полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

In the character of its flight it is said to strongly resemble the Brown Thrasher (H. rufus) of the Eastern States. Their harsh, scolding notes, when their nest is approached, their motions and attitudes, are all very similar to those of H. rufus under like circumstances. Colonel McCall ranks the song of this species as far superior to that of any other Thrush. Without possessing the powerful voice or imitative faculties of the Mocking-Bird, its notes are described as having a liquid mellowness of tone, with a clearness of expression and volubility of utterance that cannot be surpassed.

A nest of this bird found by Dr. Heermann was composed of coarse twigs, and lined with slender roots, and not very carefully constructed. Mr. Hepburn writes that a nest found by him was in a thick bush about five feet from the ground. It was a very untidy affair, a mere platform of sticks, almost as carelessly put together as that of a pigeon, in which, though not in the centre, was a shallow depression about 4 inches in diameter, lined with fine roots and grass. It contained two eggs with a blue ground thickly covered with soot-colored spots confluent at the larger end, and in coloring not unlike those of the Turdus ustulatus. The eggs measured 1.19 inches by .81 of an inch. Dr. Cooper gives their measurement as 1.10 of an inch by .85. Two eggs belonging to the Smithsonian Institution (2,040, a and b) measure, one 1.19 by .81, the other 1.14 by .93. The former has a bluish-green ground sparsely spotted with olive-brown markings; the other has a ground of a light yellowish-green, with numerous spots of a russet brown.

The general character of their nest is, as described, a coarse, rudely constructed platform of sticks and coarse grass and mosses, with but a very slight depression. Occasionally, however, nests of this bird are more carefully and elaborately made. One (13,072) obtained near Monterey, by Dr. Canfield, has a diameter of 6 inches, a height of 3, with an oblong-oval cavity 2 inches in depth. Its outside was an interweaving of leaves, stems, and mosses, and its lining fine long fibrous roots.

These birds are chiefly found frequenting the dense chaparral that lines the hillsides of California valleys, forming thickets, composed of an almost impenetrable growth of thorny shrubs, and affording an inviting shelter. In such places they reside throughout the year, feeding upon insects, for the procuring of which their long curved bills are admirably adapted, as also upon the berries which generally abound in these places. Their nests usually contain three eggs. Dr. Cooper states that their loud and varied song is frequently intermingled with imitations of other birds, though the general impression appears to be that they are not imitative, and do not deserve to be called, as they often are, a mocking-bird.

