полная версия

полная версияStory of the Bible Animals

Plentiful as is the Frog throughout Egypt, Palestine, and Syria, it is very remarkable that in the whole of the canonical books of the Old Testament the word is only mentioned thrice, and each case in connexion with the same event.

In Exod. viii. we find that the second of the plagues which visited Egypt came out of the Nile, the sacred river, in the form of innumerable Frogs. The reader will probably remark, on perusing the consecutive account of these plagues, that the two first plagues were connected with that river, and that they were foreshadowed by the transformation of Aaron's rod.

When Moses and Aaron appeared before Pharaoh to ask him to let the people go, Pharaoh demanded a miracle from them, as had been foretold. Following the divine command, Aaron threw down his rod, which was changed into a serpent.

Next, as was most appropriate, came a transformation wrought on the river by means of the same rod which had been transformed into a Serpent, the whole of the fresh-water throughout the land being turned into blood, and the fish dying and polluting the venerated river with their putrefying bodies. In Egypt, a partially rainless country, such a calamity as this was doubly terrible, as it at the same time desecrated the object of their worship, and menaced them with perishing by thirst.

The next plague had also its origin in the river, but extended far beyond the limits of its banks. The frogs, being unable to return to the contaminated stream wherein they had lived, spread themselves in all directions, so as to fulfil the words of the prediction: "If thou refuse to let them go, behold, I will smite all thy borders with frogs:

"And the river shall bring forth frogs abundantly, which shall go up and come into thine house, and into thy bed-chamber, and upon thy bed, and into the house of thy servants, and upon thy people, and into thine ovens, and into thy kneading-troughs" (or dough).

Supposing that such a plague was to come upon us at the present day, we should consider it to be a terrible annoyance, yet scarcely worthy of the name of plague, and certainly not to be classed with the turning of a river into blood, with the hail and lightning that destroyed the crops and cattle, and with the simultaneous death of the first-born. But the Egyptians suffered most keenly from the infliction. They were a singularly fastidious people, and abhorred the contact of anything that they held to be unclean. We may well realize, therefore, the effect of a visitation of Frogs, which rendered their houses unclean by entering them, and themselves unclean by leaping upon them; which deprived them of rest by getting on their beds, and of food by crawling into their ovens and upon the dough in the kneading-troughs.

And, as if to make the visitation still worse, when the plague was removed, the Frogs died in the places into which they had intruded, so that the Egyptians were obliged to clear their houses of the dead carcases, and to pile them up in heaps, to be dried by the sun or eaten by birds and other scavengers of the East.

As to the species of Frog which thus invaded the houses of the Egyptians, there is no doubt whatever. It can be but the Green, or Edible Frog (Rana esculenta), which is so well known for the delicacy of its flesh. This is believed to be the only aquatic Frog of Egypt, and therefore must be the species which came out of the river into the houses.

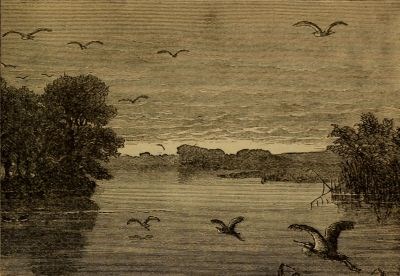

Both in Egypt and Palestine it exists in very great numbers, swarming in every marshy place, and inhabiting the pools in such numbers that the water can scarcely be seen for the Frogs. Thus the multitudes of the Frogs which invaded the Egyptians was no matter of wonder, the only miraculous element being that the reptiles were simultaneously directed to the houses, and their simultaneous death when the plague was taken away.

Frogs are also mentioned in Rev. xvi. 13: "And I saw three unclean spirits like frogs come out of the mouth of the dragon, and out of the mouth of the beast, and out of the mouth of the false prophet." With the exception of this passage, which is a purely symbolical one, there is no mention of Frogs in the New Testament. It is rather remarkable that the Toad, which might be thought to afford an excellent symbol for various forms of evil, is entirely ignored, both in the Old and New Testaments. Probably the Frogs and Toads were all classed together under the same title.

FISHES

Impossibility of distinguishing the different species of Fishes—The fishermen Apostles—Fish used for food—The miracle of the loaves and Fishes—The Fish broiled on the coals—Clean and unclean Fishes—The Sheat-fish, or Silurus—The Eel and the Muræna—The Long-headed Barbel—Fish-ponds and preserves—The Fish-ponds of Heshbon—The Sucking-fish—The Lump-sucker—The Tunny—The Coryphene.

