полная версия

полная версияBritain at Bay

The Norfolk Commission gave expression to two different views without attempting to reconcile them. On the one hand it laid down the main lines along which the improvement of the militia and volunteers was to be sought, and on the other hand it pointed out the advantages of the principle that it is the citizen's duty to be trained as a soldier and to fight in case of need. To go beyond this and to attempt either to reconcile the two currents of thought or to decide between them, was impossible for a Commission appointed to deal with only a fraction of the problem of national defence. The two sets of views, however, continue to exist side by side, and the nation yet has to do what the Norfolk Commission by its nature was debarred from doing. The Government, represented in this matter by Mr. Haldane, is still in the position of relying upon an improved militia and volunteer force. The National Service League, on the other hand, advocates the principle of the citizen's duty, though it couples with it a specific programme borrowed from the Swiss system, the adoption of which was deprecated in the Commission's Report. The public is somewhat puzzled by the appearance of opposition between what are thought of as two schools, and indeed Mr. Haldane in his speech introducing the Army Estimates on March 4, 1909, described the territorial force as a safeguard against universal service.

The time has perhaps come when the attempt should be made to find a point of view from which the two schools of thought can be seen in due perspective, and from which, therefore, a definite solution of the military problem may be reached.

By what principle must our choice between the two systems be determined? By the purpose in hand. The sole ultimate use of an army is to win the nation's battles, and if one system promises to fulfil that purpose while the other system does not, we cannot hesitate.

Great Britain requires an army as one of the instruments of success in a modern British war, and we have therefore to ascertain, in general, the nature of a modern war, and in particular the character of such wars as Great Britain may have to wage.

The distinguishing feature of the conflict between two modern great States is that it is a struggle for existence, or, at any rate, a wrestle to a fall. The mark of the modern State is that it is identified with the population which it comprises, and to such a State the name "nation" properly belongs. The French Revolution nationalised the State and in consequence nationalised war, and every modern continental State has so organized itself with a view to war that its army is equivalent to the nation in arms.

The peculiar character of a British war is due to the insular character of the British State. A conflict with a great continental Power must begin with a naval struggle, which will be carried on with the utmost energy until one side or the other has established its predominance on the sea. If in this struggle the British navy is successful, the effect which can be produced on a continental State by the victorious navy will not be sufficient to cause the enemy to accept peace upon British conditions. For that purpose, it will be necessary to invade the enemy's territory and to put upon him the constraint of military defeat, and Great Britain therefore requires an army strong enough either to effect this operation or to encourage continental allies to join with it in making the attempt.

In any British war, therefore, which is to be waged with prospect of success, Great Britain's battles must be fought and won on the enemy's territory and against an army raised and maintained on the modern national principle.

This is the decisive consideration affecting British military policy.

In case of the defeat of the British navy a continental enemy would, undoubtedly, attempt the invasion and at least the temporary conquest of Great Britain. The army required to defeat him in the United Kingdom would need to have the same strength and the same qualities as would be required to defeat him in his own territory, though, if the invasion had been preceded by naval defeat, it is very doubtful whether any military success in the United Kingdom would enable Great Britain to continue her resistance with much hope of ultimate success.

For these reasons I cannot believe that Great Britain's needs are met by the possession of any force the employment of which is, by the conditions of its service, limited to fighting in the United Kingdom. A British army, to be of any use, must be ready to go and win its country's battles in the theatre of war in which its country requires victories. That theatre of war will never be the United Kingdom unless and until the navy has failed to perform its task, in which case it will probably be too late to win battles in time to avert the national overthrow which must be the enemy's aim.

There are, however, certain subsidiary services for which any British military system must make provision.

These are:—

(1) Sufficient garrisons must be maintained during peace in India, in Egypt, for some time to come in South Africa, and in certain naval stations beyond the seas, viz., Gibraltar, Malta, Ceylon, Hong Kong, Singapore, Mauritius, West Africa, Bermuda, and Jamaica. It is generally agreed that the principle of compulsory service cannot be applied for the maintenance of these garrisons, which must be composed of professional paid soldiers.

(2) Experience shows that a widespread Empire, like the British, requires from time to time expeditions for the maintenance of order on its borders against half civilised or savage tribes. This function was described in an essay on "Imperial Defence," published by Sir Charles Dilke and the present writer in 1892 as "Imperial Police."

It would not be fair, for the purpose of one of these small expeditions, arbitrarily to call upon a fraction of a force maintained on the principle of compulsion. Accordingly any system must provide a special paid reserve for the purpose of furnishing the men required for such an expedition.

An army able to strike a serious blow against a continental enemy in his own territory would evidently be equally able to defeat an invading army if the necessity should arise. Accordingly the military question for Great Britain resolves itself into the provision of an army able to carry on serious operations against a European enemy, together with the maintenance of such professional forces as are indispensable for the garrisons of India, Egypt, and the over-sea stations enumerated above and for small wars.