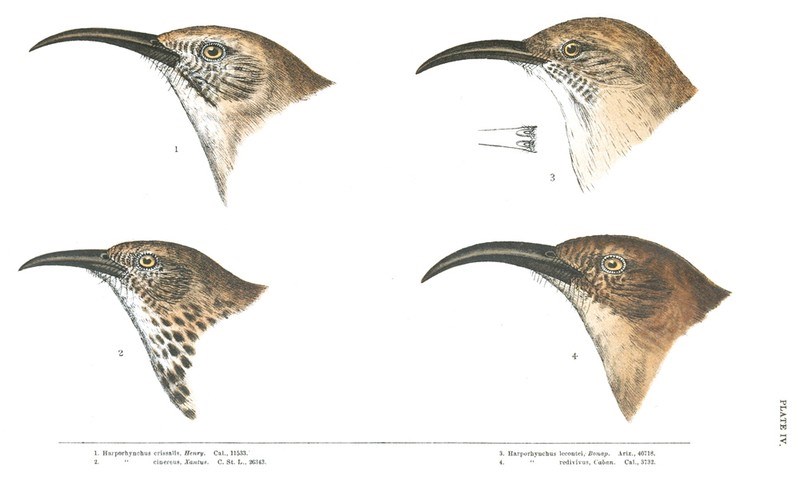

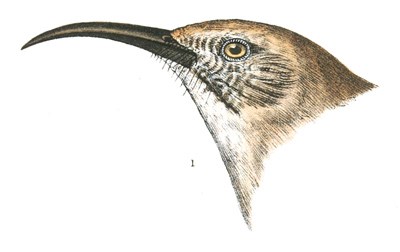

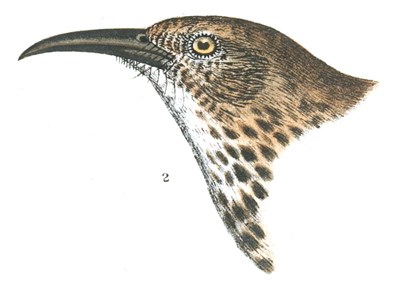

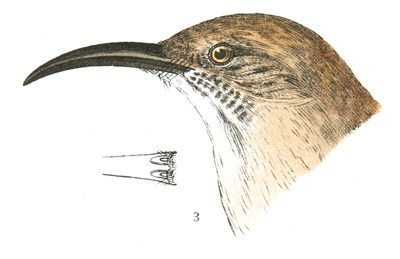

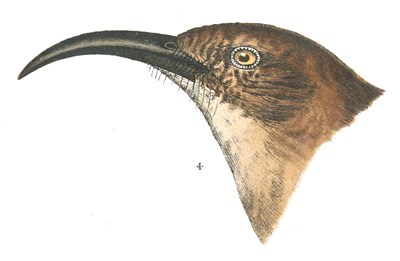

PLATE IV.

1. Harporhynchus crissalis, Henry. Cal., 11533.

2. Harporhynchus cinereus, Xantus. C. St. L., 26343.

3. Harporhynchus lecontei, Bonap. Ariz., 40718.

4. Harporhynchus redivivus, Caban. Cal., 3732.

Harporhynchus crissalis, HenryRED-VENTED THRASHER

Harporhynchus crissalis, Henry, Pr. A. N. Sc. May, 1858.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 350, pl. lxxxii; Review, 47.—Cooper, Birds Cal. 1, 18.

Sp. Char. Second quill about as long as the secondaries. Bill much curved; longer than the head. Above olive-brown, with a faint shade of gray; beneath nearly uniform brownish-gray, much paler than the back, passing insensibly into white on the chin; but the under tail-coverts dark brownish-rufous, and abruptly defined. There is a black maxillary stripe cutting off a white one above it. There do not appear to be any other stripes about the head. There are no bands on the wings, and the tips and outer edges of the tail-feathers are very inconspicuously lighter than the remaining portion. Length, 11 inches; wing, 4.00; tail, 5.80; tarsus, 1.25.

Hab. Region of the Gila River, to Rocky Mountains; Southern Utah (St. George, Dr. Palmer).

A second specimen (11,533) of this rare species is larger than the type, but otherwise agrees with it. Its dimensions are as follows:—

Length before skinning, 12.50; of skin, 12.50; wing, 3.90; tail, 6.50; its graduation, 1.45; first quill, 1.50; second, .41; bill from forehead (chord of curve), 1.65, from gape, 1.75, from nostril, 1.30; curve of culmen, 1.62; height of bill at nostril, .22; tarsus, 1.30; middle toe and claw, 1.12.

The bill of this species, though not quite so long as in redivivus, when most developed, is almost as much curved, and much more slender,—the depth at nostrils being but .22 instead of .26. The size of this specimen is equal to the largest of redivivus (3,932); the tail absolutely longer. The feet are, however, considerably smaller, the claws especially so; the tarsus measures but 1.30, instead of 1.52; the middle claw .29, instead of .36. With these differences in form, however, it would be impossible to separate the two generically.

A third specimen (No. 60,958 ♀, St. George, Utah, June 9, 1870), with nest and eggs, has recently been obtained by Dr. Palmer. This specimen, being a female, is considerably smaller than the type, measuring only: wing, 3.90; tail, 6.00; bill, from nostril, 1.15. The plumage is in the burnt summer condition, and has a peculiar reddish cast.

Habits. Of this rare Thrush little is known. So far as observed, its habits appear to be nearly identical with those of the Californian species (H. redivivus). It is found associated in the same localities with H. lecontei, which also it appears to very closely resemble in all respects, so far as observed. The first specimen was obtained by Dr. T. C. Henry, near Mimbres, and described by him in May, 1858, in the Proceedings of the Philadelphia Academy of Sciences. A second specimen was obtained by H. B. Möllhausen, at Fort Yuma, in 1863. Dr. Coues did not observe it at Fort Whipple, but thinks its range identical with that of H. lecontei.

