Полная версия

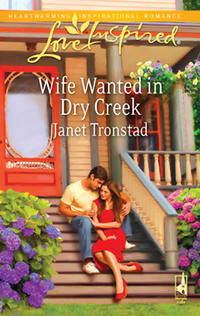

Shepherds Abiding in Dry Creek

Shepherds Abiding in Dry Creek

Janet Tronstad

Published by Steeple Hill Books™

MILLS & BOON

Before you start reading, why not sign up?

Thank you for downloading this Mills & Boon book. If you want to hear about exclusive discounts, special offers and competitions, sign up to our email newsletter today!

SIGN ME UP!

Or simply visit

signup.millsandboon.co.uk

Mills & Boon emails are completely free to receive and you can unsubscribe at any time via the link in any email we send you.

Dedicated to my grandfather, Harold Norris.

I remember him for his small kindnesses

and his big heart. He was a good man.

Contents

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Epilogue

Chapter One

“I am the good shepherd; the good shepherd giveth his life for the sheep.”

John 10:11

Marla Gossett sat in her bare apartment on the one wooden chair she had left to her name. The apartment building faced a busy street in south central Los Angeles, with the constant hum of cars going by. Marla didn’t even hear the noise any longer. She’d sold her sofa yesterday and the kids’ beds the day before that. She wished she could at least take the beds with them, but they wouldn’t fit in the car when they moved. Besides, they all had sleeping bags.

Right now she was in the middle of selling her lamp to the African-American woman who had moved in down the hall a week ago.

Marla had given up on selling the chair she was sitting on. No one was willing to buy it with “XIX” carved into the arm. Not that she blamed them. She felt uneasy just sitting on the thing herself. She had put a notice in the hallway a week ago and several people had asked about the chair until they saw the numbers.

“You’ll have a new life away from here,” her African-American neighbor—Susan was her name—said softly. Susan was looking at these numbers on the chair. “Your son?”

Marla nodded. She wasn’t proud that her eleven-year-old son, Sammy, had carved the sign of the 19th Street gang into her furniture. She told herself it was only natural for young boys to be impressed with the tough guys that ruled their neighborhood. The 19th Street gang was the largest Hispanic gang in Los Angeles. She knew her son was just an onlooker at this point. Other people didn’t know that, though, and they were scared to buy the chair even if it was solid oak and had been the finest piece of furniture she owned.

The chair had been a wedding gift, and there was a matching wooden cross that came to hang behind it.

Susan looked up from the chair. “Well, I guess they have gangs everywhere. Where are you going, anyway?”

“A place called Dry Creek, Montana. My husband had an uncle who left us a house there before he died.”

“Did your husband get a chance to show it to you?”

Marla shook her head. She had already shared her vital statistics, so the woman knew her husband had died from lung cancer last year.

“Well, at least he left you with something,” Susan said in a tone that implied she didn’t expect much from men. “Of course, it would have been better if he’d gotten you some life insurance.”

“We always thought there was plenty of time.”

The woman nodded, and Marla wondered how it was that death had become so commonplace. Some days she wanted to scream at the injustice of it, but more often it just weighed her down with its ordinariness.

She had been a widow for over a year, and it still felt like yesterday. She’d married Jorge when she was nineteen, and it hadn’t taken long for the blaze of romance between them to settle into a steady flame of affection. At least, she had assumed the flame was steady. That was the way it had been on her side.

The cancer came hard and swiftly. It wasn’t until Jorge was gone that she had had time to think about her marriage. Near the end, when he could barely speak, Jorge confessed he’d been unfaithful several times and pleaded with her to forgive him. He said he didn’t want to die with those sins on his conscience.

After his diagnosis, Jorge had started praying often and had asked her to move their wooden cross into the bedroom. It seemed to comfort him, and Marla was glad for that. She believed her husband did repent his sins. So what could she do? There was no time to work through her feelings. She forgave him because she had to, and then he lost consciousness, dying later that same night.

