полная версия

полная версияA History of North American Birds, Land Birds. Volume 2

Dr. Suckley found this species extremely abundant in the open districts on the Columbia River, as well as upon the gravelly prairies of the Puget Sound district. It is not named as having been met with by Mr. Dall or any of the Russian Telegraph party in Alaska.

It was found in abundance during the summer by Mr. Ridgway in all the wooded portions of the country of the Great Basin. He did not meet with any among the cottonwoods of the river-valleys, its favorite haunts appearing to be the cedars and the nut-pines of the mountains. In July and August, in such localities, on the East Humboldt Mountains, it was not only the most numerous species, but also very abundant, nesting in the trees. About the middle of August they congregated in large numbers, preparing for their departure.

At Sacramento it was also very abundant among the groves of small oaks. He could not observe the slightest difference in habits or notes between the eastern and the western specimens of this form. He found them breeding at Salt Lake City, June 19, the nest being in a scrub-oak, six feet from the ground.

In Arizona, Dr. Coues found the Chippy a very abundant summer resident, arriving the third week of March and remaining until the latter part of November. A few may spend the winter there. As described, it seems more gregarious than it is with us, arriving in the spring, and remaining for a month or more in large flocks of fifty or upwards. In New England they always come in pairs, and only assemble in flocks just on the eve of their departure. Mr. Dresser met with these Sparrows, and obtained specimens of them, near San Antonio, on the 10th of April. Dr. Heermann, in his Report upon the birds observed in Lieutenant Williamson’s route between the 32d and 35th parallels, speaks of finding this species abundant.

Dr. Gerhardt found this Sparrow not uncommon in the northern portions of Georgia, where it is resident throughout the year, and where a few remain in the summer to breed. Dr. Coues also states that a limited number summer in the vicinity of Columbia, S. C., but that their number is insignificant compared with those wintering there between October and April. They collect in large flocks on their arrival, and remain in companies of hundreds or more.

Mr. Sumichrast states that it is a resident bird in the temperate region of Vera Cruz, Mexico, where it remains throughout the year, and breeds as freely and commonly as it does within the United States.

Although found throughout the country in greater or less numbers, they are noticeably not common in the more recent settlements of the West, as on the unsettled prairies of Illinois and Iowa. Mr. Allen found them quite rare in both States, excepting only about the older settlements. As early as the first week in April, 1868, I noticed these birds very common and familiar in the streets of St. Louis, especially so in the business part of that city, along the wharves and near the grain-stores, seeking their food on the ground with a confidence and fearlessness quite unusual to it in such situations.

The tameness and sociability of this bird surpass that of any of the birds I have ever met with in New England, and are only equalled by similar traits manifested by the Snowbird (J. hyemalis) in Pictou. Those that live about our dwellings in rural situations, and have been treated kindly, visit our doorsteps, and even enter the houses, with the greatest familiarity and trust. They will learn to distinguish their friends, alight at their feet, call for their accustomed food, and pick it up when thrown to them, without the slightest signs of fear. One pair which, summer after summer, had built their nest in a fir-tree near my door, became so accustomed to be fed that they would clamor for their food if they were any morning forgotten. One of these birds, the female, from coming down to the ground to be fed with crumbs, soon learned to take them on the flat branch of the fir near her nest, and at last to feed from my hand, and afterwards from that of other members of the family. Her mate, all the while, was comparatively shy and distrustful, and could not be induced to receive his food from us or to eat in our presence.

This Sparrow is also quite social, keeping on good terms and delighting to associate with other species. Since the introduction of the European House Sparrow into Boston, I have repeatedly noticed it associating with them in the most friendly relations, feeding with them, flying up with them when disturbed, and imitating all their movements.

The Chipping Sparrow has very slight claims to be regarded as one of our song-birds. Its note of complaint or uneasiness is a simple chip, and its song, at its best, is but a monotonous repetition of a single note, sounding like the rapid striking together of two small pebbles. In the bright days of June this unpretending ditty is kept up incessantly, hours at a time, with only rare intermissions.

The nest of this bird is always in trees or bushes. I have in no instance known of its being built on the ground. Even at the Arctic regions, where so many of our tree-builders vary from this custom to nest on the ground, no exceptional cases are reported in regard to it, all its nests being upon trees or in bushes. These are somewhat rudely built, often so loosely that they may readily be seen through. Externally they are made of coarse stems of grasses and vegetable branches, and lined with the hair of the larger animals.

