полная версия

полная версияThe Battle with the Slum

It helped, when that story was told. There is nothing in our day like the facts, and they came out that time. There was the roof-garden on the Educational Alliance Building with its average of more than five thousand a day, young and old, last summer (a total of 344,424 for the season), in flat contradiction of the claim that the children "wouldn't go up on the roof." Not, surely, if it was only to encounter a janitor with a club there. But a brass band now? There were a few professional shivers at that, but our experience with the one we set playing in the park on Sunday, years ago, came to the rescue. When it had played its last piece to end and there burst forth as with one voice from the mighty throng, "Praise God from whom all blessings flow!" some doubts were set at rest for all time. They were never sensible, but after that they were silly.

So the janitor was bidden bring out his key. Electric lights were strung. "We will save the money somewhere else," said Mayor Low. The experiment was made with five schools, all on the crowded East Side.

I was at dinner with friends at the University Settlement, directly across from which, on the other corner, is one of the great new schools, No. 20, I think. We had got to the salad when through the open window there came a yell of exultation and triumph that made me fairly jump in my chair. Below in the street a mighty mob of children and mothers had been for half an hour besieging the door of the schoolhouse. The yell signalized the opening of it by the policeman in charge. Up the stairs surged the multitude. We could see them racing, climbing, toiling, according to their years, for the goal above where the band was tuning up. One little fellow with a trousers leg and a half, and a pair of suspenders and an undershirt as his only other garments, labored up the long flight, carrying his baby brother on his back. I watched them go clear up, catching glimpses of them at every turn, and then I went up after.

I found them in a corner, propped against the wall, a look of the serenest bliss on their faces as they drank it all in. It was their show at last. The band was playing "Alabama," and fifteen hundred boys and girls were dancing, hopping, prancing to the tune, circling about and about while they sang and kept time to the music. When the chorus was reached, every voice was raised to its shrillest pitch: "Way—down—yonder—in—the—cornfield." And for once in my life the suggestion of the fields and the woods did not seem hopelessly out of place in the Tenth Ward crowds. Baby in its tired mother's lap looked on wide-eyed, out of the sweep of the human current.

The band ceased playing, and the boys took up some game, dodging hither and thither in pursuit of a ball. How they did it will ever be a mystery to me. There did not seem to be room for another child, but they managed as if they had it all to themselves. There was no disorder; no one was hurt, or even knocked down, unless in the game, and that was the game, so it was as it should be. Right in the middle of it, the strains of "Sunday Afternoon," all East Side children's favorite, burst forth, and out of the seeming confusion came rhythmic order as the whole body of children moved, singing, along the floor.

Down below, the deserted street—deserted for once in the day—had grown strangely still. The policeman nodded contentedly: "good business, indeed." This was a kind of roof patrol he could appreciate. Nothing to do; less for to-morrow, for here they were not planning raids on the grocer's stock. They were happy, and when children are happy, they are safe, and so are the rest of us. It is the policeman's philosophy, and it is worth taking serious note of.

A warning blast on a trumpet and the "Star-spangled Banner" floated out over the house-tops. The children ceased dancing: every boy's cap came off, and the chorus swelled loud and clear:

"—in triumph shall waveO'er the land of the free and the home of the brave."The light shone upon the thousand upturned faces. Scarce one in a hundred of them all that did not bear silent witness to persecution which had driven a whole people over the sea, without home, without flag. And now—my eyes filled with tears. I said it: I am getting old and silly.

The Fellows and Papa and Mamma shall be invited in yet.