When he was gone, all Marla could think about was their marriage. She kept wondering if something was lacking in her, and if that was why Jorge had not loved her enough to be faithful or to even talk to her about his problems. Maybe she didn’t inspire love the way other women did.

Even when he’d proposed, Jorge had not made any grand gestures of love toward her. Marla had not thought anything was wrong with that, though; she thought it was just the way he was. Marriage wasn’t all about roses and valentines. She’d accepted that. But had she missed some clue? Or were there many little clues she had ignored? Was a woman supposed to keep a tally of things that would tell her if her husband still loved her? How could she not even have known he was unfaithful?

As her feelings for Jorge changed, Marla wondered if she’d ever really known her husband. Still, especially in the past few weeks, she’d wished he were still alive so they could share the problems about Sammy. Jorge might have been unfaithful to her, but he had loved Sammy. What would Sammy do without his dad?

Worrying about Sammy had made her take the cross out of the box, where she’d put it after Jorge died, and hang it on the wall again. Sometimes she’d look at it, searching for the solace her husband had found in it. She wished she could find an answer for Sammy there. The cross didn’t speak to her the way it had to Jorge.

“Did you say Montana?” Susan was frowning for the first time.

Marla nodded. She wondered why the mention of Montana was disturbing her neighbor more than their earlier discussion about death had.

“They don’t have much color there.”

“You mean trees?”

Susan pursed her lips as she turned to study Marla. “No, I mean people.”

Marla had combed her hair this morning, as she did every morning. It was freshly washed and fell smoothly to her shoulders. At thirty-five, she knew she was no great beauty, but her skin was light olive, and she’d been told her eyes were nice. Her brown hair didn’t sparkle with highlights, but she looked all right. She wondered why Susan was looking at her with such an intense expression.

Her neighbor finally nodded. “You’ll do fine, though. I’d guess you’re—what—half Hispanic?”

“On my mother’s side.”

Susan kept nodding. “And your son and daughter. I’ve seen them. They could be white.”

Jorge had been half-and-half—Hispanic-Anglo—as well. That had been one of the things they had in common. “They pride themselves on being Hispanic, especially my son.”

Susan grunted. “That’s just gang talk. He’ll get over it quick enough when he’s away from here.”

“I’m not sure I want him to get over it,” Marla said stiffly. “He should be proud of his roots.”

So much had been taken from them. She had to draw the line somewhere.

“Take my advice and blend in,” Susan said as she picked up the lamp. “You’ve got a better chance of getting a new husband that way. Especially in a place like that.”

“But—” Marla protested. She wasn’t sure if she was protesting hiding her roots to find a husband or looking for a husband in the first place. She supposed she would have to marry if she wanted a new father for her children. But she wasn’t ready for that yet. What if a second marriage proved only how lacking she was as a woman? There was no reason to believe she’d do any better the second time around than she had the first.

“Trust me. No one wants to have a Hispanic gang member in their neighborhood, no matter where they live. If they don’t know you’re Hispanic, there’s no reason for them to make the 19th Street connection.”

“But Sammy’s not in the gang. Not really.”

Susan held up her hands. “I’m just saying these people will be nervous. There was an article in Time magazine last month—or was it Newsweek? Anyway, it was about gangs sending scouts out to small towns to see about setting up safe houses there. They want to have a place to send their guys so they can hide out from the police if things get bad. I wouldn’t blame a small town for being careful.”

“Well, of course they should be careful, but…”

Susan looked at the carving on the armchair again and then just shrugged. “I had a cousin drive through Montana a few years ago. If I remember right, he said the population is only about two percent Hispanic for the whole state. How big is this Dry Creek place you’re moving to?”

“Two hundred people.”

Susan nodded as she pulled the agreed-upon five-dollar bill from her pocket. “Then you and your kids will probably be the token two percent.”

Marla frowned as she stood up. She was ready for the woman to leave. “We’re probably not that far from a large city. Maybe Billings. There’ll be all kinds of people there.”

