полная версия

полная версияIndian Myth and Legend

Max Müller, in his closing years, faced this aspect of the problem frankly and courageously. “Aryas”, he wrote, “are those who speak Aryan languages, whatever their colour, whatever their blood. In calling them Aryas we predicate nothing of them except that the grammar of their language is Aryan.... I have declared again and again that if I say Aryas, I mean neither blood, nor bones, nor hair, nor skull; I mean simply those who speak an Aryan language. The same applies to Hindus, Greeks, Romans, Germans, Celts, and Slavs. When I speak of these I commit myself to no anatomical characteristics. The blue-eyed and fair-haired Scandinavians may have been conquerors or conquered, they may have adopted the language of their darker lords or their subjects, or vice versa. I assert nothing beyond their language when I call them Hindus, Greeks, Romans, Germans, Celts, and Slavs, and in that sense, and in that sense only, do I say that even the blackest Hindus represent an earlier stage of Aryan speech and thought than the fairest Scandinavians.... To me an ethnologist who speaks of an Aryan race, Aryan blood, Aryan eyes and hair, is as great a sinner as a linguist who speaks of a dolichocephalic dictionary or a brachycephalic grammar.”5

Aryan, however, has been found to be a convenient term, and even ethnologists do not scorn its use, although it has been applied “in a confusing variety of signification by different philologists”. One application of it is to the language group comprising Sanskrit, Persian, Afghan, &c. Some still prefer it to “Indo-European”, which has found rivals in “Afro-European”, among those who connect the Aryan languages with North Africa, and “Afro-Eurasian”, which may be regarded as universal in its racial application, especially if we accept Darwin's theory that the Garden of Eden was located somewhere in Africa.6 We may think of the Aryans as we do of the British when that term is used to include the peoples embraced by the British Empire.

In India the Aryans were from late Vedic times divided into four castes—Brahmans (priests), Kshatriyas (kings and warriors), Vaisyas (traders, &c.), and Sudras (aborigines).

Caste (Varna) signifies “colour”, but it is not certain whether the reference is to be given a physical or mythological application. The first three castes were Aryans, the fairest people; the fourth caste, that comprising the dark-skinned aborigines, was non-Aryan. “Arya”, however, was not always used in the sense that we have been accustomed to apply “Aryo-Indian”. In one of the sacred books of the ancient people it is stated: “The colour of the Brahmans was white; that of the Kshatriyas red; that of the Vaisyas yellow; and that of the Sudras black”.7 This colour reference connects “caste” with the doctrine of yugas, or ages of the universe (Chapter VI).

Risley, dealing with “the leading castes and tribes in Northern India, from the Bay of Bengal to the frontiers of Afghanistan”, concludes from the data obtained from census returns, that we are able “to distinguish two extreme types of feature and physique, which may be provisionally described as Aryan and Dravidian. A third type, which in some respects may be looked upon as intermediate between these two, while in other, and perhaps the most important, points it can hardly be deemed Indian at all, is found along the northern and eastern borders of Bengal. The most prominent characters are a relatively short (brachycephalic) head, a broad face, a short, wide nose, very low in the bridge, and in extreme cases almost bridgeless; high and projecting cheekbones and eyelids, peculiarly formed so as to give the impression that the eyes are obliquely set in the head.... This type … may be conveniently described as Mongoloid....”8

According to Risley, the Aryan type is dolichocephalic (long-headed), “with straight, finely-cut (lepto-rhine) nose, a long, symmetrical narrow face, a well-developed forehead, regular features, and a high facial angle”. The stature is “fairly high”, and the body is “well proportioned, and slender rather than massive”. The complexion is “a very light transparent brown—‘wheat coloured’ is the common vernacular description—noticeably fairer than the mass of the population”.

The Dravidian head, the same authority states, “usually inclines to be dolichocephalic”, but “all other characters present a marked contrast to the Aryan. The nose is thick and broad, and the formula expressing its proportionate dimensions is higher than in any known race, except the Negro. The facial angle is comparatively low; the lips are thick; the face wide and fleshy; the features coarse and irregular.” The stature is lower than that of the Aryan type: “the figure is squat and the limbs sturdy. The colour of the skin varies from very dark brown to a shade closely approaching black.... Between these extreme types”, adds Risley, “we find a large number of intermediate groups.”9

Of late years ethnologists have inclined to regard the lower types represented by hill and jungle tribes, the Veddas of Ceylon, &c., as pre-Dravidians. The brunet and long-headed Dravidians may have entered India long before the Aryans: they resemble closely the Brahui of Baluchistan and the Man-tse of China.

