полная версия

полная версияThe Atlantic Monthly, Volume 02, No. 10, August, 1858

Various

The Atlantic Monthly, Volume 02, No. 10, August, 1858 / A Magazine of Literature, Art, and Politics

DAPHNAIDES:

OR THE ENGLISH LAUREL, FROM CHAUCER TO TENNYSON

They in thir time did many a noble dede,And for their worthines full oft have boreThe crown of laurer leavés on the hede,As ye may in your oldé bookés rede:And how that he that was a conquerourHad by laurer alway his most honour.DAN CHAUCER: The Flowre and the Leaf.It is to be lamented that antiquarian zeal is so often diverted from subjects of real to those of merely fanciful interest. The mercurial young gentlemen who addict themselves to that exciting department of letters are open to censure as being too fitful, too prone to flit, bee-like, from flower to flower, now lighting momentarily upon an indecipherable tombstone, now perching upon a rusty morion, here dipping into crumbling palimpsests, there turning up a tattered reputation from heaps of musty biography, or discovering that the brightest names have had sad blots and blemishes scoured off by the attrition of Time's ceaseless current. We can expect little from investigators so volatile and capricious; else should we expect the topic we approach in this paper to have been long ago flooded with light as of Maedler's sun, its dust dissipated, and sundry curves and angles which still baffle scrutiny and provoke curiosity exposed even to Gallio-llke wayfarers. It is, in fact, a neglected topic. Its derivatives are obscure, its facts doubtful. Questions spring from it, sucker-like, numberless, which none may answer. Why, for instance, in apportioning his gifts among his posterity, did Phoebus assign the laurel to his step-progeny, the sons of song, and pour the rest of the vegetable world into the pharmacopoeia of the favored Æsculapius? Why was even this wretched legacy divided in aftertimes with the children of Mars? Was its efficacy as a non-conductor of lightning as reliable as was held by Tiberius, of guileless memory, Emperor of Rome? Were its leaves really found green as ever in the tomb of St. Humbert, a century and a half after the interment of that holy confessor? In what reign was the first bay-leaf, rewarding the first poet of English song, authoritatively conferred? These and other like questions are of so material concern to the matter we have in hand, that we may fairly stand amazed that they have thus far escaped the exploration of archaeologists. It is not for us to busy ourselves with other men's affairs. Time and patience shall develope profounder mysteries than these. Let us only succeed in delineating in brief monograph the outlines of a natural history of the British Laurel,–Laurea nobilis, sempervirens, florida,–and in posting here and there, as we go, a few landmarks that shall facilitate the surveys of investigators yet unborn, and this our modest enterprise shall be happily fulfilled.

One portion of it presents no serious difficulty. There is an uninterrupted canon of the Laureates running as far back as the reign of James I. Anterior, however, to that epoch, the catalogue fades away in undistinguishable darkness. Names are there of undoubted splendor, a splendor, indeed, far more glowing than that of any subsequent monarch of the bays; but the legal title to the garland falls so far short of satisfactory demonstration, as to oblige us to dismiss the first seven Laureates with a dash of that ruthless criticism with which Niebuhr, the regicide, dispatched the seven kings of Rome. To mark clearly the bounds between the mythical and the indubitable, a glance at the following brief of the Laureate fasti will greatly assist us, speeding us forward at once to the substance of our story.

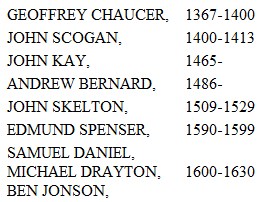

I. The MYTHICAL PERIOD, extending from the supposititious coronation of Laureate CHAUCER, in temp. Edv. III., 1367, to that of Laureate JONSON, in temp. Caroli I. To this period belong,

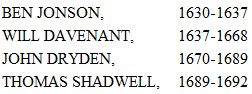

II. The DRAMATIC, extending from the latter event to the demise of Laureate SHADWELL, in temp. Gulielmi III., 1692. Here we have

