полная версия

полная версияThe Battle with the Slum

The slum has even been washed. We tried that on Hester Street years ago, in the age of cobblestone pavements, and the result fairly frightened us. I remember the indignant reply of a well-known citizen, a man of large business responsibility and experience in the handling of men, to whom the office of street-cleaning commissioner had been offered, when I asked him if he would accept. "I have lived," he said, "a blameless life for forty years, and have a character in the community. I cannot afford—no man with a reputation can afford—to hold that office; it will surely wreck it." It made Colonel Waring's reputation. He took the trucks from the streets. Tammany, in a brief interregnum of vigor under Mayor Grant, had laid the axe to the unsightly telegraph poles and begun to pave the streets with asphalt, but it left the trucks and the ash barrels to Colonel Waring as hopeless. Trucks have votes; at least their drivers have. Now that they are gone, the drivers would be the last to bring them back; for they have children, too, and the rescued streets gave them their first playground. Perilous, begrudged by policeman and storekeeper, though it was, it was still a playground.

It costs a Dollar a Month to sleep in these Sheds.

But one is coming in which the boy shall rule unchallenged. The Mulberry Bend Park kept its promise. Before the sod was laid in it two more were under way in the thickest of the tenement house crowding, and though the landscape gardener has tried twice to steal them, he will not succeed. Play piers and play schools are the order of the day. We shall yet settle the "causes that operated sociologically" on the boy with a lawn-mower and a sand heap. You have got your boy, and the heredity of the next one, when you can order his setting.

Social halls for the older people's play are coming where the saloon has had a monopoly of the cheer too long. The labor unions and the reformers work together to put an end to sweating and child-labor. The gospel of less law and more enforcement acquired standing while Theodore Roosevelt sat in the governor's chair rehearsing to us Jefferson's forgotten lesson that "the whole art and science of government consists in being honest." With a back door to every ordinance that touched the lives of the people, if indeed the whole thing was not the subject of open ridicule or the vehicle of official blackmail, it seemed as if we had provided a perfect municipal machinery for bringing the law into contempt with the young, and so for wrecking citizenship by the shortest cut.

Of free soup there is an end. It was never food for free men. The last spoonful was ladled out by yellow journalism with the certificate of the men who fought Roosevelt and reform in the police board that it was good. It is not likely that it will ever plague us again. Our experience has taught us a new reading of the old word that charity covers a multitude of sins. It does. Uncovering some of them has kept us busy since our conscience awoke, and there are more left. The worst of them all, that awful parody on municipal charity, the police station lodging room, is gone, after twenty years of persistent attack upon the foul dens,—years during which they were arraigned, condemned, indicted by every authority having jurisdiction, all to no purpose. The stale beer dives went with them and with the Bend, and the grip of the tramp on our throat has been loosened. We shall not easily throw it off altogether, for the tramp has a vote, too, for which Tammany, with admirable ingenuity, found a new use, when the ante-election inspection of lodging houses made them less available for colonization purposes than they had been. Perhaps I should say a new way of very old use. It was simplicity itself. Instead of keeping tramps in hired lodgings for weeks at a daily outlay, the new way was to send them all to the island on short commitments during the canvass, and vote them from there en bloc at the city's expense.

Mulberry Street Police Station. Waiting for the Lodging to open.