These birds are devoted parents, and express great solicitude whenever their nests are approached or meddled with. They feed their young almost exclusively with the larvæ of insects, especially with young caterpillars. When in neighborhoods infested with the destructive canker-worm, they will feed their young with this pest in incredible numbers, and seek them from a considerable distance. Living in a district exempt from this scourge, yet but shortly removed from them, in the summer of 1869, I noticed one of these Sparrows with its mouth filled with something which inconvenienced it to carry. It alighted on the gravel walk to adjust its load, and passed on to its nest, leaving two canker-worms behind it, which, if not thus detected, would have introduced this nuisance into an orchard that had previously escaped, showing that though friends to those afflicted they are dangerous to their neighbors. This Sparrow is also the frequent nurse of the Cow Blackbird, rearing its young to the destruction of its own, and tending them with exemplary fidelity.

Their eggs, five in number, are of an oblong-oval shape, and vary greatly in size. They are of a bluish-green color, and are sparingly spotted about the larger end with markings of umber, purple, and dark blackish-brown, intermingled with lighter shadings of faint purple. The largest specimen I have ever noticed of this egg, found in the Capitol Grounds, Washington, measures .80 by .58 of an inch; and the smallest, from Varrell’s Station, Ga., measures .60 by .50. Their average measurement is about .70 by .54. They are all much pointed at the smaller end.

Spizella socialis, var. arizonæ, CouesWESTERN CHIPPING SPARROWSpizella socialis, var. arizonæ, Coues, P. A. N. S. 1866.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 207.

Sp. Char. Similar to socialis, but tail and wing longer, the bill narrower, and colors paler and grayer. Rufous of the crown lighter and less purplish, generally (always in specimens from southern Rocky Mountains) with fine black streaks on the posterior part. Ash of the cheeks paler, throwing the white of the superciliary stripe and throat into less contrast. Black streaks of the back narrower, and without the rufous along their edges, merely streaking a plain light brownish-gray ground-color. A strong ashy shade over the breast, not seen in socialis; wing-bands more purely white. Wing, 3.00; tail, 2.80; bill, .36 from forehead, by .18 deep. (40,813 ♂, April 24, Fort Whipple, Ariz., Dr. Coues.)

Hab. Western United States from Rocky Mountains to the Pacific; south in winter into Middle and Western Mexico.

All the specimens of a large series from Fort Whipple, Arizona, as well as most others from west of the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific coast, agree in the characters given above, as distinguished from eastern specimens of socialis. The variations with age and season are simple parallels of those in socialis.

Habits. The references in the preceding article to the Chipping Sparrow as occurring in the Middle and Western Provinces of the United States, are to be understood as applying to the present race.

Spizella pallida, BonapCLAY-COLORED SPARROWEmberiza pallida, Sw. F. Bor.-Am. II, 1831, 251 (not of Audubon). Spizella pallida, Bonap. List, 1838.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 474. Spinites pallidus, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 133. Emberiza shattucki, Aud. Birds Am. VII, 1843, 347, pl. ccccxciii. Spizella shattucki, Bonap. Conspectus, 1850, 480.

Sp. Char. Smaller than S. socialis. Back and sides of hind neck ashy. Prevailing color above pale brownish-yellow, with a tinge of grayish. The feathers of back and crown streaked conspicuously with blackish. Crown with a median pale ashy and a lateral or superciliary ashy-white stripe. Beneath whitish, tinged with brown on the breast and sides, and an indistinct narrow brown streak on the edge of the chin, cutting off a light stripe above it. Ear-coverts brownish-yellow, margined above and below by dark brown, making three dark stripes on the face. Bill reddish, dusky towards tip. Legs yellow. Length, 4.75; wing, 2.55.

Hab. Upper Missouri River and high central plains to the Saskatchewan country. Cape St. Lucas, Oaxaca, March (Scl. 1859, 379); Fort Mohave (Cooper, P. A. N. S. Cal. 1861, 122); San Antonio, Texas, spring (Dresser, Ibis, 1865, 489; common).