III. The LYRIC, from the reign of Laureate TATE, 1693, to the demise of Laureate PYE, 1813:–

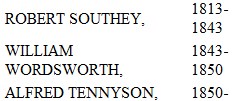

IV. The VOLUNTARY, from the accession of Laureate SOUTHEY, 1813, to the present day:–

Have no faith in those followers of vain traditions who assert the existence of the Laureate office as early as the thirteenth century, attached to the court of Henry III. Poets there were before Chaucer,–vixere fortes ante Agamemnona,–but search Rymer from cord to clasp and you shall find no documentary evidence of any one of them wearing the leaf or receiving the stipend distinctive of the place. Morbid credulity can go no farther back than to the "Father of English Poetry":–

"That renounced Poet,Dan Chaucer, well of English undefyled,On Fame's eternall beadroll worthie to be fyled":1 "Him that left half-toldThe story of Cambuscan bold;Of Camball, and of Algarsife,And who had Canace to wife":2"That noble Chaucer, in those former times,Who first enriched our English with his rhymes,And was the first of ours that ever brokeInto the Muse's treasures, and first spokeIn mighty numbers."3Tradition here first assumes that semblance of probability which rendered it current for three centuries. Edward the Third–resplendent name in the constitutional history of England–is supposed to have been so deeply impressed with Chaucer's poetical merits, as to have sought occasion for appropriate recognition. Opportunely came that high festival at the capital of the world, whereat

"Franccis Petrark, the laureat poete,… whos rethorike sweteEnlumined all Itaille of poetrie,"4received the laurel crown at the hands of the Senate of Rome, with a magnificence of ceremonial surpassed only by the triumphs of imperial victors a thousand years before. Emulous of the gorgeous example, the English monarch forthwith showered corresponding honors upon Dan Chaucer, adding the substantial perquisites of a hundred marks and a tierce of Malvoisie, a year. To this agreeable story, Laureate Warton, than whom no man was more intimately conversant with the truth there is in literary history, appears in one of his official odes to yield assent:–

"Victorious Edward gave the vernal boughOf Britain's bay to bloom on Chaucer's brow:Fired with the gift, he changed to sounds sublimeHis Norman minstrelsy's discordant chime."5The legend, however, does not bear inquiry. King Edward, in 1367, certainly granted an annuity of twenty marks to "his varlet, Geoffrey Chaucer." Seven years later there was a further grant of a pitcher of wine daily, together with the controllership of the wool and petty wine revenues for the port of London. The latter appointment, to which the pitcher of wine was doubtless incident, was attended with a requirement that the new functionary should execute all the duties of his post in person,–a requirement involving as constant and laborious occupation as that of Charles Lamb, chained to his perch in the India House. These concessions, varied slightly by subsequent patents from Richard II. and Henry IV., form the entire foundation to the tale of Chaucer's Laureateship.6 There is no reference in grant or patent to his poetical excellence or fame, no mention whatever of the laurel, no verse among the countless lines of his poetry indicating the reception of that crowning glory, no evidence that the third Edward was one whit more sensitive to the charms of the Muses than the third William, three hundred years after. Indeed, the condition with which the appointment of this illustrious custom-house officer was hedged evinced, if anything, a desire to discourage a profitless wooing of the Nine, by so confining his mind to the incessant routine of an uncongenial duty as to leave no hours of poetic idleness. Whatever laurels Fame may justly garland the temples of Dan Chaucer withal, she never, we are obliged to believe, employed royal instrument at the coronation.

John Scogan, often confounded with an anterior Henry, has been named as the Laureate of Henry IV., and immediate successor of Chaucer. Laureate Jonson seems to encourage the notion:–

"Mere Fool. Skogan? What was he?"Jophiel. Oh, a fine gentleman, and master of artsOf Henry the Fourth's time, that made disguisesFor the King's sons, and writ in ballad-royalDaintily well."Mere Fool. But he wrote like a gentleman?"Jophiel. In rhyme, fine, tinkling rhyme, and flowand verse,With now and then some sense; and he was paid for't,Regarded and rewarded; which few poetsAre nowadays."7But Warton places Scogan in the reign of Edward IV., and reduces him to the level of Court Jester, his authority being Dr. Andrew Borde, who, early in the sixteenth century, published a volume of his platitudes.8 There is nothing to prove that he was either poet or Laureate; while, on the other hand, it must be owned, one person might at the same time fill the offices of Court Poet and Court Fool. It is but fair to say that Tyrwhitt, who had all the learning and more than the accuracy of Warton, inclines to Jonson's estimate of Scogan's character and employment.