Time and education must solve that, like so many other problems which the slum has thrust upon us. They are the forces upon which, when we have gone as far as our present supply of steam will carry us, we must always fall back; and this we may do with confidence so long as we keep stirring, if it is only marking time, when that is all that can be done. It is in the retrospect that one sees how far we have come, after all, and from that gathers courage for the rest of the way. Thirty-two years have passed since I slept in a police station lodging house, a lonely lad, and was robbed, beaten, and thrown out for protesting; and when the vagrant cur that had joined its homelessness to mine, and had sat all night at the door waiting for me to come out,—it had been clubbed away the night before,—snarled and showed its teeth at the doorman, raging and impotent I saw it beaten to death on the step. I little dreamed then that the friendless beast, dead, should prove the undoing of the monstrous wrong done by the maintenance of these evil holes to every helpless man and woman who was without shelter in New York; but it did. It was after an inspection of the lodging rooms, when I stood with Theodore Roosevelt, then president of the police board, in the one where I had slept that night, and told him of it, that he swore they should go. And go they did, as did so many another abuse in those two years of honest purpose and effort. I hated them. It may not have been a very high motive to furnish power for municipal reform; but we had tried every other way, and none of them worked. Arbitration is good, but there are times when it becomes necessary to knock a man down and arbitrate sitting on him, and this was such a time. It was what we started out to do with the rear tenements, the worst of the slum barracks, and it would have been better had we kept on that track. I have always maintained that we made a false move when we stopped to discuss damages with the landlord, or to hear his side of it at all. His share in it was our grievance; it blocked the mortality records with its burden of human woe. The damage was all ours, the profit all his. If there are damages to collect, he should foot the bill, not we. Vested rights are to be protected, but, as I have said, no man has a right to be protected in killing his neighbor.

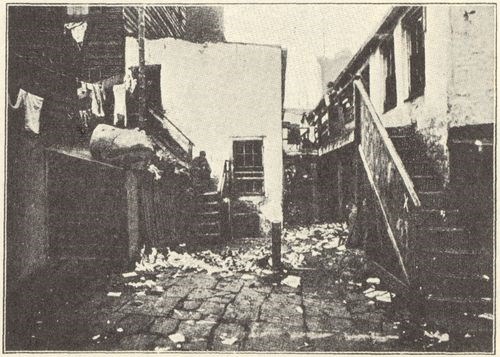

Night in Gotham Court.

However, they are down, the worst of them. The community has asserted its right to destroy tenements that destroy life, and for that cause. We bought the slum off in the Mulberry Bend at its own figure. On the rear tenements we set the price, and set it low. It was a long step. Bottle Alley is gone, and Bandits' Roost. Bone Alley, Thieves' Alley, and Kerosene Row,—they are all gone. Hell's Kitchen and Poverty Gap have acquired standards of decency; Poverty Gap has risen even to the height of neckties. The time is fresh in my recollection when a different kind of necktie was its pride; when the boy-murderer—he was barely nineteen—who wore it on the gallows took leave of the captain of detectives with the cheerful invitation to "come over to the wake. They'll have a hell of a time." And the event fully redeemed the promise. The whole Gap turned out to do the dead bully honor. I have not heard from the Gap, and hardly from Hell's Kitchen, in five years. The last news from the Kitchen was when the thin wedge of a column of negroes, in their up-town migration, tried to squeeze in, and provoked a race war; but that in fairness should not be laid up against it. In certain local aspects it might be accounted a sacred duty; as much so as to get drunk and provoke a fight on the anniversary of the battle of the Boyne. But on the whole the Kitchen has grown orderly. The gang rarely beats a policeman nowadays, and it has not killed one in a long while.

So, one after another, the outworks of the slum have been taken. It has been beaten in many battles; even to the double-decker tenement on the twenty-five-foot lot have we put a stop. But its legacy is with us in the habitations of two million souls. This is the sore spot, and as against it all the rest seems often enough unavailing. Yet it cannot be. It is true that the home, about which all that is to work for permanent progress must cluster, is struggling against desperate odds in the tenement, and that the struggle has been reflected in the morals of the people, in the corruption of the young, to an alarming extent; but it must be that the higher standards now set up on every hand, in the cleaner streets, in the better schools, in the parks and the clubs, in the settlements, and in the thousand and one agencies for good that touch and help the lives of the poor at as many points, will tell at no distant day, and react upon the homes and upon their builders. In fact, we know it is so from our experience last fall, when the summons to battle for the people's homes came from the young on the East Side. It was their fight for the very standards I spoke of, their reply to the appeal they made to them.