XVI

TWO SYSTEMS CONTRASTED

I proceed to describe a typical army of the national kind, and to show how the system of such an army could be applied in the case of Great Britain.

The system of universal service has been established longer in Germany than in any other State, and can best be explained by an account of its working in that country. In Germany every man becomes liable to military service on his seventeenth birthday, and remains liable until he is turned forty-five. The German army, therefore, theoretically includes all German citizens between the ages of seventeen and forty-five, but the liability is not enforced before the age of twenty nor after the age of thirty-nine, except in case of some supreme emergency. Young men under twenty, and men between thirty-nine and forty-five, belong to the Landsturm. They are subjected to no training, and would not be called upon to fight except in the last extremity. Every year all the young men who have reached their twentieth birthday are mustered and classified. Those who are not found strong enough for military service are divided into three grades, of which one is dismissed as unfit; a second is excused from training and enrolled in the Landsturm; while a third, whose physical defects are minor and perhaps temporary, is told off to a supplementary reserve, of which some members receive a short training. Of those selected as fit for service a few thousand are told off to the navy, the remainder pass into the army and join the colours.

The soldiers thus obtained serve in the ranks of the army for two years if assigned to the infantry, field artillery, or engineers, and for three years if assigned to the cavalry or horse artillery. At the expiration of the two or three years they pass into the reserve of the standing army, in which they remain until the age of twenty-seven, that is, for five years in the case of the infantry and engineers, and for four years in the case of the cavalry and horse artillery. At twenty-seven all alike cease to belong to the standing army, and pass into the Landwehr, to which they continue to belong to the age of thirty-nine. The necessity to serve for at least two years with the colours is modified in the case of young men who have reached a certain standard of education, and who engage to clothe, feed, equip, and in the mounted arms to mount themselves. These men are called "one year volunteers," and are allowed to pass into the reserve of the standing army at the expiration of one year with the colours.

In the year 1906, 511,000 young men were mustered, and of these 275,000 were passed into the standing army, 55,000 of them being one year volunteers. The men in any year so passed into the army form an annual class, and the standing army at any time is made up, in the infantry, of two annual classes, and in the cavalry and horse artillery of three annual classes. In case of war, the army of first line would be made up by adding to the two or three annual classes already with the colours the four or five annual classes forming the reserve, that is, altogether seven annual classes. Each of these classes would number, when it first passed into the army, about 275,000; but as each class must lose every year a certain number of men by death, by diseases which cause physical incapacity from service, and by emigration, the total army of first line must fall short of the total of seven times 275,000. It may probably be taken at a million and a half. In the second line come the twelve annual classes of Landwehr, which will together furnish about the same numbers as the standing army.

Behind the Landwehr comes the supplementary reserve, and behind that again the Landsturm, comprising the men who have been trained and are between the ages of thirty-nine and forty-five, the young men under twenty, and all those who, from physical weakness, have been entirely exempted from training.

During their two or three years with the colours the men receive an allowance or pay of twopence halfpenny a day. Their service is not a contract but a public duty, and while performing it they are clothed, lodged, and fed by the State. When passed into the reserve they resume their normal civil occupation, except that for a year or two they are called up for a few weeks' training and manoeuvres during the autumn.

In this way all German citizens, so far as they are physically fit, with a few exceptions, such as the only son and support of a widow, receive a thorough training as soldiers, and Germany relies in case of war entirely and only upon her citizens thus turned into soldiers.

The training is carried out by officers and non-commissioned officers, who together are the military schoolmasters of the nation, and, like other proficient schoolmasters, are paid for their services by which they live. Broadly speaking, there are in Germany no professional soldiers except the officers and non-commissioned officers, from whom a high standard of capacity as instructors and trainers during peace and as leaders in war is demanded and obtained.

The high degree of military proficiency which the German army has acquired is due to the excellence of the training given by the officers and to the thoroughness with which, during a course of two or three years, that training can be imparted. The great numbers which can be put into the field are due to the practice of passing the whole male population, so far as it is physically qualified, through this training, so that the army in war represents the whole of the best manhood of the country between the ages of twenty and forty.

The total of three millions which has been given above is that which was mentioned by Prince Bismarck in a speech to the Reichstag in 1887. The increase of population since that date has considerably augmented the figures for the present time, and the corresponding total to-day slightly exceeds four millions.

