полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 1

Habits. Mr. R. Swinhoe, who describes this among the birds of Formosa as P. sylvicultrix, states it to be a summer visitant to Southern China, passing in large numbers through Amoy in its autumnal migrations southeastward, probably to the Philippine Islands, touching at Southwestern Formosa and Twaiwanfoo, where he found them abundant. This was for a few days in October, but he neither saw any before nor afterwards, nor did he meet with any at Tamsuy (Ibis, 1863, p. 307). The same writer (Ibis, 1860, p. 53) speaks of this bird as very abundant in Amoy during the months of April and May, but passing farther north to breed.

We have no information in reference to its habits, and nothing farther in regard to its distribution. As it bears a very close resemblance to the Willow Wren of Europe, P. trochilus, it is quite probable that its general habits, nest, and eggs will be found to correspond very closely with those of that bird.

The European warblers of the genus Phyllopneuste are all insect-eating birds, capturing their prey while on the wing, and also feeding on their larvæ. They frequent the woodlands during their breeding-season, but at all other times are much more familiar, keeping about dwellings and sheepfolds.

The P. trochilus is a resident throughout the entire year in Southern Europe and in Central Asia. That species builds at the foot of a bush on the ground, and constructs a domed nest with the entrance on one side. Their eggs are five in number, have a pinkish-white ground, and are spotted with well-defined blotches of reddish-brown, measuring 0.65 by 0.50 inch, and are of a rounded oval shape.

Subfamily REGULINÆ

Char. Wings longer than the emarginated tail. Tarsi booted, or without scutellar divisions.

This subfamily embraces but a single well-defined North American genus.

Genus REGULUS, CuvRegulus, Cuv. “Leçons d’Anat. Comp. 1799, 1800.” (Type Motacilla regulus, Linn.)

Reguloides, Blyth. 1847. (Type “R. proregulus, Pall.” Gray.)

Phyllobasileus, Cab. Mus. Hein. I, 1850, 33. (Type Motacilla calendula, Linn.)—Corthylio, Cab. Jour. Orn. I, 1853, 83. (Same type.)

Regulus satrapa.

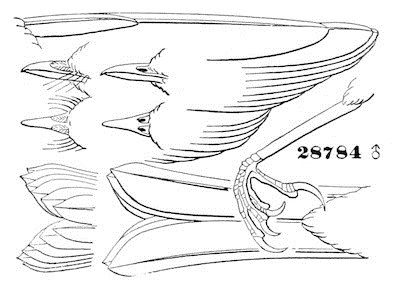

28784. ♂

Gen. Char. Bill slender, much shorter than the head, depressed at base, but becoming rapidly compressed; moderately notched at tip. Culmen straight to near the tip, then gently curved. Commissure straight; gonys convex. Rictus well provided with bristles; nostril covered by a single bristly feather directed forwards (not distinct in calendula). Tarsi elongated, exceeding considerably the middle toe, and without scutellæ. Lateral toes about equal; hind toe with the claw, longer than the middle one by about half the claw. Claws all much curved. First primary about one third as long as the longest; second equal to fifth or sixth. Tail shorter than the wings, moderately forked, the feathers acuminate. Colors olive-green above, whitish beneath. Size very small.

We are unable to appreciate any such difference between the common North American Reguli as to warrant Cabanis in establishing a separate genus for the calendula. The bristly feather over the nostril is perhaps less compact and close, but it exists in a rudimentary condition.

The following synopsis will serve as diagnoses of the species:—

Head with entire cap in adult plain olivaceous, with a concealed patch of crimson. Hab. Whole of North America; south to Guatemala; Greenland … calendula.

Head with forehead and line over the eye white, bordered inside by black, and within this again is yellow, embracing an orange patch in the centre of the crown. Hab. Whole of North America … satrapa.

Head with forehead and line through the eye black, bordered inside by whitish, and within this again by black, embracing an orange-red patch in the centre of the crown. Hab. Banks of Schuylkill River, Pennsylvania … cuvieri.

Regulus satrapa, LichtGOLDEN-CROWNED KINGLETRegulus satrapa, Licht. Verz. 1823, No. 410.—Dall & Bannister (Alaska).—Lord (Vancouver Isl.).—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1859, 227; Review, 65.—Sclater, P. Z. S. 1857, 212 (Orizaba).—Bædeker, Cab. Jour. IV, 33, pl. i, fig. 8 (eggs, from Labrador).—Pr. Max. Cab. Jour. 1858, 111.—Cooper & Suckley, P. R. R. R. XII, II, 1859, 174 (winters in W. Territory).—Lord, R. Art. Inst. Wool. 1864, 114 (nest?).—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 476 (Texas, winter).—Samuels, 179.—Cooper, Birds Cal. 1, 32. Sylvia regulus, Wils.; Regulus cristatus, Vieill.; R. tricolor, Nutt., Aud.