We now come to the Fishes, a class of animals which are repeatedly mentioned both in the Old and New Testaments, but only in general terms, no one species being described so as to give the slightest indication of its identity.

This is the more remarkable because, although the Jews were, like all Orientals, utterly unobservant of those characteristics by which the various species are distinguished from each other, we might expect that St. Peter and other of the fisher Apostles would have given the names of some of the Fish which they were in the habit of catching, and by the sale of which they gained their living.

It is true that the Jews, as a nation, would not distinguish between the various species of Fishes, except, perhaps, by comparative size. But professional fishermen would be sure to distinguish one species from another, if only for the fact that they would sell the best-flavoured Fish at the highest price.

We might have expected, for example, that the Apostles and disciples who were present when the miraculous draught of Fishes took place would have mentioned the technical names by which they were accustomed to distinguish the different degrees of the saleable and unsaleable kinds.

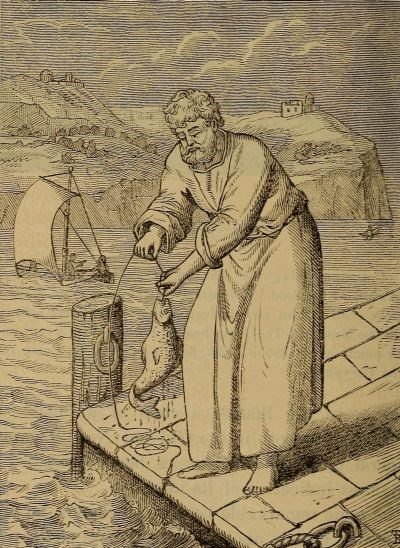

PETER CATCHES THE FISH.

Or we might have expected that on the occasion when St. Peter cast his line and hook into the sea, and drew out a Fish holding the tribute-money in his mouth, we might have learned the particular species of Fish which was thus captured. We ourselves would assuredly have done so. It would not have been thought sufficient merely to say that a Fish was caught with money in its mouth, but it would have been considered necessary to mention the particular fish as well as the particular coin.

But it must be remembered that the whole tone of thought differs in Orientals and Europeans, and that the exactness required by the one has no place in the mind of the other. The whole of the Scriptural narratives are essentially Oriental in their character, bringing out the salient points in strong relief, but entirely regardless of minute detail.

We find from many passages both in the Old and New Testaments that Fish were largely used as food by the Israelites, both when captives in Egypt and after their arrival in the Promised Land. Take, for example, Numb. xi. 4, 5: "And the children of Israel also wept again, and said, Who shall give us flesh to eat?

"We remember the fish which we did eat in Egypt freely." Then, in the Old Testament, although we do not find many such categorical statements, there are many passages which allude to professional fishermen, showing that there was a demand for the Fish which they caught, sufficient to yield them a maintenance.

In the New Testament, however, there are several passages in which the Fishes are distinctly mentioned as articles of food. Take, for example, the well-known miracle of multiplying the loaves and the Fishes, and the scarcely less familiar passage in John xxi. 9: "As soon then as they were come to land, they saw a fire of coals there, and fish laid thereon, and bread."

We find in all these examples that bread and Fish were eaten together. Indeed, Fish was eaten with bread just as we eat cheese or butter; and St. John, in his account of the multiplication of the loaves and Fishes, does not use the word "fish," but another word which rather signifies sauce, and was generally employed to designate the little Fish that were salted down and dried in the sunbeams for future use.

As to the various species which were used for different purposes, we know really nothing, the Jews merely dividing their Fish into clean and unclean.

Some of the species to which the prohibition would extend are evident enough. There are, for example, the Sheat-fishes, which have the body naked, and which are therefore taken out of the list of permitted Fishes. The Sheat-fishes inhabit rivers in many parts of the world, and often grow to a very considerable size. They may be at once recognised by their peculiar shape, and by the long, fleshy tentacles that hang from the mouth. The object of these tentacles is rather dubious, but as the fish have been seen to direct them at will to various objects, it is likely that they may answer as organs of touch.

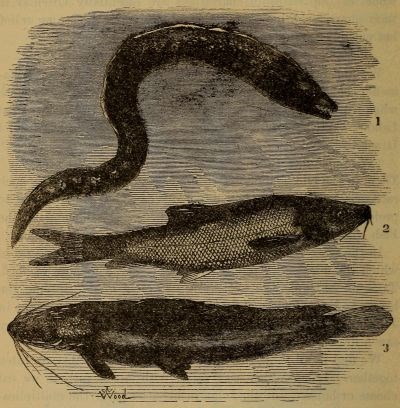

1. Muræna. 2. Long-headed barbel. 3. Sheat-fish.

As might be conjectured from its general appearance, it is one of the Fishes that love muddy banks, in which it is fond of burrowing so deeply that, although the river may swarm with Sheat-fishes, a practised eye is required to see them.