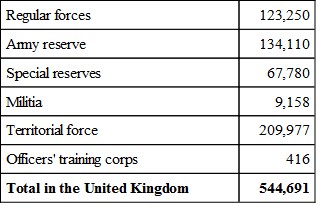

The results of the British system are shown in the following table, which gives, from the Army Estimates, the numbers of the various constituents of the British army on the 1st of January 1909. There were at that date in the United Kingdom:—

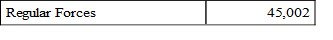

In Egypt and the Colonies:—

he British troops in India are paid for by the Indian Government and do not appear in the British Army Estimates. Of the force maintained in the United Kingdom, it will be observed that it falls, roughly, into three categories.

In the first place come the first-rate troops which may be presumed to have had a thorough training for war. This class embraces only the regulars and the army reserve, which together slightly exceed a quarter of a million. In the second class come the 68,000 of the special reserve, which, in so far as they have enjoyed the six months' training laid down in the recent reorganisation, could on a sanguine estimate be classified as second-class troops, though in view of the fact that their officers are not professional and are for the most part very slightly trained, that classification would be exceedingly sanguine. Next comes the territorial force with a maximum annual training of a fortnight in camp, preceded by ten to twenty lessons and officered by men whose professional training, though it far exceeds that of the rank and file, falls yet very much short of that given to the professional officers of a first-rate continental army. The territorial force, by its constitution, is not available to fight England's battles except in the United Kingdom, where they can never be fought except in the event of a defeat of the navy.

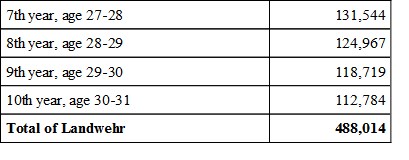

This heterogeneous tripartite army is exceedingly expensive, its cost during the current year being, according to the Estimates, very little less than 29 millions, the cost of the personnel being 23-1/2 millions, that of materièl being 4 millions, and that of administration 1-1/2 millions.

The British regular army cannot multiply soldiers as does the German army. It receives about 37,000 recruits a year. But it sends away to India and the Colonies about 23,000 each year and seldom receives them back before their eight years' colour service are over, when they pass into the first-class reserve. There pass into the reserve about 24,000 men a year, and as the normal term of reserve service is four years, its normal strength is about 96,000 men.

As the regular army contains only professional soldiers, who look, at any rate for a period of eight years, to soldiering as a living, and are prepared for six or seven years abroad, there is a limit to the supply of recruits, who are usually under nineteen years of age, and to whom the pay of a shilling a day is an attraction. Older men with prospects of regular work expect wages much higher than that, and therefore do not enlist except when in difficulties.

XVII

A NATIONAL ARMY

I propose to show that a well-trained homogeneous army of great numerical strength can be obtained on the principle of universal service at no greater cost than the present mixed force. The essentials of a scheme, based upon training the best manhood of the nation, are: first, that to be trained is a matter of duty not of pay; secondly, that every trained man is bound, as a matter of duty, to serve with the army in a national war; thirdly, that the training must be long enough to be thorough, but no longer; fourthly, that the instructors shall be the best possible, which implies that they must be paid professional officers and non-commissioned officers.

I take the age at which the training should begin at the end of the twentieth year, in order that, in case of war, the men in the ranks may be the equals in strength and endurance of the men in the ranks of any opposing army. The number of men who reach the age of twenty every year in the United Kingdom exceeds 400,000. Continental experience shows that less than half of these would be rejected as not strong enough. The annual class would therefore be about 200,000.

The principle of duty applies of course to the navy as well as to the army, and any man going to the navy will be exempt from army training. But it is doubtful whether the navy can be effectively manned on a system of very short service such as is inevitable for a national army. The present personnel of the navy is maintained by so small a yearly contingent of recruits that it will be covered by the excess of the annual class over the figure here assumed of 200,000. The actual number of men reaching the age of twenty is more than 400,000, and the probable number out of 400,000 who will be physically fit for service is at least 213,000.

I assume that for the infantry and field artillery a year's training would, with good instruction, be sufficient, and that even better and more lasting results would be produced if the last two months of the year were replaced by a fortnight of field manoeuvres in each of the four summers following the first year. For the cavalry and horse artillery I believe that the training should be prolonged for a second year.

The liability to rejoin the colours, in case of a national war, should continue to the end of the 27th year, and be followed by a period of liability in the second line, Landwehr or Territorial Army.

The first thing to be observed is the numerical strength of the army thus raised and trained.

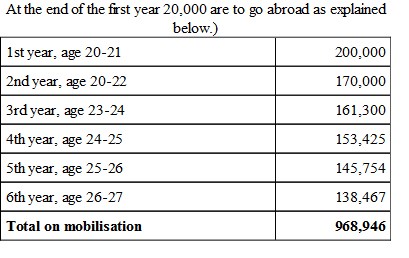

If we assume that any body of men loses each year, from death, disablement, and emigration, five per cent. of its number, the annual classes would be as follows:—

This gives an army of close upon a million men in first line in addition to the British forces in India, Egypt, and the colonial stations.