Dr. Cooper found this species quite common at Fort Mojave, but so very shy that he only succeeded in shooting one, after much watching for it. Their song, general habits, and nest he speaks of as being in every way similar to those of H. redivivus.

The eggs remained unknown until Dr. E. Palmer had the good fortune to find them at St. George, Southern Utah, June 8, 1870. The nest was an oblong flat structure, containing only a very slight depression. It was very rudely constructed externally of coarse sticks quite loosely put together; the inner nest is made of finer materials of the same. The base of this nest was 12 inches long, and 7 in breadth; the inner nest is circular, with a diameter of 4½ inches.

The eggs are of an oblong-oval shape, one end being a little less obtuse than the other. In length they vary from 1.15 to 1.12 inches, and in breadth from .84 to .82 of an inch. They are of a uniform blue color, similar to the eggs of the common Robin (Turdus migratorius), only a little paler or of a lighter tint. In the total absence of markings they differ remarkably from those of all other species of the genus.

Genus MIMUS, BoieMimus, Boie, Isis, Oct. 1826, 972. (Type Turdus polyglottus, Linn.)

Orpheus, Swainson, Zoöl. Jour. III, 1827, 167. (Same type.)

Mimus polyglottus.

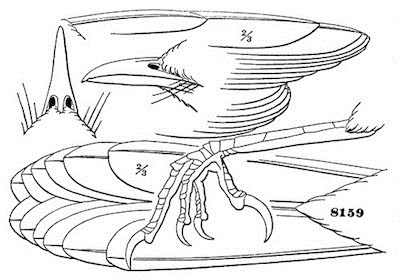

8159

Gen. Char. Bill not much more than half the length of the head; gently decurved from the base, notched at tip; commissure curved. Gonys straight, or slightly concave. Rictal bristles quite well developed. Wings rather shorter than the tail. First primary about equal to, or rather more than, half the second; third, fourth, and fifth quills nearly equal, sixth scarcely shorter. Tail considerably graduated; the feathers stiff, rather narrow, especially the outer webs, lateral feathers about three quarters of an inch the shorter in the type. Tarsi longer than middle toe and claw by rather less than an additional claw; tarsi conspicuously and strongly scutellate; broad plates seven.

Of this genus there are many species in America, although but one occurs within the limits of the United States.

The single North American species M. polyglottus is ashy brown above, white beneath; wings and tail black, the former much varied with white.

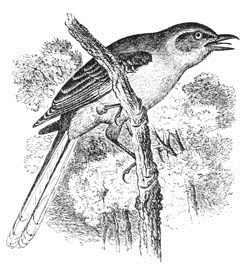

Mimus polyglottus, BoieMOCKING-BIRDTurdus polyglottus, Linn. Syst. Nat. 10th ed. 1758, 169; 12th ed. 1766, 293.—Mimus polyglottus, Boie, Isis, 1826, 972.—Sclater, P. Z. S. 1856, 212.—Ib. 1859, 340.—Ib. Catal. 1861, 8, No. 51.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 344.—Ib. Rev. 48.—Samuels, 167.—Cooper, Birds Cal. 1, 21.—Gundlach, Repertorio, 1865, 230 (Cuba).—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 230.—Coues, Pr. A. N. Sc. 1866, 65 (Arizona).—? Orpheus leucopterus, Vigors, Zoöl. Beechey, 1839.

Figures: Wilson, Am. Orn. II, 1810, pl. x, fig. 1.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1831, pl. xxi.—Ib. Birds Amer. II, 1841, pl. 137.

Sp. Char. Third and fourth quills longest; second about equal to eighth; the first half or more than half the second. Tail considerably graduated. Above ashy brown, the feathers very obsoletely darker centrally, and towards the light plumbeous downy basal portion (scarcely appreciable, except when the feathers are lifted). The under parts are white, with a faint brownish tinge, except on the chin, and with a shade of ash across the breast. There is a pale superciliary stripe, but the lores are dusky. The wings and tail are dark brown, nearly black, except the lesser wing-coverts, which are like the back; the middle and greater tipped with white, forming two bands; the basal portion of the primaries white; most extended on the inner primaries. The outer tail-feather is white, sometimes a little mottled; the second is mostly white, except on the outer web and towards the base; the third with a white spot on the end; the rest, except the middle, very slightly or not at all tipped with white. The bill and legs are black. Length, 9.50; wing, 4.50; tail, 5.00.

