полная версия

полная версияMornings in Florence

The order of these subjects, chosen by the Dominican monks themselves, was sufficiently comprehensive to leave boundless room for the invention of the painter. The execution of it was first intrusted to Taddeo Gaddi, the best architectural master of Giotto's school, who painted the four quarters of the roof entirely, but with no great brilliancy of invention, and was beginning to go down one of the sides, when, luckily, a man of stronger brain, his friend, came from Siena. Taddeo thankfully yielded the room to him; he joined his own work to that of his less able friend in an exquisitely pretty and complimentary way; throwing his own greater strength into it, not competitively, but gradually and helpfully. When, however, he had once got himself well joined, and softly, to the more simple work, he put his own force on with a will and produced the most noble piece of pictorial philosophy19 and divinity existing in Italy.

This pretty, and, according to all evidence by me attainable, entirely true, tradition has been all but lost, among the ruins of fair old Florence, by the industry of modern mason-critics—who, without exception, labouring under the primal (and necessarily unconscious) disadvantage of not knowing good work from bad, and never, therefore, knowing a man by his hand or his thoughts, would be in any case sorrowfully at the mercy of mistakes in a document; but are tenfold more deceived by their own vanity, and delight in overthrowing a received idea, if they can.

Farther: as every fresco of this early date has been retouched again and again, and often painted half over,—and as, if there has been the least care or respect for the old work in the restorer, he will now and then follow the old lines and match the old colours carefully in some places, while he puts in clearly recognizable work of his own in others,—two critics, of whom one knows the first man's work well, and the other the last's, will contradict each other to almost any extent on the securest grounds. And there is then no safe refuge for an uninitiated person but in the old tradition, which, if not literally true, is founded assuredly on some root of fact which you are likely to get at, if ever, through it only. So that my general directions to all young people going to Florence or Rome would be very short: "Know your first volume of Vasari, and your two first books of Livy; look about you, and don't talk, nor listen to talking."

On those terms, you may know, entering this chapel, that in Michael Angelo's time, all Florence attributed these frescos to Taddeo Gaddi and Simon Memmi.

I have studied neither of these artists myself with any speciality of care, and cannot tell you positively, anything about them or their works. But I know good work from bad, as a cobbler knows leather, and I can tell you positively the quality of these frescos, and their relation to contemporary panel pictures; whether authentically ascribed to Gaddi, Memmi, or any one else, it is for the Florentine Academy to decide.

The roof, and the north side, down to the feet of the horizontal line of sitting figures, were originally third-rate work of the school of Giotto; the rest of the chapel was originally, and most of it is still, magnificent work of the school of Siena. The roof and north side have been heavily repainted in, many places; the rest is faded and injured, but not destroyed in its most essential qualities. And now, farther, you must bear with just a little bit of tormenting history of painters.

There were two Gaddis, father and son,—Taddeo and Angelo. And there were two Memmis, brothers,—Simon and Philip.

I daresay you will find, in the modern books, that Simon's real name was Peter, and Philip's real name was Bartholomew; and Angelo's real name was Taddeo, and Taddeo's real name was Angelo; and Memmi's real name was Gaddi, and Gaddi's real name was Memmi. You may find out all that at your leisure, afterwards, if you like. What it is important for you to know here, in the Spanish Chapel, is only this much that follows:—There were certainly two persons once called Gaddi, both rather stupid in religious matters and high art; but one of them, I don't know or care which, a true decorative painter of the most exquisite skill, a perfect architect, an amiable person, and a great lover of pretty domestic life. Vasari says this was the father, Taddeo. He built the Ponte Vecchio; and the old stones of it—which if you ever look at anything on the Ponte Vecchio but the shops, you may still see (above those wooden pent-houses) with the Florentine shield—were so laid by him that they are unshaken to this day.

He painted an exquisite series of frescos at Assisi from the Life of Christ; in which,—just to show you what the man's nature is,—when the Madonna has given Christ into Simeon's arms, she can't help holding out her own arms to him, and saying, (visibly,) "Won't you come back to mamma?" The child laughs his answer—"I love you, mamma; but I'm quite happy just now."