If from the age of 27 to that of 31 the men were in the Landwehr, that force would be composed of four annual classes as follows:—

There is no need to consider the further strength that would be available if the liability were prolonged to the age of 39, as it is in Germany.

The liability thus enforced upon all men of sound physique is to fight in a national war, a conflict involving for England a struggle for existence. But that does not and ought not to involve serving in the garrison of Egypt or of India during peace, nor being called upon to take part in one of the small wars waged for the purpose of policing the Empire or its borders. These functions must be performed by professional, i.e. paid soldiers.

The British army has 76,000 men in India and 45,000 in Egypt, South Africa, and certain colonial stations. These forces are maintained by drafts from the regular army at home, the drafts amounting in 1908 to 12,000 for India and 11,000 for the Colonies.

Out of every annual class of 200,000 young men there will be a number who, after a year's training, will find soldiering to their taste, and will wish to continue it. These should be given the option of engaging for a term of eight years in the British forces in India, Egypt, or the Colonies. There they would receive pay and have prospects of promotion to be non-commissioned officers, sergeants, warrant officers or commissioned officers, and of renewing their engagement if they wished either for service abroad or as instructors in the army at home. These men would leave for India, Egypt, or a colony at the end of their first year. I assume that 20,000 would be required, because eight annual classes of that strength, diminishing at the rate of five per cent. per annum, give a total of 122,545, and the eight annual classes would therefore suffice to maintain the 121,000 now in India, Egypt, and the Colonies. Provision is thus made for the maintenance of the forces in India, Egypt, and the Colonies.

There must also be provision for the small wars to which the Empire is liable. This would be made by engaging every year 20,000 who had finished their first year's training to serve for pay, say 1s. a day, for a period say of six months, of the second year, and afterwards to join for five years the present first-class reserve at 6d. a day, with liability for small wars and expeditions. At the end of the five years these men would merge in the general unpaid reserve of the army. They might during their second year's training be formed into a special corps devoting most of the time to field manoeuvres, in which supplementary or reserve officers could receive special instruction.

It would be necessary also to keep with the colours for some months after the first year's training a number of garrison artillery and engineers to provide for the security of fortresses during the period between the time of sending home one annual class and the preliminary lessons of the next. These men would be paid. I allow 10,000 men for this purpose, and these, with the 20,000 prolonging their training for the paid reserve, and with the mounted troops undergoing the second year's training, would give during the winter months a garrison strength at home of 50,000 men.

The mobilised army of a million men would require a great number of extra officers, who should be men of the type of volunteer officers selected for good education and specially trained, after their first year's service, in order to qualify them as officers. Similar provision must be made for supplementary non-commissioned officers.

XVIII

THE COST

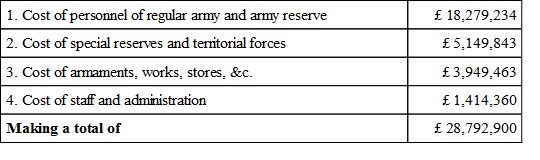

It will probably be admitted that an army raised and trained on the plan here set forth would be far superior in war to the heterogeneous body which figures in the Army Estimates at a total strength of 540,000 regulars, militia, and volunteers. Its cost would in no case be more than that of the existing forces, and would probably be considerably less. This is the point which requires to be proved.

The 17th Appendix to the Army Estimates is a statement of the cost of the British army, arranged under the four headings of:—

In the above table nearly a million is set down for the cost of certain labour establishments and of certain instructional establishments, which may for the present purpose be neglected. Leaving them out, the present cost of the personnel of the Regular Army, apart from staff, is, £15,942,802. For this cost are maintained officers, non-commissioned officers and men, numbering altogether 170,000.

The lowest pay given is that of 1s. a day to infantry privates, the privates of the other arms receiving somewhat higher and the non-commissioned officers very much higher rates of pay.

If compulsory service were introduced into Great Britain, pay would become unnecessary for the private soldier; but he ought to be and would be given a daily allowance of pocket-money, which probably ought not to exceed fourpence. The mounted troops would be paid at the rate of 1s. a day during their second year's service.

Assuming then that the private soldier received fourpence a day instead of 1s. a day, and that the officers and non-commissioned officers were paid as at present, the cost of the army would be reduced by an amount corresponding to 8d. a day for 148,980 privates. That amount is £1,812,590, the deduction of which would reduce the total cost to £14,137,212. At the same rate…

This is slightly in excess of the present cost of the personnel of the Army, but, whereas the present charge only provides for the heterogeneous force already described of 589,000 men, the charges here explained provide for a short-service homogeneous army of one million and a half, as well as for the 45,000 troops permanently maintained in Egypt and the Colonies.