полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

Mr. Salvin is of the opinion that Humming-Birds do not remain long on the wing at once, but rest frequently, choosing for that purpose a small dead or leafless twig at the top, or just within the branches of the tree. While in this position they trim their feathers and clean their bill, all the time keeping up an incessant jerking of their wings and tail.

In Mexico, where these birds are very abundant, they are attracted by the blossoms of the Agave americana, and swarm around them like so many beetles. As they fly, they skim over the fields, rifle the flowers, mingling with the bees and the butterflies, and during the seasons of bloom, at certain hours of the day, the fields appear perfectly alive with them. The ear receives unceasingly the whistling sounds of their flight, and their shrill cries, resembling in their sharp accent the clash of weapons. Although the Humming-Bird always migrates at the approach of cold weather, yet it is often to be found at very considerable elevations. The traveller Bourcier met with them on the crater of Pichincha, and M. Saussure obtained specimens of Calothorax lucifer in the Sierra de Cuernavaca, at the height of more than 9,500 feet.

While we must accept as a well-established fact that the Humming-Birds feed on insects, demonstrated long since by naturalists, it is equally true that they are very fond of the nectar of flowers, and that this, to a certain extent, constitutes their nourishment. This is shown by the sustenance which captive Humming-Birds receive from honey and other sweet substances, food to which a purely insectivorous bird could hardly adapt itself.

Notwithstanding their diminutive size the Humming-Birds are notorious for their aggressive disposition. They attack with great fury anything that excites their animosity, and maintain constant warfare with whatever is obnoxious to them, expressly the Sphinxes or Hawk-Moths. Whenever one of these inoffensive moths, two or three times the size of a Humming-Bird, chances to come too early into the garden and encounters one of these birds, he must give way or meet with certain injury. At sight of the insect the bird attacks it with his pointed beak with great fury. The Sphinx, overcome in this unlooked-for attack, beats a retreat, but, soon returning to the attractive flowers, is again and again assaulted by its infuriated enemy. Certain destruction awaits these insects if they do not retire from the field before their delicate wings, lacerated in these attacks, can no longer support them, and they fall to the ground to perish from other enemies.

In other things the Humming-Bird also shows itself all the more impertinent and aggressive that it is small and weak. It takes offence at everything that moves near it. It attacks birds much larger than itself, and is rarely disturbed or molested by those it thus assails. All other birds must make way. It is possible that in some of these attacks it may be influenced by an instinctive prompting of advantages to be gained, as in the case of the spider, in whose nets they are liable to be entangled, and whose webs often seriously incommode them. When a Humming-Bird perceives a spider in the midst of its net, it rarely fails to make an attack, and with such rapidity that one cannot follow the movement, but in the twinkling of an eye the spider has disappeared. This is not only done to small spiders, which doubtless they devour, but also to others too large to be thus eaten.

Not content with thus chastising small enemies, the Humming-Bird also contends with others far more powerful, and which give them a good deal of trouble. They have been known to engage in an unequal contest with the Sparrow-Hawk, yet rarely without coming off the conquerors. In this strife they have the advantage of numbers, their diminutive size, and the rapidity and the irregularity of their own movements. Several unite in these attacks, and, in rushing upon their powerful enemy, they always aim at his eyes. The Hawk soon appreciates his inability to contend with these tormenting little furies, and beats an ignominious retreat.

Advantage is taken of this aggressive disposition of these birds, by the hunter, to capture them. In their combats with one another, or in their rash attacks upon various offensive objects, even upon the person of the snarer himself, they are made prisoners through their own rashness and reckless impetuosity.