As far as the Sheat-fishes are concerned, there is little need for the prohibition, inasmuch as the flesh is not at all agreeable in flavour, and is difficult of digestion, being very fat and gelatinous. The swimming-bladder of the Sheat-fish is used in some countries for making a kind of isinglass, similar in character to that of the sturgeon, but of coarser quality.

The lowermost figure in the above illustration represents a species which is exceedingly plentiful in the Sea of Galilee.

On account of the mode in which their body is covered, the whole of the sharks and rays are excluded from the list of permitted Fish, as, although they have fins, they have no scales, their place being taken by shields varying greatly in size. The same rule excludes the whole of the lamprey tribe, although the excellence of their flesh is well known.

Moreover, the Jews almost universally declare that the Muræna and Eel tribe are also unclean, because, although it has been proved that these Fishes really possess scales as well as fins, and are therefore legally permissible, the scales are hidden under a slimy covering, and are so minute as to be practically absent.

The uppermost figure in the illustration represents the celebrated Muræna, one of the fishes of the Mediterranean, in which sea it is tolerably plentiful. In the days of the old Roman empire, the Muræna was very highly valued for the table. The wealthier citizens built ponds in which the Murænæ were kept alive until they were wanted. This Fish sometimes reaches four feet in length.

The rest of the Fishes which are shown in the three illustrations belong to the class of clean Fish, and were permitted as food. The figure of the Fish between the Muræna and Sheat-fish is the Long-headed Barbel, so called from its curious form.

The Barbels are closely allied to the carps, and are easily known by the barbs or beards which hang from their lips. Like the sheat-fishes, the Barbels are fond of grubbing in the mud, for the purpose of getting at the worms, grubs, and larvæ of aquatic insects that are always to be found in such places. The Barbels are rather long in proportion to their depth, a peculiarity which, owing to the length of the head, is rather exaggerated in this species.

The Long-headed Barbel is extremely common in Palestine, and may be taken with the very simplest kind of net. Indeed, in some places, the fish are so numerous that a common sack answers nearly as well as a net.

It has been mentioned that the ancient Romans were in the habit of forming ponds in which the Murænæ were kept, and it is evident, from several passages of Scripture, that the Jews were accustomed to preserve fish in a similar manner, though they would not restrict their tanks or ponds to one species.

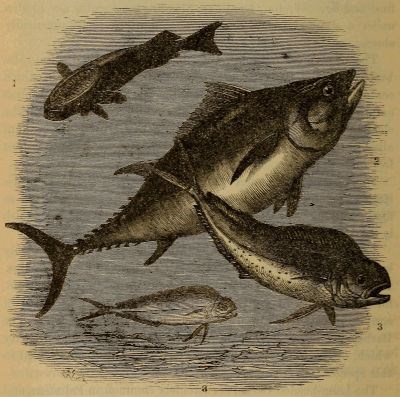

The accompanying illustration represents Fishes of the Mediterranean Sea, and it is probable that one of them may be identified, though the passage in which it is mentioned is only an inferential one. In the prophecy against Pharaoh, king of Egypt, the prophet Ezekiel writes as follows: "I will put hooks in thy jaws, and I will cause the fish of thy rivers to stick unto thy scales, and I will bring thee up out of the midst of thy rivers, and all the fish of thy rivers shall stick unto thy scales" (xxix. 4).

FISHES OF THE MEDITERRANEAN.

1. Sucking-fish. 2. Tunny. 3. Coryphene.

Some believe that the prophet made allusion to the Sucking-fish, which has the dorsal fins developed into a most curious apparatus of adhesion, by means of which it can fasten itself at will to any smooth object, and hold so tightly to it that it can scarcely be torn away without injury.

The common Sucking-fish is shown in the upper part of the illustration.

There are, however, other fish which have powers of adhesion which, although not so remarkable as those of the Sucking-fish, are yet very strong. There is, for example, the well-known Lump-sucker, or Lump-fish, which has the ventral fins modified into a sucker so powerful that, when one of these fishes has been put into a pail of water, it has attached itself so firmly to the bottom of the vessel that when lifted by the tail it raised the pail, together with several gallons of water.

