полная версия

полная версияIndian Myth and Legend

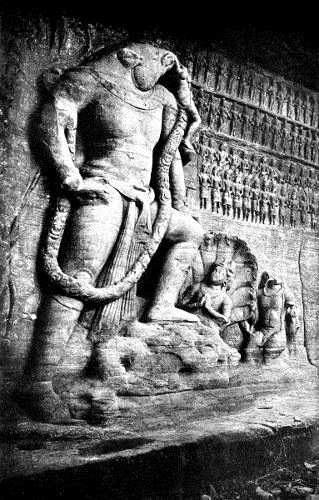

VISHNU UPHOLDING THE UNIVERSE

From a sculpture at Mâmallapuram

Vishnu is a dark god with four arms; in one of his right hands he holds a warshell, and in the other a flaming discus, which destroys enemies and returns after it is flung; in one left hand he holds a mace, and in the other a lotus bloom.

The belief that the Supreme Being from time to time “assumes a human form … for the preservation of rectitude and morality” is an outstanding feature of Vishnuite religion, which teaches that Vishnu was born among men as Ramachandra, Krishna, Balarama, and Buddha. These are the Avataras of the Preserver. Avatara means literally “a descent”, but is used in the sense of an “Incarnation”.

Rama Chandra is the hero of the Ramáyana epic, which is summarized in our closing chapters; he is the human ideal of devotion, righteousness, and manliness, the slayer of the demon Ravana, who oppressed and persecuted mankind.

Krishna and his brother Balarama figure as princes of Dwaraka in the Mahábhárata. Krishna is represented as the teacher of the Vishnuite faith, the devotional religion which displaced the Vedic ceremonies and links Upanishadic doctrines with modern Hinduism. It recognizes that all men are sinful, and preaches salvation by Knowledge which embraces Works. Sinners must surrender themselves to Krishna, the human incarnation (Avatara) of Vishnu, the Preserver, the God of Love.

This faith is unfolded in the famous Bhagavad-gita170 in the Bhishma Parva section of the Mahábhárata epic. Krishna is acting as the counsellor and charioteer of the Pandava warrior Arjuna. Ere the first day's battle of the Great War begins, the human Avatara of Vishnu reveals himself to his friend as the Divine Being, and gives instruction as to how men may obtain salvation.

Krishna teaches that the soul is “unborn, unchangeable, eternal, and ancient”; it is one with the Supreme Soul, Vishnu, the First Cause, the Source of All. The soul “is not slain when the body is slain”; it enters new bodies after each death, or else it secures emancipation from sin and suffering by being absorbed in the World Soul.... All souls have to go through a round of births. “On attaining to Me, however,” says Krishna, “there is no rebirth.”

Krishna gives Salvation to those who obtain “Knowledge of self or Brahma”.... He says: “The one who hath devoted his Self (Soul) to abstraction, casting an equal eye everywhere, beholdeth his Self in all creatures, and all creatures in his Self. Unto him that beholdeth Me in everything and beholdeth everything in Me, I am never lost and he also is never lost in Me. He that worshippeth Me as abiding in all creatures, holding yet that All is One, is a devotee, and whatever mode of life he may lead, he liveth in Me....

“Even if thou art the greatest sinner among all that are sinful, thou shalt yet cross over all transgressions by the raft of Knowledge”.... Knowledge destroys all sins. It is obtained by devotees who, “casting off attachment, perform actions for attaining purity of Self, with the body, the mind, the understanding, and even the senses, free from desire”. To such men “a sod, a stone, and gold are alike”.

Krishna, as Vishnu, is thus revealed: “I am the productive cause of the entire Universe and also its destroyer. There is nothing else that is higher than myself.... I am Om (the Trinity) in all the Vedas, the sound in space, the manliness in man. I am the fragrant odour in earth, the splendour in fire, the life in all creatures, and penance in ascetics.... I am the thing to be known, the means by which everything is cleansed.... I am the soul (self) seated in the heart of every being. I am the beginning, the middle, and the end of all beings.... I am the letter A (in the Sanskrit alphabet).... I am Death that seizeth all, and the source of all that is to be.... He that knoweth me as the Supreme Lord of the worlds, without birth and beginning … is free from all sins.... He who doeth everything for me, who hath me for his supreme object, who is freed from attachment, who is without enmity towards all beings, even he cometh to me.... He through whom the world is not troubled, and who is not troubled by the world, who is free from joy, wrath, fear, and anxieties, even he is dear to me.”