In enumerating the prominent characteristics of this remarkable family, we should not omit to refer to the lavish profusion of colors of every tint and shade, excelling in lustre and brilliancy even the costliest gems, with which Nature has adorned their plumage. And not only are nearly all the birds of this group thus decked out with hues of the most dazzling brightness and splendor, when alive and resplendent in the tropical sun, but many also display the most wonderfully varying shades and colors, according to the position in which they are presented to the eye. The sides of the fibres of each feather are of a different color from the surface, and change as seen in a front or an oblique direction, and while living, these birds, by their movements, can cause these feathers to change very suddenly to very different hues. Thus the Selasphorus rufus can change in a twinkling the vivid fire-color of its expanded throat to a light green, and the species known as the Mexican Star (Cynanthus lucifer) changes from a bright crimson to an equally brilliant blue.

The nests and the eggs of the Humming-Birds, though in a few exceptional cases differing as to the form and position of the former, are similar, so far as known, in the whole family. The eggs are always two in number, white and unspotted, oblong in shape, and equally obtuse at either end. The only differences to be noticed are in the relative variations in size. The nests are generally saddled upon the upper side of a horizontal branch, are cup-like in shape, and are largely made up of various kinds of soft vegetable down, covered by an outward coating of lichens and mosses fastened upon them by the glue-like saliva of the bird. In T. colubris the soft inner portion of the nest is composed of the delicate downy covering of the leaf-buds of several kinds of oaks. In Georgia the color of this down is of a deep nankeen hue, but in New England it is nearly always white. At first the nest is made of this substance alone, and the entire complement of eggs, never more than two, is sometimes laid before the covering of lichens is put on by the male bird, who seems to amuse himself with this while his mate is sitting upon her eggs.

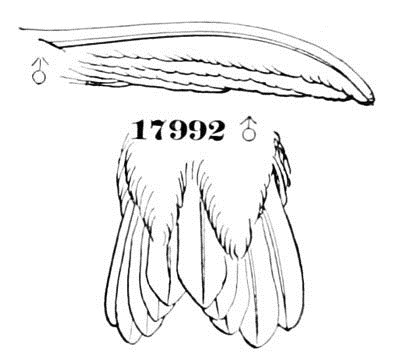

Genus STELLULA, GouldStellula, Gould, Introd. Trochil. 1861, 90. (Type, Trochilus calliope, Gould.)

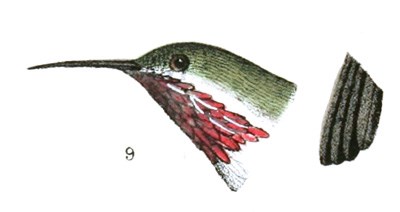

Gen. Char. Bill rather longer than the head; straight. Wings much developed, reaching beyond the tail, which is short, nearly even, or slightly rounded, and with the inner-most feathers abruptly short; the outer feather rather narrower and more linear than the others, which have a rather spatulate form. Metallic throat-feathers elongated and rather linear and loose, not forming a continuous metallic surface. Central tail-feather without green.

Stellula calliope.

17992 ♂

This genus, established by Gould, has a slight resemblance to Atthis, but differs in absence of the attenuated tip of outer primary. The outer three tail-feathers are longest and nearly even (the second rather longest), the fourth and fifth equal and abruptly a little shorter, the latter without any green. The feathers are rather broad and wider terminally (the outermost least so), and are obtusely rounded at end. The tail of the female is quite similar. The absence of green on the tail in the male seems a good character. But one species is known of the genus.

Calothorax is a closely allied genus, in which the tail is considerably longer. One species, C. cyanopogon, will probably be yet detected in New Mexico.

Stellula calliope, GouldTHE CALLIOPE HUMMING-BIRDTrochilus calliope, Gould, Pr. Z. S. 1847, 11 (Mexico). Calothorax calliope, Gray, Genera, I, 100.—Bon. Rev. Mag. Zoöl. 1854, 257.—Gould, Mon. Troch. III, pl. cxlii.—Xantus, Pr. A. N. Sc. 1859, 190.—Elliot, Illust. Birds N. A. I, xxiii. Stellula calliope, Gould, Introd. Troch. 1861, 90.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 1870, 363.