The Gobies, again, have their ventral fins united and modified into a single sucker, by means of which the fish is able to secure itself to a stone, rock, or indeed any tolerably smooth surface. These fishes are popularly known as Bull-routs.

The centre of the illustration is occupied by another of the Mediterranean fishes. This is the well-known Tunny, which furnishes food to the inhabitants of the coasts of this inland sea, and indeed constitutes one of their principal sources of wealth. This fine fish is on an average four or five feet in length, and sometimes attains the length of six or seven feet.

The flesh of the Tunny is excellent, and the fish is so conspicuous, that the silence of the Scriptures concerning its existence shows the utter indifference to specific accuracy that prevailed among the various writers.

The other figure represents the Coryphene, popularly, though very wrongly, called the Dolphin, and celebrated, under that name, for the beautiful colours which fly over the surface of the body as it dies.

The flesh of the Coryphene is excellent, and in the times of classic Rome the epicures were accustomed to keep these fish alive, and at the beginning of a feast to lay them before the guests, so that they might, in the first place, witness the magnificent colours of the dying fish, and, in the second place, might be assured that when it was cooked it was perfectly fresh. Even during life, the Coryphene is a most lovely fish, and those who have witnessed it playing round a ship, or dashing off in chase of a shoal of flying-fishes, can scarcely find words to express their admiration of its beauty.

FISHES

CHAPTER II

Various modes of capturing Fish—The hook and line—Military use of the hook—Putting a hook in the jaws—The fishing spear—Different kinds of net—The casting-net—Prevalence of this form—Technical words among fishermen—Fishing by night—The draught of Fishes—The real force of the miracle—Selecting the Fish—The Fish-gate and Fish-market—Fish killed by a draught—Fishing in the Dead Sea—Dagon, the fish-god of Philistina, Assyria, and Siam—Various Fishes of Egypt and Palestine.

As to the various methods of capturing Fish, we will first take the simplest plan, that of the hook and line.

Sundry references are made to angling, both in the Old and New Testaments. See, for example, the well-known passage respecting the leviathan, in Job xli. 1, 2: "Canst thou draw out leviathan with an hook? or his tongue with a cord which thou lettest down?

"Canst thou put an hook into his nose? or bore his jaw through with a thorn?"

It is thought that the last clause of this passage refers, not to the actual capture of the Fish, but to the mode in which they were kept in the tanks, each being secured by a ring or hook and line, so that it might be taken when wanted.

On referring to the New Testament, we find that the fisher Apostles used both the hook and the net. See Matt. xvii. 27: "Go thou to the sea, and cast an hook, and take up the fish that first cometh up." Now this passage explains one or two points.

In the first place, it is one among others which shows that, although the Apostles gave up all to follow Christ, they did not throw away their means of livelihood, as some seem to fancy, nor exist ever afterwards on the earnings of others. On the contrary, they retained their fisher equipment, whether boats, nets, or hooks; and here we find St. Peter, after the way of fishermen, carrying about with him the more portable implements of his craft.

Next, the phrase "casting" the hook into the sea is exactly expressive of the mode in which angling is conducted in the sea and large pieces of water, such as the Lake of Galilee. The fisherman does not require a rod, but takes his line, which has a weight just above the hook, coils it on his left arm in lasso fashion, baits the hook, and then, with a peculiar swing, throws it into the water as far as it will reach. The hook is allowed to sink for a short time, and is then drawn towards the shore in a series of jerks, in order to attract the Fish, so that, although the fisherman does not employ a rod, he manages his line very much as does an angler of our own day when "spinning" for pike or trout.

Sometimes the fisherman has a number of lines to manage, and in this case he acts in a slightly different manner. After throwing out the loaded hook, as above mentioned, he takes a short stick, notched at one end, and pointed at the other, thrusts the sharp end into the ground at the margin of the water, and hitches the line on the notch.

He then proceeds to do the same with all his lines in succession, and when he has flung the last hook into the water, he sits down on a heap of leaves and grass which he has gathered together, and watches the lines to see if either of them is moved in the peculiar jerking manner which is characteristic of a "bite." After a while, he hauls them in successively, removes the Fish that may have been caught, and throws the lines into the water afresh.

We now come to the practice of catching Fish by the net, a custom to which the various Scriptural writers frequently refer, sometimes in course of historical narrative, and sometimes by way of allegory or metaphor. The reader will remember that the net was also used on land for the purpose of catching wild animals, and that many of the allusions to the net which occur in the Old Testament refer to the land and not to the water.

