полная версия

полная версияThe Battle with the Slum

It is a pity to have to confess it, but it was not the only time reform in office gave its cause a black eye in the sight of the people. The Hamilton Fish Park that took the place of Bone Alley was laid out with such lack of sense that it will have to be worked all over again. The gymnasium and bath in it that cost, I am told, $90,000, was never of any use for either purpose and was never opened. A policeman sat in the door and turned people away, while around the corner clamoring crowds besieged the new public bath I spoke of. There were more people waiting, sitting on the steps and strung out halfway through the block, when I went over to see, one July day, than could have found room in three buildings like it. So, also, after seven years, the promised park down by the Schiff Fountain called Seward Park lies still, an unlovely waste, waiting to be made beautiful. Tammany let its heelers build shanties in it to sell fish and dry-goods and such in. Reform just let things be, no matter how bad they were, and broke its promises to the people.

No, that is not fair. There was enough to do besides, to straighten up things. Tammany had seen to that. This very day34 the contractor's men are beginning work in Seward Park, which shall give that most crowded spot on earth its pleasure-ground, and I have warrant for promising that within a year not only will the "Ham-Fish" Park be restored, but Hudson-bank and the Thomas Jefferson Park in Little Italy, which are still dreary wastes, be opened to the people; while from the Civic Club in Richard Croker's old home ward comes the broad hint that unless condemnation proceedings in the case of the park and playground, to take the place of the old tenements at East Thirty-fifth Street and Second Avenue, are hurried by the Tammany Commission, the club will take a hand and move to have the commission cashiered. There is to be no repetition of the Mulberry Bend scandal.

Kindergarten on the Recreation Pier, at the Foot of E. 24th Street.

It is all right. Neither stupidity, spite, nor coldblooded neglect will be able much longer to cheat the child out of his rights. The playground is here to wrestle with the gang for the boy, and it will win. It came so quietly that we hardly knew of it till we heard the shouts. It took us seven years to make up our minds to build a play pier,—recreation pier is its municipal title,—and it took just about seven weeks to build it when we got so far; but then we learned more in one day than we had dreamed of in the seven years. Half the East Side swarmed over it with shrieks of delight, and carried the mayor and the city government, who had come to see the show, fairly off their feet. And now that pier has more than seven comrades—great, handsome structures, seven hundred feet long, some of them, with music every night for mother and the babies, and for papa, who can smoke his pipe there in peace. The moon shines upon the quiet river, and the steamers go by with their lights. The street is far away with its noise. The young people go sparking in all honor, as it is their right to do. The councilman who spoke of "pernicious influences" lying in wait for them there made the mistake of his life, unless he has made up his mind to go out of politics. That is just a question of effective superintendence, as is true of model tenements, and everything else in this world. You have got to keep the devil out of everything, yourself included. He will get in if he can, as he got into the Garden of Eden. The play piers have taken a hold of the people which no crabbed old bachelor can loosen with trumped-up charges. Their civilizing influence upon the children is already felt in a reported demand for more soap in the neighborhood where they are, and even the grocer smiles approval.

The play pier is the kindergarten in the educational campaign against the gang. It gives the little ones a chance. Often enough it is a chance for life. The street as a playground is a heavy contributor to the undertaker's bank account in more than one way. Distinguished doctors said at the tuberculosis congress this spring that it is to blame with its dust for sowing the seeds of that fatal disease in the half-developed bodies. I kept the police slips of a single day in May two years ago, when four little ones were killed and three crushed under the wheels of trucks in tenement streets. That was unusual, but no day has passed in my recollection that has not had its record of accidents, which bring grief as deep and lasting to the humblest home as if it were the pet of some mansion on Fifth Avenue that was slain. In the Hudson Guild on the West Side they have the reports of ten children that were killed in the street immediately around there. The kindergarten teaching has borne fruit. Private initiative set the pace, but the playground idea has at last been engrafted upon the municipal plan. The Outdoor Recreation League was organized by public-spirited citizens, including many amateur athletes and enthusiastic women, with the object of "obtaining recognition of the necessity for recreation and physical exercise as fundamental to the moral and physical welfare of the people." Together with the School Reform Club and the Federation of Churches and Christian Workers, it maintained a playground on the up-town West Side where the ball came into play for the first time as a recognized factor in civic progress. The day might well be kept for all time among those that mark human emancipation, for it was social reform and Christian work in one, of the kind that tells.