Mimus polyglottus.

Young. Similar, but distinctly spotted with dusky on the breast, and obsoletely on the back.

Hab. North America, from about 40° (rare in Massachusetts, Samuels), south to Mexico. Said to occur in Cuba.

The Mocking-Birds are closely allied, requiring careful comparison to distinguish them. A near ally is M. orpheus, of Jamaica, but in this the outer feather is white, and the 2d, 3d, and 4th tail-feathers are marked like the 1st, 2d, and 3d of polyglottus, respectively.

We have examined one hundred and fourteen specimens, of the present species, the series embracing large numbers from Florida, the Rio Grande, Cape St. Lucas, and Mazatlan, and numerous specimens from intermediate localities. The slight degree of variation manifested in this immense series is really surprising; we can discover no difference of color that does not depend on age, sex, season, or the individual (though the variations of the latter kind are exceedingly rare, and when noticed, very slight). Although the average of Western specimens have slightly longer tails than Eastern, a Florida example (No. 54,850, ♂, Enterprise, Feb. 19), has a tail as long as that of the longest-tailed Western one (No. 8,165, Fort Yuma, Gila River, Dec.). Specimens from Colima, Mirador, Orizaba, and Mazatlan are quite identical with Northern ones.

Habits. The Mocking-Bird is distributed on the Atlantic coast, from Massachusetts to Florida, and is also found to the Pacific. On the latter coast it exhibits certain variations in forms, but hardly enough to separate it as a distinct species. It is by no means a common bird in New England, but instances of its breeding as far north as Springfield, Mass., are of constant occurrence, and a single individual was seen by Mr. Boardman near Calais, Me. It is met with every year, more or less frequently, on Long Island, and is more common, but by no means abundant, in New Jersey. It is found abundantly in every Southern State, and throughout Mexico. It has also been taken near Grinnell, Iowa.

A warm climate, a low country, and the vicinity of the sea appear to be most congenial to their nature. Wilson found them less numerous west of the Alleghany than on the eastern side, in the same parallels. Throughout the winter he met with them in the Southern States, feeding on the berries of the red cedar, myrtle, holly, etc., with which the swampy thickets abounded. They feed also upon winged insects, which they are very expert in catching. In Louisiana they remain throughout the entire year, approaching farmhouses and plantations in the winter, and living about the gardens and outhouses. They may be frequently seen perched upon the roofs of houses and on the chimney-tops, and are always full of life and animation. When the weather is mild the old males may be heard singing with as much spirit as in the spring or summer. They are much more familiar than in the more northern States. In Georgia they do not begin to sing until February.

The vocal powers of the Mocking-Bird exceed, both in their imitative notes and in their natural song, those of any other species. Their voice is full, strong, and musical, and capable of an almost endless variation in modulation. The wild scream of the Eagle and the soft notes of the Bluebird are repeated with exactness and with apparently equal facility, while both in force and sweetness the Mocking-Bird will often improve upon the original.

The song of the Mocking-Bird is not altogether imitative. His natural notes are bold, rich, and full, and are varied almost without limitation. They are frequently interspersed with imitations, and both are uttered with a rapidity and emphasis that can hardly be equalled.

The Mocking-Bird readily becomes accustomed to confinement, and loses little of the power, energy, or variety of its song, but often much of its sweetness in a domesticated state. The mingling of unmusical sounds, like the crowing of cocks, the cackling of hens, or the creaking of a wheelbarrow, while they add to the variety, necessarily detracts from the beauty of his song.

The food of the Mocking-Bird is chiefly insects, their larvæ, worms, spiders, etc., and in the winter of berries, in great variety. They are said to be very fond of the grape, and to be very destructive to this fruit. Mr. G. C. Taylor (Ibis, 1862, p. 130) mentions an instance that came to his knowledge, of a person living near St. Augustine, Florida, who shot no less than eleven hundred Mocking-Birds in a single season, and buried them at the roots of his grape-vines.

