Полная версия

Prohibition of Interference. Book 1

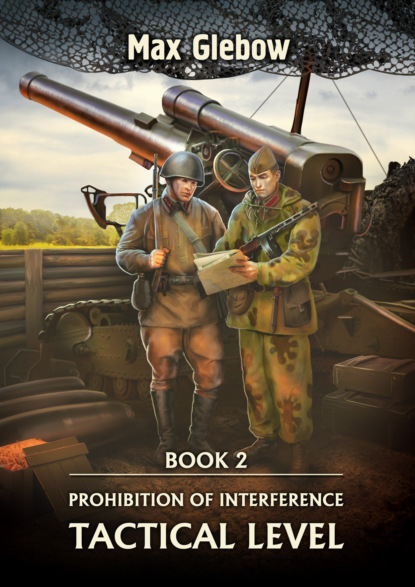

My hiding place was about 30 meters from the last car – despite the low speed, the train managed to pass quite a considerable distance, before it stopped. German planes flew in pairs over the broken train. They must have run out of bombs, but they kept shooting at the fleeing men with machine guns. Our anti-aircraft platform hadn't shown any signs of life for a minute. Through the smoke of the fire we could see the motionless barrels of Maxim machine guns looking helplessly into the sky. No one fired on the Messerschmitts, and they came at the target, as in a training exercise.

A soldier in NKVD uniform who had reached the last car shouted something, but I couldn't make it out because of the crackling of the machine guns and the roar of the fire. He tried to look inside the car, but it smelled so hot that he recoiled and took two awkward steps backward.

“Hide behind the wagon!” I yelled as I saw a string of bullet trails in the dust run along the train toward him.

The soldier heard me, but apparently did not understand what I wanted him to do. He just turned in my direction, but then a burst of machine-gun fire crossed his back, and he twitched several times and fell forward, instinctively trying to grab onto the wall of the car, but his arms, suddenly weak, slipped, and the guy slid to the ground, dropping his rifle.

Most of those who managed to jump out of the cars and didn't die in the first minutes of the bombing had already covered almost half the distance to the forest, but the enemy pilots were not going to give them a chance to get away alive. Some tried to hide in the folds of the terrain or pretend to be killed, but it did not help much. A man lying on the ground is too convenient a target for an airplane.

I didn't want to get out of my lucky hiding place at all. Here no one paid any attention to me, and the sloping earth walls provided reliable cover from the splinters. But 30 meters from my position there was a rifle, quite serviceable as it looked, and I knew that in my hands this weapon could give the men running toward the woods a few extra seconds.

Closing my eyes, I began to look at the area from above. The computer processed the image coming from orbit, filtering out the smoke, so I saw everything clearly enough. Waiting until both pairs of enemy planes were in an awkward position for an attack, I jumped out of the ravine and ran to the dead soldier, or rather, to the weapon that had fallen out of his hands.

The butt of the Mosin rifle fit comfortably in my palm. The weapon was indeed undamaged, and I considered myself very lucky, twice. I was lucky not only that the rifle was not smashed by bullets, but also that it was the weapon I had in my hands. True, it didn't have sights for shooting at high-speed, low-flying targets, but I didn't need them. But Mosin rifle had excellent accuracy by the standards of that time. The trick was that its barrel had a conical shape, tapering slightly from the breech end to the muzzle end. This resulted in additional compression of the bullet when fired and did not allow it to 'walk' in the bore.

After checking my weapon and making sure it was loaded and ready to fire, I took another look around the battlefield. The men running toward the woods needed another 30 seconds to reach cover, but both pairs of Messerschmitts, were already coming in to attack one by one.

I put the rifle to my shoulder and activated the combat mode of the sighting and navigation system. Of course, originally, it was not intended at all for shooting handguns at airplanes, but it had a lot of flexibility in settings, and in the last month and a half I had enough time to adapt my micro-implants and contact lenses to local realities.

Instead of solid smoke from a burning train, I saw clear skies with clear target marks and aiming points, that took into account the necessary deflection. The first pair of Messerschmitts was about to fly over the cars. I chose the leader, and pointed my weapon at the translucent outline of an airplane moving ahead of my target. A slight tingling sensation in my palms told me that the hand tremor suppression system had kicked in. I did the rough aiming of the rifle myself, but the bio-implants, which used my own nervous system, helped me to aim accurately. The trigger pull was long and heavy, which I knew in theory, but I still wasn't quite prepared for the fact that I had to pull the trigger so hard.