The East River Park.

Only the year before, the athletic clubs had vainly craved the privilege of establishing a gymnasium in the East River Park, where the children wistfully eyed the sacred grass, and cowered under the withering gaze of the policeman. A friend whose house stands opposite the park found them one day swarming over her stoop in such shoals that she could not enter, and asked them why they did not play tag under the trees instead. The instant shout came back, "'Cause the cop won't let us." And now even Poverty Gap is to have its playground—Poverty Gap, that was partly transformed by its one brief season's experience with its Holy Terror Park,35 a dreary sand lot upon the site of the old tenements in which the Alley Gang murdered the one good boy in the block, for the offence of supporting his aged parents by his work as a baker's apprentice. And who knows but the Mulberry Bend and "Paradise Park" at the Five Points may yet know the climbing pole and the vaulting buck. So the world moves. For years the city's only playground that had any claim upon the name—and that was only a little asphalted strip behind a public school in First Street—was an old graveyard. We struggled vainly to get possession of another, long abandoned. But the dead were of more account than the living.

The Seward Park.

But now at last it is their turn. I watched the crowds at their play where Seward Park is to be. The Outdoor Recreation League had put up gymnastic apparatus, and the dusty square was jammed with a mighty multitude. It was not an ideal spot, for it had not rained in weeks, and powdered sand and cinders had taken wing and floated like a pall over the perspiring crowd. But it was heaven to them. A hundred men and boys stood in line, waiting their turn upon the bridge ladder and the travelling rings, that hung full of struggling and squirming humanity, groping madly for the next grip. No failure, no rebuff, discouraged them. Seven boys and girls rode with looks of deep concern—it is their way—upon each end of the seesaw, and two squeezed into each of the forty swings that had room for one, while a hundred counted time and saw that none had too much. It is an article of faith with these children that nothing that is "going" for their benefit is to be missed. Sometimes the result provokes a smile, as when a band of young Jews, starting up a club, called themselves the Christian Heroes. It was meant partly as a compliment, I suppose, to the ladies that gave them club room; but at the same time, if there was anything in a name, they were bound to have it. It is rather to cry over than to laugh at, if one but understands it. The sight of these little ones swarming over a sand heap until scarcely an inch of it was in sight, and gazing in rapt admiration at the poor show of a dozen geraniums and English ivy plants on the window-sill of the overseer's cottage, was pathetic in the extreme. They stood for ten minutes at a time, resting their eyes upon them. In the crowd were aged women and bearded men with the inevitable Sabbath silk hat, who it seemed could never get enough of it. They moved slowly, when crowded out, looking back many times at the enchanted spot, as long as it was in sight.

Perhaps there was in it, on the part of the children at least, just a little bit of the comforting sense of proprietorship. They had contributed of their scant pennies more than a hundred dollars toward the opening of the playground, and they felt that it was their very own. All the better. Two policemen watched the passing show, grinning; their clubs hung idly from their belts. The words of a little woman whom I met once in Chicago kept echoing in my ear. She was the "happiest woman alive," for she had striven long for a playground for her poor children, and had got it.

"The police like it," she said, "They say that it will do more good than all the Sunday-schools in Chicago. The mothers say, 'This is good business.' The carpenters that put up the swings and things worked with a will; everybody was glad. The police lieutenant has had a tree called after him. The boys that did that used to be terrors. Now they take care of the trees. They plead for a low limb that is in the way, that no one may cut it off."

The Seward Park on Opening Day.

The twilight deepens and the gates of the playground are closed. The crowds disperse slowly. In the roof garden on the Hebrew Institute across East Broadway lights are twinkling and the band is tuning up. Little groups are settling down to a quiet game of checkers or love-making. Paterfamilias leans back against the parapet where palms wave luxuriously in the summer breeze. The newspaper drops from his hand; he closes his eyes and is in dreamland, where strikes come not. Mother knits contentedly in her seat, with a smile on her face that was not born of the Ludlow Street tenement. Over yonder a knot of black-browed men talk with serious mien. They might be met any night in the anarchist café, half a dozen doors away, holding forth against empires. Here wealth does not excite their wrath, nor power their plotting. In the roof garden anarchy is harmless, even though a policeman typifies its government. They laugh pleasantly to one another as he passes, and he gives them a match to light their cigars. It is Thursday, and smoking is permitted. On Friday it is discouraged because it offends the orthodox, to whom the lighting of a fire, even the holding of a candle, is anathema on the Sabbath eve.