Sp. Char. Male above, except on tail, golden-green, beneath white, the sides glossed with green, the flanks somewhat with rusty; crissum pure white. Throat-feathers pure white at base, terminal half violet-red, more reddish than in Atthis heloisæ; the sides of neck pure white. Tail-feathers brown, edged at base, especially on inner webs, but inconspicuously, with rufous; the ends paler, as if faded; central feathers like the rest; under mandible yellow. Length, 2.75; wing, 1.60; tail, 1.00; bill above to base of feathers, .55. Female without the metallic gorget (replaced by a few dusky specks), and the throat-feathers not elongated; no green on sides, and more tinged with rufous beneath. A white crescent under the eye. Tail more rounded and less emarginate than in the male. The outer three feathers green at base, then black, and tipped with white; the fourth green and black; the fifth green, with a dusky shade at end; all, except central, edged internally at base with rufous. The under mandible is paler at base than elsewhere, but not yellowish-white as in the male.

Hab. Mountains of Washington Territory, Oregon, and California, to Northern Mexico. East to East Humboldt Mountains (Ridgway); Fort Tejon (Xantus); Fort Crook (Feilner).

The male bird is easily distinguished from other North American species by its very small size, the snowy-white bases of the elongated loose throat-feathers, and by the shape of the tail, as also the absence, at least in the several males before us, of decided metallic green on the central tail-feathers. The females resemble those of A. heloisæ most closely, but have longer bills and wings, broader tail-feathers, and their rufous confined to the edges, instead of crossing the entire basal portion. Selasphorus platycercus and rufus are much larger, and have tails marked more as in A. heloisæ.

Habits. This interesting species was first met with as a Mexican Humming-Bird, on the high table-lands of that republic, by Signor Floresi. His specimens were obtained in the neighborhood of the Real del Monte mines. As it was a comparatively rare bird, and only met with in the winter months, it was rightly conjectured to be only a migrant in that locality.

This species is new to the fauna of North America, and was first brought to the attention of naturalists by Mr. J. K. Lord, one of the British commissioners on the Northwest Boundary Survey. It is presumed to be a mountain species, found in the highlands of British Columbia, Washington Territory, Oregon, California, and Northern Mexico.

Early in May Mr. Lord was stationed on the Little Spokan River, superintending the building of a bridge. The snow was still remaining in patches, and no flowers were in bloom except the brilliant pink Ribes, or flowering currant. Around the blossoms of this shrub he found congregated quite a number of Humming-Birds. The bushes seemed to him to literally gleam with their flashing colors. They were all male birds, and of two species; and upon obtaining several of both they proved to be, one the Selasphorus rufus, the other the present species, one of the smallest of Humming-Birds, and in life conspicuous for a frill of minute pinnated feathers, encircling the throat, of a delicate magenta tint, which can be raised or depressed at will. A few days after the females arrived, and the species then dispersed in pairs.

He afterwards ascertained that they prefer rocky hillsides at great altitudes, where only pine-trees, rock plants, and an alpine flora are found. He frequently shot these birds above the line of perpetual snow. Their favorite resting-place was on the extreme point of a dead pine-tree, where, if undisturbed, they would sit for hours. The site chosen for the nest was usually the branch of a young pine, where it was artfully concealed amidst the fronds at the very end, and rocked like a cradle by every passing breeze.

Dr. Cooper thinks that he met with this species in August, 1853, on the summit of the Cascade Mountains, but mistook the specimens for the young of Selasphorus rufus.

Early in June, 1859, Mr. John Feilner found these birds breeding near Pitt River, California, and obtained their nests.

This species was obtained by Mr. Ridgway only on the East Humboldt Mountains, in Eastern Nevada. The two or three specimens shot were females, obtained in August and September, and at the time mistaken for the young of Selasphorus platycercus, which was abundant at that locality.

