forcibly what one smart ship can effect in the destruction of hostile commerce and hostile cruisers.

Blakely's letter was dated July 31. The "Enterprise" had not long to wait for her opportunity, but it did not fall to his lot to utilize it. Being promoted the following month, he was relieved in command by Lieutenant William Burrows. This officer had been absent in China, in mercantile employment, when the war broke out, and, returning, was captured at sea. Exchanged in June, 1813, he was ordered to the "Enterprise," in which he saw his only service in the war,—a brief month. She left Portsmouth September 1, on a coasting cruise, and on the morning of the 5th, being then off Monhegan Island, on the coast of Maine, sighted a vessel of war, which proved to be the British brig "Boxer," Commander Samuel Blyth.

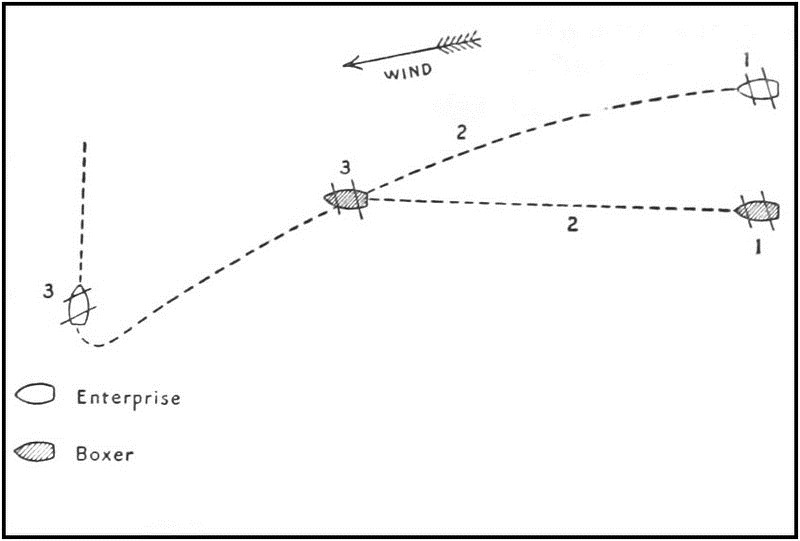

The antagonists in the approaching combat were nearly of equal force, the respective armaments being, "Enterprise," fourteen 18-pounder carronades, and two long 9-pounders, the "Boxer," twelve 18-pounder carronades and two long sixes. The action began side by side, at half pistol-shot, the "Enterprise" to the right and to windward (position 1). After fifteen minutes the latter ranged ahead (2). As she did so, one of her 9-pounders, which by the forethought of Captain Burrows had been shifted from its place in the bow to the stern,189 was used with effect to rake her opponent. She then rounded-to on the starboard tack, on the port-bow of the enemy,—ahead but well to the left (3),—in position to rake with her carronades; and, setting the foresail, sailed slowly across from left to right. In five minutes the "Boxer's" maintopmast and foretopsailyard fell. This left the "Enterprise" the mastery of the situation, which she continued to hold until ten minutes later, when the enemy's fire ceased. Her colors could not be hauled down, Blyth having nailed them to the mast. He himself had been killed at the first broadside, and almost at the same instant Burrows too fell, mortally wounded.

Diagram of the Enterprise vs. Boxer battle

The "Boxer" belonged to a class of vessel, the gun brigs, which Marryat through one of his characters styled "bathing machines," only not built, as the legitimate article, to go up, but to go down. Another,—the immortal Boatswain Chucks,—proclaimed that they would "certainly d—n their inventor to all eternity;" adding characteristically, that "their low common names, 'Pincher,' 'Thrasher,' 'Boxer,' 'Badger,' and all that sort, are quite good enough for them." In the United States service the "Enterprise," which had been altered from a schooner to a brig, was considered a singularly dull sailer. As determined by American measurements, taken four days after the action, the size of the two was the same within twenty tons; the "Boxer" a little the larger. The superiority of the "Enterprise" in broadside force, was eight guns to seven; or, stated in weight of projectiles, one hundred and thirty-five pounds to one hundred and fourteen. This disparity, though real, was in no sense decisive, and the execution done by each bore no comparison to the respective armaments. The hull of the "Boxer" was pierced on the starboard side by twelve 18-pound shot, nearly two for each of the "Enterprise's" carronades. The 9-pounder had done even better, scoring five hits. On her port side had entered six of 18 pounds, and four of 9 pounds. By the official report of an inspection, made upon her arrival in Portland, it appears that her upper works and sides forward were torn to pieces.190 In her mainmast alone were three 18-pound shot.191 As a set-off to this principal damage received, she had to show only one 18-pound shot in the hull of the "Enterprise," one in the foremast, and one in the mainmast.192