The ashy collar is quite conspicuous, and streaked above with brown. The rump is immaculate. The streaks on the feathers of the crown almost form continuous lines, about six in number. The brown line above the ear-coverts is a post-ocular one. That on the side of the chin forms the lower border of a white maxillary stripe which widens and curves around behind the ear-coverts, fading into the ashy of the neck. The wing-feathers are all margined with paler, and there is an indication of two light bands across the ends of the coverts.

The young of this species is thickly streaked beneath over the throat, breast, and belly, with brown, giving to it an entirely different appearance from the adult. The streaks in the upper parts, too, are darker and more conspicuous. The margins of the feathers are rather more rusty.

This species is readily distinguishable from the other American Spizellas, except S. breweri (which see), in the dark streaks and median ashy stripe on the crown, the paler tints, the dark line on the side of the chin, etc.

Habits. The Clay-colored Bunting was first discovered by Richardson, and described by Swainson, in the Fauna Bor.-Amer. The only statement made in regard to it is that it visited the Saskatchewan in considerable numbers, frequented the farm-yard at Carlton House, and was in all respects as familiar and confiding as the common House Sparrow of Europe.

The bird given by Mr. Audubon as the pallida has been made by Mr. Cassin a different species, S. breweri, and the species the former gives in his seventh volume of the Birds of America as Emberiza shattucki is really this species. It was found by Mr. Audubon’s party to the Yellowstone quite abundant throughout the country bordering upon the Upper Missouri. It seemed to be particularly partial to the small valleys found, here and there, along the numerous ravines running from the interior and between the hills. Its usual demeanor is said to greatly resemble that of the common Chipping Sparrow, and, like that bird, it has a very monotonous ditty, which it seems to delight to repeat constantly, while its mate is more usefully employed in the duties of incubation. When it was approached, it would dive and conceal itself amid the low bushes around, or would seek one of the large clusters of wild roses so abundant in that section. The nest of this species is mentioned as having been usually placed on a small horizontal branch seven or eight feet from the ground, and occasionally in the broken and hollow branches of trees. These nests are also stated to have been formed of slender grasses, but in so slight a manner as, with their circular lining of horse or cattle hair, to resemble as much as possible the nest of the common socialis. The eggs were five in number, and are described as being blue with reddish-brown spots. These birds were also met with at the Great Slave Lake region by Mr. Kennicott, in the same neighborhood by B. R. Ross and J. Lockhart, and in the Red River settlements by Mr. C. A. Hubbard and Mr. Donald Gunn.

Captain Blakiston noted the arrival of this bird at Fort Carlton on the 21st of May. He speaks of its note as very peculiar, resembling, though sharper than, the buzzing made by a fly in a paper box, or a faint imitation of the sound of a watchman’s rattle. This song it utters perched on some young tree or bush, sometimes only once, at others three or four times in quick succession.

Their nests appear to have been in all instances placed in trees or in shrubs, generally in small spruces, two or three feet from the ground. In one instance it was in a clump of small bushes not more than six inches from the ground, and only a few rods from the buildings of Fort Resolution.

Both this species and the S. breweri were found by Lieutenant Couch at Tamaulipas in March, 1855. It does not appear to have been met with by any other of the exploring expeditions, but in 1864, for the first time, as Dr. Heermann states, to his knowledge, these birds were found quite plentiful near San Antonio, Texas, by Mr. Dresser. This was in April, in the fields near that town. They were associating with the Melospiza lincolni and other Sparrows. They remained about San Antonio until the middle of May, after which none were observed.

The eggs of this species are of a light blue, with a slight tinge of greenish, and are marked around the larger end with spots and blotches of a purplish-brown, rather finer, perhaps, than in the egg of S. socialis, though very similar to it. They average .70 of an inch in length, and vary in breadth from .50 to .52 of an inch.

Spizella pallida, var. breweri, CassinBREWER’S SPARROWEmberiza pallida, Aud. Orn. Biog. V, 1839, 66, pl. cccxcviii, f. 2.—Ib. Synopsis, 1839.—Ib. Birds Am. III, 1841, 71, pl. clxi (not of Swainson, 1831). Spizella breweri, Cassin, Pr. A. N. Sc. VIII, Feb. 1856, 40.—Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 475.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 209.