To any one who knew that East Side ten years ago, the difference between that day and this in the appearance of the children whom he sees there must be striking. Rags and dirt are now the exception rather than the rule. Perhaps the statement is a trifle too strong as to the dirt; but dirt is not harmful except when coupled with rags; it can be washed off, and nowadays is washed off where such a thing would have been considered affectation in the days that were. Soap and water have worked a visible cure already that goes more than skin-deep. They are moral agents of the first value in the slum. And the day is coming soon now, when with real rapid transit and the transmission of power to suburban workshops the reason for the outrageous crowding shall cease to exist. It has been a long while, a whole century of city packing, closer and more close; but it looks as if the tide were to turn at last. Meanwhile, philanthropy is not sitting idle and waiting. It is building tenements on the humane plan that lets in sunshine and air and hope. It is putting up hotels deserving of the name for the army that but just now had no other home than the cheap lodging houses which Inspector Byrnes fitly called "nurseries of crime." These also are standards from which there is no backing down, even if coming up to them is slow work: and they are here to stay, for they pay. That is the test. Not charity, but justice,—that is the gospel which they preach.

A Mulberry Bend Alley.

Flushed with the success of many victories, we challenged the slum to a fight to the finish in 1897, and bade it come on. It came on. On our side fought the bravest and best. The man who marshalled the citizen forces for their candidate had been foremost in building homes, in erecting baths for the people, in directing the self-sacrificing labors of the oldest and worthiest of the agencies for improving the condition of the poor. With him battled men who had given lives of patient study and effort to the cause of helping their fellow-men. Shoulder to shoulder with them stood the thoughtful workingman from the East Side tenement. The slum, too, marshalled its forces. Tammany produced its notes. It pointed to the increased tax rate, showed what it had cost to build schools and parks and to clean house, and called it criminal recklessness. The issue was made sharp and clear. The war cry of the slum was characteristic: "To hell with reform!" We all remember the result. Politics interfered, and turned victory into defeat. We were beaten. I shall never forget that election night. I walked home through the Bowery in the midnight hour, and saw it gorging itself, like a starved wolf, upon the promise of the morrow. Drunken men and women sat in every doorway, howling ribald songs and curses. Hard faces I had not seen for years showed themselves about the dives. The mob made merry after its fashion. The old days were coming back. Reform was dead, and decency with it.

"In the hallway I ran across two children, little tots, who were inquiring their way to 'the commissioner.'"

A year later, I passed that same way on the night of election.14 The scene was strangely changed. The street was unusually quiet for such a time. Men stood in groups about the saloons, and talked in whispers, with serious faces. The name of Roosevelt was heard on every hand. The dives were running, but there was no shouting, and violence was discouraged. When, on the following day, I met the proprietor of one of the oldest concerns in the Bowery,—which, while doing a legitimate business, caters necessarily to its crowds, and therefore sides with them,—he told me with bitter reproach how he had been stricken in pocket. A gambler had just been in to see him, who had come on from the far West, in anticipation of a wide-open town, and had got all ready to open a house in the Tenderloin. "He brought $40,000 to put in the business, and he came to take it away to Baltimore. Just now the cashier of – Bank told me that two other gentlemen—gamblers? yes, that's what you call them—had drawn $130,000 which they would have invested here, and had gone after him. Think of all that money gone to Baltimore! That's what you've done!"

I went over to police headquarters, thinking of the sad state of that man, and in the hallway I ran across two children, little tots, who were inquiring their way to "the commissioner." The older was a hunchback girl, who led her younger brother (he could not have been over five or six years old) by the hand. They explained their case to me. They came from Allen Street. Some "bad ladies" had moved into the tenement, and when complaint was made that sent the police there, the children's father, who was a poor Jewish tailor, was blamed. The tenants took it out of the boy by punching his nose till it bled. Whereupon the children went straight to Mulberry Street to see "the commissioner" and get justice. It was the first time in twenty years that I had known Allen Street to come to police headquarters for justice and in the discovery that the legacy of Roosevelt had reached even to the little children I read the doom of the slum, despite its loud vauntings.