To Arjuna Krishna says: “Exceedingly dear art thou to me. Therefore I will declare what is for thy benefit. Set thy heart on Me, become my devotee, sacrifice to me, bow down to me. Then shalt thou come to me.... Forsaking all (religious) duties, come to me as thy sole refuge. I will deliver thee from all sins. Do not grieve.”

It is, however, added: “This is not to be declared by thee to one who practiseth no austerities, to one who is not a devotee, to one who never waiteth on a preceptor, nor yet to one who calumniateth Me.”

Unbelievers are those who are devoid of knowledge. Krishna says: “One who hath no knowledge and no faith, whose mind is full of doubt, is lost.... Doers of evil, ignorant men, the worst of their species … do not resort to Me.” … Such men “return to the path of the world that is subject to destruction”. He denounces “persons of demoniac natures” because they are devoid of “purity, good conduct, and truth.... They say that the Universe is void of truth, of guiding principle and of ruler.... Depending on this view these men of lost souls, of little intelligence and fierce deeds, these enemies of the world, are born for the destruction of the Universe.” They “cherish boundless hopes, limited by death alone”, and “covet to obtain unfairly hoards of wealth for the gratification of their desires”; they say, “This foe hath been slain by me—I will slay others.... I am lord, I am the enjoyer.... I am rich and of noble birth—who else is there that is like me?… I will make gifts, I will be merry.... Thus deluded by ignorance, tossed about by numerous thoughts, enveloped in the meshes of delusion, attached to the enjoyment of objects of desire, they sink into foul hell.... Threefold is the way to hell, ruinous to the Self (Soul), namely, lust, wrath, likewise avarice.... Freed from these three gates of darkness, a man works out his own welfare, and then repairs to the highest goal.”171

Balarama is an incarnation of the world serpent Shesha. According to the legend, he and Krishna are the sons of Vasudeva and Devakí. It was revealed to Kansa, King of Mat´hurã172, who was a worshipper of Shiva, that a son of Devakí would slay him. His majesty therefore commanded that Devakí's children should be slain as soon as they were born. Balarama, who was fair, was carried safely away. Krishna, the dark son, performed miracles soon after birth. The king had his father and mother fettered, and the doors of the houses were secured with locks. But the chains fell from Vasudeva, and the doors flew open when he stole out into the night to conceal the babe. As he crossed the river Jumna, carrying Krishna on his head in a basket, the waters rose high and threatened to drown him, but the child put out a foot and the river immediately fell and became shallow. In Mathura the two brothers performed miraculous feats during their youth. Indeed, the myths connected with them suggest that their prototypes were voluptuous pastoral gods. Krishna, the flute-player and dancer, is the shepherd lover of the Gopis or herdsmaids, his favourite being Radhá. He was opposed to the worship of Indra, and taught the people to make offerings to a sacred mountain.

22

KRISHNA AND THE GOPIS (HERDSMAIDS)

From a modern sculpture

King Kansa had resort to many stratagems to accomplish the death of Krishna, but his own doom could not be set aside; ultimately he was slain by the two brothers. The Harivamsa, an appendix to the Mahábhárata, which is as long as the Iliad and the Odyssey together, is devoted to the life and adventures of Krishna, who also figures in the Puranas.

Vishnu's Buddha Avatara was assumed, according to orthodox teaching, to bring about the destruction of demons and wicked men who refused to acknowledge the inspiration of the Vedas and the existence of deities, and were opposed to the caste system. This attitude was assumed by the Brahmans because Buddhism was a serious lay revolt against Brahmanical doctrines and ceremonial practices.

Buddha, “the Enlightened”, was Prince Siddartha of the royal family Gautama, which, as elsewhere told, ruled over a Sakya tribe. At his birth marvellous signs foretold his greatness. Reared in luxury, he was kept apart from the common people; but when the time of his awakening came, he was greatly saddened to behold human beings suffering from disease, sorrow, and old age. One night he left his wife and child, and went away to live the life of a contemplative hermit in the forest, with purpose to find a solution for the great problem of human sin and suffering. He came under the influence of Upanishadic doctrines, and at the end of six years he returned and began his mission.

Buddha, the great psychologist, was one of the world's influential teachers, because his doctrines have been embraced in varying degrees of purity by about a third of the human race. Yet they are cold and unsatisfying and gloomy. The “Enlightener's” outlook on life was intensely timid and pessimistic; he was an “enemy of society” in the sense that he made no attempt to effect social reforms so as to minimize human suffering, which touched him with deepest sympathy, but unfortunately filled him with despair; his solution for all problems was Death; he was the apostle of benevolent Nihilism and Idealistic Atheism.