Sp. Char. Similar to S. pallida; the markings including the nuchal collar more obsolete; no distinct median and superciliary light stripes. The crown streaked with black. Some of the feathers on the sides with brown shafts. Length, 5 inches; wing, 2.50. Young streaked beneath, as in pallida.

Hab. Rocky Mountains of United States to the Pacific coast.

This race is very similar to the S. pallida, and requires close and critical comparison to separate it. The streaks on the back are narrower, and the central ashy and lateral whitish stripes of the crown are scarcely, if at all, appreciable. The clear unstreaked ash of the back of the neck, too, is mostly wanting. The feathers along the sides of the body, near the tibia, and occasionally elsewhere on the sides, have brownish shafts, not found in the other. The differences are perhaps those of race, rather than of species, though they are very appreciable.

Habits. This species bears a very close resemblance to the S. pallida in its external appearance, but there are certain constant differences which, with the peculiarities of their distinctive distributions and habits, seem to establish their specific separation. The present bird is found from the Pacific coast to the Rocky Mountains, and from the northern portion of California to the Rio Grande and Mexico. Dr. Kennerly found it in February, 1854, throughout New Mexico, from the Rio Grande to the Great Colorado, along the different streams, where it was feeding upon the seeds of several kinds of weeds.

Dr. Heermann, while accompanying the surveying party of Lieutenant Williamson, between the 32d. and 35th parallels, found these Sparrows throughout his entire route, both in California and in Texas. On the passage from the Pimos villages to Tucson he observed large flocks gleaning their food among the bushes as they were moving southward. In the Tejon valley, during the fall season, he was constantly meeting them associated with large flocks of other species of Sparrows, congregated around the cultivated fields of the Indians, where they find a bountiful supply of seeds. For this purpose they pass the greater part of the time upon the ground.

Dr. Woodhouse also met with this Sparrow throughout New Mexico, wherever food and water were to be found in sufficient quantity to sustain life.

In Arizona, near Fort Whipple, Dr. Coues states that this bird is a rare summer resident. He characterizes it as a shy, retiring species, keeping mostly in thick brush near the ground.

Mr. Ridgway states that he found this interesting little Sparrow, while abundant in all fertile portions, almost exclusively an inhabitant of open situations, such as fields or bushy plains, among the artemesia especially, where it is most numerous. It frequents alike the valleys and the mountains. At Sacramento it was the most abundant Sparrow, frequenting the old fields. In this respect it very much resembles the eastern Spizella pusilla, from which, however, it is in many respects very different.

The song of Brewer’s Sparrow, he adds, for sprightliness and vivacity is not excelled by any other of the North American Fringillidæ, being inferior only to that of the Chondestes grammaca in power and richness, and even excelling it in variety and compass. Its song, while possessing all the plaintiveness of tone so characteristic of the eastern Field Sparrow, unites to this quality a vivacity and variety fully equalling that of the finest Canary. This species is not resident, but arrives about the 9th of April. He found its nest and eggs in the Truckee Reservation, early in June. The nests were in sage-bushes about three feet from the ground.

Dr. Cooper found small flocks of this species at Fort Mohave, after March 20, frequenting grassy spots among the low bushes, and a month later they were singing, he adds, much like a Canary, but more faintly. They are presumed to remain in the valley all summer.

The eggs, four in number, are of a light bluish-green color, oblong in shape, more rounded at the smaller end than the eggs of the socialis, and the ground is more of a green than in those of S. pallida. They are marked and blotched in scattered markings of a golden-brown color. These blotches are larger and more conspicuous than in the eggs of the other species. They measure .70 by .51 of an inch.

Spizella atrigularis, BairdBLACK-CHINNED SPARROWSpinites atrigularis, Cabanis, Mus. Hein. 1851, 133. Spizella atrigularis, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1858, 476, pl. lv, f. 1.—Ib. Mex. Bound. II, Birds, p. 16, pl. xvii, f. 1.—Cooper, Orn. Cal. 1, 210. Struthus atrimentalis, Couch, Pr. A. N. Sc. Phil. VII, April, 1854, 67.

Sp. Char. Tail elongated, deeply forked and divaricated. General color bluish-ash, paler beneath, and turning to white on the middle of the belly. Interscapular region yellowish-rusty, streaked with black. Forehead, loral region, and side of head as far as eyes, chin, and upper part of throat black. Quills and tail-feathers very dark brown, edged with ashy. Edges of coverts like the back. No white bands on the wings. Bill red, feet dusky. Immature birds, and perhaps adult female, without any black on head. Length, 5.50; wing, 2.50; tail, 3.00.