Several successful attempts have been made to induce the Mocking-Bird to rear their young in a state of confinement, and it has been shown to be, by proper management, perfectly practicable.

In Texas and Florida the Mocking-Bird nests early in March, young birds appearing early in April. In Georgia and the Carolinas they are two weeks later. In Pennsylvania they nest about the 10th of May, and in New York and New England not until the second week of June. They select various situations for the nest; solitary thorn-bushes, an almost impenetrable thicket of brambles, an orange-tree, or a holly-bush appear to be favorite localities. They often build near the farm-houses, and the nest is rarely more than seven feet from the ground. The base of the nest is usually a rudely constructed platform of coarse sticks, often armed with formidable thorns surrounding the nest with a barricade. The height is usually 5 inches, with a diameter of 8. The cavity is 3 inches deep and 5 wide. Within the external barricade is an inner nest constructed of soft fine roots.

The eggs, from four to six in number, vary in length from .94 to 1.06 inches, with a mean length of .99. Their breadth varies from .81 to .69 of an inch, mean breadth .75. They also exhibit great variations in the combinations of markings and tints. The ground color is usually light greenish-blue, varying in the depth of its shade from a very light tint to a distinct blue, with a slight greenish tinge. The markings consist of yellowish-brown and purple, chocolate-brown, russet, and a very dark brown.

Genus GALEOSCOPTES, CabanisGaleoscoptes, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. I, 1850, 82. (Type Muscicapa carolinensis, L.)

Gen. Char. Bill shorter than the head, rather broad at base. Rictal bristles moderately developed, reaching to the nostrils. Wings a little shorter than the tail, rounded; secondaries well developed; fourth and fifth quills longest; third and sixth little shorter; first and ninth about equal, and about the length of secondaries; first quill more than half the second, about half the third. Tail graduated; lateral feather about .70 shorter than the middle. Tarsi longer than middle toe and claw by about an additional half-claw; scutellate anteriorly, more or less distinctly in different specimens; scutellæ about seven.

The conspicuous naked membranous border round the eye of some Thrushes, with the bare space behind it, not appreciable.

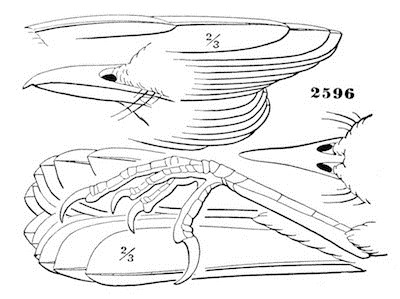

Galeoscoptes carolinensis.

2596

There is little difference in form between the single species of Galeoscoptes and Mimus polyglottus, beyond the less degree of definition of the tarsal plates; and but for the difference in coloration (uniform plumbeous instead of gray above and white beneath), we would hardly be inclined to distinguish the two generically.

The single species known is lead-colored, with black cap, and chestnut-red under tail-coverts.

Galeoscoptes carolinensis, CabanTHE CATBIRDMuscicapa carolinensis, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 328. Turdus carolinensis, Licht. Verz. 1823, 38.—D’Orbigny, La Sagra’s Cuba, Ois. 1840, 51. Orpheus carolinensis, Jones, Nat. Bermuda, 1859, 27 (breeds). Mimus carolinensis, Gray, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1859, 346.—Bryant, Pr. Bost. Soc. 1867, 69 (Inagua).—Lord, Pr. R. Art. Inst. (Woolwich), IV, 1864, 117 (east of Cascade Mts.). Galeoscoptes carolinensis, Cab. Mus. Hein. I, 1850, 82 (type of genus).—Ib. Jour. Orn. 1855, 470 (Cuba).—Gundlach, Repert. 1865, 230 (Cuba, very common).—Sclater, Catal. Birds, 1861, 6, no. 39.—Scl. & Salv. Pr. 1867, 278 (Mosquito Coast).—Baird, Rev. 1864, 54.—Samuels, 172.—Cooper, Birds Cal. 1, 23.

Figures: Aud. B. A. II, pl. 140.—Ib. Orn. Biog. II, pl. 28.—Vieillot, Ois. Am. Sept. II, pl. lxvii.—Wilson, Am. Orn. II, pl. xiv, f. 3.