In the Roof Garden of the Hebrew Educational Alliance.

The band plays on. One after another, tired heads droop upon babes slumbering peacefully at the breast. Ludlow Street—the tenement—are forgotten; eleven o'clock is not yet. Down along the silver gleam of the river a mighty city slumbers. The great bridge has hung out its string of shining pearls from shore to shore. "Sweet land of liberty!" Overhead the dark sky, the stars that twinkled their message to the shepherds on Judæan hills, that lighted their sons through ages of slavery, and the flag of freedom borne upon the breeze,—down there the tenement, the—Ah, well! let us forget as do these.

Bottle Alley, Whyó Gang's Headquarters.

This picture was evidence at a murder trial. The X marks the place where the murderer stood when he shot his victim on the stairs.

Now if you ask me: "And what of it all? What does it avail?" let me take you once more back to the Mulberry Bend, and to the policeman's verdict add the police reporter's story of what has taken place there. In fifteen years I never knew a week to pass without a murder there, rarely a Sunday. It was the wickedest, as it was the foulest, spot in all the city. In the slum the two are interchangeable terms for reasons that are clear enough for me. But I shall not speculate about it, only state the facts. The old houses fairly reeked with outrage and violence. When they were torn down, I counted seventeen deeds of blood in that place which I myself remembered, and those I had forgotten probably numbered seven times seventeen. The district attorney connected more than a score of murders of his own recollection with Bottle Alley, the Whyó Gang's headquarters. Five years have passed since it was made into a park, and scarce a knife had been drawn or a shot fired in all that neighborhood. Only twice have I been called as a police reporter to the spot. It is not that the murder has moved to another neighborhood, for there has been no increase of violence in Little Italy or wherever else the crowd went that moved out. It is that the light has come in and made crime hideous. It is being let in wherever the slum has bred murder and robbery, bred the gang, in the past. Wait, now, another ten years, and let us see what a story there will be to tell.

Avail? Why, it was only the other day that Tammany was actually caught applauding36 Comptroller Coler's words in Plymouth Church, "Whenever the city builds a schoolhouse upon the site of a dive and creates a park, a distinct and permanent mental, moral, and physical improvement has been made, and public opinion will sustain such a policy, even if a dive-keeper is driven out of business and somebody's ground rent is reduced." And Tammany's press agent, in his enthusiasm, sent forth this pæan: "In the light of such events how absurd it is for the enemies of the organization to contend that Tammany is not the greatest moral force in the community." Tammany a moral force! The park and the playground have availed, then, to bring back the day of miracles.

CHAPTER XII

THE PASSING OF CAT ALLEY

When Santa Claus comes around to New York this Christmas he will look in vain for some of the slum alleys he used to know. They are gone. Where some of them were, there are shrubs and trees and greensward; the sites of others are holes and hillocks yet, that by and by, when all the official red tape is unwound,—and what a lot of it there is to plague mankind!—will be levelled out and made into playgrounds for little feet that have been aching for them too long. Perhaps it will surprise some good people to hear that Santa Claus knew the old alleys; but he did. I have been there with him, and I knew that, much as some things which he saw there grieved him,—the starved childhood, the pinching poverty, and the slovenly indifference that cut deeper than the rest because it spoke of hope that was dead,—yet by nothing was his gentle spirit so grieved and shocked as by the show that proposed to turn his holiday into a battalion drill of the children from the alleys and the courts for patricians, young and old, to review. It was well meant, but it was not Christmas. That belongs to the home, and in the darkest slums Santa Claus found homes where his blessed tree took root and shed its mild radiance about, dispelling the darkness, and bringing back hope and courage and trust.