From these returns, the American loss in killed and wounded, twelve, must have been largely by grapeshot or musketry. The British had twenty-one men hurt. It has been said that this difference in loss is nearly proportionate to the difference in force. This is obviously inexact; for the "Enterprise" was superior in gun power by twelve per cent, while the "Boxer's" loss was greater by seventy-five per cent. Moreover, if the statement of crews be accurate, that the "Enterprise" had one hundred and twenty and the "Boxer" only sixty-six,193 it is clear that the latter had double the human target, and scored little more than half the hits. The contest, in brief, was first an artillery duel, side to side, followed by a raking position obtained by the American. It therefore reproduced in leading features, although on a minute scale, the affair between the "Chesapeake" and "Shannon"; and the exultation of the American populace at this rehabilitation of the credit of their navy, though exaggerated in impression, was in principle sound. The British Court Martial found that the defeat was "to be attributed to a superiority of the enemy's force, principally in the number of men, as well as to a greater degree of skill in the direction of her fire, and the destructive effects of her first broadside."194 This admission as to the enemy's gunnery is substantially identical with the claim made for that of the "Shannon,"—notably as to the first broadside. As to the greater numbers, one hundred and twenty is certainly almost twice sixty-six, and the circumstance should be weighed; but in an engagement confined to the guns, and between 18-pounder carronade batteries, it is of less consequence than at first glance appears. A cruiser of those days expected to be ready to fight with many men away in prizes. Had it come to boarding, or had the "Boxer's" gunnery been good, disabling her opponent's men, the numbers would have become of consideration. As it was, they told for something, but not for very much.

If national credit were at issue in every single-ship action, the balance of the "Chesapeake" and "Shannon," "Enterprise" and "Boxer," would incline rather to the American side; for the "Boxer" was not just out of port with new commander, officers, and crew, but had been in commission six months, had in that time crossed the ocean, and been employed along the coast. The credit and discredit in both cases is personal, not national. It was the sadder in Blyth's case because he was an officer of distinguished courage and activity, who had begun his fighting career at the age of eleven, when he was on board a heavily battered ship in Lord Howe's battle of June 1, 1794. At thirty, with little influence, and at a period when promotion had become comparatively sluggish, he had fairly fought his way to the modest preferment in which he died. Under the restricted opportunities of the United States Navy, Burrows had seen service, and his qualities received recognition, in the hostilities with Tripoli. The unusual circumstance of both captains falling, and so young,—Burrows was but twenty-eight,—imparted to this tiny combat an unusual pathos, which was somewhat heightened by the fact that Blyth himself had acted as pall-bearer when Lawrence, three months before, was buried with military honors at Halifax. In Portland, Maine, the two young commanders were borne to their graves together, in a common funeral, with all the observance possible in a small coast town; business being everywhere suspended, and the customary tokens of mourning displayed upon buildings and shipping.

After this engagement, as the season progressed, coastwise operations in this quarter became increasingly hazardous for both parties. On October 22, Hull wrote that neither the "Enterprise" nor the "Rattlesnake" could cruise much longer. The enemy still maintained his grip, in virtue of greater size and numbers. Ten days later comes the report of a convoy, with one of the brigs, driven into port by a frigate; that the enemy appear almost every day, and never without a force superior to that of both his brigs, which he fears to trust out overnight, lest they find themselves at morning under the guns of an opponent of weightier battery. The long nights and stormy seas of winter, however, soon afforded to coasters a more secure protection than friendly guns, and Hull's letters intermit until April 6, 1814, when he announces that the enemy has made his appearance in great force; he presumes for the summer. Besides the danger and interruption of the coasting trade, Hull was increasingly anxious as to the safety of Portsmouth itself. By a recent act of Congress four seventy-fours had been ordered to be built, and one of them was now in construction there under his supervision. Despite the navigational difficulties of entering the port, which none was more capable of appreciating than he, he regarded the defences as so inadequate that it would be perfectly possible to destroy her on the stocks. "There is nothing," he said, "to prevent a very small force from entering the harbor." At the same moment Decatur was similarly concerned for the squadron at New London, and we have seen the fears of Stewart for Norfolk. So marked was Hull's apprehension in this respect, that he sent the frigate "Congress" four miles up the river, where she remained to the end of the war; her crew being transferred to Lake Ontario. New York, the greater wealth of which increased both her danger and her capacity for self-protection, was looking to her own fortifications, as well as manning, provisioning, and paying the crews of the gunboats that patrolled her waters, on the side of the sea and of the Sound.