India is thus mainly long-headed (dolichocephalic). We have already seen, however, that in northern and eastern Bengal there are traces of an infusion of Mongolian “broad heads”; another brachycephalic element is pronounced in western India, but it is not Mongolian; possibly we have here evidences of a settlement of Alpine stock. According to Risley, these western broad heads are the descendants of invading Scythians,10 but this theory is not generally accepted.

The Eur-Asian Alpine race of broad heads are a mountain people distributed from Hindu Kush westward to Brittany. On the land bridge of Asia Minor they are represented by the Armenians. Their eastern prehistoric migrations is by some ethnologists believed to be marked by the Ainus of Japan. They are mostly a grey-eyed folk, with dark hair and abundant moustache and beard, as contrasted with the Mongols, whose facial hair is scanty. There are short and long varieties of Alpine stock, and its representatives are usually sturdy and muscular. In Europe these broad-headed invaders overlaid a long-headed brunet population, as the early graves show, but in the process of time the broad heads have again retreated mainly to their immemorial upland habitat. At the present day the Alpine race separates the long-headed fair northern race from what is known as the long-headed dark Mediterranean race of the south.

A slighter and long-headed brunet type is found south of Hindu Kush. Ripley has condensed a mass of evidence to show that it is akin to the Mediterranean race.11 He refers to it as the “eastern branch”, which includes Afghans and Hindus. “We are all familiar with the type,” he says, “especially as it is emphasized by inbreeding and selection among the Brahmans.... There can be no doubt of their (the Eastern Mediterraneans) racial affinities with our Berbers, Greeks, Italians, and Spaniards. They are all members of the same race, at once the widest in its geographical extension, the most populous and the most primitive of our three European types.”12

Professor Elliot Smith supports Professor Ripley in this connection, and includes the Arabs with the southern Persians in the same group, but finding the terms “Hamitic” and “Mediterranean” insufficient, prefers to call this widespread family the “Brown race”, to distinguish its representatives from the fair Northerners, the “yellow” Mongolians, and the “black” negroes.

North of the Alpine racial area are found the nomadic Mongolians, who are also “broad heads”, but with distinguishing facial characteristics which vary in localities. As we have seen, the Mongoloid features are traceable in India. Many settlers have migrated from Tibet, but among the high-caste Indians the Mongoloid eyes and high cheek bones occur in families, suggesting early crossment.

Another distinctive race has yet to be accounted for—the tall, fair, blue-eyed, long-headed Northerners, represented by the Scandinavians of the present day. Sergi and other ethnologists have classed this type as a variety of the Mediterranean race, which had its area of localization on the edge of the snow belt on lofty plateaus and in proximity to the Arctic circle. The theory that the distinctive blondness and great stature of the Northerners were acquired in isolation and perpetuated by artificial selection is, however, more suggestive than conclusive, unless we accept the theory that acquired characteristics can be inherited. How dark eyes became grey or blue, and dark hair red or sandy, is a problem yet to be solved.

The ancestors of this fair race are believed to have been originally distributed along the northern Eur-Asian plateaus; Keane's blonde long-headed Chudes13 and the Wu-suns in Chinese Turkestan are classed as varieties of the ancient Northern stock. An interesting problem is presented in this connection by the fair types among the ancient Egyptians, the modern-day Berbers, and the blondes of the Atlas mountains in Morocco. Sergi is inclined to place the “cradle” of the Northerners on the edge of the Sahara.

The broad-headed Turki and Ugrians are usually referred to as a blend of the Alpine stock and the proto-Northerners, with, in places, Mongolian admixture.

As most of the early peoples were nomadic, or periodically nomadic, there must have been in localities a good deal of interracial and intertribal fusion, with the result that intermediate varieties were produced. It follows that the intellectual life of the mingling peoples would be strongly influenced by admixture as well as by contact with great civilizations.

It now remains for us to deal with the Aryan problem in India. Dr. Haddon considers that the invading Aryans were “perhaps associated with Turki tribes” when they settled in the Punjab.14 Prior to this racial movement, the Kassites, whose origin is obscure, assisted by bands of Aryans, overthrew the Hammurabi dynasty in Babylon and established the Kassite dynasty between 2000 B.C. and 1700 B.C. At this period the domesticated horse was introduced, and its Babylonian name, “the ass of the East”, is an indication whence it came. Another Aryan invasion farther west is marked by the establishment of the Mitanni kingdom between the area controlled by the Assyrians and the Hittites. Its kings had names which are clearly Aryan. These included Saushatar, Artatatama, Sutarna, and Tushratta. The latter was the correspondent in the Tel-el-Amarna letters of his kinsmen the Egyptian Pharaohs, Amenhotep the Magnificent, and the famous Akhenaton. The two royal houses had intermarried after the wars of Thothmes III. It is impossible to fix the date of the rise of the Mitanni power, which held sway for a period over Assyria, but we know that it existed in 1500 B.C. The horse was introduced into Egypt before 1580 B.C.