Susan snorted as she finished handing the bill to Marla. “All I can say is that you’ll want to take your chili peppers with you. I doubt you’ll find more than salt and pepper around there. It’s beef and potato country in more ways than one.”

Marla slipped the bill into her pocket. “We don’t have a choice about going.”

She didn’t want to tell her neighbor that the police had come to her door a little over a week ago and warned her that Sammy was on the verge of becoming a real member of that 19th Street gang. She figured they were exaggerating, but she couldn’t take a chance. She had given notice at her cashier job and started to make plans. She had to get Sammy out of here, even if it made every soul in Dry Creek nervous. At least she would own the house where they would live, so no one could force them to leave. Sammy and her four-year-old daughter, Becky, would be safe. That was all Marla cared about for now.

The neighbor took one more look at the scarred chair. “I guess we all do what we need to do in life. It’s too bad. It was a nice chair.”

Marla nodded.

“I wish you well,” Susan said as she started walking to the door. “And, who knows, it might not be so bad. My cousin said they have rodeos in the summer and snow for Christmas. He liked the state.”

Marla mumbled goodbye as the neighbor left her apartment. She’d been anxious about the move before talking to Susan. Now she could barely face the thought of going to Dry Creek. But looking down at the arm of that wooden chair, she knew she had to go. She’d lost her husband; she refused to lose her son, too.

She wouldn’t hide their ethnic roots from the people in Montana, but she saw no reason to advertise them, either. And, of course, she’d keep quiet about Sammy’s brush with gang life, especially because it would all be in the past once she got him out of Los Angeles. She was sure of that. She had to be. Dry Creek was her last hope.

Chapter Two

A few weeks later

Les Wilkerson knew something was wrong when his phone rang at six o’clock in the morning. He’d just come in from doing the chores in the barn and was starting to pull his boots off so he wouldn’t get the kitchen floor dirty while he cooked his breakfast. It was the timing of the call that had him worried. He’d given the people of Dry Creek permission to call him on sheriff business after six and it sounded as if someone had been waiting until that exact moment to make a call.

Les finished pulling off his boots and walked in his stocking feet to the phone. By that time, enough unanswered rings had gone by to discourage the most persistent telemarketers.

“I think we’ve had a theft,” Linda, the young woman who owned the Dry Creek café, said almost before Les got the phone to his ear. She was out of breath. “Or maybe it’s one of those ecology protests. You know, the green people.”

“Someone’s protesting in Dry Creek?”

Dry Creek had more than its share of independent-minded people. Still, Les had never known any of them to do something like climb an endangered tree and refuse to come down, especially not in the dead of winter when there was fresh snow on the ground.

“I don’t know. It’s either that or a theft. You know the Nativity set the church women’s group just got?”

“Of course.”

Everyone knew the Nativity set. The women had collected soup-can labels for months and traded them like green stamps to get a life-size plastic Nativity set that lit up at night. Les was sure he’d eaten more tomato soup recently than he had in his entire life.

“Well, the shepherd’s not there. We don’t know what happened to him, but we can’t see him. Charley says that Elmer has been upset about all of the electricity the church is using to light everything up. He says someone either took the shepherd or Elmer unplugged it to protest the whole thing.”

Les had known there would be problems with people eating all that soup. It made old ranchers like Elmer and Charley irritable. It was probably bad for their blood pressure, too.

“Unplugging something is not much of a protest. It could even be a mistake.” Now, that was a whole lot more likely than some high-minded protest, Les thought, and then he remembered promising the regular sheriff that he would be patient with everyone. “But I’ll talk to Elmer, anyway, and explain how important the Nativity set is and what a sacrifice everyone made so we could have it.”

Les was sure Elmer would agree about the sacrifice part. He’d said he was eating so much soup he might as well have false teeth.

There were some muffled voices in the background that Les couldn’t make out over the phone.