There is no supreme personal god in Buddhism and no hope of immortality. Gods and demons and human beings are “living creatures”; gods have no power over the Universe, and need not be worshipped or sacrificed to, because they are governed by laws, and men have nothing to fear from them.

Buddha denied the existence of the Self-Soul of the Upanishads. Self is not God, in the sense that it is a phase of the World Soul. The “self-state” is, according to the “Enlightener”, a combination of five elements—matter, feeling, imagination, will, and consciousness; these are united by Kamma,173 the influence which causes life to repeat itself. Buddha had accepted, in a limited sense, the theory of Transmigration of Souls. He taught, however, that rebirth was the result of actions and desire. “It is the yearning for existence”, he said, “which leads from new birth to new birth, which finds its desire in different directions, the desire for pleasure, the desire for existence, the desire for power.” Death occurs when the five elements which constitute life are divided; after death nothing remains but the consequences of actions and thoughts. Rebirth follows because “the yearning”, the essence of “works”, brings the elements together again. The individual exists happily, or the reverse, according to his conduct in a former life; sorrow and disease are results of wrong living and wrong thinking in previous states of existence.

23

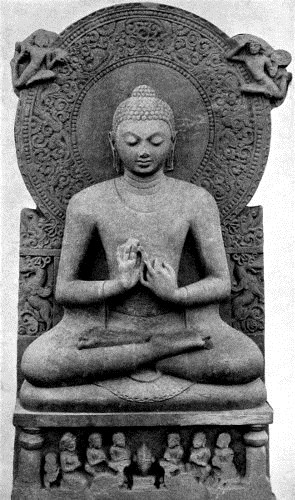

BUDDHA EXPOUNDING THE LAW

The aim of the Buddhist is to become the “master of his fate”. Life to him is hateful because, as the Enlightener taught,“birth is suffering, death is suffering; to be joined to one thou dost not love is suffering, to be divided from thy love is suffering, to fail in thy desire is suffering; in short, the fivefold bonds that unite us to earth—those of the five elements—are suffering”. As there can be no life without suffering in various degrees, it behoves the believer to secure complete emancipation from the fate of being reborn. Life is a dismal and tragic failure. The Buddhist must therefore destroy the influence which unites the five elements and forms another life. He must achieve the complete elimination of inclination—of the yearning for existence. Buddha's “sacred truth”, which secures the desired end, is eightfold—“right belief, right resolve, right speech, right action, right life, right desire, right thought, and right self-absorption”. The reward of the faithful, who attains to perfect knowledge, unsullied by works, is eternal emancipation by Nirvana, undisturbed repose or blissful extinction174, which is the Supreme Good. If there had been no belief in rebirth, the solution would have been found in suicide.

Buddha taught that the four Noble Verities are: (1) pain, (2) desire, the cause of pain, (3) pain is extinguished by Nirvana, (4) the way which leads to Nirvana. The obliteration of Desire is the first aim of the Buddhist. This involves the renunciation of the world and of all evil passions; the believer must live a perfect life according to the Buddhist moral code, which is as strict as it is idealistic in the extreme. “It does not express friendship, or the feeling of particular affection which a man has for one or more of his fellow creatures, but that universal feeling which inspires us with goodwill towards all men and constant willingness to help them.”175

Belief in the sanctity of life is a prevailing note in Buddhism. The teacher forbade the sacrifice of animals, as did Isaiah in Judah.

“To what purpose is the multitude of your sacrifices unto me? saith the Lord: I am full of the burnt offerings of rams, and the fat of fed beasts; and I delight not in the blood of bullocks, or of lambs, or of he goats.”

Isaiah, i, II.Brahmanism was influenced in this regard, for offerings to Vishnu were confined to cakes, curds, sweetmeats, flowers, oblations, &c.

Buddha, the enemy of the priesthood, was of the Kshatriya caste, and his religion appears to have appealed to aristocrats satiated with a luxurious and idle life, who felt like the Preacher that “all is vanity”; it also found numerous adherents among the wandering bands of unorthodox devotees. The perfect Buddhist had to live apart from the world, and engage for long intervals in introspective contemplation so as to cultivate by a stern analytic process that frame of mind which enabled him to obliterate Desire blankly and coldly. Familiar statues of Buddha show the posture which must be assumed; the legs are crossed and twisted, and the hands arranged to suggest inaction; the eyes gaze on the bridge of the nose.