Figures: Aud. Birds Am. II, pl. cxxxii.—Ib. Orn. Biog. II, pl. clxxxiii.—Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. II, pl. cvi.

Sp. Char. Above olive-green, brightest on the outer edges of the wing; tail-feathers tinged with brownish-gray towards the head. Forehead, a line over the eye and a space beneath it, white. Exterior of the crown before and laterally black, embracing a central patch of orange-red, encircled by gamboge-yellow. A dusky space around the eye. Wing-coverts with two yellowish-white bands, the posterior covering a similar band on the quills, succeeded by a broad dusky one. Under parts dull whitish. Length under 4 inches; wing, 2.25; tail, 1.80. Female without the orange-red central patch. Young birds without the colored crown.

Hab. North America generally. On the west coast, not recorded south of Fort Crook. Orizaba, Sclater; W. Arizona, Coues.

Regulus satrapa.

Specimens of this bird from the far West are much brighter and more olivaceous above; the markings of the face are also somewhat different in showing less dusky about the eye. These may form a variety olivaceus.

The Regulus cristatus of Europe, a close ally of our bird, is distinguished by having shorter wings and longer bill; the flame-color of the head is more extended, the black border is almost wanting anteriorly. The back and rump, too, are more yellow.

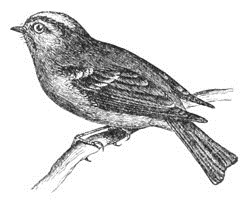

Habits. The Golden-crested Kinglet, or Wren, as it is often called, occurs over nearly the whole of the North American continent. It is abundant from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and throughout the British Provinces, where it chiefly occurs in its breeding-season. In Massachusetts it is a winter resident from October until May. In Maine it is met with in spring and fall, chiefly as a migratory visitor; a few also remain, and probably breed, in the dense Thuja swamps of that State. They are most abundant in April, and again in October. In the vicinity of Calais the Golden-crest is a common summer resident, and, without doubt, breeds there.

Dr. Woodhouse mentions finding this species in abundance in New Mexico and Texas, associated with Nuthatches and Titmice. Dr. Cooper found it abundant in Washington Territory, particularly in the winter, and ascertained positively that they breed there, by seeing them feeding their young near Puget Sound, in the month of August. According to Mr. Ridgway it is much less numerous in the Great Basin than the R. calendula.

The food of this lively and attractive little bird during the summer months is almost exclusively the smaller winged insects, which it industriously pursues amid the highest tree-tops of the forest. At other seasons its habits are more those of the titmice, necessity leading it to ransack the crevices of the bark on the trunks and larger limbs of the forest-trees. It is an expert fly-catcher, taking insects readily upon the wing.

But little is known with certainty regarding its breeding-habits, and its nest and eggs have not yet been described. The presumption, however, is that it builds a pensile nest, not unlike the European congener, and lays small eggs finely sprinkled with buff-colored dots on a white ground, and in size nearly corresponding with those of our common Humming-Bird. We must infer that it raises two broods in a season, from the fact that it spends so long a period, from April to October, in its summer abode, and still more because while Mr. Nuttall found them feeding their full-fledged young in May, on the Columbia, Dr. Cooper, in the same locality, and Mr. Audubon, in Labrador, observed them doing the same thing in the month of August.

According to the observations of Mr. J. K. Lord, this species is very common on Vancouver’s Island and along the entire boundary line separating Washington Territory from British Columbia, where he met with them at an altitude of six thousand feet. He states that they build a pensile nest suspended from the extreme end of a pine branch, and that they lay from five to seven eggs. These he does not describe.

Most writers speak of this Kinglet as having no song, its only note being a single chirp. But in this they are certainly greatly in error. Without having so loud or so powerful a note as the Ruby-crown (R. calendula), for its song will admit of no comparison with the wonderful vocal powers of that species, it yet has a quite distinctive and prolonged succession of pleasing notes, which I have heard it pour forth in the midst of the most inclement weather in February almost uninterruptedly, and for quite an interval.

Bischoff obtained a large number of this species at Kodiak, and also at Sitka, where it seemed to replace the Ruby-crown.