Well; he, or he and his son together, painted these four quarters of the roof of the Spanish Chapel. They were very probably much retouched afterwards by Antonio Veneziano, or whomsoever Messrs. Crowe and Cavalcasella please; but that architecture in the descent of the Holy Ghost is by the man who painted the north transept of Assisi, and there need be no more talk about the matter,—for you never catch a restorer doing his old architecture right again. And farther, the ornamentation of the vaulting ribs is by the man who painted the Entombment, No. 31 in the Galerie des Grands Tableaux, in the catalogue of the Academy for 1874. Whether that picture is Taddeo Gaddi's or not, as stated in the catalogue, I do not know; but I know the vaulting ribs of the Spanish Chapel are painted by the same hand.

Again: of the two brothers Memmi, one or other, I don't know or care which, had an ugly way of turning the eyes of his figures up and their mouths down; of which you may see an entirely disgusting example in the four saints attributed to Filippo Memmi on the cross wall of the north (called always in Murray's guide the south, because he didn't notice the way the church was built) transept of Assisi. You may, however, also see the way the mouth goes down in the much repainted, but still characteristic No. 9 in the Uffizii.20

Now I catch the wring and verjuice of this brother again and again, among the minor heads of the lower frescoes in this Spanish Chapel. The head of the Queen beneath Noah, in the Limbo,—(see below) is unmistakable.

Farther: one of the two brothers, I don't care which, had a way of painting leaves; of which you may see a notable example in the rod in the hand of Gabriel in that same picture of the Annunciation in the Uffizii. No Florentine painter, or any other, ever painted leaves as well as that, till you get down to Sandro Botticelli, who did them much better. But the man who painted that rod in the hand of Gabriel, painted the rod in the right hand of Logic in the Spanish Chapel,—and nobody else in Florence, or the world, could.

Farther (and this is the last of the antiquarian business); you see that the frescoes on the roof are, on the whole, dark with much blue and red in them, the white spaces coming out strongly. This is the characteristic colouring of the partially defunct school of Giotto, becoming merely decorative, and passing into a colourist school which connected itself afterwards with the Venetians. There is an exquisite example of all its specialities in the little Annunciation in the Uffizii, No. 14, attributed to Angelo Gaddi, in which you see the Madonna is stupid, and the angel stupid, but the colour of the whole, as a piece of painted glass, lovely; and the execution exquisite,—at once a painter's and jeweller's; with subtle sense of chiaroscuro underneath; (note the delicate shadow of the Madonna's arm across her breast).

The head of this school was (according to Vasari) Taddeo Gaddi; and henceforward, without further discussion, I shall speak of him as the painter of the roof of the Spanish Chapel,—not without suspicion, however, that his son Angelo may hereafter turn out to have been the better decorator, and the painter of the frescoes from the life of Christ in the north transept of Assisi,—with such assistance as his son or scholars might give—and such change or destruction as time, Antonio Veneziano, or the last operations of the Tuscan railroad company, may have effected on them.

On the other hand, you see that the frescos on the walls are of paler colours, the blacks coming out of these clearly, rather than the whites; but the pale colours, especially, for instance, the whole of the Duomo of Florence in that on your right, very tender and lovely. Also, you may feel a tendency to express much with outline, and draw, more than paint, in the most interesting parts; while in the duller ones, nasty green and yellow tones come out, which prevent the effect of the whole from being very pleasant. These characteristics belong, on the whole, to the school of Siena; and they indicate here the work assuredly of a man of vast power and most refined education, whom I shall call without further discussion, during the rest of this and the following morning's study, Simon Memmi.