Monastic orders came into existence for men and women, but the status of women was not raised. From these orders were excluded all officials and the victims of infectious and incurable diseases. A lower class of Buddhists engaged in worldly duties. Although Buddha recognized the caste system, his teaching removed its worst features, for Kshatriyas and converted Brahmans could accept food from the Sudras without fear of contamination. Kings embraced the new religion, which ultimately assumed a national character.

Missionaries were from the earliest times sent abroad, and Buddhism spread into Burma, Siam, Anam, Tibet, Mongolia, China, Java, and Japan. The view is suggested that its influence can be traced in Egypt. “From some source,” writes Professor Flinders Petrie, “perhaps the Buddhist mission of Asoka, the ascetic life of recluses was established in the Ptolemaic times, and monks of the Serapeum illustrated an ideal to man which had been as yet unknown in the West. This system of monasticism continued until Pachomios, a monk of Serapis in Upper Egypt, became the first Christian monk in the reign of Constantine.”176

Jainism, like Buddhism, was also a revolt against Brahmanic orthodoxy, and drew its teachers and disciples chiefly from the aristocratic class. It was similarly influenced in its origin by the Upanishads. Jainites believe, however, in soul and the world soul; they recognize the Hindu deities, but only as exalted souls in a state of temporary bliss achieved by their virtues; they also worship a number of “conquerors” or “openers of the way”, as Buddhism, in debased form, recognizes Buddha and his disciples as gods, and allows the worship here of a tooth and there of a hair of the Enlightener, as well as sacred mounds connected with his pilgrimages. In the gloomy creed of the Jainites it is taught that “emancipation” may be hastened by rigid austerities which entail systematic starvation. Many Jainites have in their holy places given up their lives in this manner, but the practice is now obsolete.

In the Age which witnessed the decline of Buddhism in India, and the rise of reformed Brahmanism, the religious struggle was productive of the long poems called the Puranas (old tales) to which we have referred. In these productions some of the ancient myths about the gods were preserved and new myths were formulated. They were meant for popular instruction, and especially to make converts among the unlettered masses. Their authors were chiefly of the Vishnu cult, which had perpetuated the teachings of the unknown sages who at the close of the Brahmanical Age revolted against impersonal Pantheism, the ritualistic practices of the priesthood, and the popular conceptions regarding the Vedic deities who ensured worldly prosperity, but exercised little influence on the character of the individual.

Indra and Agni and other popular deities were not, however, excluded from the Pantheon, but were divested of their ancient splendour and shown to be subject to the sway of Brahma, their Lord and Creator, whose attributes they symbolized in their various spheres of activity. Vishnuites taught that Vishnu was Brahma, and Shivaites that Shiva was the supreme deity.

In this way, it would appear, the authors of the Puranas effected a compromise between immemorial beliefs and practices and the higher religious conceptions towards which the people were being gradually elevated. A similar policy was adopted by Pope Gregory the Great, who in the year 601 caused the Archbishop of Canterbury to be instructed to infuse Pagan ceremonials with Christian symbolism. It was decreed that heathen temples should be changed into churches, and days consecrated to sacrificial ceremonies to be observed as Christian festivals. The Anglo-Saxons were not to be permitted to “sacrifice animals to the Devil”, but to kill them for human consumption “to the praise of God”, so that “while they retained some outward joys they might give more ready response to inward joys”. The Pope added: “It is not possible to cut off everything at once from obdurate minds; he who endeavours to climb to the highest place must rise not by bounds, but by degrees or steps.”177

It is necessary for us, therefore, in dealing with Puranic beliefs, and the movement which culminated in modern-day Hinduism, to make a distinction between the popular faith and the beliefs of the most enlightened Brahmans, and also between the process of mythology-making and the development of religious ideas.

In early Puranic times, when Brahmanism was revived, Vishnu's benevolent character was exalted to so high a degree that, it was taught, even demons might secure salvation through his grace. Prahlada, son of the King of the Danavas, worshipped Vishnu. As a consequence, terrible punishments were inflicted upon him by his angry father. At length Vishnu appeared in the Danava palace as the Nrisinha incarnation (half man, half lion), and slew the presumptuous giant king who had aspired to control the Universe.