Regulus cuvieri, AudCUVIER’S KINGLETRegulus cuvieri, Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1832, 288, pl. lv, etc.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1859, 228; Rev. Am. Birds, 66.

Sp. Char. Size and general appearance probably that of R. satrapa. A black band on the forehead passing back, through and behind the eye, separated by a grayish band from another black band on the crown, which embraces in the centre of the crown an orange patch. Length, 4.25 inches; extent of wings, 6.

Hab. “Banks of Schuylkill River, Penn. June, 1812.” Aud.

This species continues to be unknown, except from the description of Mr. Audubon, as quoted above. It appears to differ mainly from R. satrapa in having two black bands (not one) on the crown anteriorly, separated by a whitish one; the extreme forehead being black instead of white, as in satrapa. The specimen was killed in June, 1812, on the banks of the Schuylkill River, in Pennsylvania.

Regulus calendula, LichtRUBY-CROWNED KINGLETMotacilla calendula, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 337. Regulus calendula, Licht. Verz. 1823, No. 408.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 226; Rev. 66.—Sclater, P. Z. S. 1857, 202.—Ib. 1858, 300 (mountains of Oaxaca).—Ib. 1859, 362 (Xalapa).—Ib. 1864, 172 (City of Mex.).—Samuels, 178.—Dall & Bannister (Alaska).—Cooper, Birds Cal. 1, 33.—Ib. Ibis, I, 1859, 8 (Guatemala).—Cooper & Suckley, P. R. R. XII, II, 1859, 174.—Reinhardt, Ibis, 1861, 5 (Greenland).—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 475 (Texas, winter). Corthylio calendula, Cab. Jour. Orn. I, 1853, 83 (type of genus). Regulus rubineus, Vieill. Ois. Am. Sept. II, 1807, 49, pl. civ, cv.

Other figures: Wils. Am. Orn. I, 1808, pl. v, fig. 3.—Doughty, Cab. II, pl. vi.—Aud. Orn. Biog. II, pl. cxcv.—Ib. Birds Am. II, pl. cxxxiii.

Sp. Char. Above dark greenish-olive, passing into bright olive-green on the rump and outer edges of the wings and tail. The under parts are grayish-white tinged with pale olive-yellow, especially behind. A ring round the eye, two bands on the wing-coverts, and the exterior of the inner tertials white. Male. Crown with a large concealed patch of scarlet feathers, which are white at the base. Female and young without the red on the crown. Length, 4.50; wing, 2.33; tail, 1.85.

Hab. Greenland; whole of North America, and south to Guatemala. Oaxaca (high region, November), Sclater. Xalapa and Guatemala, Sclater.

This species of Regulus appears to lack the small feather which, in satrapa, overlies and conceals the nostrils, which was probably the reason with Cabanis and Blyth for placing it in a different genus. There is no other very apparent difference of form, however, although this furnishes a good character for distinguishing between young specimens of the two species.

Habits. Much yet remains to be learned as to the general habits, the nesting, and distribution during the breeding-season of the Ruby-crowned Kinglet. It is found, at varying periods, in all parts of North America, from Mexico to the shores of the Arctic seas, and from the Atlantic to the Pacific; and, although its breeding-places are not known, its occurrence in the more northern latitudes, from Maine to the extreme portions of the continent, during the season of reproduction, indicate pretty certainly its extended distribution throughout all the forests from the 44th parallel northward. None of our American ornithologists are known to have met with either its eggs or its nest, but we may reasonably infer that its nest is pensile, like that of its European kindred, and from being suspended from the higher branches, from its peculiar structure and position has thus far escaped observation.

In the New England States they are most abundant in the months of October and April. A few probably remain in the thick evergreen woods throughout the winter, and in the northern parts of Maine they are occasionally found in the summer, and, without doubt, breed there. In the damp swampy woods of the islands in the Bay of Fundy, the writer heard their remarkable song resounding in all directions throughout the month of June.

The song of this bird is by far the most remarkable of its specific peculiarities. Its notes are clear, resonant, and high, and constitute a prolonged series, varying from the lowest tones to the highest, terminating with the latter. It may be heard at quite a distance, and in some respects bears more resemblance to the song of the English Skylark than to that of the Canary, to which Mr. Audubon compares it.

Their food appears to be chiefly the smaller insects, in pursuit of which they are very active, and at times appear to be so absorbed in their avocation as to be unmindful of the near presence of the sportsman or collector, and unwarned by the sound of the deadly gun. They are also said by Wilson to feed upon the stamens of the blossoms of the maple, the apple, peach, and other trees. Like the other species, they are expert insect-takers, catching them readily on the wing. They are chiefly to be met with in the spring among the tree-tops, where the insects they prefer abound among the expanding buds. In the fall of the year, on their return, they are more commonly met with among lower branches, and among bushes near the ground.