No, it was not true that reform was dead, with decency. We had our innings four years later and proved it; of which more farther on. It was not the slum that had won; it was we who had lost. We were not up to the mark,—not yet. We may lose again, more than once, but even our losses shall be our gains, if we learn from them. And we are doing that. New York is a many times cleaner and better city to-day than it was twenty or even ten years ago. Then I was able to grasp easily the whole plan for wresting it from the neglect and indifference that had put us where we were. It was chiefly, almost wholly, remedial in its scope. Now it is preventive, constructive, and no ten men could gather all the threads and hold them. We have made, are making, headway, and no Tammany has the power to stop us. They know it, too, at the Hall, and were in such frantic haste to fill their pockets this last time that they abandoned their old ally, the tax rate, and the pretence of making bad government cheap government. Tammany dug its arms into the treasury fairly up to the elbows, raising taxes, assessments, and salaries all at once, and collecting blackmail from everything in sight. Its charges for the lesson it taught us came high; but we can afford to pay them. If to learning it we add common sense, we shall discover the bearings of it all without trouble. Yesterday I picked up a book,—a learned disquisition on government,—and read on the title-page, "Affectionately dedicated to all who despise politics." That was not common sense. To win the battle with the slum, we must not begin by despising politics. We have been doing that too long. The politics of the slum are apt to be like the slum itself, dirty. Then they must be cleaned. It is what the fight is about. Politics are the weapon. We must learn to use it so as to cut straight and sure. That is common sense, and the golden rule as applied to Tammany.

Some years ago, the United States government conducted an inquiry into the slums of great cities. To its staff of experts was attached a chemist, who gathered and isolated a lot of bacilli with fearsome Latin names, in the tenements where he went. Among those he labelled were the Staphylococcus pyogenes albus, the Micrococcus fervidosus, the Saccharomyces rosaceus, and the Bacillus buccalis fortuitis. I made a note of the names at the time, because of the dread with which they inspired me. But I searched the collection in vain for the real bacillus of the slum. It escaped science, to be, identified by human sympathy and a conscience-stricken community with that of ordinary human selfishness. The antitoxin has been found, and it is applied successfully. Since justice has replaced charity on the prescription the patient is improving. And the improvement is not confined to him; it is general. Conscience is not a local issue in our day. A few years ago, a United States senator sought reëlection on the platform that the decalogue and the golden rule were glittering generalities that had no place in politics, and lost. We have not quite reached the millennium yet, but since then a man was governor in the Empire State, elected on the pledge that he would rule by the ten commandments. These are facts that mean much or little, according to the way one looks at them. The significant thing is that they are facts, and that, in spite of slipping and sliding, the world moves forward, not backward. The poor we shall have always with us, but the slum we need not have. These two do not rightfully belong together. Their present partnership is at once poverty's worst hardship and our worst blunder.

CHAPTER III

THE DEVIL'S MONEY

That was what the women called it, and the name stuck and killed the looters. The young men of the East Side began it, and the women finished it. It was a campaign of decency against Tammany, that one of 1901 of which I am going to make the record brief as may be, for we all remember it; and also, thank God, that decency won the fight.

If ever inhuman robbery deserved the name, that which caused the downfall of Tammany surely did. Drunk with the power and plunder of four long unchallenged years, during which the honest name of democracy was pilloried in the sight of all men as the active partner of blackmail and the brothel, the monstrous malignity reached a point at last where it was no longer to be borne. Then came the crash. The pillory lied. Tammany is no more a political organization than it is the benevolent concern it is innocently supposed to be by some people who never learn. It neither knows nor cares for principles. "Koch?" said its President of the Health Department when mention was made in his hearing of the authority of the great German doctor, "who is that man Koch you are talking about?" And he was typical of the rest. His function was to collect the political revenue of the department, and the city was overrun with smallpox for the first time in thirty years. The police force, of whom Roosevelt had made heroes, became the tools of robbers. Robbery is the business of Tammany. For that, and for that only, is it organized. Politics are merely the convenient pretence. I do not mean that every Tammany man is a thief. Probably the great majority of its adherents honestly believe that it stands for something worth fighting for,—for personal freedom, for the people's cause,—and their delusion is the opportunity of scoundrels. They have never understood its organization or read its history.