It was so at the still bigger school at Hester and Orchard streets. At the biggest of them all, and the finest, the same No. 177 where the janitor's assistant "shooed" the children away with his club, the once dismal yard had been festooned with electric lamps that turned night into day, and about the band-stand danced nearly three thousand boys and girls to the strains of "Money Musk," glad to be alive and there. A ball-room forsooth! And it is going to be better still; for once the ice has been broken, there are new kinks coming in this dancing programme that is the dear dissipation of the East Side. What is to hinder the girls, when the long winter days come, from inviting in the fellows, and papa and mamma, for a real dance that shall take the wind out of the sails of the dance-halls? Nothing in all the world. Nor even will there be anything to stop Superintendent Maxwell from taking a turn himself, as he said he would, or me either, if I haven't danced in thirty years. I just dare him to try.

The man in charge of the ball-room at No. 177—I shall flatly refuse to call it a yard—said that he didn't believe in any other rule than order, and nearly took my breath away, for just then I had a vision of the club in the doorway; but it was only a vision. The club was not there. As he said it, he mounted the band-stand and waved the crowd to order with his speaking-trumpet.

"A young lady has just lost her gold watch on the floor," he said. "It is here under your feet. Bring it to me, the one who finds it." There was a curious movement of the crowd, as if every unit in it turned once about itself and bowed, and presently a shout of discovery went up. A little girl with a poor shawl pinned about her throat came forward with the watch. The manager waved his trumpet at me with a bright smile.

"You see it works."

The entire crowd fell in behind him in an ecstatic cake-walk, expressive of its joy and satisfaction, and so they went, around and around.

On that very corner, just across the way, a dozen years ago, I gave a stockbroker a good blowing up for hammering his cellar door full of envious nails to prevent the children using it as a slide. It was all the playground they had.

The "Slide" that was the Children's only Playground once.

On the way home I stopped at the first of all the public schools to acquire a roof playground, to see how they did it there. The janitor had been vanquished, but the pedagogue was in charge, and he had organized the life out of it all. The children sat around listless, and made little or no attempt to dance. A harassed teacher was vainly trying to form the girls into ranks for exercises of some kind. They held up their hands in desperate endeavor to get her ear, only to have them struck down impatiently, or to be summarily put out if they tried again. They did not want to exercise. They wanted to play. I tried to voice their grievance to the "doctor" who presided.

"Not at all," he said decisively; "there must be system, system!"

"Tommyrot!" said my Chicago friend at my elbow, and I felt like saying "thank you!" I don't know but I did. They have good sense in Chicago. Jane Addams is there.

The doctor resumed his efforts to teach the boys something, having explained to me that downstairs, where they are when it rains, there were seven distinct echoes to bother the band. Two girls "spieled" in the corner, a kind of dancing that is not favored in the playground. There had been none of that at the other places. The policeman eyed the show with a frown.

So there was a fly in our ointment, after all. But for all that, the janitor is downed, his day dead. This of all things at last has been "settled right," and the path cleared for the children's feet, not in New York only, but everywhere and for all time. I, too, am glad to be alive in the time that saw it done.

CHAPTER XV

"NEIGHBOR" THE PASSWORD

Truly, we live in a wonderful time. Here have I been trying to bring up to date this account of the battle with the slum, and in the doing of it have been compelled, not once, but half a dozen times, to go back and wipe out what I had written because it no longer applied. The ink was not dry on the page that pleaded for the helpless ones who have to leave the hospital before they are fit to take up their battle with the world, so as to make room for others in instant need—one of the saddest of sights that has wrung the heart of the philanthropist these many years—when I read in my paper of the four million dollar gift to build a convalescents' home at once. I would rather be in that man's shoes than be the Czar of all the Russias. I would rather be blessed by the grateful heart of man or woman, who but just now was without hope, than have all the diamonds in the Kimberley mines. Yes, ours is the greatest of all times. Since I started putting these pages in shape for the printer, the Child Labor Committee and the Tuberculosis Committee have been formed to put up bars against the slum where it roamed unrestrained; the Tenement House Department has been organized and got under way, and the knell of the double-decker and the twenty-five-foot lot has been sounded. Two hundred tenements are going up to-day under the new law, that are in all respects model buildings, as good as the City and Suburban Home Company's houses, though built for revenue only. All over the greater city the libraries are rising which, when Mr. Carnegie's munificent plan has been worked out to the full, are to make, with the noble central edifice in Bryant Park, the greatest free library system of any day, with a princely fortune to back it.42 New bridges are spanning our rivers, tunnels are being bored, engineers are blasting a way for the city out of its bonds on crowded Manhattan, devotion and high principle rule once more at the City Hall, Cuba is free, Tammany is out; the boy is coming into his rights; the toughs of Hell's Kitchen have taken to farming on the site of Stryker's Lane, demolished and gone.