Although presumed to be chiefly resident, during the summer months, of high northern regions, Wilson met with specimens in Pennsylvania during the breeding-season; and it is quite probable that they may occur, here and there, among the high valleys in the midst of mountain ranges, in different parts of the country.

In the winter it is most abundant in the Gulf States, and especially in that of Louisiana. Dr. Woodhouse found it quite abundant throughout Texas, New Mexico, and the Indian Territory. Dr. Cooper found it in Washington Territory, but did not there meet with it in summer. Dr. Suckley, however, regarded it as a transient visitor, rather than a winter resident of that region, and far more abundant from about the 8th of April to the 20th of May, when it seemed to be migrating, than at any other time.

Dr. Kennerly found these birds in abundance near Espia, Mexico, and afterwards, during January, among the Aztec Mountains, and again, in February, along the Bill Williams Fork. He describes them as lively, active, and busy in the pursuit of their insect food. They seem to be equally abundant at this season in California, Arizona, and Colorado.

Mr. Ridgway found them common in June and July among the coniferous woods high upon the Wahsatch Mountains in Utah, and has no doubt that they breed there.

Mr. Dall found this species abundant at Nulato, Alaska, in the spring of 1868, preferring the thickets and alder-bushes away from the river-bank. They appeared very courageous. A pair that seemed about to commence building a nest in a small clump of bushes tore to pieces one half finished, belonging to a pair of Scolecophagus ferrugineus, and, on the blackbirds’ return, attacked the female and drove her away. This was early in June, and Mr. Dall was compelled to leave without being able to witness the sequel of the contest.

A straggling specimen of this bird was taken in 1860 at Nenortatik, in Greenland, and sent in the flesh to Copenhagen.

Subfamily POLIOPTILINÆ

The characters of this subfamily will be found on page 69.

Genus POLIOPTILA, SclatPolioptila, Sclater, Pr. Zoöl. Soc. 1855, 11. (Type, Motacilla cærulea.)

Polioptila cærulea.

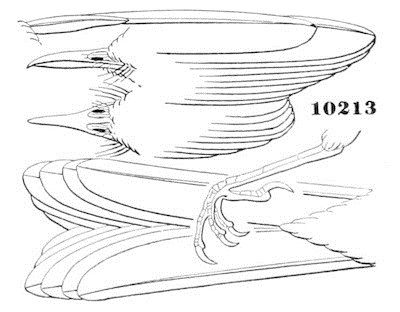

10213

Char. Bill slender, attenuated, but depressed at the base; nearly as long as the head, distinctly notched at the tip, and provided with moderate rictal bristles. Nostrils rather elongated, not concealed, but anterior to the frontal feathers. Tarsi longer than the middle toe, distinctly scutellate; the toes small; the hinder one scarcely longer than the lateral; its claw scarcely longer than the middle. Outer lateral toe longer than the inner. First primary about one third the longest; second equal to the seventh. Tail a little longer than the wings, moderately graduated; the feathers rounded. Nest felted and covered with moss or lichens. Eggs greenish-white, spotted with purplish-brown.

The species all lead-color above; white beneath, and to a greater or less extent on the exterior of the tail, the rest of which is black. Very diminutive in size (but little over four inches long).

Synopsis of SpeciesTop of head plumbeousTwo outer tail-feathers entirely white. A narrow frontal line, extending back over the eye, black. Hab. North America … P. cærulea.

Outer tail-feather, with the whole of the outer web (only), white. No black on the forehead, but a stripe over the eye above one of whitish. Hab. Arizona … P. plumbea.

Top of head blackEdge only of outer web of outer tail-feather white. Entire top of head from the bill black. Hab. Rio Grande and Gila … P. melanura.

Species occur over the whole of America. One, P. lembeyi, is peculiar to Cuba, and a close ally of P. cærulea.

Polioptila cærulea, SclatBLUE-GRAY GNATCATCHER; EASTERN GNATCATCHERMotacilla cærulea, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 337 (based on Motacilla parva cærulea, Edw. tab. 302). Culicivora cærulea, Cab. Jour. 1855, 471 (Cuba).—Gundlach, Repert. 1865, 231. Polioptila cærulea, Sclater, P. Z. S. 1855, 11.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 380.—Ib. Rev. 74.—Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 231.—Cooper, Birds Cal. 1, 35. Motacilla cana, Gm. S. N. I, 1788, 973. ? Culicivora mexicana, Bon. Consp. 1850, 316 (not of Cassin), female. Polioptila mexicana, Sclater, P. Z. S. 1859, 363, 373.