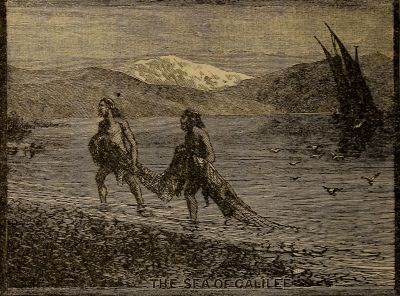

The commonest kind of net, which was used in the olden times as it is now, was the casting-net. This kind of net is circular, and is loaded all round its edge with weights, and suspended by the middle to a cord. When the fisherman throws this net, he gathers it up in folds in his arms, and, with a peculiar swing of the arms, only to be learned by long practice, flings it so that it spreads out and falls in its circular form upon the surface of the water. It rapidly sinks to the bottom, the loaded circumference causing it to assume a cup-like form, enclosing within its meshes all the Fish that happen to be under it as it falls. When it has reached the bottom, the fisherman cautiously hauls in the rope, so that the loaded edges gradually approach each other, and by their own weight cling together and prevent the Fish from escaping as the net is slowly drawn ashore.

This kind of net is found, with certain modifications, in nearly all parts of the world. The Chinese are perhaps supreme in their management of it. They have a net of extraordinary size, and cast it by flinging it over their backs, the huge circle spreading itself out in the most perfect manner as it falls on the water.

At the present day, when the fishermen use this net they wade into the sea as far as they can, and then cast it. In consequence of this custom, the fishermen are always naked while engaged in their work, wearing nothing but a thick cap in order to save themselves from sun-stroke. It is probable that on the memorable occasion mentioned by St. John, in chap. xxi., all the fishermen were absolutely, and not relatively naked, wearing no clothes at all, not even the ordinary tunic.

That a great variety of nets was used by the ancient Jews is evident from the fact that there are no less than ten words to signify different kinds of net. At the present day we have very great difficulty in deciding upon the exact interpretation of these technical terms, especially as in very few cases are we assisted either by the context or by the etymology of the words. It is the same in all trades or pursuits, and we can easily understand how our own names of drag-net, seine, trawl, and keer-drag would perplex any commentator who happened to live some two thousand years after English had ceased to be a living language.

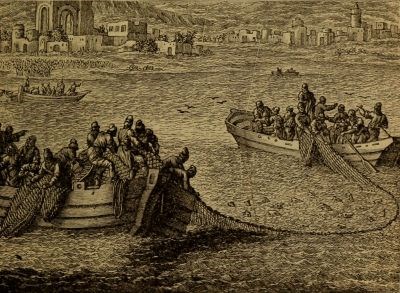

MODE OF DRAGGING THE SEINE-NET.

The Sagene, or seine-net, was made in lengths, any number of which could be joined together, so as to enclose a large space of water. The upper edge was kept at the surface of the water by floats, and the lower edge sunk by weights.

This net was always taken to sea in vessels, and when "shot" the various lengths were joined together, and the net extended in a line, with a boat at each end. The boats then gradually approached each other, so as to bring the net into a semicircle, and finally met, enclosing thereby a vast number of Fishes in their meshen walls. The water was then beaten, so as to frighten the Fishes and drive them into the meshes, and the net was then either taken ashore, or lifted by degrees on board the boats, and the Fish removed from it.

As in a net of this kind Fishes of all sorts are enclosed, the contents are carefully examined, and those which are unfit for eating are thrown away. Even at the present day much care is taken in the selection, but in the ancient times the fishermen were still more cautious, every Fish having to be separately examined in order that the presence both of fins and scales might be assured before the captors could send it to the market.

It is to this custom that Christ alludes in the well-known parable of the net: "Again, the kingdom of heaven is like unto a net that was cast into the sea, and gathered of every kind;

"Which, when it was full, they drew to shore, and sat down, and gathered the good into vessels, but cast the bad away."

Lastly, we come to the religious, or rather superstitious, part played by Fish in the ancient times. That the Egyptians employed Fish as material symbols of Divine attributes we learn from secular writers, such as Herodotus and Strabo.

The Jews, who seem to have had an irrepressible tendency to idolatry, and to have adopted the idols of every people with whom they came in contact, resuscitated the Fish-worship of Egypt as soon as they found themselves among the Philistines. We might naturally imagine that as the Israelites were bitterly opposed to their persistent enemy, who trod them under foot and crushed every attempt at rebellion for more than three hundred years, they would repudiate the worship as well as the rule of their conquerors. But, on the contrary, they adopted the worship of Dagon, the Fish-god, who was the principal deity of the Philistines, and erected temples in his honour.