The exposure of the coasting trade from Boston Bay eastward was increased by the absence of interior coastwise channels, until the chain of islands about and beyond the Penobscot was reached. On the other hand, the character of the shore, bold, with off-lying rocks and many small harbors, conferred a distinct advantage upon those having local knowledge, as the coasting seamen had. On such a route the points of danger are capes and headlands, particularly if their projection is great, such as the promontory between Portsmouth and Boston, of which Cape Ann is a conspicuous landmark. There the coaster has to go farthest from his refuge, and the deep-sea cruiser can approach with least risk. In a proper scheme of coast defence batteries are mounted on such positions. This, it is needless to say, in view of the condition of the port fortifications, had not been done in the United States. Barring this, the whole situation of the coast, of trade, and of blockade, was one with which British naval officers had then been familiar for twenty years, through their employment upon the French and Spanish coasts, as well Mediterranean as Atlantic, and in many other parts of the world. To hover near the land, intercepting and fighting by day, manning boats and cutting out by night, harassing, driving on shore, destroying the sinews of war by breaking down communications, was to them simply an old experience to be applied under new and rather easier circumstances.

Of these operations frequent instances are given in contemporary journals and letters; but less account has been taken of the effects, as running through household and social economics, touching purse and comfort. These are traceable in commercial statistics. At the time they must have been severely felt, bringing the sense of the war vividly home to the community. The stringency of the British action is betrayed, however, by casual notices. The captain of a schooner burned by the British frigate "Nymphe" is told by her commander that he had orders to destroy every vessel large enough to carry two men. "A brisk business is now carrying on all along our coast between British cruisers and our coasting vessels, in ready money. Friday last, three masters went into Gloucester to procure money to carry to a British frigate to ransom their vessels. Thursday, a Marblehead schooner was ransomed by the "Nymphe" for $400. Saturday, she took off Cape Ann three coasters and six fishing boats, and the masters were sent on shore for money to ransom them at $200 each." There was room for the wail of a federalist paper: "Our coasts unnavigable to ourselves, though free to the enemy and the money-making neutral; our harbors blockaded; our shipping destroyed or rotting at the docks; silence and stillness in our cities; the grass growing upon the public wharves."195 In the district of Maine, "the long stagnation of foreign, and embarrassment of domestic trade, have extended the sad effects from the seaboard through the interior, where the scarcity of money is severely felt. There is not enough to pay the taxes."196

South of Chesapeake Bay the coast is not bold and rocky, like that north of Cape Cod, but in its low elevation and gradual soundings resembles rather those of New Jersey and Delaware. It has certain more pronounced features in the extensive navigable sounds and channels, which lie behind the islands and sandbars skirting the shores. The North Carolina system of internal water communications, Pamlico Sound and its extensions, stood by itself. To reach that to the southward, it was necessary to make a considerable sea run, round the far projecting Cape Fear, exposed to capture outside; but from Charleston to the St. Mary's River, which then formed the Florida boundary for a hundred miles of its length, the inside passages of South Carolina and Georgia were continuous, though in many places difficult, and in others open to attack from the sea. Between St. Mary's and Savannah, for example, there were seven inlets, and Captain Campbell, the naval officer in charge of that district, reported that three of these were practicable for frigates;197 but this statement, while literally accurate, conveys an exaggerated impression, for no sailing frigate would be likely to cross a difficult bar for a single offensive operation, merely to find herself confronted with conditions forbidding further movement.

The great menace to the inside traffic consisted in the facility with which cruisers outside could pass from entrance to entrance, contrasted with the intricacies within impeding similar action by the defence. If a bevy of unprotected coasters were discerned by an enemy's lookouts, the ship could run down abreast, send in her boats, capture or destroy, before the gunboats, if equidistant at the beginning, could overcome the obstacles due to rise and fall of tide, or narrowness of passage, and arrive to the rescue.198 A suggested remedy was to replace the gunboats by rowing barges, similar to, but more powerful than, those used by the enemy in his attacks. The insuperable trouble here proved to be that men fit for such work, fit to contend with the seamen of the enemy, were unwilling to abandon the sea, with its hopes of prize money, or to submit to the exposure and discomfort of the life. "The crews of the gunboats," wrote Captain Campbell, "consist of all nations except Turks, Greeks, and Jews." On one occasion the ship's company of an American privateer, which had been destroyed after a desperate and celebrated resistance to attack by British armed boats, arrived at St. Mary's. Of one hundred and nineteen American seamen, only four could be prevailed upon to enter the district naval force.199 This was partly due to the embarrassment of the national finances. "The want of funds to pay off discharged men," wrote the naval captain at Charleston, "has given such a character to the navy as to stop recruiting."200 "Men could be had," reported his colleague at St. Mary's, now transferred to Savannah, "were it not for the Treasury notes, which cannot be passed at less than five per cent discount. Men will not ship without cash. There are upwards of a hundred seamen in port, but they refuse to enter, even though we offer to ship for a month only."201