Another incarnation of Vishnu was the boar, Varáha. A demon named Hiranyaksha had claimed the earth, when at the beginning of one of the Yugas it was raised from the primordial deep by the Creator in the form of a boar. Vishnu slew the demon for the benefit of the human race. Earlier forms of this myth recognize Brahma, or Prajapati, as the boar. In Taittiriya Brahmana it is set forth: “This Universe was formerly water, fluid; with that (water) Prajapati practised arduous devotions (saying), ‘How shall this universe be (developed)?’ He beheld a lotus leaf standing. He thought, ‘There is something on which this rests.’ He as a boar—having assumed that form—plunged beneath towards it. He found the earth down below. Breaking off (a portion of) her, he rose to the surface.”

This treatment of the boar is of special interest. In Egypt the boar was the demon Set, and the “black pig” is the devil in Wales and Scotland, and also in a “layer” of Irish mythology. Hatred of pork prevailed in Egypt and its vicinity, and still lingers in parts of Ireland and Wales, but especially in the Scottish Highlands. The Gauls, like the Aryans of India, did not regard the boar as a demon, and they ate pork freely, as did also the Achæans and the Germanic peoples. Roast pig is provided in Valhal and in the Irish Danann Paradise, but the Irish “devil”, Balor, who resembles the Asura king of India, had a herd of black pigs.

The struggle between Kshatriyas and Brahmans is reflected in Vishnu's incarnation as Parasu-rama (Rama with the axe). He clears the earth twenty-one times of the visible Kshatriyas, but on each occasion a few survive to perpetuate the caste.

Jagannath178 is also regarded as a form of Vishnu, although apparently not of Brahmanic origin. He is represented by three forms, representing the dark Krishna, the fair Balarama, and their sister, Subhadra. Once a year the idol is bathed and afterwards taken forth in a great car, which is dragged by pious worshippers. Some have considered it a meritorious act to commit suicide by being crushed under its wheels.

24

THE BOAR INCARNATION OF VISHNU RAISING THE EARTH FROM THE DEEP

From a rock sculpture at Udayagiri

It is believed that Vishnu will yet appear as Kalki, riding on a white horse and grasping a flaming sword. He will slay the enemies of evil and re-establish pure religion. Many pious Vishnuites in our own day look forward to the coming of their supreme deity with fear and trembling, but not without inflexible faith.

CHAPTER VIII

Divinities of the Epic Period

The Great Indian Epics—Utilized by the Brahmans—The Story of Manu—Universal Cataclysm—How Amrita (Ambrosia) was obtained—Churning of the Ocean—The Demon Devourer of Sun and Moon—Garuda, the Man Eagle—Attributes of the God Shiva—Comparison with Irish Balor—Rise of the Goddesses—Saraswati and Lakshmi or Sri—Fierce Durga and Kali—Sati, the Ideal Hindu Wife—Legend of the Ganges—The Celestial Rishis—Vishwamitra and Vasishtha—History in the Vedas—Wars between Aryan Tribes—Kernel of Mahábhárata Epic.

The history of Brahmanism during the Buddhist Age is enshrined in the great epics Mahábhárata and Ramáyana, which had their origin before B.C. 500, and continued to grow through the centuries.

The Mahabharata, which deals with the Great War for ascendancy between two families descended from King Bharata, has been aptly referred to as “the Iliad of India”. It appears to have evolved from a cycle of popular hero songs, but after assuming epic form it was utilized by the Brahmans for purposes of religious propaganda. The warriors were represented as sons of gods or allies of demons, and the action of the original narrative was greatly hampered by inserting long speeches and discussions regarding Brahmanic conceptions and beliefs. An excellent example of this process is afforded by the famous Bhagavad-gita, from which we have quoted in the previous chapter. The narrative of the first day's battle is interrupted to allow Krishna to expound the doctrines of the Vaishnava faith, with purpose to make converts to the cult of Vishnu. Almost every incident in the poem is utilized in a similar manner. In fact the epic, as we are informed in the opening section, “furnisheth the means of arriving at the knowledge of Brahma”. The priests, with this aim in view, loaded the chariots of heroes with religious treatises, and transformed a tribal struggle for supremacy into a great holy war. If the Iliad survived to us only in Pope's translation, and our theologians had scattered through it, say, metrical renderings of Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, the Thirty-nine Articles of the Church of England, the Westminster Confession of Faith, Fox's Book of Martyrs, and a few representative theological works of rival sects, a fate similar to that which has befallen the Mahabharata would now overshadow the great Homeric masterpiece. The “Iliad of India” is a part of what may be called the Hindu Bible, which embraces the Ramayana, the Vedas, the Upanishads, the Puranas, &c.