Dr. W. J. Hoffman writes, in relation to this species, that on the 20th of July, 1871, being in camp at Big Pines, a place about twenty-seven miles north of Camp Independence, California, on a mountain stream, the banks of which are covered with an undergrowth of cottonwood and small bushes, he frequently saw and heard Humming-Birds flying around him. He at length discovered a nest, which was perched on a limb directly over the swift current, where it was sometimes subjected to the spray. The limb was but half an inch in thickness, and the nest was attached to it by means of thin fibres of vegetable material and hairs. It contained two eggs. The parents were taken, and proved to be this species. There were many birds of the same kind at this point, constantly on the tops of the small pines in search of insects.

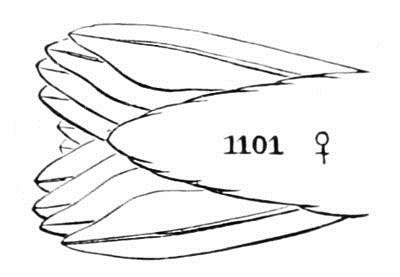

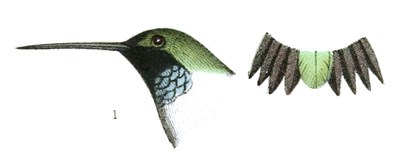

Genus TROCHILUS, LinnæusTrochilus, Linnæus, Systema Naturæ, 1748 (Agassiz).

Trochilus colubris.

1101 ♀

Gen. Char. Metallic gorget of throat nearly even all round. Tail forked; the feathers lanceolate, acute, becoming gradually narrower from the central to the exterior. Inner six primaries abruptly and considerably smaller than the outer four, with the inner web notched at the end.

Trochilus colubris. ♂

1100

The female has the outer tail-feathers lanceolate, as in the male, though much broader. The outer feathers are broad to the terminal third, where they become rapidly pointed, the tip only somewhat rounded; the sides of this attenuated portion (one or other, or both) broadly and concavely emarginated, which distinguishes them from the females of Selasphorus and Calypte, in which the tail is broadly linear to near the end, which is much rounded without any distinct concavity.

A peculiarity is observable in the wing of the two species of Trochilus as restricted, especially in T. colubris, which we have not noticed in other North American genera. The outer four primaries are of the usual shape, and diminish gradually in size; the remaining six, however, are abruptly much smaller, more linear, and nearly equal in width (about that of inner web of the fourth), so that the interval between the fifth and fourth is from two to five times as great as that between the fifth and sixth. The inner web of these reduced primaries is also emarginated at the end. This character is even sometimes seen in the females, but to a less extent, and may serve to distinguish both colubris and alexandri from other allied species where other marks are obscured.

The following diagnosis will serve to distinguish the species found in the United States:—

Common Characters. Above and on the sides metallic green. A ruff of metallic feathers from the bill to the breast, behind which is a whitish collar, confluent with a narrow abdominal stripe; a white spot behind the eye. Tail-feathers without light margins.

Tail deeply forked (.30 of an inch). Throat bright coppery-red from the chin. Tail of female rounded, emarginated … T. colubris.

Larger. Tail slightly forked (.10 of an inch). Throat gorget with violet, steel, green, or blue reflections behind; anteriorly opaque velvety-black. Tail of female graduated; scarcely emarginated … T. alexandri.

Trochilus colubris, LinnæusRUBY-THROATED HUMMING-BIRDTrochilus colubris, Linn. Syst. Nat. I, 1766, 191.—Wilson, Am. Orn. II, 1810, 26, pl. x.—Aud. Orn. Biog. I, 1832, 248, pl. xlvii.—Ib. Birds Am. IV, 1842, 190, pl. ccliii.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 131.—Max. Cab. J. VI, 154.—Samuels, 111.—Allen, B. Fla. 301. Ornisyma colubris, Deville, Rev. et Mag. Zool. May, 1852 (habits). Trochilus aureigaster, Lawrence (alcoholic specimens).