Shot! I moved the bolt handle to the left, then backward to the full, then I pushed the bolt forward and the handle to the right. Change of target… pointing… Shot!

After the fifth push to the shoulder, the magazine was empty. None of the enemy planes exploded in midair or crashed to the ground, but only the leader of the second pair fired a short and kind of tentative burst at the men running toward the woods. The rest of the planes came out of the attack without firing their machine guns. A not too thick, but clearly visible dark plume stretched behind the two Messerschmitts. All four German fighters turned smoothly to the west and quickly disappeared behind the forest.

I cancelled the combat mode of the implants, put the rifle next to its dead owner and sank tiredly to the ground. The surviving soldiers were returning from the edge of the forest to the burning train. Some helped the wounded walk, while others waddled with difficulty. I felt a stare on me and turned around. A senior lieutenant of the NKVD, commander of the security platoon of our defeated train, was looking at me silently and very attentively from the neighboring car.

Chapter 4

We spent the rest of the day helping the wounded and burying the dead. We had no means of communication, and even if we had any, it was burned up in the bombed-out cars.

There was no movement on the railroad either from Uman or from the rear, but several times German bombers and fighter planes flew close to us. We heard explosions and the rumble of artillery cannonade. The situation on the front continued to deteriorate rapidly.

We had no means of transporting the wounded. Stretchers made from cape-tents and poles cut out in the nearby woods made things a little easier, but all the same our marching unit looked like a walking hospital. There were no medics among us, so there was nothing we could do to help the wounded except for primitive bandaging.

The NKVD platoon commander, with 12 men left, tried to hold on, but the defeat of the train was an unbearable burden on him. The First Lieutenant seemed to think that he was responsible for everything that had happened.

“Comrades Red Army men, if anyone else does not know, I’m First Lieutenant Fyodorov. I am assigned to accompany your military echelon, which means I am your commander. And if that's the case, everybody listen to the battle order!” he said it in a hoarse voice as he strode in front of our uneven line, “We are now moving in a marching column to the west along the railroad tracks. We'll take turns carrying the wounded. It's evening, but we can't stay here overnight – they're waiting for us in Uman. That's where you should all get your weapons and assignments to your units. We'll walk all night if we have to. Any questions?”

I was about to ask why we, unarmed and with wounded in our arms, should go into the trap into which the outskirts of Uman were turning, but after looking into the eyes of the First lieutenant, I changed my mind. People here thought in very different terms, and no amount of reasoning could shake this officer's determination to follow orders and get us to our prescribed destination. Besides, the First Lieutenant didn't know what was really going on around us right now, and I couldn't plausibly explain to him how I knew it.

Nevertheless, our temporary commander noticed something on my face. After the fight was over, he looked in my direction regularly, but he never asked me anything until then.

“Soldier, do you have a question?” The First Lieutenant turned his whole body toward me.

“Red Armyman Nagulin,” I introduced myself and took a step out of the ranks, “Comrade First Lieutenant, we are going to the front. The situation is not quite clear, but from the looks of it, it has deteriorated a lot in recent hours. We have the rifles of your dead fighters and the machine gun platform crew. Right now your people are carrying them, but maybe it makes sense to distribute these weapons to us?”

“If we have to, we will,” the First Lieutenant answered sharply, without explaining anything, “Get the stretchers up with the wounded! We're moving out.”

“Comrade First Lieutenant…”

“Follow your orders, soldier. Or should I repeat it?” The First Lieutenant squinted unkindly, and behind his shoulder a sergeant in NKVD uniform reached for his weapon.

Well, if I have to do it, I'll do it.

“Copy that,” I answered clearly, devouring the boss with my eyes, for I had absolutely no desire to see what would happen next if I began to insist.

“That's better,” the First Lieutenant mumbled in a completely hoarse voice and went in a wide stride toward the head of the column that had begun to move. The Sergeant looked at me unkindly for a while, but then turned around and ran after the commander.