And of the grace and subtlety with which he joined his work to that of the Gaddis, you may judge at once by comparing the Christ standing on the fallen gate of the Limbo, with the Christ in the Resurrection above. Memmi has retained the dress and imitated the general effect of the figure in the roof so faithfully that you suspect no difference of mastership—nay, he has even raised the foot in the same awkward way: but you will find Memmi's foot delicately drawn-Taddeo's, hard and rude: and all the folds of Memmi's drapery cast with unbroken grace and complete gradations of shade, while Taddeo's are rigid and meagre; also in the heads, generally Taddeo's type of face is square in feature, with massive and inelegant clusters or volutes of hair and beard; but Memmi's delicate and long in feature, with much divided and flowing hair, often arranged with exquisite precision, as in the finest Greek coins. Examine successively in this respect only the heads of Adam, Abel, Methuselah, and Abraham, in the Limbo, and you will not confuse the two designers any more. I have not had time to make out more than the principal figures in the Limbo, of which indeed the entire dramatic power is centred in the Adam and Eve. The latter dressed as a nun, in her fixed gaze on Christ, with her hands clasped, is of extreme beauty: and however feeble the work of any early painter may be, in its decent and grave inoffensiveness it guides the imagination unerringly to a certain point. How far you are yourself capable of filling up what is left untold and conceiving, as a reality, Eve's first look on this her child, depends on no painter's skill, but on your own understanding. Just above Eve is Abel, bearing the lamb: and behind him, Noah, between his wife and Shem: behind them, Abraham, between Isaac and Ishmael; (turning from Ishmael to Isaac), behind these, Moses, between Aaron and David. I have not identified the others, though I find the white-bearded figure behind Eve called Methuselah in my notes: I know not on what authority. Looking up from these groups, however, to the roof painting, you will at once feel the imperfect grouping and ruder features of all the figures; and the greater depth of colour. We will dismiss these comparatively inferior paintings at once.

The roof and walls must be read together, each segment of the roof forming an introduction to, or portion of, the subject on the wall below. But the roof must first be looked at alone, as the work of Taddeo Gaddi, for the artistic qualities and failures of it.

I. In front, as you enter, is the compartment with the subject of the Resurrection. It is the traditional Byzantine composition: the guards sleeping, and the two angels in white saying to the women, "He is not here," while Christ is seen rising with the flag of the Cross.

But it would be difficult to find another example of the subject, so coldly treated—so entirely without passion or action. The faces are expressionless; the gestures powerless. Evidently the painter is not making the slightest effort to conceive what really happened, but merely repeating and spoiling what he could remember of old design, or himself supply of commonplace for immediate need. The "Noli me tangere," on the right, is spoiled from Giotto, and others before him; a peacock, woefully plumeless and colourless, a fountain, an ill drawn toy-horse, and two toy-children gathering flowers, are emaciate remains of Greek symbols. He has taken pains with the vegetation, but in vain. Yet Taddeo Gaddi was a true painter, a very beautiful designer, and a very amiable person. How comes he to do that Resurrection so badly?

In the first place, he was probably tired of a subject which was a great strain to his feeble imagination; and gave it up as impossible: doing simply the required figures in the required positions. In the second, he was probably at the time despondent and feeble because of his master's death. See Lord Lindsay, II. 273, where also it is pointed out that in the effect of the light proceeding from the figure of Christ, Taddeo Gaddi indeed was the first of the Giottisti who showed true sense of light and shade. But until Lionardo's time the innovation did not materially affect Florentine art.

II. The Ascension (opposite the Resurrection, and not worth looking at, except for the sake of making more sure our conclusions from the first fresco). The Madonna is fixed in Byzantine stiffness, without Byzantine dignity.

III. The Descent of the Holy Ghost, on the left hand. The Madonna and disciples are gathered in an upper chamber: underneath are the Parthians, Medes, Elamites, etc., who hear them speak in their own tongues.

Three dogs are in the foreground—their mythic purpose the same as that of the two verses which affirm the fellowship of the dog in the journey and return of Tobias: namely, to mark the share of the lower animals in the gentleness given by the outpouring of the Spirit of Christ.

IV. The Church sailing on the Sea of the World. St. Peter coming to Christ on the water.

I was too little interested in the vague symbolism of this fresco to examine it with care—the rather that the subject beneath, the literal contest of the Church with the world, needed more time for study in itself alone than I had for all Florence.

On this, and the opposite side of the chapel, are represented, by Simon Memmi's hand, the teaching power of the Spirit of God, and the saving power of the Christ of God, in the world, according to the understanding of Florence in his time.

We will take the side of Intellect first, beneath the pouring forth of the Holy Spirit.