It is generally believed that the Aryans were the tamers of the horse which revolutionized warfare in ancient days, and caused great empires to be overthrown and new empires to be formed. When the Aryans entered India they had chariots and swift steeds.

There is no general agreement as to the date of settlement in the Punjab. Some authorities favour 2000 B.C., others 1700 B.C.; Professor Macdonell still adheres to 1200 B.C.15 It is possible that the infusion was at first a gradual one, and that it was propelled by successive folk-waves. The period from the earliest migrations until about 800 or 700 B.C. is usually referred to as the Vedic Age, during which the Vedas, or more particularly the invocatory hymns to the deities, were composed and compiled. At the close of this Age the area of Aryan control had extended eastward as far as the upper reaches of the Jumna and Ganges rivers. A number of tribal states or communities are referred to in the hymns.

It is of importance to note that the social and religious organization of the Vedic Aryans was based upon the principle of “father right”, as contrasted with the principle of “mother right”, recognized by representative communities of the Brown race.

Like the Alpine and Mongoloid peoples, the Vedic Aryans were a patriarchal people, mainly pastoral but with some knowledge of agriculture. They worshipped gods chiefly: their goddesses were vague and shadowy: their earth goddess Prithivi was not a Great Mother in the Egyptian and early European sense; her husband was the sky-god Dyaus.

In Egypt the sky was symbolized as the goddess Nut, and the earth as the god Seb, but the Libyans had an earth-goddess Neith. The “Queen of Heaven” was a Babylonian and Assyrian deity. If the Brown race predominated in the Aryan blend during the Vedic Age, we should have found the Great Mother more in prominence.

The principal Aryan deities were Indra, god of thunder, and Agni, god of fire, to whom the greater number of hymns were addressed. From the earliest times, however, Aryan religion was of complex character. We can trace at least two sources of cultural influence from the earlier Iranian period.16 The hymns bear evidence of the declining splendour of the sublime deities Varuna and Mitra (Mithra). It is possible that the conflicts to which references are made in some of the hymns were not unconnected with racial or tribal religious rivalries.

Indra, as we show (Chapter I), bears resemblances to other “hammer gods”. He is the Indian Thor, the angry giant-killer, the god of war and conquests. That his name even did not originate in India is made evident by an inscription at Boghaz Köi, in Asia Minor, referring to a peace treaty between the kings of the Hittites and Mitanni. Professor Hugo Winckler has deciphered from this important survival of antiquity “In-da-ra” as a Mitanni deity who was associated with Varuna, Mitra, and Nasatya.

No evidence has yet been forthcoming to indicate any connection between the Aryans in Mitanni and the early settlers in India. It would appear, however, that the two migrations represented by the widely separated areas of Aryan control, radiated from a centre where the gods Indra, Varuna, and Mitra were grouped in the official religion. The folk-wave which pressed towards the Punjab gave recognition to Agni, possibly as a result of contact, or, more probably, fusion with a tribe of specialized fire-worshippers.

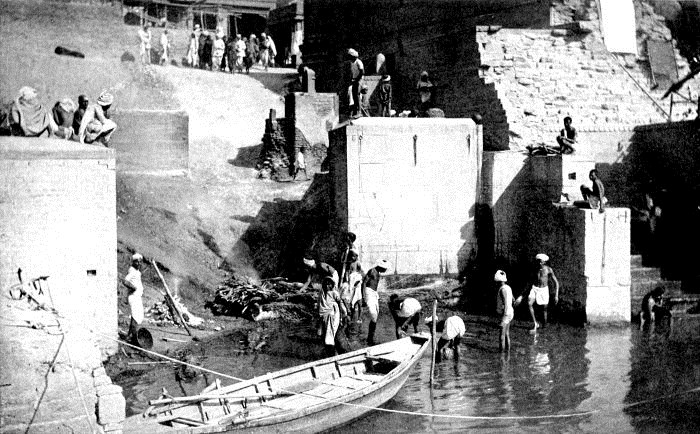

If we separate the Indra from the Agni, cremating worshippers, it will be of interest to follow the ethnic clue which is thus suggested. Modern-day Hindus burn their dead in accordance with the religious practice of the Agni worshippers in the Vedic Age. It is doubtful, however, if all the Aryan invaders practised cremation. There are references to burial in the “house of clay”, and Yama, god of the dead, was adored as the first man who explored the path to the “Land of the Pitris” (Fathers) which lay across the mountains. Professor Oldenberg considers that these burials referred to the disposal of the bones and ashes of the dead.