“That’s Elmer now. He just came in and he claims he didn’t unplug anything. He says if we can’t see the shepherd, it’s because it’s not there and Charley’s right that somebody stole it.”

“The light could be burned out.” Patience went only so far, Les thought. He wasn’t going to go chasing phantom criminals just because someone thought something was stolen. There hadn’t been an attempted theft in Dry Creek since that woman had broken into the café two years ago. And she had not even taken anything. After all that time, it wasn’t likely someone would suddenly decide to steal a plastic shepherd.

“Maybe it is a defective light,” Linda agreed. “But I’m going to tell Charley and Elmer not to go over and check. It’s still pitch-black outside. Charley’s been looking out the café window for a good fifteen minutes, and it’s still too dark to see if the shepherd is there. And if it’s not there, then it could be a crime scene and we’d need the professionals.” Linda’s voice dipped so low that only Les could hear it. “Besides, the two of them could fall and break half their bones going over there in the dark. You know how that patch of street in front of the church is always so slippery when we’ve had snow. So I’ll tell them you’re going to handle it. Okay?”

“Sounds good,” Les said. He’d rather safeguard old bones than chase after imaginary thieves any day. “I’ll be right there.”

Les usually made a morning trip into town, anyway, before he drove a load of hay out to the cattle he was wintering in the far pasture. The little town of Dry Creek wasn’t much—a hardware store, a church, a café and a dozen or so houses—but the regular sheriff guarded the place as if it was Fort Knox, and Les, who was the town’s only volunteer reserve deputy, had promised he’d do the same in the sheriff’s absence.

Just thinking of the sheriff made Les shake his head. Who would figure that a man as shy as Sheriff Carl Wall would ever have a wedding, let alone a belated honeymoon to celebrate with a trip to Maui?

It was all Les could do not to be jealous. After all, he was as good-looking as Carl, or at least no worse looking. Les even owned his own ranch, as sweet a piece of earth as God ever created, and it was all paid for. Not every man could say that. He should be content. But for the past week every time he thought of Carl and that honeymoon trip of his, Les started to frown.

If Sheriff Carl Wall could get married, Les figured he should be married, too. He was almost forty years old and, although he enjoyed being single, a man could spend only so much time in his own company before, well, he got a little tired of it. Besides, it would be nice to have a woman’s touch around the place. Les knew he could hire someone to do most of the cooking and cleaning. But it wouldn’t be the same. A woman just naturally made a home around her, like a mother bird making her nest. A man’s house wasn’t a home without some nesting going on.

Of course, Les told himself as he pulled his pickup to a stop beside the café, the sheriff had gone a little overboard with it all. He had completely lost his dignity, the way he had moped around until Barbara Strong agreed to marry him. Les would never do that. He had already seen too many tortured love scenes in his life; he had no desire to play the lead in one himself.

His parents were the reason for his reluctance to marry. They had had many very public partings and equally dramatic reconciliations. Les never knew whether they were breaking up or getting back together. The two of them should have sold tickets to their lives. They certainly could have used some help with finances, given the salary his father earned in that shoe store in Miles City. Half their arguments were about money. The other half were about who didn’t love whom enough.

His parents were both dead now, but Les had never understood how they could be the way they were. They were so very public about how they felt about everything, from love to taxes. As a child Les had vowed to stay away from that kind of circus. It was embarrassing. Growing up, he never even made a fuss over his dog, because he didn’t want anyone to think he was becoming like his parents.

No, Les thought as he stepped up on the café porch, if he was going to get married there would be no emotional public scenes. It would all be a nice sensible arrangement with a nice quiet woman. There was no reason for two people to make fools of themselves just because they wanted to get married, anyway.

“Oh, good. You’re here.” Linda’s voice greeted Les as he opened the door.

The café floor was covered with alternating black and white squares of linoleum. Formica-topped tables sat in the middle of the large room, and a counter ran along one of its sides. The air smelled of freshly made coffee and fried bacon.