One John Kay, of whom we are singularly deficient in information, held the post of Court Poet under the amorous Edward IV. What were his functions and appointments we cannot discover.

Andrew Bernard held the office under Henry VII. and Henry VIII. He was a churchman, royal historiographer, and tutor to Prince Arthur. His official poems were in Latin. He was living as late as 1522.

John Skelton obtained the distinction of Poet-Laureate at Oxford, a title afterward confirmed to him by the University of Cambridge: mere university degrees, however, without royal indorsement. Henry VIII. made him his "Royal Orator," whatever that may have been, and otherwise treated him with favor; but we hear nothing of sack or salary, find nothing among his poems to intimate that his performances as Orator ever ran into verse, or that his "laurer" was of the regal sort.

A long stride carries us to the latter years of Queen Elizabeth, where, and in the ensuing reign of James, we find the names of Edmund Spenser, Samuel Daniel, and Michael Drayton interwoven with the bays. Spenser's possession of the laurel rests upon no better evidence than that, when he presented the earlier books of the "Faery Queen" to Elizabeth, a pension of fifty pounds a year was conferred upon him, and that the praises of Gloriana ring through his realm of Faëry in unceasing panegyric. But guineas are not laurels, though for sundry practical uses they are, perhaps, vastly better; nor are the really earnest and ardent eulogia of the bard of Mulla the same in kind with the harmonious twaddle of Tate, or the classical quiddities of Pye. He was of another sphere, the highest heaven of song, who

"Waked his lofty lay To grace Eliza's golden sway;And called to life old Uther's elfin-tale,And roved through many a necromantic vale, Portraying chiefs who knew to tame The goblin's ire, the dragon's flame, To pierce the dark, enchanted hall Where Virtue sat in lonely thrall. From fabling Fancy's inmost store A rich, romantic robe he bore,A veil with visionary trappings hung,And o'er his Virgin Queen the fairy-texture flung."9Samuel Daniel was not only a favorite of Queen Elizabeth, but more decidedly so of her successor in the queendom, Anne of Denmark. In the household of the latter he held the position of Groom of the Chamber, a sinecure of handsome endowment, so handsome, indeed, as to warrant an occasional draft upon his talents for the entertainment of her Majesty's immediate circle, which held itself as far as possible aloof from the court, and was disposed to be self-reliant for its amusements. Daniel had entered upon the vocation of courtier with flattering auspices. His precocity while at Oxford has found him a place in the "Bibliotheca Eruditorum Præcocium." Anthony Wood bears witness to his thorough accomplishments in all kinds, especially in history and poetry, specimens of which, the antiquary tells us, were still, in his time, treasured among the archives of Magdalen. He deported himself so amiably in society, and so inoffensively among his fellow-bards, and versified his way so tranquilly into the good graces of his royal mistresses, distending the thread, and diluting the sense, and sparing the ornaments, of his passionless poetry,–if poetry, which, by the definition of its highest authority, is "simple, sensuous, passionate," can ever be unimpassioned,–that he was the oracle of feminine taste while he lived, and at his death bequeathed a fame yet dear to the school of Southey and Wordsworth. Daniel was no otherwise Laureate than his position in the queen's household may authorize that title. If ever so entitled by contemporaries, it was quite in a Pickwickian and complimentary sense. His retreat from the busy vanity of court life, an event which happened several years before his decease in 1619, was hastened by the consciousness of a waning reputation, and of the propriety of seeking better shelter than that of his laurels. His eloquent "Defense of Rhyme" still asserts for him a place in the hearts of all lovers of stately English prose.

Old Michael Drayton, whose portrait has descended to us, surmounted with an exuberant twig of bays, is vulgarly classed with the legitimate Laureates. Southey, pardonably anxious to magnify an office belittled by some of its occupants, does not scruple to rank Spenser, Daniel, and Drayton among the Laurelled:–