They are gone, the old alleys. Reform wiped them out. It is well. Santa Claus will not have harder work finding the doors that opened to him gladly, because the light has been let in. And others will stand ajar that before were closed. The chimneys in tenement-house alleys were never built on a plan generous enough to let him in in the orthodox way. The cost of coal had to be considered in putting them up. Bottle Alley and Bandits' Roost are gone with their bad memories. Bone Alley is gone, and Gotham Court. I well remember the Christmas tree in the court, under which a hundred dolls stood in line, craving partners among the girls in its tenements. That was the kind of battalion drill that they understood. The ceiling of the room was so low that the tree had to be cut almost in half; but it was beautiful, and it lives yet, I know, in the hearts of the little ones, as it lives in mine. The "Barracks" are gone, Nibsey's Alley is gone, where the first Christmas tree was lighted the night poor Nibsey lay dead in his coffin. And Cat Alley is gone.

The First Christmas Tree in Gotham Court.

Cat Alley was my alley. It was mine by right of long acquaintance. We were neighbors for twenty years. Yet I never knew why it was called Cat Alley. There was the usual number of cats, gaunt and voracious, which foraged in its ash-barrels; but beyond the family of three-legged cats, that presented its own problem of heredity,—the kittens took it from the mother, who had lost one leg under the wheels of a dray,—there was nothing specially remarkable about them. It was not an alley, either, when it comes to that, but rather a row of four on five old tenements in a back yard that was reached by a passageway somewhat less than three feet wide between the sheer walls of the front houses. These had once had pretensions to some style. One of them had been the parsonage of the church next door that had by turns been an old-style Methodist tabernacle, a fashionable negroes' temple, and an Italian mission church, thus marking time, as it were, to the upward movement of the immigration that came in at the bottom, down in the Fourth Ward, fought its way through the Bloody Sixth, and by the time it had travelled the length of Mulberry Street had acquired a local standing and the right to be counted and rounded up by the political bosses. Now the old houses were filled with newspaper offices and given over to perpetual insomnia. Week-days and Sundays, night or day, they never slept. Police headquarters was right across the way, and kept the reporters awake. From his window the chief looked down the narrow passageway to the bottom of the alley, and the alley looked back at him, nothing daunted. No man is a hero to his valet, and the chief was not an autocrat to Cat Alley. It knew all his human weaknesses, could tell when his time was up generally before he could, and winked the other eye with the captains when the newspapers spoke of his having read them a severe lecture on gambling or Sunday beer-selling. Byrnes it worshipped, but for the others who were before him and followed after, it cherished a neighborly sort of contempt.

In the character of its population Cat Alley was properly cosmopolitan. The only element that was missing was the native American, and in this it was representative of the tenement districts in America's chief city. The substratum was Irish, of volcanic properties. Upon this were imposed layers of German, French, Jewish, and Italian, or, as the alley would have put it, Dutch, Sabé, Sheeny, and Dago; but to this last it did not take kindly. With the experience of the rest of Mulberry Street before it, it foresaw its doom if the Dago got a footing there, and within a month of the moving in of the Gio family there was an eruption of the basement volcano, reënforced by the sanitary policeman, to whom complaint had been made that there were too many "Ginnies" in the Gio flat. There were four—about half as many as there were in some of the other flats when the item of house rent was lessened for economic reasons; but it covered the ground: the flat was too small for the Gios. The appeal of the signora was unavailing. "You got-a three bambino," she said to the housekeeper, "all four, lika me," counting the number on her fingers. "I no putta me broder-in-law and me sister in the street-a. Italian lika to be together."

The housekeeper was unmoved. "Humph!" she said, "to liken my kids to them Dagos! Out they go." And they went.

Up on the third floor there was the French couple. It was another of the contradictions of the alley that of this pair the man should have been a typical, stolid German, she a mercurial Parisian, who at seventy sang the "Marseillaise" with all the spirit of the Commune in her cracked voice, and hated from the bottom of her patriotic soul the enemy with whom the irony of fate had yoked her. However, she improved the opportunity in truly French fashion. He was rheumatic, and most of the time was tied to his chair. He had not worked for seven years. "He no goode," she said, with a grimace, as her nimble fingers fashioned the wares by the sale of which, from a basket, she supported them both. The wares were dancing girls with tremendous limbs and very brief skirts of tricolor gauze,—"ballerinas," in her vocabulary,—and monkeys with tin hats, cunningly made to look like German soldiers. For these she taught him to supply the decorations. It was his department, she reasoned; the ballerinas were of her country and hers. Parbleu! must one not work? What then? Starve? Before her look and gesture the cripple quailed, and twisted and rolled and pasted all day long, to his country's shame, fuming with impotent rage.