And here upon my table lies a letter from the head-worker of the University Settlement, which the postman brought half an hour ago, that lets more daylight in, it seems to me, than all the rest. He has been thinking, he writes, of how to yoke the public school and the social settlement together, and the conviction that comes to everybody who thinks to solve problems, has come to him, too, that the way to do a thing is to do it. So he proposes, since they need another house over at the West Side branch, to acquire it by annexing the public school and turning "all the force and power that is in the branch into the bare walls of the school, there to develop a social spirit and an enthusiasm" among young and old that shall make of the school truly the neighborhood house and soul. And he asks us all to fall in.

I say it lets daylight in, because we have all felt for some time that something like this was bound to come, only how was not clear yet. Here is this immense need of a tenement house population of more than two million souls: something to take the place, as far as anything can, of the home that isn't there, a place to meet other than the saloon; a place for the young to do their courting—there is no room for it in the tenement, and the street is not the place for it, yet it has got to be done; a place to make their elders feel that they are men and women, something else than mere rent-paying units. Why, it was this very need that gave birth to the social settlement among us, and we see now that with the old machinery it does not supply it and never can. "I can reach the people of just about two blocks about me here," said this same head worker of the same settlement to me an evening or two ago, "and that is all." But there are hundreds of blocks filled with hungry minds and souls. A hundred settlements would be needed where there is one.

The churches could not meet the need. They ought to and some day they will, when we build the church down-town and the mission up-town. But now they can't. There are not enough of them, for one thing. They do try; for only the other day, when I went to tell the Methodist ministers of it, and of how they ought to back up the effort to have the public school thrown open on Sundays for concerts, lectures, and the like, after the first shock of surprise they pulled themselves together manfully and said that they would do it. They saw with me that it is a question, not of damaging the Lord's Day, but of wresting it from the devil, who has had it all this while over there on the East Side, and on the West Side too. All along the swarming streets with no church in sight, but a saloon on every corner, stand the big schoolhouses with their spacious halls, empty and silent and grim, waiting to have the soul breathed into them that alone can make their teaching effective for good citizenship. They belong to the people. Why should they not be used by the people Sunday and week-day and day and night, for whatever will serve their ends—if the janitor has a fit?

Now here come the social settlements with their plan of doing it. What claim have they to stand in the gap?

This one, that they are there now, though they do not fill it. The gap has been too much for them. They need the help of those they came to succor quite as much as they need them. I have no desire to find fault with any one who wants to help his neighbor. God forbid! I am not even a settlement worker. But when I read, as I did yesterday, a summing up of the meaning of settlements by three or four residents in such houses, and see education, reform politics, local improvements, legislation, characterized as the aim and objects of settlement work, I am afraid somebody is on the wrong track. Those things are good, provided they spring naturally from the intellectual life that moves in and about the settlement house; indeed, unless they do, something has quite decidedly miscarried there. But they are not the object. When I pick up a report of one settlement and another, and find them filled with little essays on the people and their ways and manners, as if the settlement were same kind of a laboratory where they prepare human specimens for inspection and classification,—stick them on pins like bugs and hold them up and twirl them so as to let us have a good look,—then I know that somebody has wandered away off, and that he knows he has, for all he is making a brave show trying to persuade himself and us that it was worth the money. No use going into that farther. The fact is that we have all been groping. We saw the need and started to fill it, and in the strange surroundings we lost our bearings and the password. We got to be sociological instead of neighborly. It is not the same thing.