Army discipline, especially in a combat situation, is undoubtedly a wonderful thing, but I had absolutely no intention of continuing to beg for a rifle from the commander. I just wanted to tell him that walking along the railroad tracks in the direction of the train to get to Uman is a futile matter. If we do that, after 40 kilometers, which is a lot for our column, we will be at the Khristinovka station. Only from there there is a branch to Uman, which goes almost in the opposite direction, to the southeast. Uman itself is now about 25 kilometers south of us, and if you go there, it is better to go straight through fields and woods, rather than along the railroad, which not only greatly lengthens the way, but also attracts the German air force like a magnet. The latter, of course, is not so scary right now, since it's already getting dark, and enemy planes won't appear over us until morning, but the fact that once we get to Khristinovka we will still find our troops there, and not the Germans, is highly doubtful.

“Well, Pyotr, have you got it?” I didn't notice Boris next to me as I pondered, “You talk a lot, and in all the wrong places. I also like to talk, but I always know where to do it and where not to do it. This is the NKVD, you have to understand. And you started discussing orders, and in a combat situation. Did you see how that sergeant was groping the rifle? No doubt he would have fired without hesitation, at one movement of the commander's eyebrow.”

“I don't doubt it,” I didn't argue, “I could see it in his face.”

“You've gone completely feral in your taiga, I see. Stick with me, or you'll get in trouble. Be thankful that nobody whispered to the First Lieutenant or his Sergeant about how you left the wagon without permission… Apparently, they've forgotten this episode out of fear. But now it seems calmer, so maybe someone will remember, if those who saw it are alive, of course.”

“It won't be for long,” I answered softly, and immediately regretted what I had said.

“What won't be for long? Have they forgotten that not for long? That's what I'm telling you.”

“No. That's not what I mean, I mean it's calmer now, but it'll be over soon.”

“What's going to be over?”

“The silence, if you can call it that. Do you have any idea where we're going?”

“Well, to Uman, the commander told you directly.”

“We're not going to Uman! Uman is over there!” I waved my hand to the south, perpendicular to the direction of our movement, “And these tracks lead to the Khristinovka station, which is 20 kilometers west of Uman. There will be a front line there any day now, or even by tomorrow morning! Do you hear that rumbling?”

“Does the commander know less than you?” There was a suspicious mistrust in Boris's voice, “He's got a map, too! Well, he should. And how do you know where Uman is? And about Khristinovka?”

“You just had to study well in school, Boris, not dream about girls in class. My father taught me – there was no school in the taiga. You live in the great country of victorious socialism, and you should know the geography of your immense motherland. Did you remember the names of the stations we passed?”

“Well…” Boris said in a lower tone, obviously not expecting such a rebuke from me, “it seems that we passed through Talnoye… And Yurkovka.”

“Do you have any idea where we are?”

“Not really, I'm from Voronezh…”

“Have you never seen a map of the USSR either? It's only 700 kilometers from here to your Voronezh, by the way. You can get there on foot.”

“Look, Pyotr, why are you picking on me? I realized that you know geography well.”

“Well, if you understand it, then there's no need to ask stupid questions. Let's better think about how to report to the commander that this railroad won't lead us to Uman.”

“It's no use,” Boris shook his head, “He won't listen to you, and he won't listen to me either. What are you suggesting? To turn into the fields and go straight ahead? But you can lose your way easily, as there are no landmarks. And the rails are right there, you can't get lost.”

“I'll show us out,” I said without proper confidence. I understood that, but I really didn't want to go where the First Lieutenant was leading us.

“Listen to me, Pyotr…” I could hardly make out Boris's grin in the darkness, “Do you believe yourself? At night, without a road, with the wounded in our arms, in unfamiliar terrain… It's not like you can drive your finger on a map of your home country in the warmth and comfort of your own home. No offense, but it's all nonsense. After all, we have an order, and it has to be obeyed.”

Then we walked in silence, gradually getting into the rhythm, and about 30 minutes later it was our turn to carry the wounded, and there was no time to talk.

* * *No matter how hard the First Lieutenant tried to move quickly, but we still had to make three stops. The men were too exhausted for the day, and they were simply unable to endure the continuous march through the night while carrying the wounded. After the defeat of the echelon there were about 150 of us left. There were 27 wounded on stretchers, but by morning six of them had died, yet our losses did not end there. Apparently, I was not the only one who did not like the idea of walking blindly and unarmed toward the advancing Germans, and the fact that the front line was not far away could only be doubted by a deaf person.