Professor Macdonell and Dr. Keith, however, do not share Professor Oldenberg's view in this connection.17 They hold that the epithet Agni-dagdhah, “burnt with fire”, “applies to the dead who were burned on the funeral pyre”; the other custom being burial—An-agni-dagdhah, “not burnt with fire”. They also refer to Paroptah, “casting out”, and Uddhitah, “Exposure of the dead”, which are expressions of doubtful meaning. These authorities add: “Burial was clearly not rare in the Rigvedic period: a whole hymn (x, 18) describes the ritual attending it. The dead man was buried apparently in full attire, with his bow in his hand, and probably at one time his wife was immolated to accompany him.... But in the Vedic period both customs appear in a modified form: the son takes the bow from the hand of the dead man, and the widow is led away from her dead husband by his brother or nearest kinsman. A stone is set up between the dead and the living to separate them.”

The Persian fire-worshippers, on the other hand, did not cremate their dead, but exposed them on “towers of silence” to be devoured by vultures, like their modern-day representatives the Parsees, who migrated into India after displacement by the Mohammedans. In Persia the sacred fire was called Atar,18 and was identified with the supreme deity Ahura-Mazda (Ormuzd).

Agni of the Vedic Age is the messenger between gods and men; he conducts the deities to the sacrifice and the souls of the cremated dead to Paradise; he is also the twin brother of Indra.

Now, it is of interest to note, in considering the racial significance of burial rites, that cremation was not practised by the western representatives of the Brown race. In pre-Dynastic Egypt the dead were interred as in Babylon,19 with food vessels, &c. Neolithic man in Europe also favoured crouched burials, and this practice obtained all through the Bronze Age.

The Buriats, who are Mongols dwelling in the vicinity of Lake Baikal, still perpetuate ancient customs, which resemble those of the Vedic Aryans, for they not only practise cremation but also sacrifice the horse (see Chap. V). In his important study of this remarkable people, Mr. Curtin says:20 “The Buriats usually burn their dead; occasionally, however, there is what is called a ‘Russian burial’, that is, the body is placed in a coffin and the coffin is put in the ground. But generally if a man dies in the Autumn or the Winter his body is placed on a sled and drawn by the horse which he valued most to some secluded place in the forest. There a sort of house is built of fallen trees and boughs, the body is placed inside the house, and the building is then surrounded with two or three walls of logs so that no wolf or other animal can get into it.” The horse is afterwards slain. “If other persons die during the winter their bodies are carried to the same house. In this lonely silent place in the forest they rest through the days and nights until the first cuckoo calls, about the ninth of May. Then relatives and friends assemble, and without opening the house burn it to the ground. Persons who die afterwards and during the Summer months are carried to the forest, placed on a funeral pile, and burned immediately. The horse is killed just as in the first instance.”

When the dead are buried without being burned, the corpse is either carried on a wagon, or it is placed upright in front of a living man on horseback so as to ride to its last resting place. The saddle is broken up and laid at the bottom of the grave, while the body is turned to face the south-east. In this case they also sacrifice the horse which is believed to have “gone to his master, ready for use”.

Cremation spread throughout Europe, as we have said, in the Bronze Age. It was not practised by the early folk-waves of the Alpine race which, according to Mosso,21 began to arrive after copper came into use. The two European Bronze Age burial customs, associated with urns of the “food vessel” and “drinking cup” types, have no connection with the practice of burning the dead. The Archæological Ages have not necessarily an ethnic significance. Ripley is of opinion, however, that the practice of cremation indicates a definite racial infusion, but unfortunately it has destroyed the very evidence, of which we are most in need, to solve the problem. It is impossible to say whether the cremated dead were “broad heads” or “long heads”.

“Dr. Sophus Müller of Copenhagen is of opinion that cremation was not practised long before the year 1000 B.C. though it appeared earlier in the south of Europe than in the north. On both points Professor Ridgeway of Cambridge agrees with him.”22

The migration of the cremating people through Europe was westward and southward and northward; they even swept through the British Isles as far north as Orkney. They are usually referred to by archæologists as “Aryans”; some identify them with the mysterious Celts, whom the French, however, prefer to associate, as we have said, with the Alpine “broad heads” especially as this type bulks among the Bretons and the hillmen of France. We must be careful, however, to distinguish between the Aryans and Celts of the philologists and archæologists.