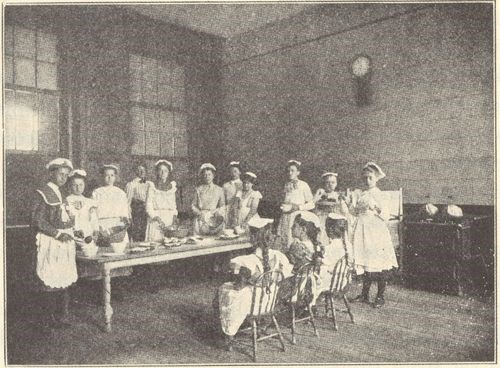

A Cooking Lesson in Vacation School: the Best Temperance Sermon.

Here is the lost password: "neighbor". That is all there is to it. If a settlement isn't the neighbor of those it would reach, it is nothing at all. "A place," said the sub-warden of Toynbee Hall in the discussion I spoke of, and set it on even keel in an instant, "a place of good will rather than of good works." That is it. We had become strangers, had drifted apart, and the settlement came to introduce us to one another again, as it were, to remind us that we were neighbors. And because that was the one thing above all that was wanted, it became an instant success where it was not converted into a social experiment station; and even that could not kill it. If any one doubts that I have the right password, let him look for the proof in the organization this past month of a new "coöperative social settlement," to be carried on "in conjunction and association with the people in the neighborhood." Not a new idea at all, only a fresh grip taken on the old one. It is sound enough and strong enough to set itself right if we will only let it. Only last week Dr. Elliot of the Hudson Guild over in West Twenty-sixth Street told me of his boys' and their fathers' subscribing their savings with the hope of owning the guild house themselves. They had never let go their grip on the idea over there. They are of Felix Adler's flock.

But take now the elements as we have them: this great and terrible longing for neighborliness where the home feeling is gone with the home; the five hundred school buildings in the metropolis that have already successfully been put to neighborhood use. It was nothing else that Dr. Leipziger did when he began his evening lectures in the schools to grown audiences a dozen years ago, and proudly pointed to a record of twenty-two thousand in attendance for the season. Last winter nearly a million workingmen and their wives attended over three thousand lectures.43 Dr. Leipziger is now the strong advocate of opening the schools on the Sabbath, as a kind of Sunday opening we can all join in. Of course he is; he has seen what it means. These factors, the need, the means, and then the settlement that is there to put the two together, as its own great opportunity—has it not a good claim?

Experimenting with the school? Well, what of it? They can stand it. What else have we been doing the last half-dozen years or more, and what splendid results have we not to show for it? It is the spirit that calls every innovation frills, and boasts that we have got the finest schools in the world which blocks the way to progress. It cropped out at a meeting of settlement workers and schoolmen that had for its purpose a better understanding. In the meeting one gray-haired teacher arose and said that the schools as they are were good enough for his father, and therefore they were good enough for him. That teacher's place is on the shelf that has been provided now for those who have done good work in a day that is past. "Vaudeville," sneered the last Tammany mayor, when the East Side asked for a playground for the children. "Vaudeville for the masses killed Rome." The masses responded by killing him politically. My father was a teacher, and it is because he was a good one and taught me that when growth ceases decay begins, that I am never going to be satisfied, no matter how good the schools get to be. I want them ever closer to the people's life, because upon that does that very life depend. Turn back to what I said about the slum tenant and see what it means: in the slum only 4.97 per cent of native parentage. All but five in a hundred had either come over the sea, or else their parents had. Nearly half (46.65) were ignorant, illiterate; for the whole city the percentage of illiteracy was only 7.69. Turn to the reformatory showing: of ten thousand and odd prisoners 66.55 utterly illiterate, or able to read and write only with difficulty. Do you see how the whole battle with the slum is fought out in and around the public school? For in ignorance selfishness finds its opportunity, and the two together make the slum.