For a hundred years that has been an almost unbroken record of fraud and peculation. Its very founder, William Mooney, was charged with being a deserter from the patriot army to the British forces. He was later on removed from office as superintendent of the almshouse for swindling the city. Aaron Burr plotted treason within its councils. The briefest survey of the administration of the metropolis from his day down to that of Tweed shows a score of its conspicuous leaders removed, indicted, or tried, for default, bribe-taking, or theft; and the fewest were punished. The civic history of New York to the present day is one long struggle to free itself from its blighting grip. Its people's parties, its committees of seventy, were ever emergency measures to that end, but they succeeded only for a season. There have been decent Tammany mayors, but not for long. There have been attempts to reform the organization from within, but they have been failures. You cannot reform an "organized appetite" except by reforming it away. And then there would be nothing left of the organization.

For whatever the rank and file have believed, the organization has never been anything else but the means of satisfying the appetite that never will be cloyed. Whatever principles it has professed, they have served the purpose only of filling the pockets of the handful of men who rule its inner councils and use it to their own enrichment and our loss and disgrace. We have heard its most successful leader testify brazenly before the Mazet legislative committee that he was in politics working for his own pocket all the time. That was his principle. And his followers applauded till the room rang.

That is the Tammany which has placed murderers and gamblers in its high seats. That is the Tammany which you have to fight at every step when battling with the slum; the Tammany which, unmasked and beaten by the Parkhurst and Lexow disclosures, came back with the Greater New York to exploit the opportunity reform had made for itself, and gave us a lesson we will not soon forget. For at last it dropped all pretence and showed its real face to us.

Civil service reform was thrown to the winds; the city departments were openly parcelled out among the district leaders: a $2000 office to one,—two $1000 to another to even up. That is the secret of the "organization" which politicians admire. It does make a strong body. How it served the city in one department, the smallpox epidemic bore witness. That department, the pride of the city and its mainstay in days of danger, was wrecked. The first duty of the new president, when the four years were over and Tammany out again, was to remove more than a hundred and fifty useless employees. Their only function had been to draw the salaries which the city paid. The streets that had been clean became dirty—the "voter" was back "behind the broom"—and they swarmed once more with children for whom there was no room in school. Officials who drew big salaries starved the inmates of the almshouse on weak tea and dry bread, and Bellevue, the poor people's hospital, became a public scandal. In one night there were five drunken fights, one of them between two of the attendants who dropped the corpse they were carrying to the morgue and fought over it. The tenements were plunged back into the foulness of their worst day; the inspectors were answerable, not to the Health Board, but to the district leader, and the landlord who stood well with him thumbed his nose at them and at their orders to clean up. The neighborhood parks, acquired at such heavy sacrifice, lay waste. Tammany took no step toward improving them. One it did take up at Fort George; and though the property only cost the city $600,000, the bills for taking it were $127,467. That is the true Tammany style. In the Seward Park, where the need of relief was greatest, Tammany election district captains built booths, rent free, for the sale of dry goods and fish. That was "their share." Wealthy corporations were made to pay heavily for "peace"; timid storekeepers were blackmailed. One, a Jew, told his story: he was ordered to pay five dollars a week for privilege of keeping open Sundays. He paid, and they asked ten. When he refused, he was told that it would be the worse for him. He closed up. The very next week he was sued for a hundred dollars by a man of whom he had never borrowed anything. He did not defend the suit, and it went against him. In three days the sheriff was in his store. He knew the hopelessness of it then, and went out and mortgaged his store and paid the bill. The next week another man sued him for a hundred dollars he did not owe. He went and threw himself on his mercy, and the man let him off for the costs.