It may be that these invaders were not a race in the proper sense, but a military confederacy which maintained a religious organization formulated in some unknown area where they existed for a time as a nation. The Normans who invaded these islands were Scandinavians23; they settled in France, intermarried with the French, and found allies among the Breton chiefs. It is possible that the cremating people similarly formed military aristocracies when they settled in Hindustan, Mitanni, and in certain other European areas. “Nothing is commoner in the history of migratory peoples,” says Professor Myres,24 “than to find a very small leaven of energetic intruders ruling and organizing large native populations, without either learning their subjects' language or imposing their own till considerably later, if at all.” The archæological evidence in this connection is of particular value. At a famous site near Salzburg, in upper Austria, over a thousand Bronze Age graves were discovered, just over half of which contained unburnt burials. Both methods of interment were contemporary in this district, “but it was noticed that the cremated burials were those of the wealthier class, or of the dominant race.”25 We find also that at Hallstatt “the bodies of the wealthier class were reduced to ashes”.26 In some districts the older people may have maintained their supremacy. At Watsch and St. Margaret in Carniola “a similar blending of the two rites was observed … the unburnt burials being the richer and more numerous”.27 The descent of the Achaens into Greece occurred at a date earlier than the rise of the great Hallstatt civilization. According to Homeric evidence they burned their dead; “though the body of Patroklos was cremated,” however, “the lords of Mycenae were interred unburnt in richly furnished graves”.28 In Britain the cremating people mingled with their predecessors perhaps more intimately than in other areas where there were large states to conquer. A characteristic find on Acklam Wold, Yorkshire, may be referred to. In this grave “a pile of burnt bones was in close contact with the legs of a skeleton buried in the usual contracted position, and they seemed to have been deposited while yet hot, for the knees of the skeleton were completely charred. It has been suggested in cases like this, or where an unburnt body is surrounded by a ring of urn burials, the entire skeleton may be those of chiefs or heads of families, and the burnt bones those of slaves, or even wives, sacrificed at the funeral. The practice of suttee (sati) in Europe rests indeed on the authority of Julius Cæsar, who represents such religious suicides as having, at no remote period from his own, formed a part of the funeral rites of the Gaulish chiefs; and also states that the relatives of a deceased chieftain accused his wives of being accessory to his death, and often tortured them to death on that account.”29 If this is the explanation, the cremating invaders constituted the lower classes in Gaul and Britain, which is doubtful. The practice of burning erring wives, however, apparently prevailed among the Mediterranean peoples. In an Egyptian folk-tale a Pharaoh ordered a faithless wife of a scribe to be burned at the stake.30 One of the Ossianic folk tales of Scotland relates that Grainne, wife of Finn-mac-Coul, who eloped with Diarmid, was similarly dealt with.31 The bulk of the archæological evidence seems to point to the invaders, who are usually referred to as “Aryans” having introduced the cremation ceremony into Europe. Whence came they? The problem is greatly complicated by the evidence from Palestine, where cremation was practised by the hewers of the great artificial caves which were constructed about 3000 B.C.32 As cremation did not begin in Crete, however, until the end of period referred to as “Late Minoan Third” (1450-1200 B.C.)33 it may be that the Palestinian burials are much later than the construction of the caves.

1

Photo. Johnson and Hoffmann

THE CREMATION GHAT, BENARES

It seems reasonable to suppose that the cremation rite originated among a nomadic people. The spirits of the dead were got rid of by burning the body: they departed, like the spirit of Patroklos, after they had received their “meed of fire”. Burial sites were previously regarded as sacred because they were haunted by the spirits of ancestors (the Indian Pitris = “fathers”). A people who burned their dead, and were therefore not bound by attachment to a tribal holy place haunted by spirits, were certainly free to wander. The spirits were transferred by fire to an organized Hades, which appears to have been conceived of by a people who had already attained to a certain social organization and were therefore capable of governing the communities which they subdued. When they mingled with peoples practising other rites and professing different religious beliefs, however, the process of racial fusion must have been accompanied by a fusion of beliefs. Ultimately the burial customs of the subject race might prevail. At any rate, this appears to have been the case in Britain, where, prior to the Roman Age, the early people achieved apparently an intellectual conquest of their conquerors; the practice of the cremation rite entirely vanished.