Figures: Vieill. Ois. II, pl. lxxxviii.—Wilson, Am. Orn. II, pl. xviii, fig. 3.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, pl. lxxxiv; Ib. Birds Am. I, pl. lxx.

Sp. Char. Above grayish-blue, gradually becoming bright blue on the crown. A narrow frontal band of black extending backwards over the eye. Under parts and lores bluish-white tinged with lead-color on the sides. First and second tail-feathers white except at the extreme base, which is black, the color extending obliquely forward on the inner web; third and fourth black, with white tip, very slight on the latter; fifth and sixth entirely black. Upper tail-coverts blackish-plumbeous. Quills edged externally with pale bluish-gray, which is much broader and nearly white on the tertials. Female without any black on the head. Length, 4.30; wing, 2.15; tail, 2.25. (Skin.)

Hab. Middle region of United States, from Atlantic to Pacific, and south to Guatemala; Cape St. Lucas. Cuba, Gundlach and Bryant. Bahamas, Bryant.

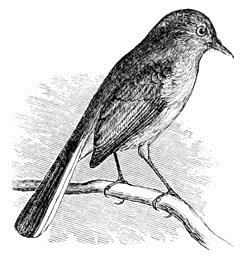

Habits. The Blue-gray Flycatcher is a common species from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast, although not met with in the New England States. It is less abundant on the coast than at a distance from it, and has a more northern range in the interior, being met with in Northern Ohio, Michigan, and the British Provinces. Specimens occur in the Smithsonian Institution collection from New York to Mexico and Guatemala, and from Washington Territory to California.

They appear in Pennsylvania early in May, and remain there until the last of September. They are observed in Florida and Georgia early in March, but are not known to winter in that latitude. All the specimens in the Smithsonian collection were obtained between April and October, except one from Southern California, which was taken in December.

Polioptila cærulea.

Near Washington, Dr. Coues states the Blue-gray Gnatcatcher to be a summer resident, arriving during the first week of April, and remaining until the latter part of September, during which time they are very abundant. They are said to breed in high open woods, and, on their first arrival, to frequent tall trees on the sides of streams and in orchards.

In California and Arizona this species occurs, but is, to some extent, replaced by a smaller species, peculiarly western, P. melanura. There they seem to keep more about low bushes, hunting minute insects in small companies or in pairs, and their habits are hardly distinguishable from those of Warblers in most respects.

The food of this species is chiefly small winged insects and their larvæ. It is an expert insect-catcher, taking its prey on the wing with great celerity. All its movements are very rapid, the bird seeming to be constantly in motion as if ever in quest of insects, moving from one part of the tree to the other, but generally preferring the upper branches.

Nuttall and Audubon, copying Wilson, speak of the nest of this Gnatcatcher as a very frail receptacle for its eggs, and as hardly strong enough to bear the weight of the parent bird. This, however, all my observations attest to be not the fact. The nest is, on the contrary, very elaborately and carefully constructed; large for the size of the bird, remarkably deep, and with thick, warm walls composed of soft and downy materials, but abundantly strong for its builder, who is one of our smallest birds both in size and in weight. Like the nests of the Wood Pewee and the Humming-Bird, they are models of architectural beauty and ingenious design. With walls made of a soft felted material, they are deep and purse-like. They are not pensile, but are woven to small upright twigs, usually near the tree-top, and sway with each breeze, but the depth of the cavity and its small diameter prevent the eggs from rolling out. Externally the nest is covered with a beautiful periphery of gray lichens, assimilating it to the bark of the deciduous trees in which it is constructed.

Occasionally these nests have been found at the height of ten feet from the ground, but they are more frequently built at a much greater elevation, even to the height of fifty feet or more. They are made in the shape of a truncated cone, three inches in diameter at the base and but two at the top, and three and a half inches in height. The diameter of the opening is an inch and a half. In Northern Georgia they nest about the middle of May, and are so abundant that the late Dr. Gerhardt would often find not less than five in a single day, and very rarely were any of them less than sixty feet from the ground. Dr. Gerhardt, who was an accurate and careful observer, speaks of these as the best built nests he had met with in this country, both in regard to strength and its ingeniously contrived aperture, so narrowed at the top that it is impossible for the eggs to roll out even in the severest wind. They have two broods in the season in the Southern States, one in April and again in July.