The mere teaching is only a part of it. The school itself is a bigger—the meeting there of rich and poor. Out of the public school comes, must come if we are to last, the real democracy that has our hope in keeping. I wish it were in my power to compel every father to send his boy to the public school; I would do it, and so perchance bring the school up to the top notch where it was lacking. The President of the United States to-day sets a splendid example to us all in letting his boys mingle with those who are to be their fellow-citizens by and by. It is precisely in the sundering of our society into classes that have little in common, that are no longer neighbors, that our peril lives. A people cannot work together for the good of the state if they are not on speaking terms. In the gap the slum grows up. That was one reason why I hailed with a shout the proposition of Mr. Schwab, the steel trust millionnaire, to take a regiment of boys down to Staten Island on an excursion every day in summer. Let me see, I haven't told about that, I think. He had bought a large property down there, all beach and lake and field and woodland, and proposed to build a steamer with room for a thousand or two, and then take them down with a band of music on board, and give them a swim, a romp, and a jolly good time. As soon as he spoke to me about it, I said: Yes! and hitch it to the public school somehow; make it part of the curriculum. No more nature study out of a barrel! Take the whole school, teachers and all, and let them do their own gathering of specimens. So the children shall be under efficient control, and so the tired teacher shall get a chance too. But more than all, so it may befall that the boys themselves shall come to know one another better and that more of them shall get together; for what boy does not want a jolly good romp, and why should he not be Mr. Schwab's guest for the day, if he does count his dollars by millions?

The working plan the Board of Education can be trusted to provide. I think it will do it gladly, once it understands. Indeed, why should it not? No one thinks of surrendering the schools, but simply of enlisting the young enthusiasm that is looking for employment, and of a way of turning it to use, while the board is constantly calling for just that priceless personal element which money cannot buy and without which the schools will never reach their highest development. Precedents there are in plenty. If not, we can make them. New York is the metropolis. In Toledo the Park Commissioners take the public school boys sleigh-riding in winter. Our Park Commissioner is ploughing up land for them to learn farming and gardening. It is all experimenting, and let us be glad we have got to that, if we do blunder once and again. The laboratory study, the bug business, we shall get rid of, and we shall get rid of some antediluvian ways that hamper our educational development yet. We shall find a way to make the schools centres of distribution in our library system as its projectors have hoped. Just now it cannot be done, because it takes about a year for a book to pass the ten or twelve different kinds of censorship our sectarian zeal has erected about the school. We shall have the assembly halls thrown open, not only for Dr. Leipziger's lectures and Sunday concerts (already one permit has been granted for the latter), but for trades-union meetings, and for political meetings, if I have my way. Until we consider our politics quite good enough to be made welcome in the school, they won't be good enough for it. The day we do let them in, the saloon will lose its grip, and not much before. When the fathers and mothers meet under the school roof as in their neighborhood house, and the children have their games, their clubs, and their dances there—when the school, in short, takes the place in the life of the people in the crowded quarters which the saloon now monopolizes, there will no longer be a saloon question in politics; and that day the slum is beaten.

Such a Ball-room!

Very likely I shall not find many to agree with me on this question of political meetings. Non-partisan let them be then. So we shall more readily find our way out of the delusion that national politics have any place in municipal elections or affairs, a notion that has delayed the day of decency too long. We shall grow, along with the schools, and by and by our party politics will be clean enough to sit in the school seats too. And oh! by the way, as to those seats, is there any special virtue in the "dead-line" of straight rows that have come down to us from the time of the Egyptians or farther back still? No. I would not lay impious hand on any hallowed tradition, educational or otherwise. But is it that? And why is it? It would be so much easier to make the school the people's hall and the boys' club, if those seats could be moved around in human fashion; they might come naturally into human shape in the doing of it. But, as I said, I wouldn't for the world—not for the world. Only, why is the dead-line hallowed?