Sp. Char. Third quill longest; first shorter than sixth. Prevailing color dark plumbeous, more ashy beneath. Crown and nape dark sooty-brown. Wings dark brown, edged with plumbeous. Tail greenish-black; the lateral feathers obscurely tipped with plumbeous. The under tail-coverts dark brownish-chestnut. Female smaller. Length, 8.85; wing, 3.65; tail, 4.00; tarsus, 1.05.

Galeoscoptes carolinensis.

Hab. United States, north to Lake Winnipeg, west to head of Columbia, and Cascade Mountains (Lord); south to Panama R. R.; Cuba; Bahamas; Bermuda (breeds). Accidental in Heligoland Island, Europe. Oaxaca, Cordova, and Guatemala, Sclater; Mosquito Coast, Scl. & Salv.; Orizaba (winter), Sumichrast; Yucatan, Lawr.

Western specimens have not appreciably longer tails than Eastern. Central American examples, as a rule, have the plumbeous of a more bluish cast than is usually seen in North American skins.

Habits. The Catbird has a very extended geographical range. It is abundant throughout the Atlantic States, from Florida to Maine; in the central portion of the continent it is found as far north as Lake Winnepeg.

On the Pacific coast it has been met with at Panama, and also on the Columbia River. It is occasional in Cuba and the Bahamas, and in the Bermudas is a permanent resident. It is also found during the winter months abundant in Central America, It breeds in all the Southern States with possibly the exception of Florida. In Maine, according to Professor Verrill, it is as common as in Massachusetts, arriving in the former place about the 20th of May, about a week later than in the vicinity of Boston, and beginning to deposit its eggs early in June. Near Calais it is a less common visitant.

The Northern migrations of the Catbird commence early in February, when they make their appearance in Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas. In April they reach Virginia and Pennsylvania, and New England from the 1st to the 10th of May. Their first appearance is usually coincident with the blossoming of the pear-trees. It is not generally a popular or welcome visitant, a prejudice more or less wide spread existing in regard to it. Yet few birds more deserve kindness at our hands, or will better repay it. From its first appearance among us, almost to the time of departure in early fall, the air is vocal with the quaint but attractive melody, rendered all the more interesting from the natural song being often blended with notes imperfectly mimicked from the songs of other birds. The song, whether natural or imitative, is always varied, attractive, and beautiful.

The Catbird, when once established as a welcome guest, soon makes itself perfectly at home. He is to be seen at all times, and is almost ever in motion. They become quite tame, and the male bird will frequently apparently delight to sing in the immediate presence of man. Occasionally they will build their nest in close proximity to a house, and appear unmindful of the presence of the members of the family.

The Catbird’s power of mimicry, though limited and imperfectly exercised, is frequently very amusing. The more difficult notes it rarely attempts to copy, and signally fails whenever it does so. The whistle of the Quail, the cluck of a hen calling her brood, the answer of the young chicks, the note of the Pewit Flycatcher, and the refrain of Towhee, the Catbird will imitate with so much exactness as not to be distinguished from the original.

The Catbirds are devoted parents, sitting upon their eggs with great closeness, feeding the young with assiduity, and accompanying them with parental interest when they leave the nest, even long after they are able to provide for themselves. Intruders from whom danger is apprehended they will boldly attack, attempting to drive away snakes, cats, dogs, and sometimes even man. If these fail they resort to piteous cries and other manifestations of their great distress.

Towards each other they are affectionate and devoted, mutually assisting in the construction of the nest; and as incubation progresses the female, who rarely leaves the nest, is supplied with food, and entertained from his exhaustless vocabulary of song, by her mate. When annoyed by an intruder the cry of the Catbird is loud, harsh, and unpleasant, and is supposed to resemble the outcry of a cat, and to this it owes its name. This note it reiterates at the approach of any object of its dislike or fear.

The food of the Catbird is almost exclusively the larvæ of the larger insects. For these it searches both among the branches and the fallen leaves, as well as the furrows of newly ploughed fields and cultivated gardens. The benefit it thus confers upon the farmer and the horticulturist is very great, and can hardly be overestimated.

The Catbird can with proper painstaking be raised from the nest, and when this is successfully accomplished they become perfectly domesticated, and are very amusing pets.