Sp. Char. Tail in the male deeply forked; the feathers all narrow lanceolate-acute. In the female slightly rounded and emarginate; the feathers broader, though pointed. Male, uniform metallic green above; a ruby-red gorget (blackish near the bill), with no conspicuous ruff; a white collar on the jugulum; sides of body greenish; tail-feathers uniformly brownish-violet. Female, without the red on the throat; the tail rounded and emarginate, the inner feathers shorter than the outer; the tail-feathers banded with black, and the outer tipped with white; no rufous or cinnamon on the tail in either sex. Length, 3.25; wing, 1.60; tail, 1.25; bill, .65. Young males are like the females; the throat usually spotted, sometimes with red; the tail is, in shape, more like that of the old male.

Hab. Eastern North America to the high Central Plains; south to Brazil. Localities: Cordova (Scl. P. Z. S. 1856, 288); Guatemala (Scl. Ibis, I, 129); Cuba (Cab. J. IV, 98; Gundl. Rep. I, 1866, 291); S. E. Texas (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 470, breeds); Veragua (Salv. P. Z. S. 1870, 208).

The Trochilus aureigaster (aureigula?) of Lawrence, described from an alcoholic specimen in the Smithsonian collection, differs in having a green throat, becoming golden towards the chin. It is quite probable, however, that the difference is the result of immersion in spirits.

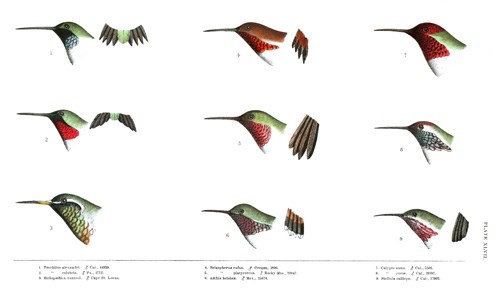

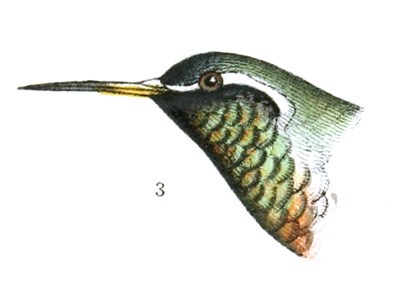

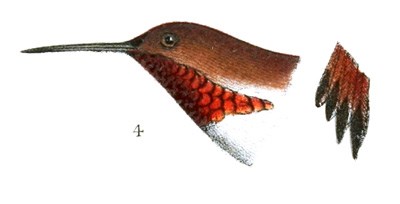

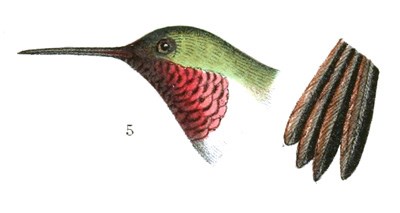

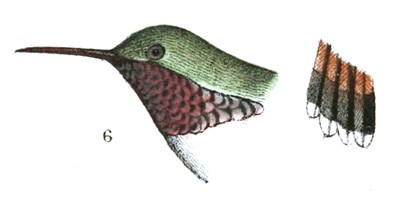

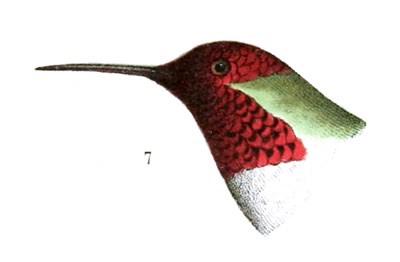

PLATE XLVII.

1. Trochilus alexandri. ♂ Cal., 44959.

2. Trochilus colubris. ♂ Pa., 2713.

3. Heliopædica xantusi. ♂ Cape St. Lucas.

4. Selasphorus rufus. ♂ Oregon, 2896.

5. Selasphorus platycercus. ♂ Rocky Mts., 10847.

6. Atthis heloisæ. ♂ Mex., 25874.

7. Calypte anna. ♂ Cal., 5501.

8. Calypte costæ. ♂ Cal., 39397.

9. Stellula calliope. ♂ Cal., 17992.

The red of the throat appears paler in some Mexican and Guatemalan skins; others, however, are not distinguishable from the northern specimens.