In the point of the arch beneath, are the three Evangelical Virtues. Without these, says Florence, you can have no science. Without Love, Faith, and Hope—no intelligence.

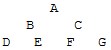

Under these are the four Cardinal Virtues, the entire group being thus arranged:—

A, Charity; flames issuing from her head and hands. B, Faith; holds cross and shield, quenching fiery darts. This symbol, so frequent in modern adaptation from St. Paul's address to personal faith, is rare in older art. C, Hope, with a branch of lilies. D, Temperance; bridles a black fish, on which she stands. E, Prudence, with a book. F, Justice, with crown and baton. G, Fortitude, with tower and sword.

Under these are the great prophets and apostles; on the left,21 David, St. Paul, St. Mark, St. John; on the right, St. Matthew, St. Luke, Moses, Isaiah, Solomon. In the midst of the Evangelists, St. Thomas Aquinas, seated on a Gothic throne.

Now observe, this throne, with all the canopies below it, and the complete representation of the Duomo of Florence opposite, are of finished Gothic of Orecagna's school—later than Giotto's Gothic. But the building in which the apostles are gathered at the Pentecost is of the early Romanesque mosaic school, with a wheel window from the duomo of Assisi, and square windows from the Baptistery of Florence. And this is always the type of architecture used by Taddeo Gaddi: while the finished Gothic could not possibly have been drawn by him, but is absolute evidence of the later hand.

Under the line of prophets, as powers summoned by their voices, are the mythic figures of the seven theological or spiritual, and the seven geological or natural sciences: and under the feet of each of them, the figure of its Captain-teacher to the world.

I had better perhaps give you the names of this entire series of figures

from left to right at once. You will see presently why they are numbered

in a reverse order.

Beneath whom

8. Civil Law. The Emperor Justinian. 9. Canon Law. Pope Clement V. 10.

Practical Theology. Peter Lombard. 11. Contemplative Theology. Dionysius

the Areopagite. 12. Dogmatic Theology. Boethius. 13. Mystic Theology.

St. John Damascene. 14. Polemic Theology. St. Augustine. 7. Arithmetic.

Pythagoras. 6. Geometry. Euclid. 5. Astronomy. Zoroaster. 4. Music.

Tubalcain. 3. Logic. Aristotle. 2. Rhetoric. Cicero. 1. Grammar.

Priscian.

Here, then, you have pictorially represented, the system of manly education, supposed in old Florence to be that necessarily instituted in great earthly kingdoms or republics, animated by the Spirit shed down upon the world at Pentecost. How long do you think it will take you, or ought to take, to see such a picture? We were to get to work this morning, as early as might be: you have probably allowed half an hour for Santa Maria Novella; half an hour for San Lorenzo; an hour for the museum of sculpture at the Bargello; an hour for shopping; and then it will be lunch time, and you mustn't be late, because you are to leave by the afternoon train, and must positively be in Rome to-morrow morning. Well, of your half-hour for Santa Maria Novella,—after Ghirlandajo's choir, Orcagna's transept, and Cimabue's Madonna, and the painted windows, have been seen properly, there will remain, suppose, at the utmost, a quarter of an hour for the Spanish Chapel. That will give you two minutes and a half for each side, two for the ceiling, and three for studying Murray's explanations or mine. Two minutes and a half you have got, then—(and I observed, during my five weeks' work in the chapel, that English visitors seldom gave so much)—to read this scheme given you by Simon Memmi of human spiritual education. In order to understand the purport of it, in any the smallest degree, you must summon to your memory, in the course of these two minutes and a half, what you happen to be acquainted with of the doctrines and characters of Pythagoras, Zoroaster, Aristotle, Dionysius the Areopagite, St. Augustine, and the emperor Justinian, and having further observed the expressions and actions attributed by the painter to these personages, judge how far he has succeeded in reaching a true and worthy ideal of them, and how large or how subordinate a part in his general scheme of human learning he supposes their peculiar doctrines properly to occupy. For myself, being, to my much sorrow, now an old person; and, to my much pride, an old-fashioned one, I have not found my powers either of reading or memory in the least increased by any of Mr. Stephenson's or Mr. Wheatstone's inventions; and though indeed I came here from Lucca in three hours instead of a day, which it used to take, I do not think myself able, on that account, to see any picture in Florence in less time than it took formerly, or even obliged to hurry myself in any investigations connected with it.