"That wreath, which, in Eliza's golden days, My master dear, divinest Spenser, wore,That which rewarded Drayton's learned lays, Which thoughtful Ben and gentle Daniel bore," etc.But in sober prose Southey knew, and later in life taught, that not one of the three named ever wore the authentic laurel.10 That Drayton deserved it, even as a successor of the divinest Spenser, who shall deny? With enough of patience and pedantry to prompt the composition of that most laborious, and, upon the whole, most humdrum and wearisome poem of modern times, the "Polyolbion," he nevertheless possessed an abounding exuberance of delicate fancy and sound poetical judgment, traces of which flash not unfrequently even athwart the dulness of his magnum opus, and through the mock-heroism of "England's Heroical Epistles," while they have full play in his "Court of Faëry." Drayton's great defect was the entire absence of that dramatic talent so marvellously developed among his contemporaries,–a defect, as we shall presently see, sufficient of itself to disqualify him for the duties of Court Poet. But, what was still worse, his mind was not gifted with facility and versatility of invention, two equally essential requisites; and to install him in a position where such faculties were hourly called into play would have been to put the wrong man in the worst possible place. Drayton was accordingly a court-pensioner, but not a court-poet. His laurel was the honorary tribute of admiring friends, in an age when royal pedantry rendered learning fashionable and a topic of exaggerated regard. Southey's admission is to this purpose. "He was," he says, "one of the poets to whom the title of Laureate was given in that age,–not as holding the office, but as a mark of honor, to which they were entitled." And with the poetical topographer such honors abounded. Not only was he gratified with the zealous labors of Selden in illustration of the "Polyolbion," but his death was lamented in verse of Jonson, upon marble supplied by the Countess of Dorset:–

"Do, pious marble, let thy readers knowWhat they and what their children oweTo Drayton's name, whose sacred dustWe recommend unto thy trust.Protect his memory, and preserve his story;Remain a lasting monument of his glory:And when thy ruins shall disclaimTo be the treasurer of his name,His name, that cannot fade, shall beAn everlasting monument to thee."The Laureateship, we thus discover, had not, down to the days of James, become an institution. Our mythical series shrink from close scrutiny. But in the gayeties of the court of the Stuarts arose occasion for the continuous and profitable employment of a court-poet, and there was enough thrift in the king to see the advantage of securing the service for a certain small annuity, rather than by the payment of large sums as presents for occasional labors. The masque, a form of dramatic representation, borrowed from the Italian, had been introduced into England during the reign of Elizabeth. The interest depended upon the development of an allegorical subject apposite to the event which the performance proposed to celebrate, such as a royal marriage, or birthday, or visit, or progress, or a marriage or other notable event among the nobility and gentry attached to the court, or an entertainment in honor of some distinguished personage. To produce startling and telling stage effects, machinery of the most ingenious contrivance was devised; scenery, as yet unknown in ordinary exhibitions of the stage, was painted with elaborate finish; goddesses in the most attenuated Cyprus lawn, bespangled with jewels, had to slide down upon invisible wires from a visible Olympus; Tritons had to rise from the halls of Neptune through waters whose undulations the nicer resources of recent art could not render more genuinely marine; fountains disclosed the most bewitching of Naiads; and Druidical oaks, expanding, surrendered the imprisoned Hamadryad to the air of heaven. Fairies and Elves, Satyrs and Forsters, Centaurs and Lapithae, played their parts in these gaudy spectacles with every conventional requirement of shape, costume, and behavior point-de-vice, and were supplied by the poet, to whom the letter-press of the show had been confided, with language and a plot, both pregnant with more than Platonic morality. Some idea of the magnificence of these displays, which beggared the royal privy-purse, drove household-treasurers mad, and often left poet and machinist whistling for pay, may be gathered from the fact that a masque sometimes cost as much as two thousand pounds in the mechanical getting-up, a sum far more formidable in the days of exclusively hard money than in these of paper currency. Scott has described, for the benefit of the general reader, one such pageant among the "princely pleasures of Kenilworth"; while Milton, in his "Masque performed at Ludlow Castle," presents the libretto of another, of the simpler and less expensive sort. During the reign of James, the passion for masques kindled into a mania. The days and nights of Inigo Jones were spent in inventing machinery and contriving stage-effects. Daniel, Middleton, Fletcher, and Jonson were busied with the composition of the text; and the court ladies and cavaliers were all from morning till night in the hands of their dancing and music masters, or at private study, or at rehearsal, preparing for the pageant, the representation of which fell to their share and won them enviable applause. Of course the burden of original invention fell upon the poets; and of the poets, Daniel and Jonson were the most heavily taxed. In 1616, James I., by patent, granted to Jonson an annuity for life of one hundred marks, to him in hand not often well and truly paid. He was not distinctly named as Laureate, but seems to have been considered such; for Daniel, on his appointment, "withdrew himself," according to Gifford, "entirely from court." The strong-boxes of James and Charles seldom overflowed. Sir Robert Pye, an ancestor of that Laureate Pye whom we shall discuss by-and-by, was the paymaster, and often and again was the overwrought poet obliged to raise