Habits. This species is found throughout eastern North America, as far west as the Missouri Valley, and breeds from Florida and the valley of the Rio Grande to high northern latitudes. Richardson states that it ranges at least to the 57th parallel, and probably even farther north. He obtained specimens on the plains of the Saskatchewan, and Mr. Drummond found one of its nests near the source of the Elk River. Mr. Dresser found this bird breeding in Southwestern Texas, and also resident there during the winter months, and I have received their nests and eggs from Florida and Georgia. It was found by Mr. Skinner to be abundant in Guatemala during the winter months, on the southern slope of the great Cordillera, showing that it chooses for its winter retreat the moderate climate afforded by a region lying between the elevations of three and four thousand feet, where it winters in large numbers. Mr. Salvin noted their first arrival in Guatemala as early as the 24th of August. From that date the number rapidly increased until the first week in October, when it had become by far the most common species about Dueñas. It seemed also to be universally distributed, being equally common at Coban, at San Geronimo, and the plains of Salamá.

The birds of this species make their appearance on our southern border late in March, and slowly move northward in their migrations, reaching Upper Georgia about the 10th of April, Pennsylvania from the last of April to about the middle of May, and farther north the last of May or the first of June. They nest in Massachusetts about the 10th of June, and are about thirteen days between the full number of eggs and the appearance of the young. They resent any approach to their nest, and will even make angry movements around the head of the intruder, uttering a sharp outcry. Other than this I have never heard them utter any note.

Attempts to keep in confinement the Humming-Bird have been only partially successful. They have been known to live, at the best, only a few months, and soon perish, partly from imperfect nourishment and unsuitable food, and probably also from insufficient warmth.

Numerous examinations of stomachs of these birds, taken in a natural state, demonstrate that minute insects constitute a very large proportion of their necessary food. These are swallowed whole. The young birds feed by putting their own bills down the throats of their parents, sucking probably a prepared sustenance of nectar and fragments of insects. They raise, I think, but one brood in a season. The young soon learn to take care of themselves, and appear to remain some time after their parents have left. They leave New England in September, and have all passed southward beyond our limits by November.

A nest of this bird, from Dr. Gerhardt, of Georgia, measures 1.75 inches in its external diameter and 1.50 in height. Its cavity measures 1.00 in depth and 1.25 inches in breadth. It is of very homogeneous construction, the material of which it is made being almost exclusively a substance of vegetable origin, resembling wool, coarse in fibre, but soft, warm, and yielding, of a deep buff color. This is strengthened, on the outside, by various small woody fibres; the whole, on the outer surface, entirely and compactly covered by a thatching of small lichens, a species of Parmelia.

A nest obtained in Lynn, Mass., by Mr. George O. Welch, in June, 1860, was built on a horizontal branch of an apple-tree. It measures 1.50 inches in height, and 2.25 in its external diameter. The cavity is more shallow, measuring .70 of an inch in depth and 1.00 in diameter. It is equally homogeneous in its composition, being made of very similar materials. In this case, however, the soft woolly material of which it is woven is finer in fibre, softer and more silky, and of the purest white color. It is strengthened on the base with pieces of bark, and on the sides with fine vegetable fibres. The whole nest is beautifully covered with a compact coating of lichens, a species of Parmelia, but different from those of the Georgian nest.

The fine silk-like substance of which the nest from Lynn is chiefly composed is supposed to be the soft down which appears on the young and unexpanded leaves of the red-oak, immediately before their full development. The buds of several of the oaks are fitted for a climate liable to severe winters, by being protected by separate downy scales surrounding each leaf. In Massachusetts the red-oak is an abundant tree, expands its leaves at a convenient season for the Humming-Bird, and these soft silky scales which have fulfilled their mission of protection to the embryo leaves are turned to a good account by our tiny and watchful architect. The species in Georgia evidently make use of similar materials from one of the southern oaks.