"I wish the devil had you," he growled.

She regarded him maliciously, with head tilted on one side, as a bird eyes a caterpillar it has speared.

"Hein!" she scoffed. "Du den, vat?"

He scowled. She was right; without her he was helpless. The judgment of the alley was unimpeachable. They were and remained "the French couple."

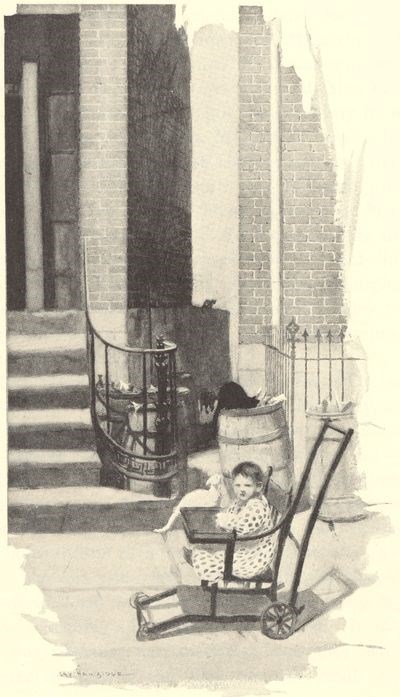

The Mouth of the Alley.

By permission of the Century Company.

Cat Alley's reception of Madame Klotz at first was not cordial. It was disposed to regard as a hostile act the circumstance that she kept a special holiday, of which nothing was known except from her statement that it referred to the fall of somebody or other whom she called the Bastille, in suspicious proximity to the detested battle of the Boyne; but when it was observed that she did nothing worse than dance upon the flags "avec ze leetle bébé" of the tenant in the basement, and torture her "Dootch" husband with extra monkeys and gibes in honor of the day, unfavorable judgment was suspended, and it was agreed that without a doubt the "bastard" fell for cause; wherein the alley showed its sound historical judgment. By such moral pressure when it could, by force when it must, the original Irish stock preserved the alley for its own quarrels, free from "foreign" embroilments. These quarrels were many and involved. When Mrs. M'Carthy was to be dispossessed, and insisted, in her cups, on killing the housekeeper as a necessary preliminary, a study of the causes that led to the feud developed the following normal condition: Mrs. M'Carthy had the housekeeper's place when Mrs. Gehegan was poor, and fed her "kids." As a reward, Mrs. Gehegan worked around and got the job away from her. Now that it was Mrs. M'Carthy's turn to be poor, Mrs. Gehegan insisted upon putting her out. Whereat, with righteous wrath, Mrs. M'Carthy proclaimed from the stoop: "Many is the time Mrs. Gehegan had a load on, an' she went upstairs an' slept it off. I didn't. I used to show meself, I did, as a lady. I know ye're in there, Mrs. Gehegan. Come out an' show yerself, an' I'ave the alley to judge betwixt us." To which Mrs. Gehegan prudently vouchsafed no answer.

Mrs. M'Carthy had succeeded to the office of housekeeper upon the death of Miss Mahoney, an ancient spinster who had collected the rents since the days of "the riot," meaning the Orange riot—an event from which the alley reckoned its time, as the ancients did from the Olympian games. Miss Mahoney was a most exemplary and worthy old lady, thrifty to a fault. Indeed, it was said when she was gone that she had literally starved herself to death to lay by money for the rainy day she was keeping a lookout for to the last. In this she was obeying her instincts; but they went counter to those of the alley, and the result was very bad. As an example, Miss Mahoney's life was a failure. When at her death it was discovered that she had bank-books representing a total of two thousand dollars, her nephew and only heir promptly knocked off work and proceeded to celebrate, which he did with such fervor that in two months he had run through it all and killed himself by his excesses. Miss Mahoney's was the first bank account in the alley, and, so far as I know, the last.