Accordingly, I have myself taken five weeks to see the quarter of this picture of Simon Memmi's: and can give you a fairly good account of that quarter, and some partial account of a fragment or two of those on the other walls: but, alas! only of their pictorial qualities in either case; for I don't myself know anything whatever, worth trusting to, about Pythagoras, or Dionysius the Areopagite; and have not had, and never shall have, probably, any time to learn much of them; while in the very feeblest light only,—in what the French would express by their excellent word 'lueur,'—I am able to understand something of the characters of Zoroaster, Aristotle, and Justinian. But this only increases in me the reverence with which I ought to stand before the work of a painter, who was not only a master of his own craft, but so profound a scholar and theologian as to be able to conceive this scheme of picture, and write the divine law by which Florence was to live. Which Law, written in the northern page of this Vaulted Book, we will begin quiet interpretation of, if you care to return hither, to-morrow morning.

THE FIFTH MORNING

THE STRAIT GATEAs you return this morning to St. Mary's, you may as well observe—the matter before us being concerning gates,—that the western façade of the church is of two periods. Your Murray refers it all to the latest of these;—I forget when, and do not care;—in which the largest flanking columns, and the entire effective mass of the walls, with their riband mosaics and high pediment, were built in front of, and above, what the barbarian renaissance designer chose to leave of the pure old Dominican church. You may see his ungainly jointings at the pedestals of the great columns, running through the pretty, parti-coloured base, which, with the 'Strait' Gothic doors, and the entire lines of the fronting and flanking tombs (where not restored by the Devil-begotten brood of modern Florence), is of pure, and exquisitely severe and refined, fourteenth century Gothic, with superbly carved bearings on its shields. The small detached line of tombs on the left, untouched in its sweet colour and living weed ornament, I would fain have painted, stone by stone: but one can never draw in front of a church in these republican days; for all the blackguard children of the neighbourhood come to howl, and throw stones, on the steps, and the ball or stone play against these sculptured tombs, as a dead wall adapted for that purpose only, is incessant in the fine days when I could have worked.

If you enter by the door most to the left, or north, and turn immediately to the right, on the interior of the wall of the façade is an Annunciation, visible enough because well preserved, though in the dark, and extremely pretty in its way,—of the decorated and ornamental school following Giotto:—I can't guess by whom, nor does it much matter; but it is well To look at it by way of contrast with the delicate, intense, slightly decorated design of Memmi,—in which, when you return into the Spanish chapel, you will feel the dependence for its effect on broad masses of white and pale amber, where the decorative school would have had mosaic of red, blue, and gold.

Our first business this morning must be to read and understand the writing on the book held open by St. Thomas Aquinas, for that informs us of the meaning of the whole picture.

It is this text from the Book of Wisdom VII. 6.

"Optavi, et datus est mihi sensus.Invocavi, et venit in me Spiritus Sapientiae,Et preposui illam regnis et sedibus.""I willed, and Sense was given me.I prayed, and the Spirit of Wisdom came upon me.And I set her before, (preferred her to,) kingdomsand thrones."The common translation in our English Apocrypha loses the entire meaning of this passage, which—not only as the statement of the experience of Florence in her own education, but as universally descriptive of the process of all noble education whatever—we had better take pains to understand.

First, says Florence "I willed, (in sense of resolutely desiring,) and Sense was given me." You must begin your education with the distinct resolution to know what is true, and choice of the strait and rough road to such knowledge. This choice is offered to every youth and maid at some moment of their life;—choice between the easy downward road, so broad that we can dance down it in companies, and the steep narrow way, which we must enter alone. Then, and for many a day afterwards, they need that form of persistent Option, and Will: but day by day, the 'Sense' of the rightness of what they have done, deepens on them, not in consequence of the effort, but by gift granted in reward of it. And the Sense of difference between right and wrong, and between beautiful and unbeautiful things, is confirmed in the heroic, and fulfilled in the industrious, soul.