At the last resting place just before dawn, the sergeant conducted a roll call on the orders of the commander. Our unit was 17 men short. I was beginning to understand why the First Lieutenant was so sour about my suggestion to give us the rifles of dead soldiers.

The morning greeted us unpleasantly. The indistinct roar that had sounded all night in the west had turned into a continuous rumble, in which individual violent explosions were already clearly distinguishable. But the worst thing was that it was now heard not only from the west, but also from the north and even from the northeast. It finally dawned on the First Lieutenant, too, that something wasn't going quite the way he wanted it to, despite all his unwavering determination to follow orders.

“Soldiers!” He looked at us with a frown, “Anybody here from these parts?”

The answer to the commander was silence. We were all mobilized in the eastern regions of the country. Boris, with his Voronezh, was probably the most western of us, so we couldn't please the First Lieutenant in any way. Well, almost.

“Red Army man Nagulin!” I went out of the line.

“You again?” The First Lieutenant's voice had a bad tone to it, “Are you from around here?”

“No, Comrade First Lieutenant. But I can draw a schematic map and roughly show you where we are.”

“A schematic map, then?” The commander said thoughtfully, looking at me frowningly, “Where did you come from, Red Army man Nagulin? You're newly mobilized, right? You haven't even had basic training. In fact, you should have been sent to the reserve unit first, but that's just the way it is. But you're a good shot with a rifle, I've seen it myself, and now it turns out you can read a map, and not only read a ready-made map, but draw your own. Where did you learn?”

“My father taught me. We lived almost on the border of the USSR with the Tuvan People's Republic. He was an Old Believer, he was educated in Czarist Russia, and then his grandfather finished his schooling on our farmstead. I grew up in the taiga, so I'm a good shot and I know how to handle weapons. And I've been interested in geography since childhood. I dreamed that when I grew up, I would travel and discover new lands. I know this area from the map quite well, but I have not been here myself before.”

The First Lieutenant didn't believe me, he didn't believe me at all, but nodded and took a notebook and a chemical pencil out of his field bag.

“Draw your map, Nagulin, but watch out if you lead us to the Germans…”

“Comrade Commander,” I tensed up as I drew the railroad line from Talny to Khristinovka and a little further to show the general direction to Teplik, “I, like you, don't know where the enemy is now. I'll draw a map, but it's not for me to decide where to go.”

Fyodorov only nodded silently, showing that he had heard me, and continued to watch attentively as on a sheet of his notebook the railway line leading from Khristinovka to the southeast to Uman was appearing, and as I marked these settlements.

“What about roads, rivers, bridges, woodlands?” asked the First Lieutenant when I handed him the prepared diagram.

“My memory also has its limits, Comrade Commander,” I answered, “I depicted what I remember. According to my rough guess, we are somewhere around here, about 15 kilometers from the Khristinovka station.”

“So you're saying that all night we walked the wrong way and didn't get even a meter closer to Uman?”

“That's right, Comrade Fir…”

“Silence!” bellowed Fyodorov, “Why didn't you report at once?!”

“I tried, Comrade First Lieutenant. You wouldn't listen to me.”

The First Lieutenant was silent as he continued to glare at me. He didn't have anything to say, but he seemed to really want to grind me down. Yes, I know how to make enemies, and I need to do something about it.

“Get in formation,” he finally ordered, putting my map away in his clipboard, and turned to our thinned out team, “We continue along the railroad tracks. At the nearest station we will hand over the wounded to the medics, report back to Uman, and get further instructions. Get the stretchers! Start moving!”

The situation was worse than I thought. Fyodorov did not want to admit his mistake, or maybe he just thought his actions were right. The idea of getting help at the station would have made perfect sense if it weren't for the constant rumble of the front line coming toward us.

Satellites broadcast a bleak picture from orbit. The Germans had already captured the Khristinovka station, where our commander was so eager to go. The railroad track in several places in front of us and behind us was smashed by enemy bombs. In addition to our train, two more trains were burning out on the tracks, and under the circumstances, no one was going to repair anything or remove the burnt-out cars from the tracks, nor would they have been able to do so if they wanted to. And to the north of the railroad we were rapidly encircled by the 16th motorized division of the Wehrmacht, which had almost reached Talny, and the troops defending there were clearly unable to prevent the Germans from capturing this settlement. Behind our back in the east Novoarkhangelsk was still in the hands of the Red Army, but it was already being approached from the south by the 11th German Tank Division and the SS Division Leibstandarte.