Hab. Mexico, just south of the Rio Grande; Fort Whipple, Ariz. (Coues); Cape St. Lucas.

This species is about the size of S. pusilla and S. socialis, resembling the former most in its still longer tail. This is more deeply forked and divaricated, with broader feathers than in either. The wing is much rounded; the fourth quill longest; the first almost the shortest of the primaries.

Habits. This species is a Mexican bird, found only within the limits of the United States along the borders. But little is known as to its history. It is supposed to be neither very abundant nor to have an extended area of distribution. It was met with by Dr. Coues in the neighborhood of Fort Whipple, Arizona, where it arrives in April and leaves again in October, collecting, before its departure, in small flocks. In the spring he states that it has a very sweet and melodious song, far surpassing in power and melody the notes of any other of this genus that he has ever heard.

Dr. Coues furnishes me with the following additional information in regard to this species: “This is not a common bird at Fort Whipple, and was only observed from April to October. It unquestionably breeds in that vicinity, as I shot very young birds, in August, wanting the distinctive head-markings of the adult. A pair noticed in early April were seemingly about breeding, as the male was in full song, and showed, on dissection, highly developed sexual organs. The song is very agreeable, not in the least recalling the monotonous ditty of the Chip Bird, or the rather weak performances of some other species of the genus. In the latter part of summer and early autumn the birds were generally seen in small troops, perhaps families, in weedy places, associating with the western variety of Spizella socialis, as well as with Goldfinches.”

Lieutenant Couch met with individuals of this species at Agua Nueva, in Coahuila, Mexico, in May, 1853. They were found in small flocks among the mountains. Their nest and eggs are unknown.

Genus MELOSPIZA, BairdMelospiza, Baird, Birds N. Am. 1868, 478. (Type, Fringilla melodia, Wils.)

Melospiza melodia.

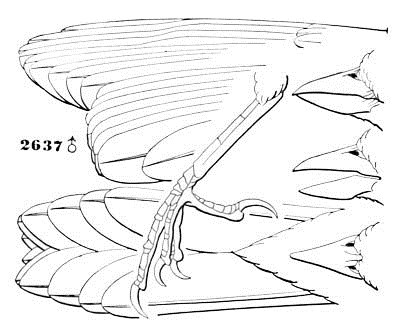

2637 ♂

Gen. Char. Body stout. Bill conical, very obsoletely notched, or smooth; somewhat compressed. Lower mandible not so deep as the upper. Commissure nearly straight. Gonys a little curved. Feet stout, not stretching beyond the tail; tarsus a little longer than the middle toe; outer toe a little longer than the inner; its claw not quite reaching to the base of the middle one. Hind toe appreciably longer than the middle one. Wings quite short and rounded, scarcely reaching beyond the base of the tail; the tertials considerably longer than the secondaries; the quills considerably graduated; the fourth longest; the first not longer than the tertials, and almost the shortest of the primaries. Tail moderately long, rather longer from coccyx than the wings, and considerably graduated; the feathers oval at the tips, and not stiffened. Crown and back similar in color, and streaked; beneath thickly streaked, except in M. palustris. Tail immaculate. Usually nest on ground; nests strongly woven of grasses and fibrous stems; eggs marked with rusty-brown and purple on a ground of a clay color.

Melospiza melodia.

This genus differs from Zonotrichia in the shorter, more graduated tail, rather longer hind toe, much more rounded wing, which is shorter; the tertiaries longer; the first quill almost the shortest, and not longer than the tertials. The under parts are spotted; the crown streaked, and like the back.

There are few species of American birds that have caused more perplexity to the ornithologist than the group of which Melospiza melodia is the type. Spread over the whole of North America, and familiar to every one, we find each region to possess a special form (to which a specific name has been given), and yet these passing into each other by such insensible gradations as to render it quite impossible to define them as species. Between M. melodia of the Atlantic States and M. insignis of Kodiak the difference seems wide; but the connecting links in the intermediate regions bridge this over so completely that, with a series of hundreds of specimens before us, we abandon the attempt at specific separation, and unite into one no less than eight species previously recognized.