"A woful cryTo Sir Robert Pye,"before some small instalment of long arrearages could be procured. And when, rarely, very rarely, his Majesty condescended to remember the necessities of "his and the Muses' servant," and send a present to the Laureate's lodgings, its proportions were always so small as to excite the ire of the insulted Ben, who would growl forth to the messenger, "He would not have sent me this, (scil. wretched pittance,) did I not live in an alley."

We now arrive at the true era of the Laureateship. Charles, in 1630, became ambitious to signalize his reign by some fitting tribute to literature. A petition from Ben Jonson pointed out the way. The Laureate office was made a patentable one, in the gift of the Lord Chamberlain, as purveyor of the royal amusements. Ben was confirmed in the office. The salary was raised from one hundred marks to one hundred pounds, an advance of fifty per cent, to which was added yearly a tierce of Canary wine,–an appendage appropriate to the poet's convivial habits, and doubtless suggested by the mistaken precedent of Chaucer's daily flagon of wine. Ben Jonson was certainly, of all men living in 1630, the right person to receive this honor, which then implied, what it afterward ceased to do, the primacy of the diocese of letters. His learning supplied ballast enough to keep the lighter bulk of the poet in good trim, while it won that measure of respect which mere poetical gifts and graces would not have secured. He was the dean of that group of "poets, poetaccios, poetasters, and poetillos,"11 who beset the court. If a display of erudition were demanded, Ben was ready with the heavy artillery of the unities, and all the laws of Aristotle and Horace, Quintilian and Priscian, exemplified in tragedies of canonical structure, and comedies whose prim regularity could not extinguish the most delightful and original humor–Robert Burton's excepted–that illustrated that brilliant period. But if the graceful lyric or glittering masque were called for, the boundless wealth of Ben's genius was most strikingly displayed. It has been the fashion, set by such presumptuous blunderers as Warburton and such formal prigs as Gifford, to deny our Laureate the possession of those ethereal attributes of invention and fancy which play about the creations of Shakspeare, and constitute their exquisite charm. This arbitrary comparison of Jonson and Shakspeare has, in fact, been the bane of the former's reputation. Those who have never read the masques argue, that, as "very little Latin and less Greek," in truth no learning of any traceable description, went to the creation of Ariel and Caliban, Oberon and Puck, the possession of Latin, Greek, and learning generally, incapacitates the proprietor for the same happy exercise of the finer and more gracious faculties of wit and fancy. Of this nonsense Jonson's masques are the best refutation. Marvels of ingenuity in plot and construction, they abound in "dainty invention," animated dialogue, and some of the finest lyric passages to be found in dramatic literature. They are the Laureate's true laurels. Had he left nothing else, the "rare arch-poet" would have held, by virtue of these alone, the elevated rank which his contemporaries, and our own, freely assign him. Lamb, whose appreciation of the old dramatists was extremely acute, remarks,–"A thousand beautiful passages from his 'New Inn,' and from those numerous court masques and entertainments which he was in the daily habit of furnishing, might be adduced to show the poetical fancy and elegance of mind of the supposed rugged old bard."12 And in excess of admiration at one of the Laureate's most successful pageants, Herrick breaks forth,–

"Thou hadst the wreath before, now take the tree,That henceforth none be laurel-crowned but thee."13An aspiration fortunately unrealized.

It was not long before the death of Ben, that John Suckling, one of his boon companions

"At those lyric feasts,Made at 'The Sun,''The Dog,' 'The Triple Tun,'Where they such clusters hadAs made them nobly wild, not mad,"14handed about among the courtiers his "Session of the Poets," where an imaginary contest for the laurel presented an opportunity for characterizing the wits of the day in a series of capital strokes, as remarkable for justice as shrewd wit. Jonson is thus introduced:–