Counterattacks organized by the Southwestern Front command struck with extreme fierceness, but they crashed against the viscous defenses intelligently built by the Germans, meanwhile, the threat of a complete encirclement was already clearly looming over the 6th and 12th Soviet Armies, as well as the remnants of the Second Mechanized Corps. The battle was simmering all around us, but by some miracle our unit had not yet been directly affected, except, of course, by the destruction of the train in which we were on our way to the front.

Something had to be done urgently, otherwise our commander, who was unreservedly devoted to the cause of Lenin-Stalin but was completely inadequate, would lead us into German captivity, which was absolutely not in my plans. Except that I didn't yet understand exactly what to do.

Our luck ran out after about 15 minutes. First, a lone I-153 Seagull fighter with red stars on its wings flew almost over us to the east, which caused great excitement in our column. The plane was going low and clearly had combat damage, but I was the only one in our squadron who saw it. The rest of the soldiers waved their hands and caps, welcoming the first representative of Soviet aviation they had seen since the defeat of our train. And then I felt the familiar unpleasant itch behind my ear.

The First Lieutenant was now walking somewhere ahead, and I was just carrying a stretcher, so there was no way to get to him. But not far away from me was the Sergeant who had made it so clear to me how discussing the commander's orders in a combat situation could end up.

“Comrade Sergeant! The enemy is ahead! I hear the sound of motorcycle engines a kilometer to the left of the road behind a wooded area!”

“Column, halt!” I have to hand it to him, the Sergeant reacted seriously to my warning. He ran off to find the commander and soon the two of them were back together.

“Quiet, everybody!” The First Lieutenant commanded and listened intensely to the silence, which was very relative, for there was a good deal of rumbling all around us.

“There's nothing there!” After ten seconds, the Sergeant said, catching the commander's questioning look on his face, “I don't hear any suspicious sounds.”

Of course he couldn't hear! At this distance, the woods reliably muffled the sounds of the engines, but there was nothing else I could explain my knowledge of the approaching German motorcyclists. And they were not the only ones…

“There are at least three motorcycles and something else, heavier, but not tanks. Maybe a truck, maybe an armored personnel carrier – something is clanking there,” I reported, stubbornly looking into Fyodorov's eyes, “Over there, see? There's a road along the rails. Then it goes to the left and turns behind the forest. That's where they're coming from.”

The First Lieutenant hesitated, but action was needed immediately, and he made up his mind.

“Zhurkov, Blokhin, move forward and carefully check around the corner. The rest of you, take cover behind the embankment. Quickly! Not this side! The opposite side of the road! Sergeant Pluzhnikov!”

“That's me!”

“Keep an eye on Red Army man Nagulin!

“Copy that!”

As expected, Fyodorov's men did not make it to the road's bend. What could they, tired from the long march, do to compete with the BMW engines?

Two motorcycles with strollers jumped out from behind the woods almost simultaneously. Five seconds before Blokhin and Zhurkov heard the sound of their engines and rushed to the side of the road, simultaneously waving their hands at us. Instead of hiding behind some cover, the two NKVD fighters raised their rifles and opened fire on the Germans. It couldn't be helped – they've been taught that way, and they've learned their lesson well.

BMW motorcycle, with an MG-34 machine gun on the side trailer. Various models of such motorcycles were widely used by the Wehrmacht during World War II.

The motorcycle in front swerved to the side. The driver may have been injured, but did not lose control of his vehicle. Apparently, this was not the first time these Germans had encountered the enemy, and they were largely prepared for such a situation. In any case, the machine gun on the second motorcycle fired a long burst just five seconds after the NKVD fighters' first shot.

Blokhin fired from full height and was the first victim of return fire, catching several bullets with his chest at once. Zhurkov, apparently, had some combat experience and behaved more intelligently. He rolled into a shallow ditch and tried to shoot the motorcyclists from there, but the forces were too unequal. The soldier was simply destroyed by the fire of two machine guns.