Elmer and Charley were sitting at the table closest to the door and they both looked up from their plates as Les stepped inside. They had flushed faces and excitement in their eyes.

“They already went over to the church,” Linda whispered as she closed the door behind Les. “They snuck out when I was in the kitchen making their pancakes.”

Les could tell the two men were primed to tell him something. It hadn’t stopped them from eating their pancakes and bacon, though. All that was left on their plates was syrup. Les walked closer to them. Fortunately, no one had ever suggested people should have soup for breakfast, so that meal had always been safe.

“It’s a crime,” Elmer announced from where he sat. He had his elbows on the table and his cap sitting on the straight-backed chair next to him.

“We thought maybe you were right about the light just burning out,” Charley explained as he pushed his chair back a little from the table. “We didn’t want to bother anyone if that was all that happened, so we went over to take a look.”

“Looks like a kidnapping to me,” Elmer declared confidently, then paused to glance up at Les. “Is it a kidnapping if the kidnapee in question is plastic?”

“No,” Les said. He didn’t need to call upon his reserve deputy sheriff training to answer that question. “It’s not even a theft if someone just moved the figure. That’s probably what happened. Maybe the pastor decided the Nativity had too many figures on the left side and put the shepherd inside the church until he could set it up on the other side.”

Les reminded himself to get these two men a new checkerboard for Christmas. A dog had chewed up their old cardboard one a month ago, and now, instead of sitting in the hardware store playing checkers, they just sat, either in the hardware store or in the café, and talked. Too much talking was giving them some pretty wild ideas. He couldn’t think of one good reason anyone would steal a plastic shepherd, not even one that lit up like a big neon sign at night.

Charley shook his head. “Naw, that can’t be it. All of the wise men are on the other side. The pastor wouldn’t think there are too many figures on the left. Not even with the angel on the left—and she’s a good-sized angel.”

“Besides, we know it’s not the pastor moving things around, because we found this,” Elmer said as he thrust a piece of paper toward Les. “Wait until you see this.”

Les’s heart sank when he saw the sheet of paper. He had a feeling he knew what kind of note it was. It had a ragged edge where it had been torn from what was probably a school tablet. There must be a dozen school tablets in Dry Creek. The note was written in pencil, and he didn’t even want to think about how many pencils there were around. Anyone could have written a note like this.

Les bent to read it.

Dear Church People,

I took your dumb shepherd.

If you want to see him again, leave a Suzy bake set on the back steps of your church. It needs to be the deluxe kind—the one with the cupcakes on the box.

P.S. Don’t call the cops.

P.P.S. The angel wire is loose. She’s going to fall if somebody doesn’t do something.

XIX

Well, there was one good thing, Les told himself as he looked up from the paper. There weren’t that many people in Dry Creek who would want a Suzy bake set. That narrowed down the field of suspects considerably. He assumed the XIX at the bottom was some reference to a biblical text on charity. Or maybe a promise to heap burning coals on someone who didn’t do what they were told.

“So it looks like the shepherd is really gone,” Les said, more to give himself time to think than because there seemed to be any question about that fact, at least.

Elmer nodded. “The angel is just standing there with her wings unfurled looking a little lost now that she’s proclaiming all that good news to a couple of sheep. You don’t see anything standing where that shepherd should be.”

The door to the café opened briskly and an older woman stepped inside. She had a wool jacket wrapped around her shoulders and boots on her feet. Les thought she still had to be cold, though, in that gingham dress she was wearing. Cotton didn’t do much to protect a person from a Montana winter chill.

“Mrs. Hargrove, you shouldn’t be walking around these streets. They’re slippery,” Les said to the woman. The older people in Dry Creek just didn’t seem to realize how hazardous it was outside after it snowed. And they’d lived here their whole lives, so if anyone should know, they should.

“Charley told me some little girl was in trouble.” Mrs. Hargrove glared at Les as she unwound the scarf from around her neck and set down the bag she was carrying. “Something about kidnapping and theft. I hope you’re not planning to arrest a little girl.”